Bernard Lens III stands as a pivotal figure in the annals of British art, particularly celebrated for his mastery in the delicate art of miniature painting during the early to mid-18th century. His contributions were not merely in the exquisite quality of his work but also in his innovative adoption of ivory as a painting surface, a technical shift that would redefine the possibilities of the medium in England.

An Artistic Lineage and Early Life

Born in London in 1682, Bernard Lens III was destined for a life in the arts. He hailed from a family already distinguished in the artistic sphere. His grandfather, Bernard Lens I (c. 1631–1708), was a painter and enameller of some note. His father, Bernard Lens II (1659–1725), was a respected mezzotint engraver, draughtsman, and drawing master. This familial environment undoubtedly provided young Bernard III with a rich artistic upbringing and early exposure to various techniques and aesthetic sensibilities.

He received his initial training from his father, absorbing the meticulous skills required for engraving and drawing. This foundational education in precision and detail would prove invaluable in his later specialization as a miniaturist. The Lens family operated a drawing school, which further immersed Bernard III in an atmosphere of artistic instruction and practice, likely bringing him into contact with a diverse range of students and artistic ideas from a young age.

The Pioneering Use of Ivory

Perhaps Bernard Lens III's most significant contribution to the history of miniature painting in Britain was his pioneering adoption of ivory as a support material. Before Lens, miniaturists in England, such as Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver in the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, and later Samuel Cooper in the 17th century, predominantly used vellum (prepared animal skin) stretched over a playing card. While vellum offered a smooth surface, it had certain limitations in terms of luminosity and the rendering of subtle flesh tones.

Around the turn of the 18th century, Italian miniaturists, most notably Rosalba Carriera, began popularizing the use of thin sheets of ivory. Ivory offered a warmer, more luminous ground that allowed for greater translucency in the watercolour washes, resulting in more lifelike and vibrant portraits. The inherent glow of the ivory itself could be cleverly incorporated into the depiction of skin, lending a natural radiance to the sitter's complexion.

Bernard Lens III is widely credited as being the first, or among the very first, English artists to embrace this new technique, likely around 1707 or 1708. This innovation was transformative. It allowed him to achieve a delicacy and subtlety in his portraits that was difficult on vellum. The smooth, non-absorbent surface of ivory enabled finer brushwork and more nuanced blending of colours, enhancing the realism and refinement of his miniatures. This technical advancement set a new standard and was quickly adopted by subsequent generations of British miniaturists, paving the way for the golden age of the English miniature in the later 18th century with artists like Richard Cosway, John Smart, and George Engleheart.

Artistic Style and Subject Matter

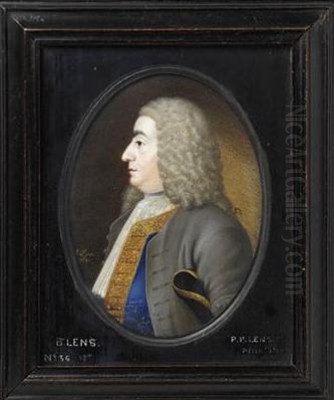

Bernard Lens III's style is characterized by its meticulous detail, refined draughtsmanship, and a delicate yet confident application of colour. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture a sitter's likeness with accuracy and sensitivity, often imbuing his portraits with a gentle, introspective quality. His rendering of fabrics, lace, and jewellery was particularly adept, showcasing his keen eye for texture and detail.

While he produced original portrait miniatures of his contemporaries, a significant portion of Lens III's oeuvre consisted of miniature copies after Old Master paintings and portraits by renowned artists. This practice was common at the time, as patrons desired smaller, portable versions of famous artworks or family portraits by celebrated painters. Lens III excelled in this genre, faithfully translating the compositions, colours, and spirit of larger oil paintings into the intimate scale of the miniature.

His palette was typically soft and harmonious, with a skilled use of stippling and hatching to model forms and create subtle gradations of tone. The use of ivory allowed him to exploit the inherent warmth of the material, particularly in rendering flesh tones, which appear luminous and natural in his best works.

