George Lance stands as a significant figure in the history of British art, particularly noted for his contribution to the revival of still life painting during the 19th century. Born in 1802 and passing away in 1864, Lance dedicated much of his artistic career to the meticulous and vibrant depiction of fruits, flowers, and other inanimate objects, achieving considerable recognition in his lifetime for his technical skill and aesthetic sensibility. Though he also explored historical subjects and portraiture, it was his mastery of still life that secured his reputation.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

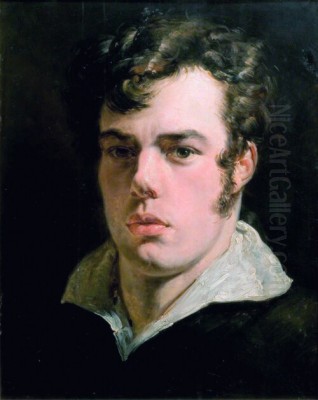

George Lance was born into the world on March 24, 1802, at the old manor house in Little Easton, near Great Dunmow in Essex. His family background provided a somewhat diverse heritage; his father, William Lance, had served in a regiment of light horse cavalry before becoming an adjutant in the Essex yeomanry and later holding the position of inspector of the horse patrol for Bow Street. His mother, Lucia Constable Lance (née Madden), was the daughter of a Colonel Madden from Beverley in Yorkshire, adding a connection to the northern gentry.

From an early age, George displayed a natural aptitude for drawing. This nascent talent suggested a future path distinct from the more conventional careers of the time. Recognizing his potential, his family supported his artistic ambitions. At the young age of 14, around 1816, Lance made the pivotal move from the Essex countryside to the bustling artistic hub of London. This relocation was crucial, placing him in the environment necessary to receive formal training and immerse himself in the city's vibrant art scene.

Training Under Benjamin Robert Haydon

Upon arriving in London, Lance sought out instruction from a prominent, albeit controversial, figure in the art world: Benjamin Robert Haydon. Haydon was primarily known as a history painter, championing the grand manner and large-scale historical and mythological canvases, a genre considered the pinnacle of artistic achievement at the time, following the academic hierarchy promoted by figures like Sir Joshua Reynolds decades earlier. Lance entered Haydon's studio as a pupil, embarking on a rigorous period of study.

Haydon's influence on Lance was initially geared towards history painting. He encouraged his student to pursue this elevated genre, providing instruction in drawing, composition, and anatomy – essential skills for depicting complex human figures and narratives. Lance spent approximately seven years under Haydon's tutelage, absorbing the principles of academic art. During this time, he would have been exposed to Haydon's passionate, often polemical, views on art and his struggles against the establishment, including the Royal Academy.

However, Haydon's career was notoriously tumultuous, marked by financial instability and clashes with patrons and institutions. In 1823, Haydon's mounting debts led to his imprisonment, an event that effectively ended Lance's formal apprenticeship under him. This period was undoubtedly formative, providing Lance with a strong technical foundation, even if he ultimately diverged from Haydon's preferred genre. Other artists associated with Haydon's circle included Charles Eastlake and Edwin Landseer, who also achieved significant fame, though primarily in different fields.

Royal Academy Studies and Early Development

Alongside his studies with Haydon, George Lance also sought instruction at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. Admission to the RA Schools was a significant step for any aspiring artist, offering access to life drawing classes, lectures, and the opportunity to study classical sculpture. Lance is known to have diligently studied anatomy, a discipline considered crucial not only for history painters like his master Haydon but also for any artist aiming for accurate representation of form, whether human or animal, reminiscent of the dedication shown by earlier artists like George Stubbs.

A notable aspect of his studies involved drawing from the Elgin Marbles, the collection of classical Greek sculptures controversially brought to Britain by Lord Elgin and housed in the British Museum. Haydon himself was a fervent admirer and defender of the Marbles, believing them to represent the zenith of artistic perfection. Lance produced large, detailed drawings from these sculptures, honing his draughtsmanship and understanding of classical form. This rigorous academic grounding provided him with versatile skills applicable across different genres.

Despite Haydon's strong advocacy for history painting, Lance began to find his true calling in a different area. A perhaps apocryphal, yet telling, anecdote suggests his shift towards still life occurred somewhat serendipitously. While still in Haydon's studio, he painted a study of fruit simply to keep his hand busy while waiting for his master. A visitor to the studio saw the study and promptly purchased it. This initial success, coupled with a growing personal inclination, seems to have steered Lance towards specializing in still life.

The Turn to Still Life and Early Success

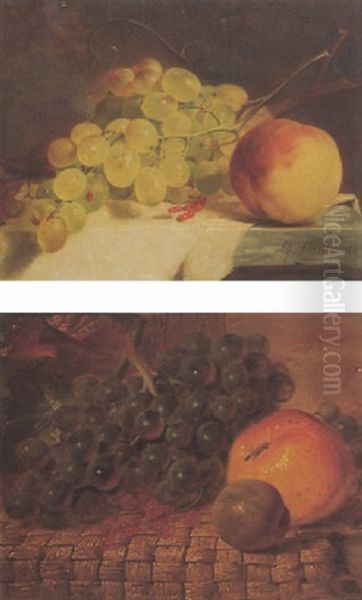

Around the age of 23, Lance made a conscious decision to focus his artistic energies primarily on still life painting. This was a significant choice, as still life occupied a lower rung on the traditional hierarchy of genres compared to history painting. However, Lance recognized his particular talent for capturing the textures, colours, and forms of inanimate objects, particularly fruit and flowers, with remarkable fidelity and vibrancy.

