Levi Wells Prentice (1851-1935) stands as a distinctive figure in American art history, celebrated primarily for his meticulously rendered still life paintings, particularly of fruit, and his earlier evocative landscapes of the Adirondack Mountains. A largely self-taught artist, Prentice developed a unique style characterized by sharp detail, vibrant color, and an almost photographic realism, often employing techniques associated with trompe l'oeil. Though perhaps not as widely known during his lifetime as some contemporaries, his work has gained significant appreciation posthumously, recognized for its technical skill and unique contribution to American realism. His journey from a farm in upstate New York to the art studios of Brooklyn reflects a dedication to capturing the beauty he observed in both the natural world and in the simple arrangements of everyday objects.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in the Adirondacks

Levi Wells Prentice was born in 1851 on a farm near Harrisburg, Lewis County, in rural upstate New York. His formative years were spent immersed in the natural environment, a factor that profoundly shaped his artistic sensibilities. The family later moved, and Prentice spent a significant portion of his youth in the Adirondack Mountain region, an area renowned for its rugged beauty and pristine wilderness. This landscape, which would later inspire the Hudson River School painters, became Prentice's first major subject.

Unlike many artists of his era who sought formal training in established academies in America or Europe, Prentice was largely self-taught. His artistic education came from personal observation, dedicated practice, and the study of influential art texts. He is known to have read and been influenced by the writings of the prominent English art critic John Ruskin, particularly works like "Modern Painters." Ruskin championed the idea of "truth to nature," urging artists to observe and depict the natural world with fidelity and detail. This principle resonated deeply with Prentice and is evident throughout his career, both in his landscapes and his later still lifes.

Around 1874, at the age of 23, Prentice formally declared himself a landscape painter. His early works focused almost exclusively on the scenery of the Adirondacks. He traveled through the region, sketching and painting the mountains, lakes, and forests that surrounded him. This period established his connection to the prevailing artistic currents of the time, particularly the Hudson River School, though he was never formally a member of that group.

The Adirondack Landscapes: Nature's Majesty and Detail

Prentice's early career was defined by his landscape paintings of the Adirondack Mountains. These works align with the general aesthetic of the Hudson River School, America's first major school of landscape painting. Artists like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand had established a tradition of depicting the American wilderness as a source of national pride and spiritual sublimity. Prentice shared their reverence for nature and their commitment to detailed representation.

His Adirondack scenes often feature panoramic views, serene lakes reflecting dramatic skies, and dense forests rendered with careful attention to botanical detail. Works such as Adirondack Mountains Landscape exemplify this phase. He captured the specific light and atmosphere of the region, often depicting tranquil, untouched wilderness. However, Prentice's landscapes sometimes possess a unique quality, occasionally incorporating elements like gnarled tree stumps or rocky outcrops rendered with a heightened sense of realism that borders on the surreal, perhaps foreshadowing the intense focus of his later still lifes.

Following Ruskin's precepts, Prentice aimed for accuracy in his depictions. His landscapes were not merely romanticized visions but were grounded in careful observation. He often included details of specific trees, rock formations, and the play of light on water, demonstrating his intimate knowledge of the environment he painted. These works convey a sense of quiet grandeur and a deep, personal connection to the Adirondack wilderness that had been his childhood home and early inspiration. His sketchbooks from this period, such as the collection Sketchbook: Views in Upstate New York, provide insight into his working methods and his dedication to capturing nature firsthand.

Relocation to Brooklyn and the Turn to Still Life

In 1883, Levi Wells Prentice made a significant life change, moving from the rural Adirondacks to the bustling urban environment of Brooklyn, New York. This move coincided with a major shift in his artistic focus. While he did not entirely abandon landscape painting, he increasingly turned his attention to still life, the genre for which he would become most famous. The reasons for this shift are not definitively documented but could involve market demands, a desire to explore new artistic challenges, or the influence of the urban art scene.

Living in Brooklyn, Prentice needed to support himself and his family. He married Emma Roseloe Sparks in 1882, and they had two children. Alongside his painting, he reportedly worked various jobs, including carpentry and possibly furniture design and decorative painting, skills that may have further honed his attention to detail and craftsmanship. He also engaged with the local art community, occasionally exhibiting his work at venues like the Brooklyn Art Association.

The transition to still life painting, particularly focusing on fruit, seems to have occurred gradually but became dominant by the early 1900s. This change marked a departure from the expansive vistas of his landscapes to the intimate, controlled world of tabletop arrangements. Yet, the core principles of his art – meticulous detail, vibrant color, and a commitment to realism – remained constant and arguably found their most potent expression in these later works.

