George Dunlop Leslie RA (2 July 1835 – 21 February 1921) was a distinguished English genre painter, author, and illustrator, whose career spanned a significant portion of the Victorian era and extended into the early 20th century. He became renowned for his charming and idyllic depictions of English life, particularly scenes featuring elegant young women and children in sun-dappled gardens or serene domestic interiors. While his later, more popular style diverged from his earlier Pre-Raphaelite inclinations, Leslie carved a distinct niche for himself, earning accolades, Royal Academy membership, and a lasting place in the narrative of British art.

Early Life and Artistic Lineage

Born in London, George Dunlop Leslie was immersed in art from his earliest days. He was the son of Charles Robert Leslie RA, a prominent and highly respected genre painter, known for his literary and historical subjects, often imbued with a gentle humour. The elder Leslie, an American by birth who had settled in England, was a friend to artists like John Constable and writers such as Washington Irving, ensuring young George grew up in a cultured and artistically stimulating environment. His uncle, Robert Leslie, was a marine painter, further cementing the family's artistic pedigree.

This familial background undoubtedly shaped George's path. He received his initial art education at Cary's Art School, a preparatory institution for many aspiring artists of the time. Following this, in 1854, he enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. Here, he would have received a traditional academic training, focusing on drawing from the antique and the live model, and studying the works of Old Masters. This foundational education was crucial, even for artists who later diverged from strict academic conventions.

The Royal Academy and Early Influences

Leslie began exhibiting at the Royal Academy in 1857, with his first painting being Hope. He would continue to exhibit there annually without fail for the rest of his long career. His early works, produced in the late 1850s and early 1860s, showed a discernible influence from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. This group, which included luminaries such as John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, advocated for a return to the detailed realism, intense colours, and complex compositions found in Quattrocento Italian art.

Leslie's paintings from this period, such as Matilda (1860), based on a character from Sir Walter Scott's poem "Rokeby," and The Defence of Lathom House (exhibited 1863), reflected this Pre-Raphaelite tendency towards historical or literary subjects, rendered with meticulous attention to detail and a bright palette. He was not a formal member of the Brotherhood but was clearly sympathetic to their aims of "truth to nature" and their rejection of the more formulaic and sentimental aspects of contemporary academic art, as championed by figures like Sir Charles Lock Eastlake.

His talent was recognized relatively early. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) on 25th June 1868, a significant step in an artist's career, and achieved full Academician status (RA) on 29th June 1876. This ascent within the RA hierarchy indicated his growing reputation and the esteem in which he was held by his peers.

The St John's Wood Clique

During the 1860s, Leslie became associated with a group of artists known as the St John's Wood Clique. This informal collective, which also included Philip Hermogenes Calderon, Henry Stacy Marks, William Frederick Yeames, George Adolphus Storey, and David Wilkie Wynfield (who was also a notable photographer), shared studios and often socialized together in the St John's Wood area of London. Frederick Walker was also loosely associated with this circle.

The Clique was known for its members' penchant for historical genre subjects, often with a light-hearted or anecdotal quality. They shared a commitment to careful draughtsmanship and narrative clarity, though their individual styles varied. Leslie's involvement with this group likely reinforced his interest in narrative painting and provided a supportive environment for artistic development. While they were not a revolutionary group like the Pre-Raphaelites, they represented a significant strand of popular Victorian art, producing works that were accessible and appealing to the burgeoning middle-class art market. Their camaraderie and shared artistic pursuits were typical of the close-knit nature of the London art world at the time.

Evolution of Style: The Idyllic and the Domestic

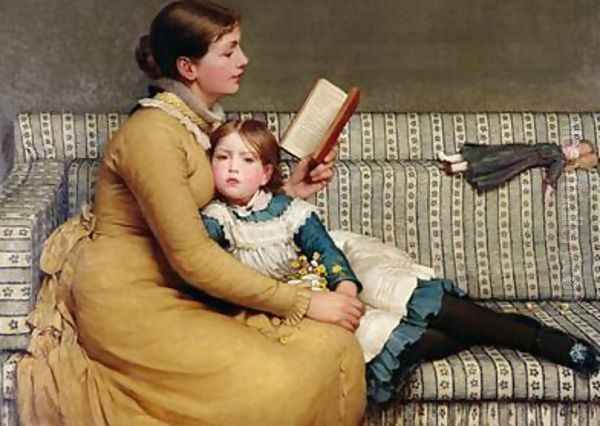

As his career progressed, Leslie's style gradually shifted away from the more intense historicism of his early Pre-Raphaelite-influenced phase. He developed a more personal and ultimately more popular idiom, focusing on contemporary scenes of English domestic life, particularly those set in picturesque gardens or refined interiors. His subjects often featured graceful young women, frequently his own daughters Alice and Lydia, and children engaged in quiet, leisurely pursuits.

