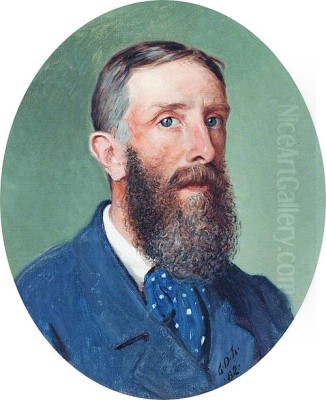

George Dunlop Leslie (1835-1921) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art, primarily celebrated for his charming and idyllic depictions of English domestic life. As a genre painter, illustrator, and writer, Leslie carved a niche for himself by capturing the serene, sunlit moments of an era often characterized by rapid industrial change and social upheaval. His work, while perhaps not revolutionary, offers a valuable window into the aspirations, aesthetics, and sentimentalities of Victorian England, particularly its burgeoning middle class. Born into an artistic dynasty, Leslie's career was marked by consistent output, academic recognition, and a gentle evolution of style that resonated with the tastes of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Lineage

George Dunlop Leslie was born in London on July 2, 1835, into a family deeply embedded in the art world. His father was the esteemed American-born Royal Academician Charles Robert Leslie (1794-1859), a painter renowned for his humorous and anecdotal scenes drawn from literature, particularly Shakespeare, Cervantes, and Molière. The elder Leslie was a friend and biographer of John Constable, another titan of British art, and his home was a hub of artistic and literary discussion. This environment undoubtedly provided young George with an unparalleled early immersion in art.

His uncle, Robert Leslie, was a notable marine painter, further cementing the family's artistic credentials. Growing up surrounded by such influences, it was almost preordained that George would follow an artistic path. He received his initial art education at Cary's Art Academy, a preparatory school for aspiring artists, before enrolling in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in 1854. This formal training would provide him with the technical grounding essential for a successful academic career. His father's connections and reputation would have also smoothed his entry into the London art scene, though his subsequent success was built on his own merits and distinct artistic vision.

The artistic atmosphere of his youth was not limited to his immediate family. His father's circle included prominent figures, and the conversations and works he was exposed to would have shaped his understanding of art's role and possibilities. This upbringing instilled in him a respect for craftsmanship and narrative clarity, elements that would become hallmarks of his own work.

The Royal Academy and Early Influences

Leslie began exhibiting at the Royal Academy in 1857, with his first painting being Hope. He continued to exhibit there annually for the rest of his career, a testament to his consistent productivity and acceptance within the establishment. His early works, created in the late 1850s and early 1860s, show the distinct influence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). Founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the PRB advocated for a return to the detailed realism, intense colour, and complex compositions of early Renaissance art, before Raphael.

Works such as Leslie's Mathilda (1860) reflect this Pre-Raphaelite sensibility, with its attention to detail, literary inspiration, and somewhat medievalizing costume. The clarity of light and the meticulous rendering of textures are characteristic of the PRB's approach. However, Leslie's engagement with Pre-Raphaelitism was perhaps more aesthetic than ideological. He adopted their bright palette and detailed finish but generally eschewed the intense moral earnestness or the more overt symbolism that often characterized the work of the core Pre-Raphaelites.

Other artists associated with or influenced by the PRB around this time included Ford Madox Brown, whose work ethic and detailed historical scenes were influential, and Arthur Hughes, known for his poignant and romantic Pre-Raphaelite paintings. Leslie's early style can be seen as part of a broader trend among younger artists who were captivated by the PRB's revolutionary approach to colour and naturalism, even if they did not fully subscribe to all its doctrines.

The St. John's Wood Clique

During the 1860s, Leslie became associated with a group of artists known as the St. John's Wood Clique. This informal group, which included figures like Philip Hermogenes Calderon, Henry Stacy Marks, William Frederick Yeames, George Adolphus Storey, and David Wilkie Wynfield, shared studios and often socialized together. They were known for their historical genre paintings, often with a light-hearted or anecdotal flavour, which were popular with the Victorian public.

The Clique's approach was less radical than that of the Pre-Raphaelites, leaning more towards accessible narratives and pleasing compositions. They often depicted scenes from British history or literature, imbuing them with a sense of charm and domesticity. Leslie's involvement with this group likely reinforced his inclination towards narrative clarity and appealing subject matter. While his themes were generally contemporary rather than historical, the emphasis on storytelling and engaging the viewer emotionally was a shared characteristic.

