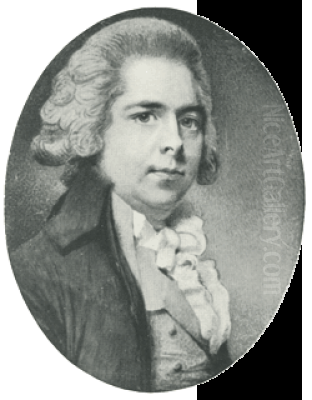

Horace Hone (1756-1825) stands as a significant figure in the annals of British and Irish art, particularly celebrated for his exquisite miniature portraits. Operating during a vibrant period for this intimate art form, Hone carved out a distinguished career, navigating the artistic currents of London and Dublin, and securing patronage from the highest echelons of society. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the cultural, social, and artistic landscapes of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in London

Born in London in 1756, Horace Hone was immersed in an artistic environment from his earliest days. He was a scion of the notable Hone family, which had strong artistic roots, particularly in Dublin. His father, Nathaniel Hone the Elder (c. 1718–1784), was a highly respected portrait painter and a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts in London. This familial connection undoubtedly provided young Horace with an invaluable early education in the principles of art and the practicalities of an artist's life. Nathaniel the Elder, known for his portraits in oil and his own accomplished miniatures, would have been a formative influence, likely instilling in his son a keen eye for likeness and a dedication to craftsmanship.

At the tender age of fourteen, in 1770, Horace Hone formally embarked on his artistic training by enrolling in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. Here, he would have honed his skills in drawing and painting, studying from casts of classical sculptures and life models, and absorbing the academic principles championed by luminaries such as the Academy's first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds. The Royal Academy, established just a few years prior in 1768, was rapidly becoming the epicenter of the British art world, and its schools offered the most comprehensive artistic education available at the time.

Hone's talent blossomed quickly. By 1772, he was already exhibiting his works at the Royal Academy's annual exhibitions, a practice he would continue with remarkable consistency for half a century. These early exhibitions were crucial for a young artist seeking to establish a reputation and attract patrons. His submissions likely included a variety of works, showcasing his versatility, but it was in the delicate art of miniature painting that he would truly excel.

The Dublin Years: Ascendancy and Esteem

A pivotal moment in Horace Hone's career came in 1782. He received an invitation from Lady Temple, the wife of George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, 1st Marquess of Buckingham, who was then serving as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. This invitation prompted Hone to relocate to Dublin, a city with a thriving cultural scene and a wealthy aristocracy eager for portraits. Dublin, at this time, was often referred to as the "second city of the Empire," and its elite society provided ample opportunities for a skilled portraitist.

In Dublin, Hone's career flourished. His charming personality and evident skill quickly made him a favorite among the Irish nobility and gentry. He became the go-to artist for those seeking elegant and refined miniature portraits, which served not only as mementos of loved ones but also as fashionable accessories and symbols of status. His sitters included many prominent figures of Irish society, and his studio would have been a hub of activity. Artists like Hugh Douglas Hamilton, who also excelled in portraiture, particularly pastels, and Robert Home were his contemporaries in the Dublin scene, though Hone's specialization in miniatures set him apart. The demand for his work was substantial, reflecting the high esteem in which his artistry was held.

His success in Dublin was further solidified by his connection to the Royal Hibernian Academy, though its formal establishment came later. The artistic community in Dublin, while smaller than London's, was vibrant, with artists like the landscape painter Thomas Roberts and the aforementioned Hamilton contributing to its richness. Hone's presence added a distinct lustre, particularly in the specialized field of miniature painting, where he was arguably pre-eminent in Ireland during his tenure there.

