George Cruikshank stands as one of the most prolific, influential, and instantly recognizable figures in the history of British illustration and caricature. Spanning a career that lasted over seven decades, from the Regency period well into the high Victorian era, Cruikshank produced an astonishing volume of work, ranging from biting political satire to detailed book illustrations and powerful social commentary. His unique style, energetic line, and keen observation of human nature earned him immense popularity and the enduring title of the "modern Hogarth." Born into an artistic family, he not only inherited a talent for drawing but also shaped the visual culture of his time, leaving an indelible mark on literature, social reform movements, and the art of graphic satire itself.

Early Life and Artistic Inheritance

George Cruikshank was born in London on September 27, 1792. He entered a world brimming with political upheaval and social change, fertile ground for the satirical arts. His father, Isaac Cruikshank (c. 1764–1811), was a respected and successful caricaturist and etcher of Scottish descent, known for his own sharp political commentary, particularly during the turbulent years of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. George, along with his elder brother, Isaac Robert Cruikshank (1789–1856), who also became a notable artist specializing in caricature and illustration, grew up immersed in the craft.

From a very young age, George was apprenticed, albeit informally, in his father's workshop. He learned the demanding techniques of drawing, etching, and watercolour painting directly from Isaac. The environment was one of constant production, responding rapidly to political events and social trends with prints that were sold widely on the streets and in print shops. This early exposure instilled in George not only technical skill but also a remarkable speed and facility, as well as an understanding of the public appetite for graphic satire.

Following his father's untimely death in 1811, the young George, not yet twenty, stepped up to help support his family through his art. He quickly began to make a name for himself, initially sometimes even completing his father's unfinished plates or working in a style very close to his. However, he soon developed his own distinctive voice and graphic style, one characterized by wiry, energetic lines, exaggerated physiognomies, and a crowded, detailed composition that captured the teeming life of London.

The Rise of a Satirical Star

The Regency period (1811-1820) and the subsequent decades saw George Cruikshank emerge as a leading force in British caricature, inheriting the mantle from the previous generation's giants like James Gillray (1756-1815) and Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827). While Gillray was known for his savage political attacks and Rowlandson for his robust, often bawdy, depictions of social life, Cruikshank carved his own niche. His work often blended political critique with sharp observations of social manners, fashion, and the everyday absurdities of urban existence.

He fearlessly lampooned prominent figures, including Napoleon Bonaparte, whom he depicted with particular relish during the ongoing wars, often portraying him as the diminutive "Little Boney." The British monarchy was another frequent target. He satirized the Prince Regent (later King George IV), mocking his extravagance, vanity, and scandals. A famous anecdote illustrates his boldness: it's said that he was offered a bribe of £100 to refrain from caricaturing the King in any "immoral situation." Cruikshank reportedly agreed, stating he would depict the monarch morally, but cleverly implied this was hardly a limitation given the King's reputation.

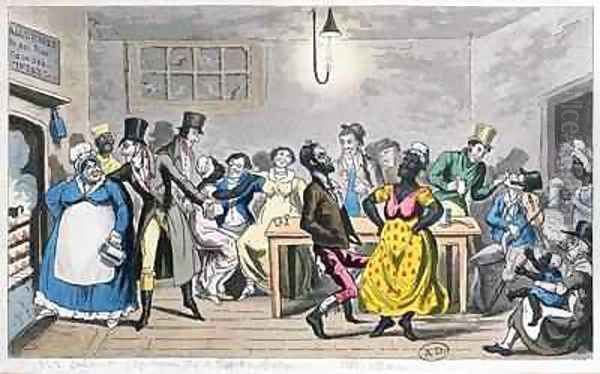

Beyond high politics, Cruikshank excelled at capturing the social landscape. His collaborations, such as Pierce Egan's Life in London (1821), illustrated jointly with his brother Robert, were immensely popular. These works followed the adventures of Tom, Jerry, and Logic through various strata of London society, from high-life salons to low-life taverns and sporting events, providing a vibrant, albeit often romanticized, panorama of the metropolis. Cruikshank's detailed and lively illustrations were crucial to the success of such publications.

Illustrator of Literature: The Dickens Connection

While Cruikshank achieved fame through his satirical prints, his transition into book illustration cemented his legacy and brought his work to an even wider audience. His most celebrated collaboration was undoubtedly with the young Charles Dickens. Cruikshank provided the illustrations for Dickens's early success, Sketches by Boz (1836), capturing the energy and eccentricity of London life that Dickens described in prose.