The St. John's Wood Clique represented a successful strand of Victorian art that catered to the tastes of the expanding middle-class art market. Their works were often reproduced as engravings, further popularizing their images. Leslie's art, with its focus on the "sunny side" of life, fitted well within this milieu, offering an escape from the harsher realities of industrial Britain.

Academic Recognition and Mature Style

Leslie's talent and appealing subject matter quickly brought him recognition. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1868 and became a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1876. These accolades cemented his position within the British art establishment.

As his career progressed, Leslie moved away from the more overt Pre-Raphaelite influences of his youth, developing a style that was more aligned with academic traditions, yet retaining a distinctive personal touch. His mature style is characterized by a bright, clear palette, a smooth, polished finish, and a focus on capturing the effects of sunlight. He became particularly renowned for his depictions of English domestic life, often set in idyllic gardens or charming interiors.

His subjects frequently featured young women and children, embodying Victorian ideals of innocence, beauty, and domestic virtue. Art critic John Ruskin, a powerful voice in Victorian art, praised Leslie's ability to capture the "sweet quality of English girlhood." This focus on idealized femininity and childhood was a popular theme in Victorian art, seen also in the works of artists like Kate Greenaway, though Leslie's approach was more naturalistic and less stylized than Greenaway's illustrations.

Leslie's paintings often evoke a sense of tranquility and nostalgia. He had a particular fondness for the Thames Valley, living for many years at Wallingford, Berkshire. The river, its banks, and the surrounding countryside frequently feature in his work, providing picturesque backdrops for his figures. His paintings are not grand historical statements or profound social commentaries, but rather intimate glimpses into a perceived golden age of English rural and domestic life.

Representative Works and Thematic Concerns

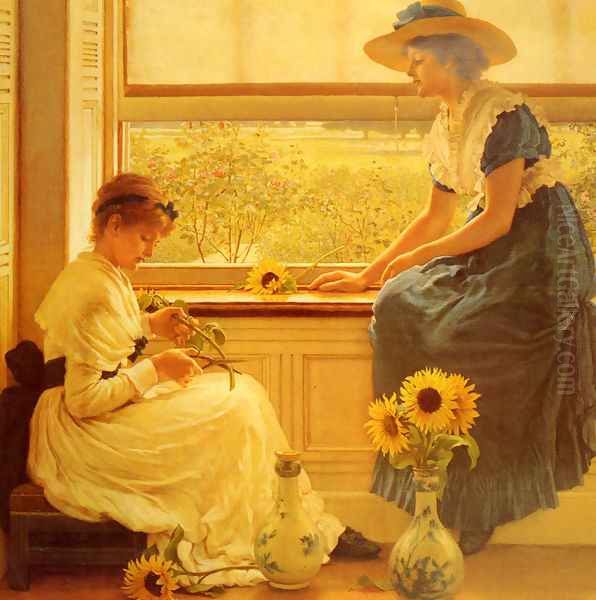

Several paintings exemplify Leslie's mature style and thematic preoccupations. Sun and Moon Flowers (1890), for instance, depicts two young women in a sun-drenched garden, tending to sunflowers and moonflowers. The painting is a symphony of light and colour, with meticulous attention paid to the rendering of the flowers and the figures' attire. It captures a moment of quiet industry and natural beauty, typical of Leslie's oeuvre.

School Revisited (1896) shows a young woman, presumably a former pupil, visiting her old schoolmistress. The scene is imbued with a gentle sentimentality, evoking themes of memory, respect, and the passage of time. The interior is depicted with Leslie's characteristic attention to detail and his skillful handling of light filtering through a window.

The Lass of Richmond Hill (exhibited 1890) takes its title from a popular song, showcasing Leslie's occasional engagement with literary or musical themes, much like his father, though in a more contemporary setting. The painting depicts an elegant young woman in a sunlit landscape, embodying the romantic ideal of the song.

Pot Pourri (1874) is another well-regarded work, showing two women in an elegant interior carefully preparing dried flower petals for potpourri. The scene is intimate and domestic, highlighting feminine accomplishments and the quiet beauty of everyday life. The rich fabrics, the delicate handling of the flowers, and the serene expressions of the figures are all characteristic of Leslie's refined style.

