George Engleheart stands as one of the most accomplished and prolific miniature painters of the late 18th and early 19th centuries in England. Flourishing during the golden age of the art form, his work is celebrated for its technical brilliance, distinctive style, and sensitive portrayal of his sitters. Appointed Miniature Painter to King George III, Engleheart enjoyed considerable success, creating thousands of portraits that captured the likenesses of the era's elite. His meticulous craftsmanship and unique aesthetic secured his place alongside the foremost artists of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Blackheath, near London, likely in 1752 (though some sources suggest 1750), George Engleheart was the son of Francis Engleheart, a plaster modeller who had emigrated from Germany. This artistic background may have influenced young George's path. Initially, his interest leaned towards landscape painting, a genre gaining popularity in England at the time.

His formal artistic training began under George Barret Sr., a respected landscape painter who had himself been a pupil of the eminent Sir Joshua Reynolds. This connection proved pivotal. Engleheart subsequently entered the studio of Reynolds, the first president of the Royal Academy and the dominant figure in British portraiture. Working in Reynolds's studio provided invaluable experience, not just in technique but also in understanding the demands of high-society portraiture.

During this period, it was common practice for aspiring artists to hone their skills by copying the works of established masters. Engleheart diligently copied paintings by Reynolds, absorbing lessons in composition, colour, and characterization. These copies were not merely exercises; they were often sold, providing income and further disseminating the master's style while showcasing the copyist's skill. This training under Reynolds profoundly shaped Engleheart's approach to portraiture, even as he adapted it to the intimate scale of the miniature.

Establishing Independence and Royal Patronage

Around 1773, Engleheart established himself as an independent artist, specializing in miniature painting. This medium, typically executed in watercolour on ivory, was highly fashionable for personal keepsakes and intimate portraits. His talent was quickly recognized, and he began exhibiting his works at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in London.

His association with the Royal Academy was long and consistent. Records show he exhibited there regularly from 1773 until 1822, a period spanning nearly five decades. This consistent presence kept his work visible to patrons, critics, and fellow artists, solidifying his reputation within the competitive London art world. His exhibits showcased his evolving skill and the breadth of his clientele.

Engleheart's career reached a significant peak when he was appointed Miniature Painter to King George III in 1789. This prestigious appointment not only brought him royal commissions but also significantly enhanced his status and appeal to the aristocracy and gentry. He shared this royal favour with his contemporary and chief rival, the flamboyant Richard Cosway, whose style was often more overtly glamorous. The contrast between Engleheart's more reserved, technically precise style and Cosway's fluid, flattering approach defined the pinnacle of English miniature painting during this era.

The Distinctive Style of George Engleheart

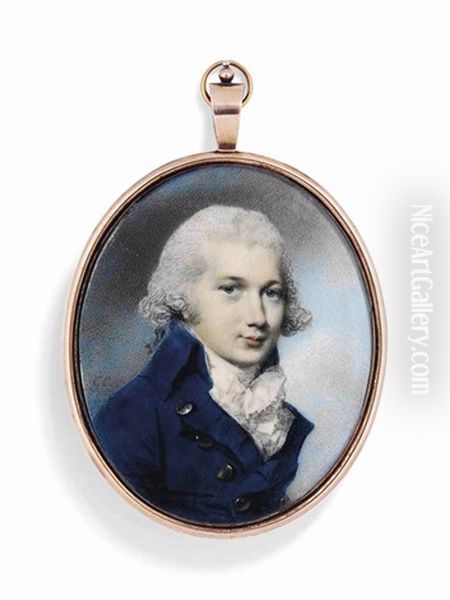

Engleheart's miniatures are renowned for their high quality and distinctive stylistic features. He typically worked on ivory, favouring its smooth, luminous surface which allowed for fine detail and subtle gradations of tone. His technique was characterized by meticulous precision and delicate, yet confident, brushwork.

His colour palette was often restrained, frequently employing cool tones dominated by blues, greys, and whites. This sometimes lent his portraits an almost monochromatic feel, reminiscent of a fine drawing or engraving, yet imbued with subtle colour harmonies. This controlled use of colour focused attention on the sitter's features and expression, rather than on elaborate costumes or settings.

Engleheart excelled at rendering the human face with sensitivity and depth. His portraits are noted for the large, expressive, and often deeply drawn eyes of his sitters, which seem to convey a sense of inner life and contemplation. He masterfully used light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to model the face, creating a strong sense of three-dimensionality despite the small scale. A characteristic feature often observed in his work is a soft, almost transparent white or pale blue halo effect around the sitter's head, subtly separating them from the background.

Unlike some contemporaries who favoured elaborate backgrounds or allegorical details, Engleheart generally preferred simplicity. Backgrounds are often plain or subtly shaded, ensuring the viewer's focus remains squarely on the portrait subject. This clarity and directness contribute to the enduring appeal of his work. He captured a sense of quiet dignity and elegance in his sitters, conveying personality through nuanced expression rather than overt gesture.