His burgeoning reputation in this field was cemented by an encounter with the influential collector and connoisseur Sir George Beaumont. Beaumont, a key figure in the founding of the National Gallery and a patron of artists like John Constable and Sir David Wilkie, saw one of Lance's fruit pieces, possibly the work titled Fruit Boy, and was greatly impressed. He purchased the painting and, importantly, encouraged Lance to continue pursuing this genre, effectively giving his specialization a significant endorsement.

This early patronage was crucial. Further commissions followed, including work for the Duke of Bedford. Lance painted a series of fruit panels designed to decorate the dining room at Woburn Abbey, the Duke's ancestral home. These commissions from prominent aristocratic patrons helped establish Lance's reputation and demonstrated a growing market for high-quality still life painting among the British elite. His success signaled a potential shift in taste and a renewed appreciation for the genre.

Artistic Style and Influences

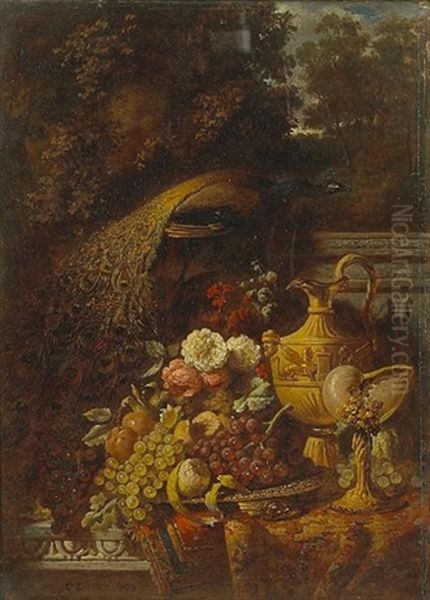

George Lance's style is characterized by its meticulous detail, rich colouring, and realistic rendering of textures. He excelled at depicting the bloom on grapes, the fuzz on peaches, the gleam of polished metal, and the intricate patterns of flowers or bird plumage. His compositions are often abundant and complex, featuring arrangements of fruit, game, flowers, and decorative objects like goblets, urns, or antique vessels.

His approach was deeply influenced by the great masters of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish still life painting. He particularly admired the work of artists like Jan van Huysum, known for his elaborate and highly finished flower pieces, and likely drew inspiration from the opulent compositions of painters such as Jan Davidsz. de Heem or the detailed realism of Willem Kalf. Unlike some earlier still life traditions that emphasized vanitas themes (moral allegories about the transience of life), Lance's work, reflecting the spirit of the 19th century, often focused more on the direct observation and celebration of natural beauty and abundance.

This focus on empirical observation aligned with the broader scientific and natural history interests prevalent during the Victorian era. Lance's paintings offered viewers a chance to marvel at the diversity and richness of the natural world, rendered with almost scientific precision yet imbued with artistic flair. His ability to create convincing illusions of reality, sometimes bordering on trompe-l'oeil, was a key element of his appeal.

Major Works and Themes

While a comprehensive list of all his works is extensive, certain paintings stand out as representative of his oeuvre. The Golden Peacock, mentioned in the provided texts, exemplifies his skill in creating lavish compositions. Though the exact appearance might vary between versions or similarly titled works, one can imagine a piece featuring the iridescent plumage of a peacock alongside a rich assortment of fruit, flowers, and perhaps ornate objects, showcasing his mastery of diverse textures and brilliant colour.

His fruit pieces were particularly renowned. Works often titled simply Still Life with Fruit, Fruit Piece, or similar variations, formed the core of his output. These typically depicted overflowing baskets or arrangements of grapes, melons, pineapples (a luxury item signifying wealth), peaches, and plums, often combined with wine glasses, earthenware jugs, or silver platters. He captured not just the appearance but also the implied weight and ripeness of the fruit.

Lance did not entirely abandon other genres. He occasionally painted historical scenes, such as Melancthon's First Misgivings of the Church of Rome, which won a prize from the Liverpool Academy. He also produced portraits and genre scenes. However, these were less frequent and less central to his reputation than his still lifes. His exhibition record clearly shows a predominance of fruit and flower subjects throughout his career.

Exhibition Career and Professional Recognition

George Lance was a regular and prolific exhibitor at London's major art institutions, ensuring his work remained visible to the public and potential patrons. His relationship with the Royal Academy of Arts was long-standing; he exhibited there consistently from 1824 until the year of his death in 1864. Over these four decades, he showed a total of 38 paintings at the RA's prestigious annual exhibitions. While not elected a full Academician, his continuous presence indicated the respect his work commanded within the establishment, alongside contemporaries like J.M.W. Turner, William Etty, and his former fellow student Edwin Landseer.