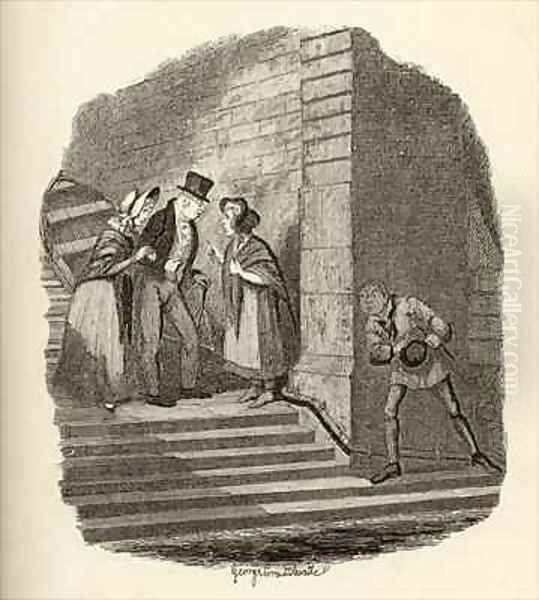

This partnership reached its zenith with Oliver Twist (published serially 1837-1839). Cruikshank's etchings for this novel are among the most iconic literary illustrations ever produced. His depictions of Fagin in the condemned cell, Bill Sikes's terrifying demise, and the Artful Dodger's jaunty confidence became inseparable from Dickens's characters in the public imagination. These images were not mere decorations; they were powerful interpretations that amplified the novel's melodrama, pathos, and social critique. The collaboration, however, was not without friction, particularly later in life when Cruikshank controversially claimed to have originated the plot of Oliver Twist, a claim vehemently denied by Dickens and his supporters.

Despite this later dispute, the impact of Cruikshank's work with Dickens was profound. It demonstrated the power of illustration to shape the reading experience and contribute significantly to a novel's success and enduring visual identity. His ability to translate complex characters and dramatic scenes into memorable graphic form set a high standard for book illustration in the Victorian era.

A Prolific Book Illustrator

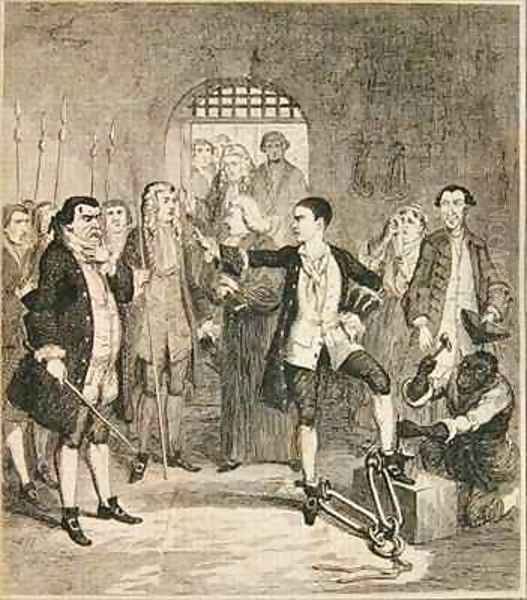

Cruikshank's work as a book illustrator extended far beyond Dickens. His output was immense, encompassing hundreds of volumes. He illustrated classics like Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe and Oliver Goldsmith's The Vicar of Wakefield. He had a long and fruitful collaboration with the popular historical novelist William Harrison Ainsworth, providing dramatic and often gruesome illustrations for works such as Jack Sheppard (1839), The Tower of London (1840), and Windsor Castle (1843). His detailed, atmospheric etchings perfectly complemented Ainsworth's blend of history, romance, and gothic horror.

He also turned his attention to folklore and fairy tales. His George Cruikshank's Fairy Library (1853-1864) involved retelling classic stories like "Cinderella" and "Jack and the Beanstalk." However, this project became controversial because Cruikshank, increasingly devoted to the cause of temperance, rewrote the tales to include overt anti-alcohol messages. This didactic approach drew criticism from many, including Charles Dickens, who felt it violated the spirit of the original stories.

Throughout his career, Cruikshank illustrated almanacs, songbooks, pamphlets, and periodicals. His Comic Almanack (1835-1853) was a popular annual publication filled with humorous illustrations, verses, and satirical observations on the events of the year. The sheer breadth and volume of his illustrative work are staggering, reflecting both his incredible industry and the enormous demand for illustrated material in the 19th century.

The Temperance Crusader

In the later decades of his life, George Cruikshank underwent a significant personal transformation, becoming a fervent advocate for the temperance movement and total abstinence from alcohol. This cause came to dominate his artistic output and public persona. Having witnessed the devastating effects of alcoholism in London society, and perhaps reflecting on his own past indulgences, he dedicated his art to warning against the dangers of drink.

