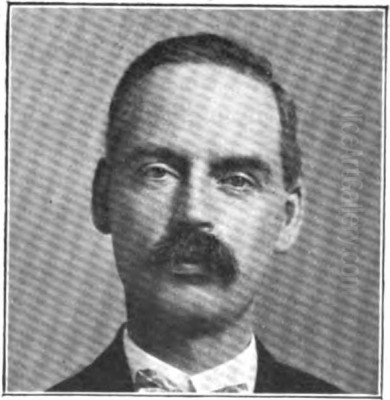

Charles Edmund Brock (1870-1938) stands as a distinguished figure in the annals of British art, particularly celebrated for his prolific and enchanting contributions to book illustration during its "Golden Age." An artist gifted with an innate ability to capture the essence of characters and the nuances of bygone eras, Brock's work is characterized by its delicate yet expressive line work, its harmonious use of color, and its deep sympathy for the literary worlds he brought to visual life. His illustrations, particularly for the novels of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, have become iconic, shaping the visual understanding of these classic texts for generations of readers.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in Holloway, London, on February 5, 1870, Charles Edmund Brock was the eldest of four brothers, all of whom would eventually pursue artistic careers, though Charles and his younger brother Henry Matthew (H.M.) Brock would achieve the most widespread recognition. His father, Edmund Brock, was a reader for a publisher, and this literary environment likely played a role in fostering an appreciation for books and storytelling in the young Charles. The family later moved to Cambridge, a city that would become central to Brock's life and work.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who underwent rigorous academic training in established art schools, C.E. Brock's formal artistic education was relatively brief. He received some guidance from the sculptor Henry Wiles, which may have contributed to his strong sense of form and three-dimensionality in his drawings. However, much of his skill appears to have been honed through dedicated self-study and practice, driven by a natural talent and a keen observational eye. This independent path allowed him to develop a distinctive style that, while rooted in tradition, possessed a fresh and personal quality.

His passion for drawing was evident from an early age. The rich historical atmosphere of Cambridge, with its ancient university buildings and scholarly traditions, undoubtedly provided a stimulating backdrop for an aspiring artist with a penchant for historical subjects. This environment, coupled with his family's literary connections, set the stage for a career that would beautifully merge the visual and the textual.

The Dawn of a Prolific Career

C.E. Brock received his first professional book illustration commission at the remarkably young age of twenty. This early success was a testament to his already considerable skill and marked the beginning of a long and fruitful career. He quickly established himself as a reliable and talented illustrator, sought after by publishers for his ability to create images that were not merely decorative but genuinely enhanced the reader's engagement with the narrative.

His early works demonstrated a versatility that would become a hallmark of his career. He could adapt his style to suit a range of literary genres, from adventure stories to period dramas and children's tales. Publishers like Macmillan and J.M. Dent & Co. were among those who frequently commissioned his work, recognizing his ability to deliver high-quality illustrations that appealed to a broad audience.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a fertile period for book illustration, often referred to as the Golden Age. Advances in printing technology allowed for more faithful reproduction of artists' work, including delicate line drawings and subtle color washes. Artists like C.E. Brock, Hugh Thomson, Arthur Rackham, and Edmund Dulac rose to prominence during this era, each bringing their unique vision to the illustrated book. Brock, alongside Thomson, became particularly known for his charming and historically sensitive depictions of Regency and 18th-century life.

The Cambridge Studio and Sibling Collaboration

A significant aspect of C.E. Brock's professional life was his close working relationship with his brother, Henry Matthew Brock (1875-1960), also a highly accomplished illustrator. The Brock brothers shared a studio in Cambridge, a space that became a creative hub filled with an eclectic collection of antiques, period costumes, furniture, and reference materials. This carefully curated environment was invaluable for ensuring the historical accuracy and authentic atmosphere that characterized their illustrations, particularly those set in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Their shared studio was not just a workspace but a repository of visual information. When illustrating a scene from a Jane Austen novel, for example, they could refer to actual Regency-era clothing or furniture, lending a tangible sense of realism to their drawings. This dedication to authenticity set their work apart and was deeply appreciated by both publishers and the reading public.

While their styles had individual nuances – C.E. Brock's line often perceived as slightly more delicate and refined, and H.M. Brock's perhaps more robust or overtly humorous at times – their work was often complementary. They sometimes collaborated on projects, and their shared resources and mutual artistic support undoubtedly contributed to their individual successes. The public occasionally confused the two due to their similar initials and artistic focus, a testament to their shared prominence in the field. This collaborative spirit extended to the broader artistic family, creating a supportive and stimulating environment for their creative endeavors.