Mastery of Still Life: The Allure of Fruit

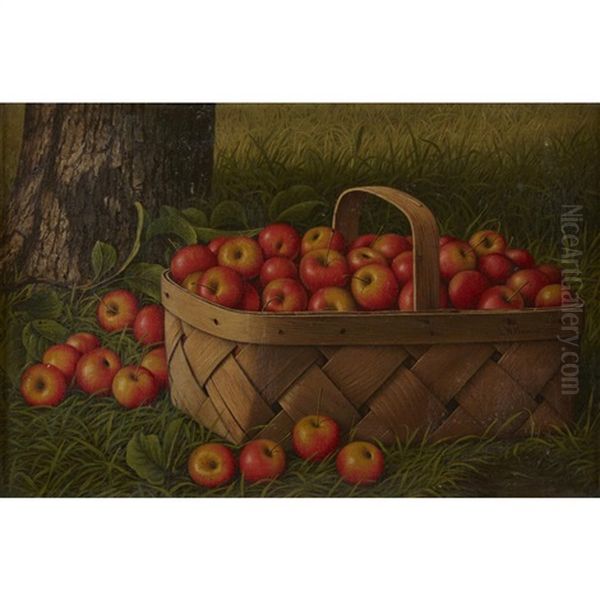

Prentice's still life paintings are what secured his lasting reputation. He developed a highly distinctive style, concentrating primarily on arrangements of fruit, especially apples, pears, peaches, plums, and berries. These works are characterized by their startling clarity, intense color, and illusionistic detail, often aligning them with the trompe l'oeil ("deceive the eye") tradition.

His compositions are often dynamic and feature fruit spilling abundantly from containers like woven baskets, overturned hats, tin pails, or even directly onto a grassy bank or a simple wooden surface. Works like Apples in a Basket (versions exist, a famous one dated 1892) or Apples by a Tree are iconic examples. The fruit itself is rendered with extraordinary precision. Each apple or pear displays individual characteristics – subtle variations in color, blemishes, the texture of the skin, and the play of light creating glossy highlights. Prentice achieved a remarkable sense of three-dimensionality, making the fruit appear almost tangible.

His technique involved using crisp, hard edges, smooth surfaces with minimal visible brushwork in the main subjects, and often a strong contrast between the brightly lit fruit and a darker, less defined background. This contrast enhances the illusion of depth and makes the fruit "pop" from the canvas. The settings are typically rustic and naturalistic, suggesting fruit freshly picked and casually arranged, often outdoors, linking back to his landscape roots and his enduring connection to nature.

Comparison with Trompe l'Oeil Masters

While Prentice's work shares characteristics with the American trompe l'oeil school, exemplified by artists like William Harnett, John F. Peto, and John Haberle, his approach was distinct. Harnett and Peto often focused on arrangements of man-made objects – books, musical instruments, currency, hunting gear – often with themes of masculinity, nostalgia, and the passage of time. Their illusionism aimed to make the viewer question the reality of the painted objects within a shallow, often shadowed space.

Prentice, while employing a similar level of hyper-realism, concentrated on natural subjects, primarily fruit. His illusionism feels less like a studio trick and more like an intensified celebration of nature's bounty. The common motif of fruit spilling out of containers suggests abundance and a connection to the harvest. Unlike the often static, meticulously arranged compositions of Harnett, Prentice's arrangements feel more dynamic and less formally posed, as if capturing a moment of natural disarray. His use of outdoor settings or simple, rustic props also differentiates his work from the more typically interior, shelf-like compositions of many trompe l'oeil specialists.

Though perhaps not strictly adhering to all conventions of the trompe l'oeil movement, Prentice's dedication to precise rendering and creating a convincing illusion places him firmly within its broader context. His unique focus on fruit within naturalistic settings carved out a specific niche for him within American still life painting.

Themes of Nature, Abundance, and Realism

Beyond the technical virtuosity, Prentice's still lifes explore several recurring themes. The most prominent is the celebration of nature's abundance. The overflowing baskets and piles of glistening fruit evoke the richness of the harvest and the fertility of the land. This imagery would have resonated in late 19th and early 20th century America, a nation still deeply connected to its agricultural roots yet rapidly industrializing.

There is often a subtle interplay between the natural and the man-made in his compositions. The perfect, organic forms of the fruit are contained or juxtaposed with objects crafted by human hands – woven baskets, tin pails, straw hats. This contrast highlights the beauty of the natural world while acknowledging human interaction with it, whether through cultivation, harvest, or simple appreciation.

Prentice's unwavering commitment to realism, inherited from his Ruskinian studies and Hudson River School influences, is central. He sought to represent the fruit not just generically, but as specific, individual entities. The viewer can almost discern the variety of apple or feel the fuzz on a peach. This intense focus elevates the humble subject matter, inviting contemplation of the beauty found in everyday natural objects. His realism is not merely photographic; it is heightened, imbued with vibrant color and dramatic light that gives the fruit an almost luminous quality.

Artistic Influences and Context Revisited

Levi Wells Prentice operated within a rich artistic landscape, absorbing influences while forging his own path. John Ruskin's emphasis on close observation of nature was a foundational element, visible in both his landscapes and still lifes. The Hudson River School provided the context for his early landscape work, sharing its reverence for the American wilderness and detailed rendering, even if Prentice maintained a degree of independence from the group's core members like Frederic Edwin Church or Albert Bierstadt, known for their monumental canvases.