He also frequently submitted works to the British Institution, another important venue for artists in London, known for its exhibitions of both contemporary British art and Old Masters. Lance showed numerous works here, primarily still lifes, further solidifying his position as the leading specialist in the genre. His participation began early in his career and continued for many years.

Furthermore, Lance was associated with the Society of British Artists (SBA), located on Suffolk Street. He began exhibiting with the SBA in 1836. He was also listed as a member of the New Society of Painters in Water Colours (later the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours), indicating his activity and recognition extended beyond oil painting, although his primary fame rests on his works in oil. This consistent exhibition activity across multiple venues ensured his name and distinctive style were well-known in the British art world.

Patronage, Reputation, and International Reach

Lance's meticulous and visually appealing style found favour with wealthy patrons, particularly among the aristocracy and the newly affluent middle classes of Victorian Britain. As mentioned, early support from figures like Sir George Beaumont and the Duke of Bedford was instrumental. His works, often large and decorative, were well-suited for the dining rooms and drawing rooms of grand houses. The level of detail and the luxurious subject matter appealed to Victorian tastes for opulence and naturalism.

His reputation extended beyond the circles of high society. His paintings were popular enough to be reproduced as prints, making his imagery accessible to a wider audience. Moreover, his fame was not confined to Britain. His works found their way into collections in the United States, Australia, and Canada during the 19th century, indicating an international appreciation for his particular brand of still life.

Art critics of the time generally acknowledged Lance's exceptional technical skill. While still life might not have garnered the same critical reverence as history painting, Lance was recognized as the preeminent practitioner of the genre in Britain during his era. He effectively revived and elevated a category of painting that had received less attention from major British artists in the preceding decades. His success demonstrated that specialization in still life could lead to a prosperous and respected career.

Context within 19th-Century British Art

George Lance occupies a unique position in 19th-century British art. He emerged during a period when Romanticism was still influential, and the grand historical narratives championed by his teacher Haydon were considered the highest form of art. However, Lance carved out his niche by excelling in a genre often relegated to a secondary status. His dedication to still life can be seen as part of a broader Victorian interest in detailed observation and the natural world.

While not directly associated with major movements like the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (founded in 1848), Lance's commitment to detailed realism shares some superficial similarities with their "truth to nature" ethos, although his style remained rooted in older traditions, particularly Dutch Baroque realism, rather than the sharp focus and bright palette of artists like William Holman Hunt or John Everett Millais.

His career demonstrated the viability and appeal of specialized genre painting in the expanding Victorian art market. He essentially became the leading figure in British still life for several decades, filling a void and setting a standard for technical excellence in the depiction of inanimate objects. His success may have encouraged other artists to explore the genre more seriously.

Later Life, Death, and Legacy

George Lance continued to paint and exhibit actively throughout his middle age. He maintained his studio in London for many years but eventually sought a change of scenery. In his later years, seeking respite perhaps due to declining health, he moved to Birkenhead, near Liverpool, to live with his son. It was there, across the Mersey River from the bustling port city, that his health ultimately failed him.

George Lance passed away on June 18, 1864, at the age of 62. He died in Sunnyside, near Birkenhead, Cheshire. His death marked the end of a long and productive career dedicated almost entirely to the art of still life.

For a period after his death, like many Victorian artists, Lance's reputation somewhat faded as artistic tastes shifted towards modernism. However, his work was never entirely forgotten, particularly by collectors of traditional British art. In the later 20th and early 21st centuries, there has been a renewed appreciation for Victorian painting, and Lance's contributions have been re-evaluated. His works continue to appear at auction, sometimes commanding significant prices, as evidenced by mentions of sales at Christie's. His paintings are held in numerous public collections in the UK and abroad, including the Tate Britain and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

His legacy lies in his role as a pivotal figure in the resurgence of still life painting in Britain. He brought a high level of technical proficiency and aesthetic appeal to the genre, influencing subsequent generations of artists who specialized in similar subjects. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries in other fields, George Lance remains a master of his chosen craft, whose detailed and vibrant depictions of nature's bounty continue to delight viewers today. His dedication proved that mastery within a specific genre could achieve lasting recognition, even against the prevailing artistic hierarchies of his time. Later British artists interested in still life, such as William Nicholson, though working in a very different, more modern style, operated in a field where Lance had already established a high benchmark for quality and professional success.

Conclusion

George Lance was more than just a painter of fruit; he was a dedicated artist who, through immense skill and focus, revitalized the genre of still life painting in 19th-century Britain. Emerging from the shadow of his history-painting master, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Lance found his true calling in the meticulous and celebratory depiction of the natural world's textures and colours. Influenced by Dutch masters like Jan van Huysum but developing his own distinctively rich and detailed style, he gained significant patronage from collectors such as Sir George Beaumont and the Duke of Bedford. His consistent presence at major exhibitions like the Royal Academy and the British Institution cemented his reputation as the foremost still life specialist of his day. Though his fame waned temporarily after his death in 1864, George Lance's work is now recognized for its technical brilliance and its important role in the history of British art, securing his place as a master observer and painter of nature's quiet beauty.