Illustrating the Classics: Jane Austen

C.E. Brock's name is inextricably linked with his illustrations for the novels of Jane Austen. His interpretations of Austen's world, first appearing in the Macmillan editions of the 1890s, are considered by many to be definitive. He possessed an uncanny ability to capture the subtle social satire, the romantic sensibilities, and the distinct personalities of Austen's characters. His depictions of Elizabeth Bennet, Mr. Darcy, Emma Woodhouse, and Anne Elliot, among others, have become deeply ingrained in the popular imagination.

For Pride and Prejudice (1895), Brock created a series of illustrations that perfectly conveyed the wit and elegance of Austen's narrative. His drawings captured the nuances of Regency fashion, the decorum of social interactions, and the emotional undercurrents of the story. Scenes such as Elizabeth Bennet's spirited exchanges with Mr. Darcy or the bustling social life of Meryton were brought to life with a light touch and an eye for detail.

His work on Emma (1898), Sense and Sensibility (1898), Mansfield Park (1908), Persuasion (1897), and Northanger Abbey (1897) further solidified his reputation as a master interpreter of Austen. He understood the importance of character expression and body language in conveying Austen's subtle psychological insights. His heroines are portrayed with intelligence and charm, while the supporting cast is rendered with a delightful individuality that reflects Austen's own keen observations of human nature. The influence of earlier illustrators like Hugh Thomson, who had also famously illustrated Austen, can be seen, but Brock developed his own distinct and enduring vision.

Venturing into Dickens and Other Literary Giants

Beyond Jane Austen, C.E. Brock lent his illustrative talents to a wide array of classic authors. His work for Charles Dickens's novels and Christmas stories, such as A Christmas Carol and The Cricket on the Hearth, showcased his ability to adapt his style to Dickens's more robust and often more somber or caricatured world. He captured the Victorian atmosphere, the pathos, and the humor inherent in Dickens's writing, creating memorable images of characters like Ebenezer Scrooge and the Cratchit family.

Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1894) provided another canvas for Brock's imagination, allowing him to explore fantastical lands and satirical themes. He illustrated works by William Makepeace Thackeray, including The History of Henry Esmond and Vanity Fair, demonstrating his skill in depicting the complexities of 18th and early 19th-century society. His illustrations for George Eliot's Silas Marner (1905) captured the rustic charm and emotional depth of the novel.

Sir Walter Scott's historical romances, such as Ivanhoe (1897), also benefited from Brock's meticulous attention to period detail and his ability to convey dramatic action. He illustrated E. Nesbit's beloved children's classic, The Railway Children (1906), with a warmth and sensitivity that perfectly matched the story's charm. This breadth of work demonstrates his versatility and his deep engagement with English literature across different periods and styles. His contemporaries, such as Walter Crane and Randolph Caldecott, had paved the way for such rich literary illustration, and Brock built upon this tradition with his own unique contributions.

Artistic Style and Techniques

C.E. Brock's artistic style is distinguished by several key characteristics. His mastery of pen and ink was fundamental. He employed a fine, controlled line that could be both delicate and expressive, capable of rendering intricate details of costume and setting as well as the subtle nuances of facial expression. His use of cross-hatching and stippling added depth and texture to his black and white illustrations, creating a rich tonal range.

When working in color, Brock typically used watercolor washes, often in a subtle and harmonious palette. His color illustrations possess a gentle luminosity that enhances the period feel of his subjects. He understood how color could evoke mood and atmosphere, from the bright elegance of a Regency ballroom to the cozy warmth of a Victorian fireside. Unlike some of his contemporaries, such as Kay Nielsen or Edmund Dulac, whose color work was often more opulent or fantastical, Brock's use of color remained grounded in a gentle realism that suited the literary texts he illustrated.

Compositionally, Brock's illustrations are well-balanced and thoughtfully arranged. He had a strong sense of narrative, ensuring that his images effectively conveyed key moments in the story. His figures are gracefully posed and interact convincingly within their environments. He paid close attention to historical accuracy in costume, architecture, and furnishings, drawing upon the extensive collection in his Cambridge studio. This commitment to authenticity was a defining feature of his work and contributed significantly to its enduring appeal. His ability to convey character through posture, gesture, and expression was particularly noteworthy, bringing a psychological depth to his portrayals.

Beyond Book Illustration: Paintings and Other Works

While C.E. Brock is primarily celebrated for his book illustrations, he was also an accomplished painter in oils and watercolors. He produced portraits, genre scenes, and historical subjects. One notable example of his oil painting is The Reverend Charles Taylor, DD, Fellow, a formal portrait held at St John's College, Cambridge, which demonstrates his skill in a more academic mode of representation.

His painting Circe and the Sirens (1925) showcases his engagement with classical mythology, a subject popular with many artists of the period, including figures like John William Waterhouse or earlier Pre-Raphaelites such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti. This work reveals a different facet of his artistic interests, moving beyond the confines of literary illustration into more allegorical or imaginative realms.