His most famous work in this vein was The Bottle (1847), a series of eight large plates depicting the tragic downfall of a family due to the father's descent into alcoholism. Presented as a sequential narrative, moving from domestic comfort to ruin, destitution, insanity, and violence, The Bottle was a powerful piece of visual propaganda. Its cheap production and melodramatic storytelling made it incredibly popular and influential. It sold hundreds of thousands of copies, was adapted into stage plays, and became a cornerstone of temperance campaigns.

He followed this success with a sequel, The Drunkard's Children (1848), which continued the grim narrative, showing the blighted lives of the offspring from the original story. These works marked a stylistic shift for Cruikshank. While still detailed, the emphasis moved from caricature and humour towards stark melodrama and moral instruction. Though sometimes criticized for their heavy-handedness, these temperance works had a significant social impact, tapping into widespread Victorian anxieties about poverty, crime, and social order, and the perceived role of alcohol in exacerbating these problems.

Style, Technique, and Artistic Context

George Cruikshank's style is instantly recognizable. His primary medium for his published work was etching, a technique he mastered early and employed with extraordinary skill and speed throughout his career. His line is typically thin, wiry, and energetic, creating figures that often seem to vibrate with life or nervous tension. He excelled at depicting crowds and complex scenes, filling his compositions with intricate details and secondary characters that added layers of meaning and humour.

While capable of subtlety, Cruikshank often favoured exaggeration and the grotesque, particularly in his caricatures. He had an uncanny ability to capture personality through distorted features and expressive body language. Yet, he could also evoke genuine pathos, as seen in his illustrations for Oliver Twist or his temperance narratives. His work often balances humour with horror, comedy with tragedy, reflecting the dramatic contrasts of the society he depicted.

Cruikshank's career bridged the gap between the "Golden Age" of Georgian caricature (Hogarth, Gillray, Rowlandson) and the rise of Victorian illustrated journalism, exemplified by magazines like Punch. He was deeply influenced by William Hogarth (1697-1764), particularly in his use of narrative sequences and his focus on moral themes, leading to the frequent "modern Hogarth" comparison. He learned from the political bite of Gillray and the social observation of Rowlandson, as well as from his own father, Isaac Cruikshank.

He worked alongside contemporaries who also shaped Victorian illustration, such as Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz," 1815-1882), another key Dickens illustrator, and John Leech (1817-1864), a mainstay of Punch magazine known for his gentler social satire. Later Victorian illustrators like John Tenniel (1820-1914), famous for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, built upon the traditions established by Cruikshank and his peers. While the grand landscape painting of J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and John Constable (1776-1837), or the detailed realism of the Pre-Raphaelites like John Everett Millais (1829-1896) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), represented different strands of British art, Cruikshank's graphic work arguably had a more direct and widespread impact on popular visual culture.

Later Years, Disputes, and Legacy

George Cruikshank remained active well into old age, a testament to his remarkable energy and dedication. He continued to exhibit drawings and watercolours, and fiercely defended his artistic reputation. However, his later years were not without difficulties. His outspoken temperance advocacy sometimes alienated former associates. His claims regarding the genesis of Oliver Twist led to public controversy. Furthermore, as mentioned in historical accounts, disputes with publishers over creative control or financial arrangements sometimes marked his later career.

He suffered a stroke in his final years, which inevitably impacted his ability to work with the same intensity. George Cruikshank died in London on February 1, 1878, at the age of 85. He was initially buried in Kensal Green Cemetery, but his remains were later exhumed and reinterred in St. Paul's Cathedral, a significant honour reflecting his status as a national figure.

His legacy is immense and multifaceted. As a caricaturist, he was one of the last great practitioners of the robust Georgian tradition, adapting it for a Victorian audience. As a book illustrator, he was a pioneer who demonstrated the crucial role visuals could play in the success and interpretation of literature, particularly the novel. His work for Dickens and Ainsworth remains iconic. As a social commentator and campaigner, particularly through his temperance art, he used his graphic skills to engage directly with the pressing social issues of his day, reaching a vast public and contributing to social change movements.

George Cruikshank's influence extended to subsequent generations of illustrators and cartoonists in Britain and beyond. His dynamic style, his blend of humour and social critique, and his sheer productivity set a benchmark. Though tastes and artistic styles have changed, his work remains a vital and vivid window into the society, politics, and culture of 19th-century Britain, securing his place as a giant of graphic art. He was far more than just an illustrator; he was a visual chronicler of his age.