Phillip Richard Morris (1833-1902) stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the diverse landscape of 19th-century British art. His career spanned a period of immense artistic change and societal development, and his work reflects both the academic traditions he was schooled in and the popular tastes of the Victorian era. From grand historical and biblical narratives to tender genre scenes and, later, distinguished portraiture, Morris carved out a respectable niche for himself, leaving behind a body of work that offers insight into the artistic currents and cultural values of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in Devonport, Devon, in 1833, Phillip Richard Morris's early life was not initially set on an artistic path. His father, John S. Morris, was an iron founder and engineer, and it was expected that young Phillip might follow a similar industrial or technical trade. However, the call of art proved strong. An innate talent and a burgeoning interest in drawing and painting began to manifest, setting him apart from a purely practical career.

A pivotal figure in Morris's early artistic journey was the renowned Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt. Hunt, already an established artist and a founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, recognized Morris's potential. It was reportedly on Hunt's advice and with his encouragement that Morris was persuaded to pursue art formally, and that his father was convinced to allow his son to follow this less conventional vocation. This connection to Hunt would, in subtle ways, echo through some of Morris's approaches to detail and subject matter, even if he never fully embraced the radical tenets of Pre-Raphaelitism.

Formal Training and Academic Recognition

With this crucial support, Morris embarked on his formal artistic education. He initially studied the antique sculptures at the British Museum, a traditional starting point for aspiring artists, honing his draughtsmanship by copying classical forms. This foundational training was essential for entry into the prestigious Royal Academy Schools, which he successfully joined in 1855. The Royal Academy was the dominant institution in the British art world, shaping artistic standards and providing a vital platform for exhibition and patronage.

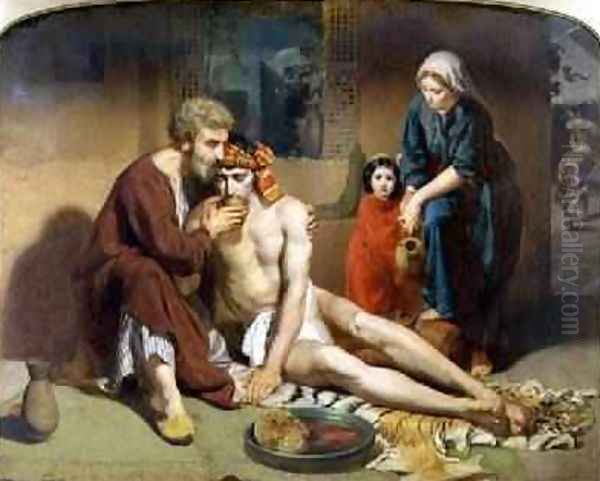

At the Royal Academy Schools, Morris proved to be a diligent and talented student. His dedication culminated in a significant early achievement: in 1858, he was awarded the Gold Medal for his historical painting, The Good Samaritan. This was a highly coveted prize, and it came with a travelling scholarship. This scholarship enabled Morris to journey to Italy and France, an experience considered vital for an artist's development. Exposure to the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance and the contemporary art scenes in continental Europe would undoubtedly have broadened his artistic horizons and refined his technique.

Themes and Subjects: A Versatile Painter

Phillip Richard Morris's oeuvre is characterized by its thematic diversity, showcasing his ability to adapt his skills to various popular genres of the Victorian era. He did not confine himself to a single specialty, which speaks to both his versatility and perhaps the market demands of the time.

Biblical and Historical Narratives

Following his early success with The Good Samaritan, Morris continued to produce paintings with biblical and historical themes. These subjects were highly regarded within the academic tradition and appealed to the Victorian public's appetite for moral instruction and grand narratives. Works such as Christ Walking on the Water exemplify this aspect of his output. These paintings often required careful composition, dramatic lighting, and an ability to convey profound human emotions, skills honed during his academic training. The influence of painters like Benjamin West or even the grand manner of Sir Joshua Reynolds, though from an earlier generation, still informed the expectations for such works.

Genre Scenes and the Poetry of Everyday Life

Alongside these more imposing subjects, Morris excelled in genre painting, capturing scenes of everyday life, often imbued with a gentle sentimentality that resonated deeply with Victorian audiences. Works like The Swing, Foster Sisters, and The Return of the Highland Laddie fall into this category. These paintings often depicted rural life, childhood innocence, or domestic affections. They were less about grand historical events and more about the relatable, intimate moments of human experience.

His genre scenes often featured children, a popular subject in Victorian art, reflecting contemporary ideals about childhood and family. The portrayal of tranquil rural settings, perhaps a nostalgic nod to a pre-industrial idyll, also found favor. In this, he shared thematic territory with contemporaries like Thomas Faed, who specialized in Scottish genre scenes, or Frederick Daniel Hardy and the Cranbrook Colony, known for their detailed domestic interiors.

Maritime and Coastal Themes

Morris also demonstrated an affinity for maritime and coastal subjects. The sea held a powerful sway over the Victorian imagination, representing Britain's imperial power, a source of livelihood, and a realm of natural beauty and peril. His paintings in this vein often captured the atmospheric qualities of the coast, the lives of fishing communities, or the poignant drama of events at sea. These works allowed for a different kind of realism, focusing on natural elements and the human relationship with the environment, perhaps echoing the landscape traditions of artists like J.M.W. Turner in their atmospheric effects, albeit on a more intimate scale.

The Shift to Portraiture

In his later career, Morris increasingly turned his attention to portraiture. This was a common trajectory for many successful artists, as portrait commissions provided a steady income and an opportunity to engage with prominent members of society. His skill in capturing a likeness, combined with his academic training in rendering form and texture, made him a competent portraitist. While perhaps not reaching the fashionable heights of a John Singer Sargent or the psychological depth of a G.F. Watts in portraiture, Morris produced solid, characterful likenesses that satisfied his patrons.

