Hablot Knight Browne, far better known by his charming pseudonym 'Phiz', stands as one of the most significant and prolific illustrators of the 19th century in Britain. His name is inextricably linked with that of the literary giant Charles Dickens, for whose novels he provided the visual interpretations that have shaped readers' imaginations for generations. Active during a vibrant period of print culture and novelistic production, Phiz's etchings and drawings brought to life a sprawling cast of characters and captured the unique atmosphere of Victorian England, from its bustling, grimy streets to its cozy hearths and desolate landscapes. Born in 1815 and passing away in 1882, his career spanned a crucial era of artistic and social change, leaving an indelible mark on the history of illustration and literature.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Hablot Knight Browne entered the world on June 15, 1815, in Lambeth, London. His parentage holds a touch of intrigue; while officially the son of William Loder Browne, a merchant, and his wife Katherine, biographical accounts often suggest he was the illegitimate son of Captain Nicolas Hablot, a French officer of Napoleon's Imperial Guard, from whom his distinctive first name derived. This narrative adds a layer of romance and complexity to his origins, fitting perhaps for an artist who would later excel at depicting the dramatic and the unexpected.

Tragedy struck the Browne family early. William Loder Browne died when Hablot was just seven years old, leaving the family in significantly reduced circumstances. This financial hardship undoubtedly shaped the young Browne's future path. Showing artistic promise, his future was supported by his maternal uncle, Elhanan Bicknell. Bicknell was a notable patron of the arts and a successful businessman, known for his impressive collection that included works by J.M.W. Turner. Recognizing his nephew's talent, Bicknell financed Hablot's apprenticeship.

Around the age of fourteen, Browne was placed in the studio of William Finden, a respected engraver in London. Here, he was meant to learn the meticulous craft of steel engraving, a dominant medium for reproduction at the time. The training under Finden would have involved rigorous exercises in drawing, copying, and mastering the burin. However, Browne reportedly found the painstaking process of engraving tedious and unsuited to his temperament, which leaned more towards rapid, expressive drawing and invention.

Despite his disinclination towards pure engraving, his training provided a foundational understanding of printmaking techniques. His natural talent for drawing and composition soon became evident. In 1833, while still an apprentice or shortly thereafter, he won a prize from the Society of Arts for a spirited etching titled "John Gilpin's Ride," based on William Cowper's popular comic poem. This early success hinted at his potential in the field of original illustration rather than reproductive engraving. He soon abandoned the path of the engraver to pursue drawing, watercolour, and, most importantly, etching as a primary means of artistic expression. He briefly shared a studio with fellow artist Robert Young; some sources mention a partnership with a Robert Fawcett, where one focused on drawing and the other on printing, highlighting Browne's early engagement with the practicalities of print production.

The Dawn of 'Phiz': The Dickens Partnership

The pivotal moment in Hablot Knight Browne's career arrived in 1836. Charles Dickens, then a rising literary star known as 'Boz', was enjoying phenomenal success with his serialized novel, The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. The novel's original illustrator, Robert Seymour, had tragically died by suicide after completing illustrations for only the first two installments. A replacement was urgently needed. Dickens and his publishers, Chapman and Hall, considered several artists, including the already famous George Cruikshank and the talented John Leech.

The young Hablot Browne submitted speculative drawings for the novel. Dickens was impressed by Browne's ability to capture the humour and energy of his characters. Although William Makepeace Thackeray also applied for the position, Browne was chosen, initially to work alongside R.W. Buss on the third installment. Buss's contributions were deemed unsatisfactory, and from the fourth installment onwards, Browne became the sole illustrator for Pickwick.

To complement Dickens's pseudonym 'Boz', Browne adopted the pen name 'Phiz'. This choice was reportedly made to create a harmonious pairing ('Boz' and 'Phiz' sounding good together) and perhaps reflected the effervescent, sparkling quality he brought to the illustrations. The name stuck, and under it, Browne embarked on one of the most famous author-illustrator collaborations in English literary history.

The success of Pickwick Papers was astronomical, and Phiz's illustrations were integral to its appeal. His depictions of Mr. Pickwick, Sam Weller, Alfred Jingle, and the host of other eccentric characters became the definitive visual representations. This marked the beginning of a partnership that would span over two decades and ten major novels. Phiz became Dickens's principal illustrator, visually shaping the public's perception of the author's fictional world.

Illustrating the Dickensian World: Style and Technique

Phiz's primary medium for the Dickens illustrations was etching, usually on steel plates. Steel engraving allowed for finer lines and larger print runs than copperplate etching, which was essential for the mass circulation of serialized novels. Phiz would typically create a drawing, transfer it to the prepared plate, and then etch the lines using acid. This technique allowed for a lively, linear style well-suited to narrative and caricature.