Prolific Output and Notable Works

George Engleheart was an exceptionally industrious artist. His personal fee book, meticulously maintained from 1775 to 1813, records an astonishing number of commissions – nearly 4,900 miniatures. This averages out to hundreds of portraits each year, a testament to his efficiency, popularity, and disciplined work ethic. This fee book remains an invaluable resource for art historians, providing provenance and dating for many of his works.

His sitters included members of the Royal Family, numerous aristocrats, gentry, military officers, and prominent figures of the day. While specific "masterpieces" in miniature painting are often defined by the sitter's importance or the work's condition and typicality, Engleheart maintained a remarkably high standard across his vast output.

Among the works exhibited at the Royal Academy was a fine watercolour on ivory miniature of Mary Tymewell Black, painted between 1777 and 1780. Such documented examples help scholars understand his style during specific periods. His copies after Sir Joshua Reynolds also form an important part of his oeuvre, demonstrating his connection to the leading portraitist of the age and the common practice of artistic learning and dissemination. While primarily a portraitist, some records suggest he also produced occasional landscape miniatures, harking back to his initial artistic interests.

His signature style evolved subtly over his long career. He often signed his work, typically with a cursive 'E' or 'G.E.', and frequently added the date. Variations in his signature, sometimes including a flourish or specific letter forms like an added 'e' or 's', can occasionally assist in dating his works more precisely.

Engleheart in the Georgian Art World

Engleheart operated within a vibrant and competitive art scene in Georgian London. The Royal Academy, under the presidency of Sir Joshua Reynolds and later Benjamin West, was the epicentre of this world. Exhibiting there placed Engleheart in direct dialogue and competition with the leading artists of his day.

His primary rival in the field of miniature painting was Richard Cosway, known for his fashionable, often flattering portraits and close ties to the Prince Regent (later King George IV). While both were highly successful, their styles differed: Cosway's work often featured looser brushwork and a brighter palette, while Engleheart's was generally more precise and tonally subdued.

Beyond Cosway, Engleheart's contemporaries in miniature painting included other significant talents such as John Smart, renowned for his meticulous detail and work in India; Ozias Humphry, another prominent figure who also worked in India and eventually succeeded Engleheart as Miniature Painter to the King; Samuel Shelley, known for his graceful compositions often featuring multiple figures; and the brothers Andrew Plimer and Nathaniel Plimer, both producing distinctive miniatures.

Engleheart's work should also be seen in the broader context of British portraiture dominated by giants like Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, and George Romney. While working on a much smaller scale, Engleheart addressed similar challenges of capturing likeness and status. His career also overlapped with the rise of the next generation of portraitists, such as Sir Thomas Lawrence, who would come to define the Regency style. Engleheart's adherence to careful draughtsmanship and subtle characterization provided a counterpoint to the sometimes more flamboyant trends in larger-scale oil portraiture.

Professional Practices and Personal Life

The survival of Engleheart's fee book provides rare insight into the professional life of a successful artist of the period. It details the names of his sitters, the dates of commissions, and the fees charged, offering a fascinating glimpse into his clientele and business practices. This meticulous record-keeping underscores his organized and professional approach to his career.

His productivity was legendary. To complete hundreds of miniatures annually required not only skill but also discipline and an efficient studio practice. Patrons valued his ability to capture a strong likeness with relative speed, making his services highly sought after.

Details about his personal life are less documented than his professional activities. It is known that he was married, though sources sometimes differ on the number of marriages. His artistic legacy was continued within the family by his nephew, John Cox Dillman Engleheart (1784-1862), who also became a successful miniature painter, clearly influenced by his uncle's style and technique. George Engleheart retired from active practice around 1813, though he continued to exhibit occasionally until 1822. He died in Blackheath in 1829.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

George Engleheart remains a pivotal figure in the history of British miniature painting. His vast output, technical mastery, and distinctively elegant style place him in the first rank of practitioners during the art form's zenith. While perhaps lacking the fashionable flair of his rival Richard Cosway, Engleheart's work is often praised for its psychological depth, meticulous finish, and consistent quality.

His influence extended through his nephew, John Cox Dillman Engleheart, ensuring the continuation of his stylistic approach into the mid-19th century. Today, his miniatures are highly prized by collectors and are well represented in major museums and galleries worldwide, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The characteristics that made his work popular in his lifetime continue to attract admiration: the compelling gaze of his sitters, the subtle modelling of features, the delicate precision of his brushwork, and the overall sense of refined restraint. His portraits serve as intimate windows into the society of Georgian England, capturing the likenesses of individuals from a bygone era with enduring artistry.

Conclusion

George Engleheart dedicated his long career to the demanding art of the miniature portrait. From his training under George Barret Sr. and Sir Joshua Reynolds to his decades of success as an independent artist and Miniature Painter to the King, he exemplified the highest standards of craftsmanship. His distinctive style, characterized by cool palettes, precise drawing, expressive eyes, and prolific output, secured his reputation as a leading artist of his time. Alongside contemporaries like Richard Cosway and John Smart, Engleheart defined the golden age of the English miniature, leaving behind a remarkable body of work that continues to be studied and admired for its technical brilliance and quiet elegance.