Artistic Style: Detail, Sentiment, and Light

Phillip Richard Morris's artistic style can be characterized by a blend of academic polish and a sensitivity to the emotional content of his subjects. He was proficient in various media, including oil painting and watercolor, and also engaged in engraving and printmaking, demonstrating a broad technical skillset.

His paintings often exhibit a careful attention to detail, a hallmark of much Victorian art, possibly reinforced by his early association with William Holman Hunt and the Pre-Raphaelite emphasis on "truth to nature." However, Morris's realism was generally softer and less intensely symbolic than that of the core Pre-Raphaelites like Hunt, John Everett Millais, or Dante Gabriel Rossetti. His figures are solidly rendered, and their settings are depicted with a concern for accuracy, but the overall effect is often one of gentle observation rather than didactic intensity.

A notable characteristic of many of his works, particularly his genre scenes, is a sense of tranquility and peace. He often depicted scenes bathed in a soft, warm light, contributing to a feeling of serenity. Whether portraying children at play in a sun-dappled forest, a quiet coastal scene, or a tender domestic moment, Morris aimed to evoke a sense of calm and often gentle nostalgia. This contrasts with the more dramatic or socially critical realism of some of his contemporaries, such as Luke Fildes or Hubert von Herkomer in their depictions of poverty and social hardship.

While influenced by Hunt, Morris developed his own distinct artistic voice. He did not fully adopt the vibrant, jewel-like palette of the early Pre-Raphaelites, nor their complex iconographical schemes. Instead, his originality lay in his ability to synthesize academic technique with popular sentiment, creating works that were accessible, pleasing, and emotionally resonant for his audience.

Morris in the Victorian Art World: Contemporaries and Context

To fully appreciate Phillip Richard Morris, it's essential to place him within the bustling and competitive art world of Victorian Britain. The Royal Academy of Arts, where he trained, exhibited, and later taught, was the central institution. Election as an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA), which Morris achieved in 1877, was a significant mark of peer recognition, though he never attained full Academician (RA) status.

He exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy from 1858 until 1901, a remarkably long and consistent presence. His contemporaries exhibiting at the RA included some of the titans of Victorian art. Figures like Frederic, Lord Leighton, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and Sir Edward Poynter dominated the classical and historical genres with their polished, archaeologically informed canvases. Morris's historical and biblical works would have been seen alongside theirs, though perhaps without their sheer scale or opulent detail.

In the realm of genre painting, he shared exhibition space with artists like William Powell Frith, whose panoramic depictions of modern life such as Derby Day or The Railway Station were immensely popular. While Morris's genre scenes were typically more intimate and less overtly narrative than Frith's, they tapped into a similar public interest in scenes of everyday existence.

The legacy of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood continued to exert influence. While Morris was a friend of Hunt, his style diverged from the intense naturalism and symbolic depth of Hunt, Millais (in his PRB phase), or Rossetti. He was perhaps closer in spirit to later artists who adopted a softened Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic, focusing on beauty and sentiment, such as Arthur Hughes or John William Waterhouse, though Waterhouse's subjects often veered more towards mythological and literary romance.

The period also saw the rise of the Aesthetic Movement, with artists like James McNeill Whistler and Albert Moore championing "art for art's sake," prioritizing formal qualities and beauty over narrative or moral content. Morris's work, with its clear storytelling and emotional appeal, remained more aligned with mainstream Victorian tastes than with the avant-garde tendencies of Aestheticism.

His landscape and coastal scenes can be seen in the context of a strong British tradition of landscape painting, though by the mid-to-late Victorian era, the dramatic Romanticism of Turner or the detailed naturalism of John Constable had given way to a variety of approaches, including the more atmospheric and mood-driven landscapes of artists like Benjamin Williams Leader.

A Note on a Curious Coincidence: The "Other" Richard Morris

It is worth noting a point of potential confusion that sometimes arises due to a similarity in names. Historical records mention a "Richard Morris" associated with a book titled The Last Legacy of Richard Morris, the Country Conjuror, which dealt with themes of superstition, magic, and divination. This Richard Morris, the conjuror or writer on such topics, is distinct from Phillip Richard Morris, the artist. There is no evidence to suggest that Phillip Richard Morris, the painter of biblical scenes and gentle genre subjects, had any involvement with occult practices or writings on conjuring. Such coincidences in names are not uncommon in historical records and require careful differentiation. Phillip Richard Morris's life and work firmly belong to the world of academic art and popular Victorian painting.

Later Years, Teaching, and Legacy

Phillip Richard Morris continued to be an active figure in the art world into his later years. His election as an ARA in 1877 solidified his professional standing. In 1900, towards the end of his career, he took on the role of a teacher at the Royal Academy Schools, passing on his knowledge and experience to a new generation of artists. This appointment reflects the respect he commanded within the institution that had been central to his own development.

His output may have lessened in his final years, as is common with many artists, but his commitment to his profession remained. He passed away in 1902 in London, leaving behind a significant body of work that had found favor with the public and critics during his lifetime.

Today, Phillip Richard Morris may not be as widely celebrated as some of his more famous contemporaries like Leighton, Millais, or Whistler. However, his paintings are held in various public collections and continue to appear on the art market, appreciated for their technical skill, charming subject matter, and their embodiment of Victorian sensibilities. His work provides valuable insight into the tastes and values of the era, reflecting a desire for art that was both morally uplifting and emotionally engaging. He successfully navigated the demands of academic tradition and popular appeal, creating a career that, while perhaps not revolutionary, was certainly accomplished and respected. His paintings of serene landscapes, touching domestic scenes, and dignified portraits offer a window into the heart of Victorian Britain.