George Henry Hall (1825-1913) stands as a significant figure in nineteenth-century American art, celebrated primarily for his exquisite still-life paintings. While also adept at landscapes and genre scenes, it was his vibrant and meticulously detailed depictions of fruit, flowers, and vegetables that secured his reputation. Working during a period of burgeoning national identity and artistic development in the United States, Hall carved a distinct niche for himself, blending American sensibilities with European training and influences, particularly the ideals of truth to nature championed by the British critic John Ruskin.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Manchester, New Hampshire, in 1825, George Henry Hall spent his formative years in nearby Boston, Massachusetts. This bustling city, a growing cultural center, provided the backdrop for his initial artistic explorations. Unlike many of his contemporaries who sought formal academic training early on, Hall largely embarked on his artistic journey as a self-taught painter. His innate talent, however, quickly became apparent.

By the mid-1840s, Hall was already exhibiting his work. The prestigious Boston Athenaeum, a vital institution for the city's artistic life, showcased his paintings regularly between 1846 and 1868, a period spanning over two decades. This early exposure provided crucial validation and helped establish his presence within the local art community. It was during these formative years in Boston that he likely honed his observational skills and developed the foundational techniques that would later define his mature style.

European Sojourns and Influences

Recognizing the need for broader exposure and more refined training, Hall, like many ambitious American artists of his generation, looked towards Europe. In 1849, he undertook his first significant trip abroad. A key figure in facilitating this journey was the slightly older painter Eastman Johnson (1824-1906), who was also working in Boston at the time, reportedly renting a studio in the same building as Hall. Johnson's encouragement and perhaps practical advice were instrumental in Hall's decision to travel.

Hall initially headed to Düsseldorf, Germany, a major center for academic art training that attracted numerous American painters, including Albert Bierstadt, Worthington Whittredge, and Emanuel Leutze. He studied there, associating with Eastman Johnson who was also present. However, Hall reportedly grew disillusioned with the prevailing German academic style, perhaps finding its emphasis on historical or narrative subjects and its precise, somewhat rigid technique less suited to his temperament than the direct study of nature.

His European studies did not end in Germany. Hall continued his travels, spending time in Paris and Rome. These cities offered different artistic environments – Paris, a hub of emerging realism and avant-garde ideas, and Rome, steeped in classical tradition and Renaissance masterpieces. This exposure to diverse artistic currents broadened his perspective. He eventually developed a strong affinity for the cultures of the Mediterranean, particularly Spain and Italy, which would later inspire his genre paintings.

Crucially, during his time abroad and throughout his career, Hall absorbed the influence of the British art critic John Ruskin (1819-1900). Ruskin's influential doctrine of "truth to nature," which advocated for intense observation and fidelity in representing the natural world, resonated deeply with Hall. This philosophy, closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in England (though Hall was not formally part of that movement), guided his approach, especially in his still-life compositions. He sought to capture the specific textures, colors, and forms of his subjects with utmost accuracy.

Mastery of Still Life

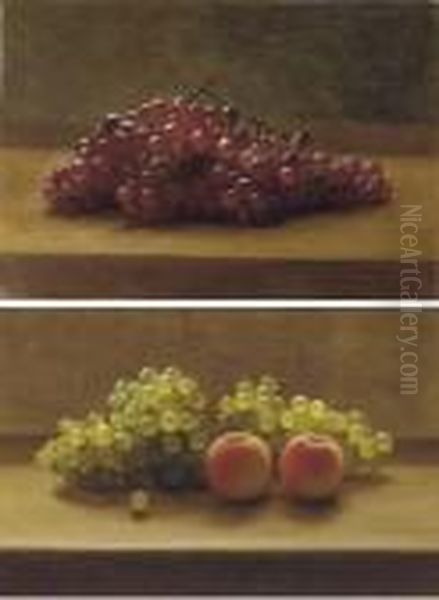

George Henry Hall's most enduring legacy lies in his mastery of still-life painting. He specialized in depicting fruits, flowers, and sometimes vegetables, often presented in simple, focused compositions. His works are characterized by their luminous color, meticulous detail, and remarkable sense of realism. He rendered the velvety skin of a peach, the translucent glow of grapes, the delicate structure of flower petals, and the crispness of leaves with extraordinary skill.

Unlike the more complex, allegorical still lifes of the Dutch Golden Age or the highly structured arrangements of some earlier American painters like Raphaelle Peale (1774-1825), Hall often presented his subjects straightforwardly, sometimes against a neutral background or situated within a suggestion of a natural setting, like a mossy bank or a simple tabletop. This directness allowed the inherent beauty and specific character of the objects themselves to take center stage.