These later works are characterized by their sunlit charm, delicate colour harmonies, and an atmosphere of serene, almost idealized, beauty. Paintings such as Pot Pourri (1874), School Revisited (1875), Cowslips (also known as The Path by the River), and Tea (1885) exemplify this mature style. His figures are typically elegant and well-dressed, inhabiting a world of genteel leisure and quiet contemplation. The settings, often meticulously rendered gardens filled with flowers, became a hallmark of his work. He had a particular fondness for the Thames Valley, and many of his scenes are set along its banks.

This shift towards a more overtly aesthetic and less narratively complex style was met with considerable public approval. His paintings were frequently praised for their refinement, their wholesome sentiment, and their technical accomplishment. The influential art critic John Ruskin, who had initially championed the Pre-Raphaelites, also admired Leslie's work, particularly his depictions of childhood innocence and the beauty of English girlhood. Ruskin's praise would have carried significant weight, further enhancing Leslie's reputation.

However, this stylistic evolution was not without its critics. Some contemporary and later commentators felt that Leslie had perhaps sacrificed some of the intellectual rigour and emotional depth of his earlier work for a more commercially appealing, albeit charming, aesthetic. This is a common trajectory for many Victorian artists who, having experimented with more challenging styles, found greater success and stability in producing works that resonated more directly with popular taste. Artists like Marcus Stone, a contemporary, also found immense popularity with similar, though perhaps more overtly sentimental, genre scenes.

Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

Leslie's oeuvre is extensive, but several works stand out as particularly representative of his artistic concerns and stylistic achievements.

_Matilda_ (1860): An early work showcasing Pre-Raphaelite influence in its detailed rendering and literary subject matter. The intensity of the figure and the careful depiction of natural elements are characteristic of this phase.

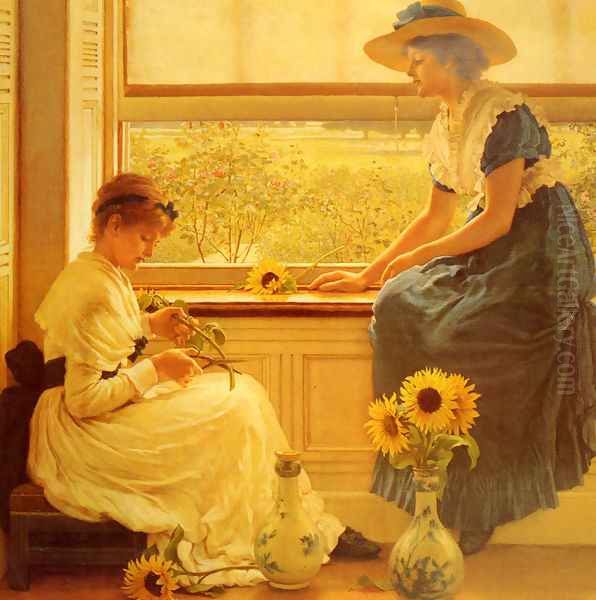

_Pot Pourri_ (1874): This painting, depicting two young women in an elegant interior carefully preparing dried flower petals, is a quintessential example of his mature style. The delicate play of light, the harmonious colours, and the atmosphere of quiet domesticity are all hallmarks of Leslie's work from this period. It evokes a sense of nostalgia and timeless grace.

_School Revisited_ (1875): Here, a young woman returns to her old school, a scene imbued with gentle nostalgia. The painting captures a moment of quiet reflection and the passage of time, themes that Leslie often explored.

_The Lass of Richmond Hill_ (1880s): This title, referencing a popular song, would have immediately resonated with Victorian audiences. The painting likely depicted an idealized vision of rustic beauty and romance, typical of Leslie's ability to tap into popular sentiment.

_Tea_ (1885): A charming scene of young women enjoying afternoon tea in a sunlit garden. This work perfectly encapsulates Leslie's focus on the refined pleasures of English domestic life and his skill in rendering light and atmosphere. The figures are elegant, the setting idyllic, and the overall mood one of peaceful contentment.

_Sun and Moon Flowers_ (1890): Exhibited at the Royal Academy, this painting, now in the Guildhall Art Gallery, London, depicts two young women in a garden, one holding sunflowers (sun flowers) and the other holding white daisies (moon flowers). It is a beautifully composed piece, celebrated for its delicate colour palette and the graceful portrayal of the figures.

_In the Wizard’s Garden_ (1904): This later work suggests a continued interest in slightly more imaginative or whimsical themes, though still rendered with his characteristic charm and technical finesse.

_Eve's Daughters_ (date uncertain, but likely late 19th/early 20th century): This painting gained renewed attention when it was rediscovered in a school in South Wales and sold for a significant sum (£170,000) at auction in the early 21st century. The work depicts several young women in a garden, embodying Leslie's idealized vision of femininity and natural beauty.

Throughout these works, common themes emerge: the beauty and innocence of childhood, the elegance and grace of young womanhood, the charm of English gardens and domestic interiors, and a gentle, often nostalgic, sentiment. His paintings offered an escape from the harsher realities of industrializing Britain, presenting an idealized vision of a more tranquil and harmonious world. This appealed greatly to Victorian sensibilities, which often valued art that was morally uplifting and aesthetically pleasing. His work can be seen in contrast to the social realism of artists like Hubert von Herkomer or Luke Fildes, who tackled more challenging contemporary social issues.