Master of the Copy

Lens III's reputation as a copyist was formidable. He was frequently commissioned to create miniature versions of works by celebrated masters such as Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Nicolas Poussin. These copies were not mere slavish imitations; they required immense skill to translate the scale, medium, and painterly effects of large oil paintings into the precise and delicate language of watercolour on ivory.

One notable example is his miniature copy of Rubens, His Wife Helena Fourment, and Their Son Frans (1721), now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. This work demonstrates his ability to capture the complex figural group, rich colours, and dynamic composition of Rubens's original on a small scale. Similarly, his copy of Nicolas Poussin’s Virtue and Pleasure (1719) showcases his versatility in adapting different artistic styles.

These copies were highly prized by collectors and served various purposes. They allowed patrons to possess a version of a famous work, to complete a series of family portraits in a uniform format, or to have a portable memento of a beloved painting. Lens III's skill in this area was such that his copies were considered works of art in their own right, valued for their fidelity and exquisite craftsmanship.

Royal Appointments and Esteemed Patronage

Bernard Lens III's talent did not go unnoticed by the highest echelons of society. In 1723, he was appointed Limner (miniature painter) to King George I, a prestigious position that underscored his standing as the leading miniaturist of his day. He continued in this role under King George II. His royal patrons included not only the monarchs themselves but also other members of the royal family, such as Queen Caroline, Frederick, Prince of Wales, Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, and the Princesses Mary and Louisa.

Beyond the royal court, Lens III enjoyed the patronage of prominent aristocratic families. He was commissioned by John Hervey, 1st Earl of Bristol, to create a series of miniature copies of portraits of famous artists. He also worked for James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos, advising on his collection and undertaking commissions. The Duke of Marlborough and his wife, Sarah Churchill, were also among his distinguished clients, for whom he painted several miniatures.

His account book, which survives for the period 1718-1723, provides valuable insights into his clientele and the types of commissions he undertook. It lists numerous sitters from noble and gentry families, indicating a thriving practice. The demand for his work, both original portraits and copies, reflects the fashion for miniatures as intimate tokens of affection, status symbols, and portable works of art.

A Respected Teacher and Colleague

Like his father and grandfather, Bernard Lens III was also active as a drawing master. Teaching was an important part of the Lens family's artistic practice and a means of disseminating their skills and knowledge. Among his most famous pupils was Horace Walpole, the writer, art historian, and connoisseur, who later became a key chronicler of English art in his Anecdotes of Painting in England. Walpole's tutelage under Lens III highlights the latter's reputation as a skilled instructor.

Lens III was also an active member of London's burgeoning artistic community. He was associated with the Rose and Crown Club (or "Club of St Luke"), a convivial society of artists, collectors, and connoisseurs that met regularly in London. This club, whose members included prominent figures such as William Hogarth, George Vertue (the engraver and antiquary whose notebooks are a vital source for art historians), and the architect James Gibbs, provided a forum for discussion, networking, and the exchange of ideas. His involvement in such circles indicates his respected position among his peers. Other artists active in London during this period, whose paths he may have crossed or whose work he would have known, include the portraitists Sir Godfrey Kneller (who dominated British portraiture until his death in 1723), Michael Dahl, Jonathan Richardson, and the landscape painter Peter Tillemans.

His relationship with fellow artist Joseph Goupy is also noteworthy. Goupy, also a miniaturist and copyist, as well as a scene painter and etcher, was a contemporary and friend. Sometimes, there has been confusion between Bernard Lens III and Joseph Goupy, or an erroneous conflation of their names, but they were distinct artists who both contributed to the vibrant art scene of early 18th-century London.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

The London in which Bernard Lens III flourished was a city experiencing significant cultural and artistic growth. While the grand manner of portraiture was dominated by figures like Kneller and later by artists such as Thomas Hudson and Allan Ramsay, there was a strong and enduring market for miniatures. Lens III operated in a field that included other miniaturists, though he was preeminent among the native-born practitioners of his generation.

Foreign artists, like the Swedish-born Charles Boit, who worked in enamel, and later, Christian Friedrich Zincke, also from Germany and working in enamel, were significant figures in the London miniature scene. Enamel miniatures, fired on copper, offered a different aesthetic and durability compared to watercolours on ivory or vellum. Lens III's work in watercolour on ivory provided a softer, more painterly alternative that gained immense popularity.