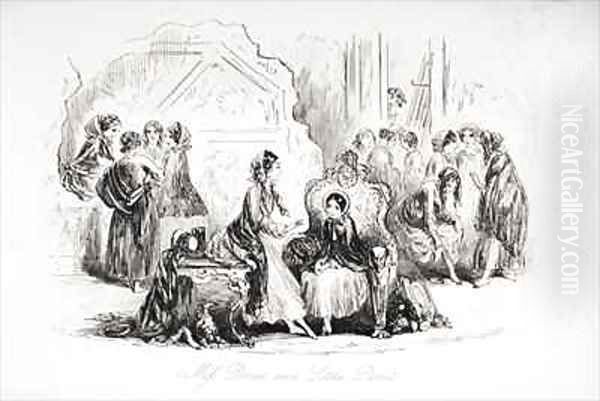

His style evolved over the course of his collaboration with Dickens. The early illustrations for Pickwick Papers and Nicholas Nickleby are characterized by exuberant energy, broad humour, and sometimes slightly chaotic compositions, perfectly matching the picaresque nature of the early novels. He excelled at capturing physical comedy and eccentric personalities through posture, gesture, and facial expression. His crowd scenes were often teeming with life and individual details.

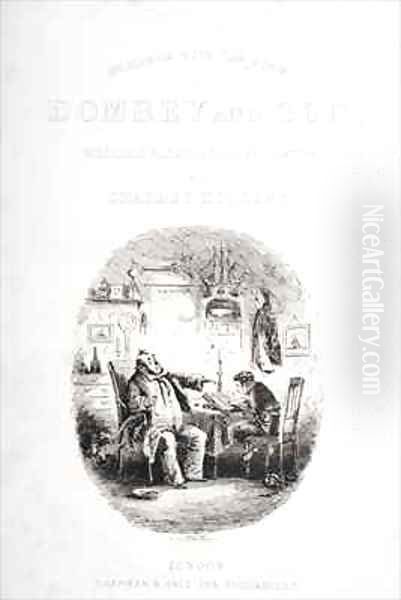

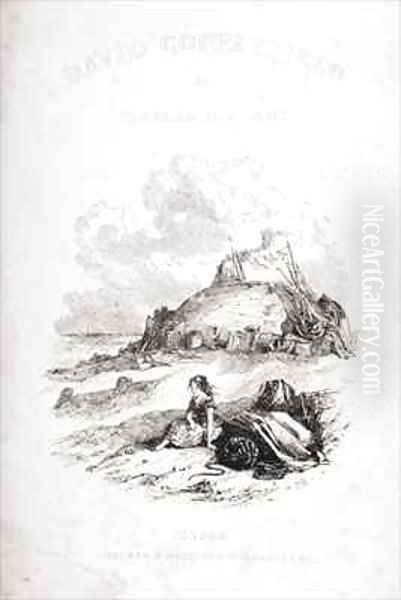

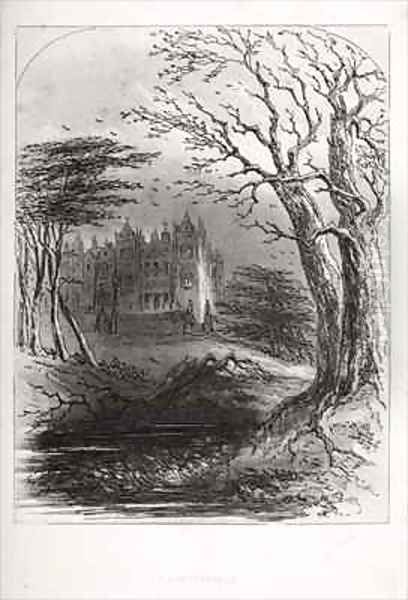

As Dickens's novels grew darker and more complex, exploring themes of social injustice, poverty, and psychological depth, Phiz's style adapted. In works like Dombey and Son, David Copperfield, and particularly Bleak House, his illustrations took on a more atmospheric and symbolic quality. He became a master of using light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to create mood and drama.

A notable innovation associated with Phiz is the "dark plate" technique, used extensively in Bleak House. This involved ruling the steel plate with fine lines using a machine, then scraping away areas to create highlights, resulting in prints with rich, dark, mezzotint-like tones. These dark plates powerfully conveyed the fog, gloom, and moral ambiguity pervading the novel, such as the haunting depictions of Tom-All-Alone's or the sinister Tulkinghorn's chambers.