His shift to still life placed him in dialogue with the American tradition of realist still life painting, which had roots stretching back to the Peale family, particularly Raphaelle Peale, in the early 19th century. The rise of trompe l'oeil in the post-Civil War era, led by Harnett, Peto, and Haberle, undoubtedly provided a more immediate context and likely influenced Prentice's pursuit of illusionistic detail.

However, Prentice remained somewhat distinct from mainstream movements. While contemporaries like Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer were exploring different facets of American Realism, often focusing on human figures and scenes of modern life, Prentice concentrated on landscape and still life. His crisp, detailed style also stood apart from the looser brushwork and atmospheric concerns of American Impressionism, which was gaining prominence during the later part of his career through artists like Childe Hassam and Mary Cassatt. Prentice's dedication to a highly finished, detailed realism aligned him more with traditional techniques, even as the intensity of his vision sometimes bordered on the surreal, hinting perhaps at later developments in 20th-century art. His work can be seen as a unique synthesis of 19th-century realist traditions.

Technique, Materials, and Working Process

Prentice primarily worked in oil on canvas. His technique, especially in the still lifes, was characterized by meticulous application of paint to achieve smooth surfaces and sharp details. He likely used fine brushes to render the textures of the fruit, the weave of baskets, and the play of light. His use of color was bold and saturated, contributing to the vibrancy and lifelike quality of his subjects. Strong contrasts between light and shadow (chiaroscuro) were essential for creating the illusion of volume and three-dimensionality.

The consistent quality and specific recurring motifs (like particular types of apples or baskets) suggest a dedicated studio practice. While his landscapes were informed by outdoor sketching, as evidenced by his sketchbooks, his still lifes were likely composed and painted in the studio, where he could control the lighting and arrangement precisely. The "spilling" compositions, while appearing casual, were carefully constructed for maximum visual impact.

His background may have included practical skills like carpentry and decorative painting, which could have influenced his precise handling of form and his understanding of materials. This hands-on experience might have contributed to the tangible quality present in his depictions of both natural and man-made objects. The overall effect is one of intense focus and deliberate craftsmanship, elevating the simple subject matter through sheer technical skill.

Later Life, Recognition, and Collections

Levi Wells Prentice continued to paint throughout his life. After his time in Brooklyn, he eventually moved to Philadelphia. He passed away in Germantown, Philadelphia, in 1935, at the age of 84. During his lifetime, while he exhibited periodically and likely sold works privately, he did not achieve the widespread fame or critical acclaim accorded to some of his contemporaries. His style, particularly the highly detailed realism of his still lifes, might have seemed somewhat conservative or specialized compared to the emerging trends of Impressionism and early Modernism.

However, interest in American realism and trompe l'oeil painting saw a resurgence in the mid-to-late 20th century, leading to a posthumous rediscovery and appreciation of Prentice's work. Art historians and collectors began to recognize the unique quality and technical brilliance of his paintings. His distinctive fruit still lifes, in particular, became highly sought after.

Today, Levi Wells Prentice's paintings are held in the collections of several major American museums, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Yale University Art Gallery; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Adirondack Museum (now Adirondack Experience, The Museum on Blue Mountain Lake); and the Museum of the City of New York, among others. His inclusion in these significant public collections affirms his importance within the history of American art. Auction records also show continued interest in his work among private collectors.

Legacy and Impact in American Art

Levi Wells Prentice occupies a unique position in American art history. He was a bridge figure, beginning his career under the influence of the Hudson River School's landscape tradition and transitioning to become a master of realist still life with strong affinities to the trompe l'oeil movement. His self-taught background underscores his personal dedication and innate talent.

His primary legacy lies in his fruit still lifes. These works stand out for their combination of meticulous realism, vibrant color, dynamic compositions, and their specific focus on fruit within rustic, often naturalistic settings. He captured the sensuous appeal of fruit – its color, texture, and form – with an intensity that few others matched. While influenced by broader trends, he developed a personal and instantly recognizable style.

Though not a direct precursor to major 20th-century movements, the heightened realism and intense focus in Prentice's work can be seen in retrospect as possessing qualities that might resonate with later styles like Magic Realism or even aspects of Surrealism, where ordinary objects are rendered with uncanny clarity. His enduring appeal lies in the directness and technical brilliance of his vision, celebrating the beauty of the natural world in both its grand vistas and its humble details. He remains a testament to the diverse paths taken by American artists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

Levi Wells Prentice was an American original. From his early, sensitive renderings of the Adirondack wilderness to his later, dazzlingly realistic fruit still lifes, his work consistently demonstrates a profound connection to nature and an extraordinary technical facility. Largely self-taught, he absorbed the influences of his time – the naturalism of Ruskin, the grandeur of the Hudson River School, the illusionism of trompe l'oeil – but synthesized them into a style uniquely his own. His paintings, particularly the iconic images of fruit spilling from baskets and hats, continue to captivate viewers with their vibrant color, meticulous detail, and celebration of natural abundance. Though his recognition came largely after his death, Levi Wells Prentice is now rightfully acknowledged as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of American realism.