Brock was an active member of the artistic community. He was elected a member of the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours (RI) in 1908, a prestigious recognition of his skill in the medium. He also joined the Society of Graphic Art in 1921. He exhibited his work regularly, and his paintings and drawings were well-received. These activities indicate his engagement with the broader art world beyond the specific demands of publishing. His work, like that of many illustrators of his time, bridged the gap between commercial art and fine art.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

C.E. Brock worked during a vibrant period for British art and illustration. He was part of a generation of artists who benefited from new printing technologies and a burgeoning market for illustrated books and periodicals. His style, particularly in his Regency illustrations, is often compared to that of Hugh Thomson (1860-1920), who was a major influence in popularizing the charming, detailed depiction of 18th and early 19th-century life. Both artists shared a meticulous approach to historical detail and a light, elegant touch.

Other prominent illustrators of the Golden Age included Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), known for his fantastical and often grotesque imagery; Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), whose work was characterized by its exoticism and rich, jewel-like colors; and Kay Nielsen (1886-1957), celebrated for his elegant Art Nouveau and Art Deco-influenced fairy tale illustrations. While Brock's style was generally more naturalistic and less overtly stylized than these artists, he shared their commitment to craftsmanship and imaginative interpretation.

The legacy of earlier Victorian illustrators like John Tenniel (Alice in Wonderland) and narrative painters like William Powell Frith (Derby Day, The Railway Station) also formed part of the artistic backdrop. In America, illustrators like Howard Pyle and his student N.C. Wyeth were creating powerful images for classic adventure stories, contributing to the international flourishing of illustration. C.E. Brock's work, with its focus on character and historical setting, carved out a distinct and respected niche within this diverse and talented field. He also illustrated for popular magazines of the day, such as The Quiver, The Strand Magazine, and Pearson's Magazine, placing his work alongside that of many other notable illustrators.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

C.E. Brock continued to work as an illustrator and painter throughout the early decades of the 20th century. However, the taste for highly detailed, narrative illustration began to wane somewhat after the First World War, with new artistic movements and printing economies favoring different styles. Despite these shifts, Brock's classic illustrations, particularly for Austen and Dickens, remained popular and were frequently reprinted.

He largely ceased producing new book illustrations after around 1910, though his existing work continued to be published. He remained in Cambridge, a city that had been so integral to his life and art. Charles Edmund Brock passed away on February 28, 1938, in Cambridge, leaving behind a rich legacy of artistic achievement.

His illustrations have endured because they possess a timeless charm and a genuine understanding of the texts they accompany. They avoid sentimentality while capturing the warmth, humor, and emotional depth of the stories. For many readers, C.E. Brock's images are inseparable from their experience of reading Jane Austen or Charles Dickens. His work is preserved in numerous collections, and original drawings and first editions featuring his illustrations are highly sought after by collectors. The British Museum of Illustration, for instance, holds examples of his work, recognizing his significant contribution to the art form.

Critical Reception and Lasting Appeal

Throughout his career and posthumously, C.E. Brock has been praised for his technical skill, his historical accuracy, and his sympathetic interpretations of literary characters. Critics and the public alike appreciated the elegance and refinement of his line, the harmony of his compositions, and the gentle humor that often pervaded his work. He was seen as an artist who respected the author's intent while bringing his own creative vision to the page.

His ability to create a believable and engaging visual world for classic novels has ensured his lasting appeal. In an age before film and television dominated visual storytelling, illustrators like Brock played a crucial role in shaping how readers visualized these narratives. His work helped to make classic literature accessible and enjoyable for a wide audience, including younger readers.

The enduring popularity of Jane Austen's novels, in particular, has kept Brock's illustrations in the public eye. Many modern editions of Austen continue to feature his work, a testament to its timeless quality and its perfect marriage with the spirit of the texts. He managed to capture a sense of period authenticity without his drawings ever feeling stiff or merely academic; they are imbued with life and personality. This balance of historical fidelity and artistic vitality is key to his enduring success.

Conclusion: An Illustrator of Enduring Charm

Charles Edmund Brock was more than just a skilled draftsman; he was a sensitive interpreter of literature, an artist who could translate the written word into compelling visual narratives. His contributions to the Golden Age of Illustration were substantial, and his work continues to delight and inspire. From the witty drawing-rooms of Jane Austen's England to the bustling streets of Dickens's London, Brock's illustrations transport readers to other times and places with an unmatched grace and authenticity.

His dedication to his craft, his meticulous attention to detail, and his profound understanding of character have secured his place as one of Britain's most beloved illustrators. The legacy of C.E. Brock lives on in the pages of the countless books he adorned, his art serving as a timeless bridge between the literary imagination and the visual world, enriching the reading experience for all who encounter his charming and insightful creations. His work remains a benchmark for classic literary illustration, admired for its elegance, its historical integrity, and its deep empathy for the human condition as portrayed by some of the greatest authors in the English language.