Phiz possessed a remarkable ability to translate Dickens's prose into visual equivalents. He often embedded symbolic details within his illustrations, echoing the novel's themes – clocks indicating the passage of time or impending doom, tangled lines suggesting complex plots, or animals mirroring human characteristics. While sometimes criticized for occasional weaknesses in anatomy or perspective, his strength lay in characterization, narrative clarity, and atmospheric rendering. He populated Dickens's world with unforgettable images: the fragile pathos of Little Nell, the sinister menace of Quilp, the comic absurdity of Mrs. Gamp, the decaying grandeur of Miss Havisham's Satis House (though his work on Great Expectations was limited).

Beyond etching, Phiz also worked in wood engraving, particularly later in his career when it became the preferred medium for illustrated magazines. He was also a capable watercolourist, though his paintings never achieved the fame or impact of his illustrative work. His primary contribution and enduring legacy remain his etched illustrations for novels.

Beyond Dickens: Other Literary Collaborations

While the Dickens partnership defined Phiz's career, he was a highly sought-after illustrator who worked with numerous other popular authors of the Victorian era. His distinctive style graced the pages of novels by Charles Lever, an Irish writer known for his rollicking military and adventure stories. Phiz illustrated many of Lever's most famous works, including Harry Lorrequer, Charles O'Malley, the Irish Dragoon, and Tom Burke of "Ours". His energetic and often humorous style was well-suited to Lever's boisterous narratives.

Another significant collaboration was with William Harrison Ainsworth, a writer specializing in historical romances, often with gothic undertones. Phiz provided illustrations for several of Ainsworth's novels, such as Mervyn Clitheroe, Old St. Paul's: A Tale of the Plague and the Fire, and Crichton. These commissions allowed Phiz to explore different historical settings and moods, often requiring dramatic and atmospheric scenes.

He also illustrated works by Frank Smedley (e.g., Frank Fairlegh), Augustus Mayhew, and others, demonstrating his versatility and prominence in the publishing world of his time. These collaborations, while perhaps less iconic than his work for Dickens, showcase the breadth of his output and his ability to adapt his style to different literary genres. His illustrations were a significant selling point for these novels, confirming his status as a leading commercial artist.

Phiz and His Contemporaries: The Victorian Illustration Scene

Hablot Knight Browne worked during a golden age of British illustration, alongside a host of talented artists. Understanding his place requires acknowledging his peers, rivals, and collaborators. His most direct predecessor and contemporary in the Dickensian sphere was George Cruikshank. Cruikshank, an established master of caricature and etching, illustrated Dickens's early works like Sketches by Boz and Oliver Twist. Their styles differed; Cruikshank's was often more grotesque and sharply satirical. While initially Dickens's primary illustrator, disagreements led to a parting of ways, paving the path for Phiz's long tenure.

John Leech was another major figure, famous for his work in Punch magazine and his illustrations for Dickens's A Christmas Carol. Leech's style was generally gentler and more focused on social comedy than Cruikshank's or Phiz's, though he could certainly handle pathos. Phiz, Cruikshank, and Leech formed a triumvirate of sorts, dominating narrative illustration in the mid-19th century, each with a distinct visual voice.

Other important illustrators of the era included:

Robert Seymour: The tragic first illustrator of Pickwick.

Daniel Maclise: A painter and friend of Dickens, who provided some illustrations, notably for The Old Curiosity Shop and the frontispieces for several novels.

Clarkson Stanfield: Another painter friend of Dickens, known for his seascapes, who contributed illustrations, particularly for the Christmas Books.

Richard Doyle: Known as 'Dicky' Doyle, famous for his fairy illustrations and work for Punch, including designing its original cover.

John Tenniel: Immortalized by his illustrations for Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, also a principal cartoonist for Punch.

George Du Maurier: Leech's successor at Punch, later famous as the author of Trilby. His illustrative style was more elegant and focused on society manners.

Marcus Stone: Chosen by Dickens to illustrate Our Mutual Friend, representing a shift towards a more realistic, less caricatural style in later Victorian illustration.

Luke Fildes: Illustrated Dickens's final, unfinished novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, known for his powerful social realist paintings like Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward.

William Powell Frith: Though primarily a painter, his detailed narrative canvases like Derby Day and The Railway Station share the Victorian fascination with contemporary life and character found in illustrations.

John Everett Millais: A leading Pre-Raphaelite painter who also produced significant work as an illustrator, particularly for Trollope's novels, bringing a different aesthetic sensibility to the field later in the century.

Myles Birket Foster: A highly popular landscape painter and illustrator, known for his charming rustic scenes often reproduced via wood engraving.

Phiz navigated this competitive landscape successfully for many years. His style, while perhaps less technically refined than some academic painters who turned to illustration, possessed a unique dynamism and an unparalleled ability to connect with the spirit of the text, especially Dickens's blend of comedy, melodrama, and social commentary.