His painting Tea (exhibited 1885, though some sources suggest an earlier date for similar compositions) depicts a young woman in 18th-century attire preparing afternoon tea. This work highlights the Victorian fascination with historical costume and manners, as well as the enduring ritual of tea-drinking. The careful depiction of the porcelain and the play of light on the fabrics are notable.

Fortune (1870), now in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, is an earlier example that still shows some Pre-Raphaelite clarity but is moving towards his more characteristic genre scenes. It depicts a young woman by a sundial in a garden, a common motif symbolizing the passage of time and fate.

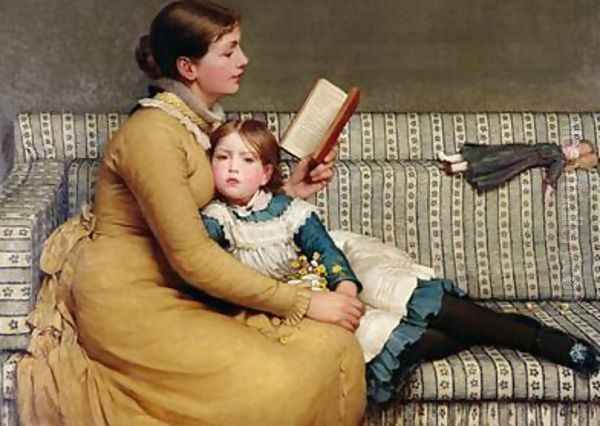

Other notable works include Daughters of Eve, The Path by the River, Roses, and The Lily Pond. Many of his paintings feature young women in gardens, often engaged in leisurely pursuits like reading, sewing, or tending flowers. These scenes resonated with Victorian ideals of domesticity and the importance of the home and garden as havens of peace and beauty. His portrayal of children was also highly praised, capturing their innocence and playful charm without excessive sentimentality.

Leslie as a Writer and Illustrator

Beyond his accomplished career as a painter, George Dunlop Leslie was also a talented writer and illustrator. His literary works often complemented his artistic interests, focusing on nature, rural life, and art history.

He published several books, including:

Our River (1881): An affectionate account of life along the Thames, illustrated with his own drawings. This book reflects his deep love for the river and its surroundings, which so often featured in his paintings.

Letters to Marco (1893): A collection of observations on nature and country life, presented as letters to his friend and fellow artist Henry Stacy Marks ("Marco").

Riverside Letters (1896): A sequel to Letters to Marco, continuing his charming reflections on the natural world.

The Inner Life of the Royal Academy (1914): A valuable historical account of the institution with which he was so closely associated, offering insights into its workings and personalities.

His illustrations, typically black and white, possess the same charm and attention to detail as his paintings. He also provided illustrations for other publications, including an edition of Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland around 1879, showcasing his versatility. His writing style was engaging and accessible, much like his paintings, appealing to a broad audience.

Artistic Connections and Contemporaries

Leslie's career spanned a dynamic period in British art. While he maintained his own distinct style, he was aware of and interacted with many leading artists of his day.

His father, Charles Robert Leslie, was a primary influence, particularly in terms of narrative painting and a gentle, often humorous, approach to subject matter.

The Pre-Raphaelites – John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti – marked his early development. Millais, in his later career, also moved towards more popular and sentimental subjects, such as Bubbles, creating a parallel, in some respects, to Leslie's appeal.

His colleagues in the St. John's Wood Clique, such as Philip Hermogenes Calderon and Henry Stacy Marks, shared a similar approach to genre painting.

Other prominent Victorian painters whose work provides context for Leslie's include:

William Powell Frith: Famous for his panoramic scenes of modern life like Derby Day and The Railway Station, Frith captured the bustling energy of Victorian society, a contrast to Leslie's more tranquil focus.

Luke Fildes: Known for his social realist paintings like Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward, Fildes tackled the darker aspects of Victorian life, a path Leslie chose not to follow. However, Fildes also painted more decorative and pleasing society portraits.

Marcus Stone: A contemporary and friend, Stone also specialized in sentimental genre scenes, often with historical or literary themes, and achieved great popularity.

James Tissot: The French painter who spent a significant part of his career in London, Tissot depicted scenes of fashionable contemporary life with a sophisticated, slightly detached eye, often focusing on the complexities of social interactions. His work shares with Leslie's an interest in contemporary costume and settings, but often with a more worldly undertone.