Royal Appointment and Shifting Tides

Horace Hone's reputation extended beyond Ireland, reaching the highest circles in Britain. In 1795, a significant honor was bestowed upon him when he was appointed Miniature Painter to His Royal Highness, the Prince of Wales, the future King George IV. This royal appointment was a testament to his exceptional skill and the widespread recognition of his talent. The Prince of Wales was a renowned connoisseur and patron of the arts, and his endorsement would have considerably enhanced Hone's prestige and desirability as an artist. He joined a select group of artists favored by the Prince, including such celebrated miniaturists as Richard Cosway and George Engleheart, who were dominant figures in the London scene.

However, the political landscape at the turn of the century brought about changes that impacted Hone's career in Ireland. The Act of Union in 1800, which formally united the Kingdom of Ireland with the Kingdom of Great Britain, led to the dissolution of the Irish Parliament in Dublin. Consequently, many of Hone's aristocratic patrons, who had residences and political interests in Dublin, began to spend more time in London. This exodus of his primary clientele inevitably affected his business in Ireland.

Faced with a diminishing market in Dublin, Horace Hone made the pragmatic decision to relocate. In 1803, he moved back to London, the bustling metropolis and the undeniable center of the British art world. Here, he sought to re-establish his practice and compete with the leading miniaturists of the day, including the aforementioned Cosway and Engleheart, as well as other skilled practitioners like John Smart and Ozias Humphry.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Influences

Horace Hone was a versatile artist, proficient in various media including oils, watercolors, and particularly enamels, in addition to his celebrated miniatures on ivory. His style was characterized by a refined naturalism, a delicate touch, and an acute ability to capture not only a sitter's likeness but also a sense of their personality. His miniatures are noted for their subtle modeling, soft yet precise rendering of features, and often, a gentle, contemplative expression in his subjects.

The execution of a miniature painting, typically on a small oval or rectangular piece of ivory, required immense skill and patience. Artists like Hone used fine brushes to apply watercolor or gouache in tiny stipples or hatches, building up layers of color to achieve depth and luminosity. The translucent quality of the ivory base contributed to the jewel-like brilliance of these small portraits. Enamel miniatures, which involved fusing powdered glass onto a metal base through firing, were even more technically demanding and offered a remarkable permanence of color. Hone's proficiency in this challenging medium further underscores his technical mastery.

His artistic development was undoubtedly shaped by his father, Nathaniel Hone the Elder, but also by the broader artistic currents of his time. The influence of Dutch Golden Age painters, particularly the psychological depth found in the portraits of Rembrandt van Rijn, can be discerned in the introspective quality of some of Hone's work. Similarly, the robust characterization and narrative flair of British artists like William Hogarth, though working in a different scale and often with satirical intent, contributed to a tradition of incisive portraiture that Hone inherited and adapted to the intimate scale of the miniature.

In his compositions, Hone often favored a simple, direct presentation of the sitter, focusing attention on the face and expression. Backgrounds were typically understated, often a soft wash of color or a suggestion of sky, ensuring that the portrait itself remained the primary focus. His depiction of costume and hair was always meticulous, reflecting the fashions of the period with elegance and precision.

Notable Works and the Social Significance of Miniatures

While it is challenging to pinpoint a single "most famous" work for an artist who produced a prolific number of commissioned portraits, certain pieces exemplify his skill. One such example often cited is a "Double portrait miniature of Irish nobility," which showcases his ability to handle complex compositions within the small format and to convey the relationship between sitters. His portraits of figures like Lady Temple or members of prominent Irish families would have been highly prized. Many of his works are now held in prestigious collections, including the National Gallery of Ireland and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, allowing contemporary audiences to appreciate his artistry.

Miniature portraits played a crucial social role in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Before the advent of photography, they were the most personal and portable way to possess a likeness of a loved one. They were exchanged as tokens of affection, carried by soldiers and sailors on campaigns, set into jewelry like lockets, bracelets, or snuffbox lids, and displayed in intimate domestic settings. For an artist like Hone, creating these small treasures was not just an artistic endeavor but also a service that connected people and preserved memories. His sitters ranged from aristocrats and military officers to fashionable ladies and their children, each portrait a unique testament to an individual life.