His commitment to "truth to nature" is evident in the botanical accuracy of his floral depictions and the convincing textures of his fruits. Works like Raspberries on a Leaf or Peaches on a Plate showcase his ability to capture not just the appearance but also the tactile quality of his subjects. Viewers can almost feel the softness of the berries or the fuzz on the peaches. This intense realism appealed greatly to Victorian sensibilities, which valued detailed observation and the appreciation of nature's bounty. Hall's still lifes became highly sought after, and he successfully used the sale of these popular works to fund his extensive travels.

Beyond Still Life: Landscapes and Genre Scenes

While best known for still life, Hall's artistic output was not confined to that genre. His travels, particularly in Europe, provided rich material for other types of paintings. He spent considerable time in Spain and Italy, and later even traveled to Egypt. These experiences fueled his interest in landscape and genre subjects, capturing the picturesque aspects of foreign lands and cultures.

He painted scenes of daily life, often featuring peasants or local inhabitants in traditional attire, set against architectural backdrops or scenic landscapes. Works like A Group of Spanish Children or studies of Roman peasants reflect this interest. These paintings often possess a romantic quality, characteristic of much 19th-century art that focused on the perceived charm and exoticism of European folk life. They demonstrate his versatility as an artist and his ability to apply his keen observational skills to different subjects.

His landscapes, though less numerous than his still lifes, also show his dedication to capturing specific effects of light and atmosphere. Whether depicting the Italian countryside or scenes closer to home, he brought a sensitivity to place that complemented his detailed approach to objects.

Professional Recognition and Affiliations

George Henry Hall achieved significant recognition within the American art establishment during his lifetime. His long exhibition record began early at the Boston Athenaeum and continued at major national venues. He started submitting works to the American Art-Union in 1853 and exhibited frequently at the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia from the same year onwards.

His association with the National Academy of Design (NAD) in New York City was particularly important. Founded in 1825, the NAD was the premier art institution in the country, and election to its ranks was a mark of high professional standing. Hall was elected an Associate Member (ANA) in 1853 and achieved the status of full Academician (NA) in 1868. He exhibited regularly at the NAD's annual exhibitions for decades, placing his work before a wide audience of critics, collectors, and fellow artists.

Hall was also active in other organizations, including the Brooklyn Art Association (from 1861) and the Boston Art Club. His work was even shown internationally, including at the Royal Academy in London. Furthermore, he was a long-standing member of the Century Association in New York City, joining in 1863 and remaining a member until his death. This private club was a vital social and intellectual hub for the city's artistic and literary elite, counting figures like painters Frederic Edwin Church, Sanford Robinson Gifford, and Winslow Homer, as well as writers like William Cullen Bryant, among its members. Hall reportedly exhibited over 250 works on the Century's walls over the years, engaging with a community of influential peers.

Representative Works

Several paintings stand out as representative of George Henry Hall's style and subject matter.

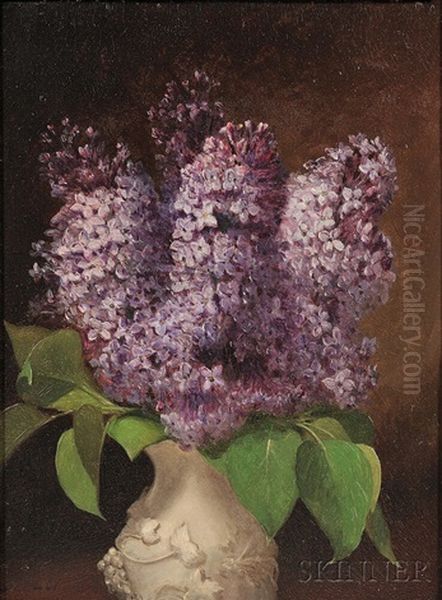

Lilacs (1872): This work exemplifies his skill in floral painting. The lush, abundant blossoms are rendered with remarkable detail, capturing the delicate structure and subtle color variations of each floret. The play of light on the petals and leaves creates a sense of vibrancy and freshness, showcasing his adherence to Ruskin's principles of close observation.

Sweet Peas: A Study from Nature (1857): An earlier floral piece, this painting highlights his ability to capture the fragility and grace of flowers. The delicate tendrils and translucent petals of the sweet peas are depicted with sensitivity, likely painted directly from life, as the title suggests.

Raspberries in a Gauntlet (c. 1860s): This is one of his more distinctive compositions, featuring ripe raspberries spilling out of a metal gauntlet (a piece of armor). The juxtaposition of the soft, perishable fruit with the hard, cold metal creates an intriguing visual and textural contrast, showcasing Hall's imaginative approach within the still-life genre.