Frederic Leighton, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and Edward Poynter: These were the giants of High Victorian Classicism, producing large-scale, highly finished paintings of mythological or historical subjects. While their subject matter differed greatly from Leslie's, they represented the pinnacle of academic success and technical polish, an ideal to which many artists, including Leslie in his own way, aspired. Alma-Tadema, in particular, was famed for his meticulous rendering of textures like marble and fabric, a skill Leslie also demonstrated in his chosen domestic contexts.

George Frederic Watts: A more allegorical and symbolic painter, Watts aimed for a "higher" art, often with moral or spiritual messages, representing another facet of the diverse Victorian art scene.

Hubert von Herkomer: Another versatile artist, Herkomer engaged with social realism but also achieved success as a portraitist and printmaker.

Leslie's work, therefore, should be seen within this rich tapestry. He chose a specific path, focusing on the idyllic and the charming, which found a ready audience. He was not an innovator in the mould of the Impressionists, who were his contemporaries across the Channel, nor did he engage with the social critiques of some of his British peers. Instead, he perfected a vision of domestic bliss and rural beauty that offered comfort and delight.

Personal Life and Later Years

George Dunlop Leslie married Lydia Griffen, though some sources suggest an intimate, unmarried relationship with a Lydia West, with whom he had a son, Peter Leslie (1877–1953), who also became an artist. This aspect of his personal life remains somewhat private in historical records. He spent much of his life in Wallingford, Berkshire, by the Thames, which provided endless inspiration. Later, he moved to "Compton House" in Lindfield, Sussex.

He remained a consistent exhibitor and a respected member of the art community throughout his life. His work continued to be popular, though by the early 20th century, artistic tastes were beginning to shift dramatically with the advent of modernism. Movements like Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism were challenging the very foundations of academic art that Leslie represented.

Despite these changing tides, Leslie remained true to his artistic vision. He passed away on February 21, 1921, in Lindfield, Sussex, at the age of 85.

Legacy and Posthumous Reputation

In the decades following his death, as modernism became the dominant force in art, the reputation of many Victorian academic painters, including George Dunlop Leslie, declined. Their work was often dismissed as sentimental, overly narrative, or out of touch with the realities of modern life. The emphasis shifted towards formal innovation and avant-garde experimentation.

However, from the latter part of the 20th century onwards, there has been a significant reassessment of Victorian art. Art historians and the public alike have begun to appreciate the technical skill, narrative complexity, and cultural significance of painters like Leslie. His work is now seen as a valuable record of Victorian tastes and ideals, particularly the emphasis on domesticity, the beauty of nature, and a certain idealized vision of English life.

His paintings are held in numerous public collections, including the Tate Britain, the Royal Academy of Arts, the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, and various regional museums in the UK and abroad. They continue to be popular at auction, admired for their charm, technical accomplishment, and evocative portrayal of a bygone era.

While Leslie may not be counted among the great revolutionaries of art history, his contribution is nonetheless significant. He was a master of his chosen genre, creating images that brought pleasure to many during his lifetime and continue to do so today. His paintings offer a gentle, sunlit counterpoint to the often-turbulent narrative of the Victorian age, reminding us of the enduring appeal of beauty, tranquility, and the simple joys of domestic life. His writings, particularly The Inner Life of the Royal Academy, also provide important historical insights.

Conclusion

George Dunlop Leslie was an artist who perfectly captured a particular facet of the Victorian sensibility. Born into an artistic family and trained in the academic tradition, he developed a distinctive style characterized by bright colours, meticulous detail, and a focus on idyllic scenes of English domesticity and rural life. His depictions of young women, children, and sun-drenched gardens resonated deeply with his contemporaries, earning him widespread popularity and academic recognition.

As a member of the Royal Academy, a successful exhibitor, and a charming writer, Leslie played a significant role in the cultural life of his time. While his art may not have engaged with the dramatic social changes or the avant-garde artistic currents of his era, it offered a vision of harmony and beauty that was, and remains, deeply appealing. In the broader history of British art, George Dunlop Leslie stands as a skilled and sensitive chronicler of Victorian England's gentler, sunnier side, his work a lasting testament to the era's ideals of home, hearth, and the picturesque.