The demand for miniatures was immense, and artists like Hone, Richard Cosway, George Engleheart, John Smart, Samuel Shelley, and Andrew Plimer catered to this fashion. Each had their own stylistic nuances, with Cosway known for his flamboyant elegance, Engleheart for his delicate precision, and Smart for his robust characterizations, often from his time in India. Hone's work, while perhaps less overtly showy than Cosway's, possessed a quiet charm and psychological acuity that appealed to a discerning clientele.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Horace Hone operated within a rich and competitive artistic environment. In London, the Royal Academy, under the presidency of Sir Joshua Reynolds and later Benjamin West, was the dominant institution. Reynolds, along with his great rival Thomas Gainsborough, set the standard for grand portraiture. While Hone specialized in a different scale, the prevailing aesthetic ideals of elegance, naturalism, and character portrayal influenced all branches of portraiture.

In Ireland, alongside Hugh Douglas Hamilton, other notable artists included Robert Hunter and the American-born Gilbert Stuart, who spent a period working in Dublin and significantly influenced Irish portraiture. The landscape tradition was also strong, with artists like George Barret (another founding member of the RA, who had Irish origins) and later, William Ashford.

The world of miniature painting itself was a specialized and highly skilled field. The technical demands were considerable, and successful miniaturists like Hone were masters of their craft. They often had to work closely with jewelers and case makers who created the elaborate settings for their works. The intimacy of the miniature also meant that the relationship between artist and sitter could be quite personal, requiring social grace as well as artistic talent.

Anecdotes and Personal Life

Details about Horace Hone's personal life are somewhat scarcer than those of his public career, but some fragments provide insight. He married in 1779, and his will reportedly mentioned leaving a miniature portrait to his wife, a poignant reflection of his life's work. He also retained a life interest in a house in Dublin, suggesting his enduring connection to the city where he had achieved so much success.

An interesting anecdote from 1782, early in his Dublin period, recounts a critic's harsh assessment of one of his miniatures exhibited at the Royal Academy, deeming it "not worthy of exhibition." Such criticisms, while potentially disheartening, were not uncommon in the often-acerbic world of art commentary. That Hone continued to exhibit for decades and achieve such prominence suggests a resilient character and an unwavering belief in his own abilities. Indeed, the very fact that he exhibited at the Royal Academy for fifty years is a testament to his sustained productivity and his commitment to engaging with the principal artistic forum of his day.

Later Years, Legacy, and Conclusion

Despite his artistic successes, Horace Hone's later years were reportedly clouded by mental health issues. This unfortunate decline would have undoubtedly impacted his ability to work and engage with the art world as he once had. He passed away in London in 1825, at the age of 69.

Horace Hone left behind a significant body of work that marks him as one of the leading miniaturists of his generation. His career spanned a period often described as the "golden age" of British and Irish miniature painting, an era that saw this art form reach its zenith of popularity and artistic refinement before the rise of photography in the mid-19th century began to supplant its role.

His contributions were manifold: he brought a high level of skill and sensitivity to his portraits, capturing the likenesses of many important figures of his time. His work in Dublin was particularly significant, as he catered to the Irish aristocracy and contributed to the city's vibrant cultural life. The royal appointment further cemented his status as an artist of national importance.

Today, Horace Hone's miniatures are valued not only for their artistic merit – their delicate execution, pleasing aesthetics, and insightful characterization – but also as historical documents. They provide us with intimate glimpses into the faces and personalities of the people who shaped the society of late Georgian Britain and Ireland. His legacy endures in the collections of major museums and in the enduring appeal of his finely wrought portraits, which continue to speak to us across the centuries with a quiet elegance and profound humanity. He remains a distinguished figure, a master of the miniature whose art illuminated the lives of his contemporaries and continues to enrich our understanding of a fascinating period in art history. Artists like him, including his father Nathaniel Hone the Elder, and contemporaries such as Angelica Kauffman, another founding RA member, and the landscape artist Paul Sandby, all contributed to the rich tapestry of late 18th-century art.