George Leslie Hunter stands as a pivotal figure in early 20th-century Scottish art. Born in Rothesay on the Isle of Bute on August 7, 1877, he would become one of the celebrated quartet known as the Scottish Colourists. Though his life was tragically cut short in 1931, Hunter's vibrant canvases, marked by an intuitive grasp of light and an audacious use of colour, left an indelible mark on the trajectory of modern art in Britain. His journey was unconventional, largely self-directed, and profoundly shaped by experiences on both sides of the Atlantic and in continental Europe.

Early Life and Transatlantic Beginnings

Hunter's initial years were spent in Scotland, but his formative artistic development began after his family emigrated to California when he was a teenager. Unlike many of his contemporaries who followed structured academic paths, Hunter was largely self-taught in his early years. He possessed a natural aptitude for drawing, which initially led him towards illustration work for magazines and newspapers in San Francisco around the turn of the century. This period provided practical experience in composition and line, honing observational skills that would underpin his later painting.

During his time in California, Hunter moved within circles that included writers and artists. He formed friendships with figures such as the writer Irwin Will and even provided illustrations for a book by the famous author of Western stories, Bret Harte. This connection to the literary world hints at a broad cultural engagement beyond the purely visual arts. However, his primary ambition lay in painting, and he began to explore this medium more seriously, absorbing the atmosphere and light of the American West Coast.

A significant and devastating event marked this early phase. Hunter had gathered enough work to mount his first solo exhibition, planned for the Mark Hopkins Institute of Art in San Francisco in 1906. Tragically, the catastrophic San Francisco earthquake and subsequent fire struck just before the exhibition opened, destroying the gallery and, devastatingly, Hunter's entire collection of early works. This disaster was a profound setback, wiping out years of effort and forcing a major re-evaluation of his path.

Parisian Exposure and Artistic Awakening

Likely spurred by the destruction in San Francisco and a desire to immerse himself in the European art scene, Hunter travelled to Paris around 1904, possibly visiting before the earthquake as well. This period was transformative. Paris was the undisputed centre of the art world, buzzing with revolutionary ideas. Hunter encountered firsthand the works of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, artists who were fundamentally changing the language of painting.

The impact of French modernism on Hunter was immediate and profound. He absorbed the lessons of artists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir in capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. More significantly, he was drawn to the structural innovations and colour theories of Post-Impressionists such as Paul Cézanne, whose methodical application of colour to build form resonated deeply. The expressive intensity and bold palette of Vincent van Gogh also left a clear mark, visible in Hunter's later energetic brushwork and heightened colour.

Perhaps the most crucial influence from this period was Henri Matisse and the Fauves ('wild beasts'), whose radical use of non-naturalistic, vibrant colour for emotional and decorative effect was causing a sensation around the time of Hunter's visits. Hunter's own developing style would embrace this liberation of colour, using it not just descriptively but as a primary means of expression. This exposure provided him with the artistic vocabulary he needed to move beyond illustration and fully embrace painting.

Return to Scotland and the Glasgow Scene

Following the San Francisco disaster and his European studies, Hunter returned to Scotland, eventually settling in Glasgow around 1906. Glasgow was a dynamic city with a burgeoning art scene, distinct from the more established traditions of Edinburgh. He connected with influential dealers, most notably Alexander Reid, whose gallery, La Société des Beaux-Arts, was instrumental in promoting both contemporary Scottish artists and the French avant-garde, including the Impressionists.

Hunter held his first solo exhibition in Scotland at Reid's gallery. This marked his arrival on the Scottish art scene as a painter of note. He began to focus intently on his craft, primarily exploring still life and landscape subjects. His work started to attract attention for its freshness, its vibrant palette, and its departure from the more staid academic styles prevalent at the time. He was finding his voice, synthesizing his Californian experiences and Parisian influences within a Scottish context.

The environment in Glasgow, with its network of artists, dealers like Reid and later Aitken Dott in Edinburgh, and collectors receptive to modern trends, provided fertile ground for Hunter's development. He began to associate with other painters who shared a similar outlook, absorbing the lessons of French modernism and applying them to Scottish subjects with a distinctive flair.

The Scottish Colourists: A Shared Sensibility

Hunter is inextricably linked with three other painters: Samuel John Peploe, John Duncan Fergusson, and Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell. Together, they became known posthumously as the Scottish Colourists. It's important to note that they were not a formal group or movement with a manifesto; rather, they were contemporaries and friends who shared an affinity for the developments in French painting, particularly the work of the Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, and Fauves.