Leslie as a Writer and Illustrator

Beyond his prolific career as a painter, George Dunlop Leslie was also an accomplished writer and illustrator. His literary pursuits often complemented his artistic interests, focusing on the landscapes and traditions he cherished.

He authored several books, including:

_Our River_ (1881): A beautifully illustrated account of the River Thames, reflecting his deep affection for the waterway that so often featured in his paintings. The book combines personal reminiscences with observations on the river's scenery, history, and local life.

_Letters to Marco_ (1893): A collection of letters offering observations on nature and country life.

_Riverside Letters_ (1896): A sequel to _Letters to Marco_, continuing his reflections on the natural world.

_The Inner Life of the Royal Academy_ (1914): This book provides a valuable, albeit personal, insight into the workings and history of the institution with which he was so closely associated for much of his life. It offers anecdotes and observations about his fellow Academicians and the changing customs of the RA.

His writing style was engaging and accessible, much like his paintings. He also provided illustrations for several publications, including a notable edition of Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. His illustrative work shared the charm and clarity of his paintings. This dual career as painter and author was not uncommon in the Victorian era; figures like William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti were also accomplished in both visual art and literature.

Later Life, Residences, and Legacy

Leslie lived for many years in St John's Wood, the heart of his early artistic circle. Later, he resided at "Riverside," St. Leonard's Lane, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, a location that undoubtedly provided ample inspiration for his Thames-side scenes. In 1906, he moved to "Compton Cottage" in Lindfield, Sussex, where he spent his final years.

He remained an active exhibitor at the Royal Academy until his death. His last exhibited work, A Glimpse of the Test, Hampshire, was shown posthumously in 1921. George Dunlop Leslie passed away on 21 February 1921 in Lindfield.

His legacy is that of a skilled and sensitive chronicler of a particular aspect of Victorian and Edwardian England. While his art may not possess the dramatic power of some of his contemporaries like Lord Leighton or the intense symbolism of Edward Burne-Jones, it holds a distinct charm and offers a window into the refined sensibilities and aesthetic preferences of his time. His paintings celebrated a world of domestic harmony, natural beauty, and quiet grace, providing an antidote to the rapid industrial and social changes of the era.

His works are held in numerous public collections, including Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Guildhall Art Gallery in London, and various regional galleries throughout the United Kingdom. The continued interest in his paintings, as evidenced by auction prices and their inclusion in exhibitions of Victorian art, attests to their enduring appeal.

Market Reception and Controversies

Leslie's work enjoyed considerable popularity during his lifetime, translating into commercial success. His paintings were sought after by middle-class collectors who appreciated their accessible subject matter and pleasing aesthetics. The sale of engravings after his most popular works further broadened his audience.

In terms of controversies, Leslie's career was relatively untroubled compared to some of his more radical contemporaries. The main "controversy," if it can be called that, revolves around the aforementioned stylistic shift. Some critics felt his move towards more overtly charming and less intellectually demanding subjects represented a compromise of his earlier, Pre-Raphaelite-influenced potential. This is a debate common in art history: the tension between artistic innovation and commercial viability.

His relationship with the Royal Academy, while largely successful given his long tenure as an Academician, was not without its moments of friction. In The Inner Life of the Royal Academy, he recounts some of the internal politics and debates within the institution. There are mentions of his occasional dissatisfaction with RA policies, including an instance where he felt his work was unfairly treated or rejected, leading to spirited discussions. However, these seem to have been relatively minor disputes within the context of a long and generally harmonious association.

The rediscovery of Eve's Daughters and its high auction price in the 21st century brought Leslie's name back into public discussion, highlighting the potential for Victorian art to be re-evaluated and to find new appreciation in the contemporary art market. While some Victorian academic painters, like Lawrence Alma-Tadema or John William Waterhouse, have seen more dramatic resurgences in market value, Leslie's works consistently command respectable prices, particularly his well-executed garden scenes featuring elegant figures.

Conclusion

George Dunlop Leslie RA remains an important figure in the landscape of Victorian art. As the son of a distinguished painter, he inherited a rich artistic tradition, which he skillfully adapted to his own sensibilities and to the tastes of his time. From his early engagement with Pre-Raphaelite ideals to his mature style characterized by idyllic depictions of English domesticity and garden scenes, Leslie created a body of work that is both charming and technically accomplished.

His paintings, often featuring graceful women and children in sunlit, flower-filled settings, captured an idealized vision of English life that resonated deeply with his contemporaries and continues to hold appeal. Alongside his prolific output as a painter, his contributions as an author and illustrator further enriched his artistic legacy. While perhaps not an innovator on the scale of some of his peers, Leslie was a master of his chosen genre, leaving behind a delightful and enduring record of Victorian grace and tranquility. His art provides a gentle counterpoint to the more dramatic or socially conscious works of the era, reminding us of the enduring human desire for beauty, harmony, and the simple pleasures of life.