The culture of copying, in which Lens III excelled, was widespread. Artists like Jean-Baptiste van Loo, a French portraitist who worked in England for a period, also had their works copied in miniature. The demand for such reproductions was fueled by the Grand Tour, which exposed wealthy Britons to Continental art, and by the desire to assemble collections that reflected taste and learning.

Lens III's innovation with ivory occurred at a time when English art was beginning to assert its own identity. While still influenced by Continental trends, native artists like Hogarth were forging new paths. Lens III's contribution, though in a more traditional genre, was significant in elevating the technical standards and aesthetic appeal of English miniature painting.

Critical Reception and Legacy

Bernard Lens III was highly regarded in his lifetime, as evidenced by his royal appointments and extensive patronage. George Vertue praised him as an "ingenious Lymner" and noted his skill in copying. Horace Walpole, his former pupil, also acknowledged his abilities, though with some reservations typical of Walpole's often critical tone, he sometimes found Lens's work a little stiff compared to the earlier masters like Isaac Oliver or Samuel Cooper. However, Walpole did commend his copies and his role as a teacher.

Later art historians have consistently recognized Lens III's importance. Dudley Heath, in his early 20th-century study of miniatures, and Graham Reynolds, in his authoritative works on English portrait miniatures, both affirm Lens's pioneering role in the use of ivory and his position as a leading miniaturist of his time. He is seen as a crucial transitional figure, linking the vellum tradition of the 17th century to the ivory-based flourishing of the later 18th century.

His works are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Royal Collection. The survival of a considerable body of his work, including signed and dated pieces, allows for a thorough appreciation of his style and development.

While some critics might have found his original compositions less spirited than those of some of his predecessors or successors, his technical proficiency, particularly in the delicate handling of watercolour on ivory and his faithful rendering of Old Masters, remains undisputed. He was described by some contemporaries as an "unrivalled watercolourist."

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Beyond the previously mentioned copy of Rubens's family, several other works highlight Bernard Lens III's skill and typical output:

Portrait of a Lady (circa 1720-1730): Many such portraits exist, often unidentified. They typically showcase his delicate flesh tones, meticulous rendering of lace and costume, and the characteristic soft blue or grey backgrounds.

Portrait of King George I / King George II: As royal limner, he would have produced multiple images of the monarchs, often based on larger state portraits by court painters like Kneller. These would have been used for diplomatic gifts or for members of the royal household.

Copies after Van Dyck: Van Dyck's elegant portraits of the English aristocracy were immensely popular, and Lens III produced numerous miniature copies after his works, capturing the refined air of the originals.

Self-Portrait (if extant and identified): Like many artists, Lens may have painted self-portraits, which would offer a direct insight into his own likeness as he wished to be perceived.

Portraits of the Duke of Cumberland: As a royal child and later a military figure, the Duke was a frequent subject for portraitists, and Lens III contributed to this iconography.

His works often bear his monogram "BL," sometimes in a cursive script, and are frequently dated, aiding in their attribution and chronological study.

Conclusion: An Enduring Influence

Bernard Lens III died in Knightsbridge, London, on April 2, 1740. He left behind a significant legacy as an artist and innovator. His adoption of ivory as a painting surface was a watershed moment for English miniature painting, enabling a new level of luminosity, delicacy, and realism. This technical advancement, combined with his own considerable skill as a draughtsman and colourist, set the stage for the great masters of the English miniature who followed him, such as Jeremiah Meyer, Richard Crosse, Richard Cosway, John Smart, Ozias Humphry, and George Engleheart.

As a royal limner, a respected teacher, a master copyist, and a prominent member of London's artistic community, Bernard Lens III played a crucial role in the development of British art in the early 18th century. His meticulous and refined miniatures remain a testament to his talent and an important part of Britain's rich artistic heritage, bridging the gap between earlier traditions and the subsequent golden age of the art form he helped to redefine. His influence extended through his pupils and through the widespread adoption of the techniques he championed, ensuring his place as a key figure in the history of miniature painting.