Each artist had his own distinct personality and stylistic trajectory. Peploe, perhaps the most intellectually rigorous, shared Hunter's admiration for Cézanne and Édouard Manet, focusing intensely on still life composition. Fergusson, who spent much of his career in France, embraced dynamic figure compositions and scenes of modern life, heavily influenced by Fauvism. Cadell, known for his elegant interiors and portraits, often worked with a brighter, higher key palette, particularly in his depictions of Iona.

While they occasionally exhibited together and certainly knew and respected each other's work, there's little evidence of direct collaboration in the sense of co-authored works. Their connection lay in a shared commitment to colour as the primary vehicle of expression and a mutual admiration for French modernism, which set them apart from the mainstream of British art. Hunter, with his less formal training and perhaps more intuitive approach, brought a unique energy to this constellation. His background in California and his specific responses to artists like Matisse and Van Gogh coloured his contribution distinctly. Their collective impact was to introduce a bold, continental modernism into Scottish painting.

Artistic Style: Mastery of Still Life

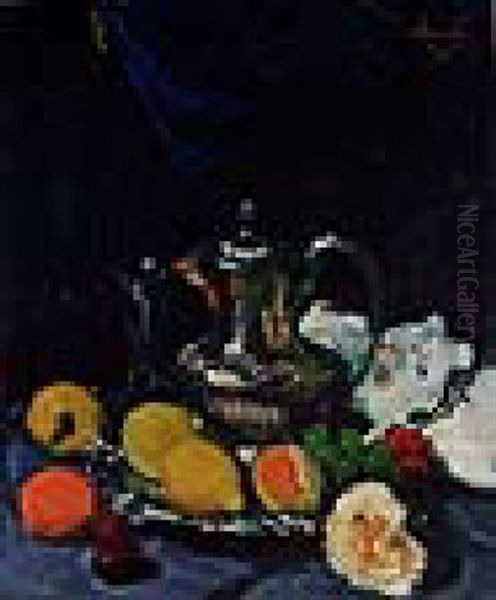

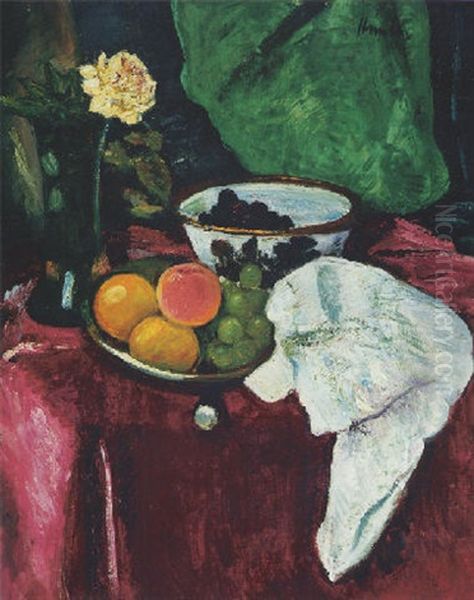

Still life became a central preoccupation for George Leslie Hunter throughout his career, and it is in this genre that his stylistic evolution is perhaps most clearly traced. Influenced by the French tradition, from the quiet intensity of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin to the revolutionary compositions of Cézanne and the vibrant arrangements of Matisse, Hunter made the genre his own.

His earlier still lifes, while demonstrating a strong sense of colour, sometimes retained a tighter structure and more detailed rendering, possibly reflecting his background as an illustrator. However, as he matured, his approach became increasingly bold and free. He developed a remarkable ability to orchestrate complex arrangements of fruit, flowers, ceramics, and fabrics into dynamic compositions, energized by colour harmonies and contrasts.

Works like Apples in a White Fruitbowl showcase his developing confidence. Here, the fruit and bowl are rendered with substantial, tactile brushstrokes, and the interplay of light and shadow across the surfaces is keenly observed. Colour is rich and resonant, moving beyond simple description. By the 1920s, his style reached full maturity. Still Life with Gladioli (c. 1927-30) exemplifies this later phase: the brushwork is loose and energetic, applying thick impasto in places. The composition feels spontaneous yet perfectly balanced, with vibrant reds, pinks, and greens singing against the background elements, like the patterned cloth and books, which are themselves treated with painterly freedom. Similarly, Apples and Pink Roses (1925) demonstrates his sophisticated handling of light, colour layering, and texture to create an image that is both visually arresting and emotionally resonant. He wasn't just depicting objects; he was exploring the pure joy of seeing and painting, translating the sensuous qualities of the world into pigment.