Artistic Methods and the Publishing Context

Phiz's success was tied to the burgeoning print market and the rise of the serialized novel. Monthly installments required illustrations to be produced quickly and reliably. Steel etching was ideal for this, allowing for relatively swift execution once the design was finalized and enabling the printing of thousands of copies before the plate wore out significantly.

However, for extremely large print runs, even steel plates could wear down. Publishers sometimes had duplicate plates etched (often by assistants or other engravers copying the primary artist's work) to speed up printing or replace worn-out originals. This means that the quality of Phiz's prints can vary depending on the state of the plate (early, sharp impressions being more desirable than later, worn ones) and whether it was etched by Phiz himself or a copyist.

The process often involved close collaboration, or at least communication, between author and illustrator. Dickens was known to be quite specific about the subjects he wanted illustrated, sometimes providing detailed instructions or discussing scenes with Phiz. The illustrations were not mere decorations; they were integral parts of the narrative experience for contemporary readers, often revealing plot points or emphasizing character traits before the reader encountered them in the text.

Later in his career, Phiz adapted to the growing preference for wood engraving, which allowed illustrations to be printed alongside text more easily. However, his most characteristic and celebrated work remains his steel etchings. The decline of steel etching as the dominant illustrative medium, coupled with changing artistic tastes favouring greater realism, contributed to the waning of Phiz's popularity in his later years.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Later Life

While primarily known as an illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne did pursue other artistic avenues, including watercolour painting, and occasionally exhibited his work. He showed pieces at institutions like the Royal Academy and the British Institution, though his reputation as a painter never rivaled his fame as 'Phiz'. His 1833 Society of Arts prize for "John Gilpin" remained an important early validation.

His long service to literature and art did receive formal acknowledgement later in life. In 1878, the Royal Academy granted him an annuity in recognition of his contributions as an artist, a gesture that likely provided some much-needed financial support during his declining years.

The collaboration with Dickens ended somewhat abruptly after A Tale of Two Cities in 1859. Reasons cited include Dickens's growing dissatisfaction, a desire for a more modern illustrative style (leading him to employ Marcus Stone and Luke Fildes), and perhaps a cooling of their personal relationship. This marked a significant turning point in Phiz's career, depriving him of his most prestigious and consistent source of work.

A more devastating blow came in 1867 when Phiz suffered a stroke. This left him partially paralyzed, severely impairing his ability to draw and etch with his former dexterity and speed. Although he continued to work, producing illustrations for magazines and less demanding commissions, the quality inevitably declined. His later work often lacks the vigour and precision of his prime.

His health continued to deteriorate, compounded by financial worries. He eventually moved from London to Brighton, seeking the sea air for his health. Hablot Knight Browne 'Phiz' died there on July 8, 1882, at the age of 67.

Legacy and Market Reception

Hablot Knight Browne's legacy is immense, though intrinsically tied to Charles Dickens. For millions of readers, Phiz's images are Mr. Pickwick, Micawber, Sairey Gamp, Captain Cuttle, and countless others. He visually defined the Dickensian universe, capturing its energy, humour, squalor, and sentimentality in a way that no other illustrator quite matched. His work fixed these characters in the popular imagination, influencing subsequent adaptations in theatre, film, and television.

In the art market, Phiz's work remains highly collectible. Original drawings and watercolours command significant prices, valued for their immediacy and connection to the creative process. Prints from the Dickens novels are widely collected, with value depending heavily on the edition (first editions in original parts being most desirable), the state of the plate (early, clear impressions fetch higher prices), and the condition of the print. Institutional collections, such as the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum in London, hold extensive collections of his prints.

While art historical assessments acknowledge his occasional technical limitations, his strengths in narrative, characterization, and atmosphere are widely praised. He is recognized as a master of etching and a key figure in the history of book illustration. His influence extended to subsequent generations of illustrators working in the narrative and caricature traditions.

Conclusion: The Enduring Vision of Phiz

Hablot Knight Browne 'Phiz' was more than just an illustrator; he was a visual storyteller who worked in perfect, albeit sometimes fraught, harmony with one of the greatest narrative geniuses of English literature. His etchings did not merely accompany Dickens's text; they amplified it, providing a visual counterpoint that enriched the reading experience for contemporary audiences and continues to shape our understanding of Dickens's world today. From the comic chaos of Pickwick to the brooding shadows of Bleak House, Phiz's art captured the multifaceted nature of Victorian life as depicted by Dickens. Though challenged by changing tastes and failing health in his later years, the vast body of work produced during his prime secures his position as a pivotal figure in 19th-century British art and an unforgettable interpreter of literary imagination. His 'Phiz' continues to sparkle on the pages he illuminated.