A Dead Rabbit (1858): Painted shortly after his return from Europe, this work tackles a less conventional still-life subject, perhaps influenced by European traditions of depicting game. While demonstrating his technical skill in rendering fur and form, some have speculated it might carry deeper meanings, possibly reflecting on mortality or even subtly referencing social issues of the time, though such interpretations remain speculative. It clearly demonstrates his commitment to depicting subjects with unflinching realism.

Bric-a-Brac from Seville: This title suggests a still life composed of objects collected during his travels in Spain, reflecting his interest in exotic items and souvenirs, a common theme in Victorian decorative arts and painting. It likely combined his skill in rendering textures with a touch of the picturesque derived from his foreign experiences.

These works, among many others focusing on peaches, grapes, plums, and various flowers, illustrate the core characteristics of Hall's art: meticulous realism, rich color, sensitivity to texture and light, and a deep appreciation for the beauty found in nature's details.

Relationships with Contemporaries

George Henry Hall's long career placed him in contact with numerous figures in the American art world. His early connection with Eastman Johnson was significant, providing encouragement for his crucial first trip to Europe. Although their paths diverged somewhat stylistically – Johnson became renowned for his genre scenes and later portraits – their shared experience in Düsseldorf points to the interconnectedness of American artists seeking training abroad.

A particularly notable relationship in Hall's later life was with the painter Jennie Augusta Brownscombe (1850-1936). Considerably younger than Hall, Brownscombe met him while studying in Rome. He became a mentor and close friend. For many years, they shared a summer residence and studio near Palenville in the Catskill Mountains of New York, a popular area for artists. This arrangement continued until Hall's death in 1913, suggesting a deep personal and professional bond. Brownscombe, known for her historical and genre scenes, likely benefited from Hall's experience and guidance.

Hall's membership in the Century Association also placed him in regular contact with leading figures of the Hudson River School, such as Church and Gifford, as well as prominent genre painters and sculptors. While his primary focus on still life set him apart from the grand landscape painters, they shared a common artistic environment and likely engaged in discussions about art theory and practice, including the pervasive influence of Ruskin.

His work can be situated within the broader context of American still-life painting. He followed the tradition established by the Peale family but developed a lusher, more color-focused style than, for example, the precise trompe-l'oeil works of William Michael Harnett (1848-1892) or John F. Peto (1854-1907) that became popular later in the century. His style is perhaps closer in spirit, though different in execution, to the opulent fruit arrangements of Severin Roesen (c. 1815-c. 1872), another German immigrant artist popular in mid-century America, or the flower studies of Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904), though Heade often combined his flowers with landscapes or his iconic hummingbirds. Hall's connection to Ruskin also links him conceptually to the American Pre-Raphaelites like Thomas Charles Farrer and John William Hill, who more dogmatically followed Ruskinian principles.

Later Life and Legacy

George Henry Hall remained an active painter well into his later years. He maintained studios in New York City and, during the summers, in the Catskills, continuing to produce the still lifes that were his hallmark, alongside occasional genre scenes inspired by his travels. His home and studio near Palenville, shared for a time with Jennie Brownscombe, provided access to the natural subjects he loved to paint.

He passed away in New York City in 1913 at the age of 87 or 88. He is buried in the historic Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. Intriguingly, his tombstone bears a unique epitaph, reportedly chosen by Hall himself, which is said to reflect his personality and philosophy of life, moving beyond the standard inscriptions of the era. One account mentions the phrase "He lived for the beauty and quality of life," a fitting sentiment for an artist so dedicated to capturing the beauty of the natural world.

Today, George Henry Hall is recognized as one of America's foremost still-life painters of the 19th century. His work bridged the gap between earlier, more restrained still-life traditions and the burgeoning realism of the post-Civil War era. His dedication to "truth to nature," filtered through his own distinct sensibility, resulted in paintings that are both meticulously observed and aesthetically pleasing. His works are held in the collections of major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Brooklyn Museum, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, ensuring his contribution to American art history remains accessible to future generations.

Conclusion

George Henry Hall dedicated his long artistic career to the close observation and careful rendering of the world around him, particularly the vibrant forms and colors of fruits and flowers. Influenced by European training and the ideals of John Ruskin, he developed a distinctive style of still life characterized by realism, luminosity, and meticulous detail. While also exploring landscape and genre painting, his reputation rests firmly on his mastery of still life, a genre he elevated through his technical skill and sensitivity to natural beauty. As a respected member of the National Academy of Design and the Century Association, and a friend and mentor to fellow artists, Hall played a significant role in the American art scene of his time. His paintings continue to delight viewers with their vibrant depiction of nature's bounty and stand as a testament to a career devoted to capturing truth and beauty.