Artistic Style: Landscapes and the Scottish Light

While renowned for his still lifes, Hunter was also a gifted landscape painter. He travelled within Scotland, particularly drawn to the landscapes of Fife on the east coast and the dramatic scenery around Loch Lomond in the west. His landscape works demonstrate the same commitment to colour and light that characterized his still lifes, but adapted to capture the specific atmosphere and changing conditions of the outdoors.

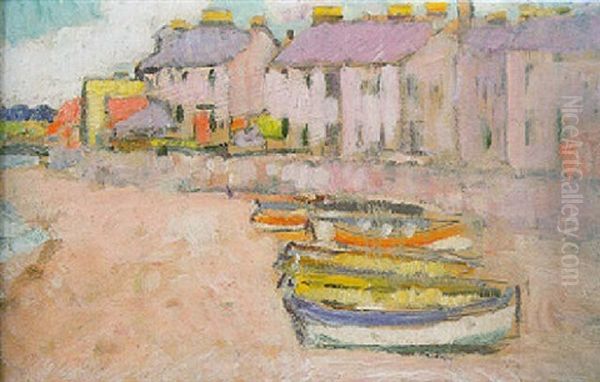

His Fife landscapes, such as Fishing Boats, Largo, capture the bright, clear light often found on the coast. He depicted harbours, beaches, and cottages with vigorous brushwork and a palette that could be both luminous and strong. He was adept at simplifying forms to their essential shapes and colours, conveying the feeling of the place rather than a meticulous topographical record. This approach aligns him with the Impressionist practice of plein air painting, seeking to capture the immediate sensory experience.

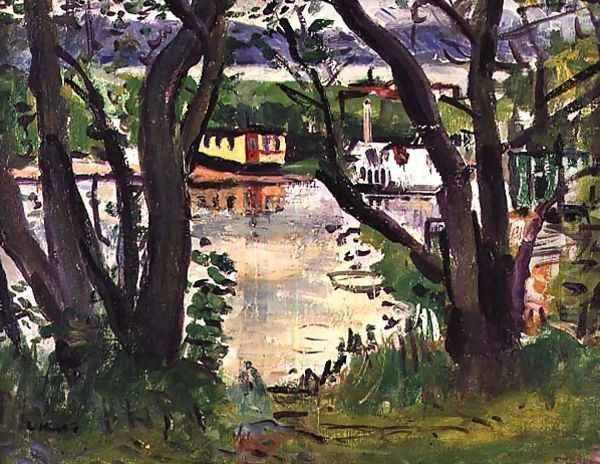

In works depicting Loch Lomond, the mood might shift, reflecting the softer light and more expansive vistas of the western Highlands. Loch Lomond paintings often feature broad sweeps of colour for water and sky, with the forms of hills and trees rendered with expressive strokes. Hunter managed to convey the unique quality of Scottish light – sometimes brilliant and sharp, other times soft and diffused – through his masterful handling of colour temperature and tonal relationships. His ability to capture these fleeting effects owes something to the legacy of British landscape masters like J.M.W. Turner, as well as the French Impressionists. He also travelled abroad, painting vibrant scenes in the South of France, following in the footsteps of Van Gogh and Cézanne, finding inspiration in the intense Mediterranean light and colour.

Travels, Later Development, and Recognition

Hunter continued to travel throughout his career, seeking fresh inspiration. Journeys to the South of France in the 1920s proved particularly fruitful. The intense sunlight and vibrant colours of Provence further liberated his palette, resulting in some of his most radiant landscapes and still lifes. He also visited Italy, absorbing the lessons of the Italian masters and the beauty of the landscape. These travels constantly refreshed his vision and provided new motifs.

Despite his growing reputation among critics and collectors, Hunter, like the other Colourists, remained somewhat outside the official art establishment in Britain. He never achieved the academic honours bestowed on more conservative painters. However, his work was increasingly sought after, and he exhibited regularly in Glasgow, Edinburgh, London, and even Paris.

A significant moment of recognition came when one of his paintings was acquired by the French state for the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris. This was a considerable honour for a foreign artist. Hunter himself reportedly remarked with characteristic modesty and perhaps a touch of weary satisfaction, "I have been knocking at the door, and at last it is beginning to open." This anecdote highlights the long struggle for recognition faced by artists pursuing a modern path. His works also began to perform well commercially, achieving solid prices at auction, indicating a growing appreciation in the market.

Challenges and Premature End

Hunter's life and career were marked by recurring challenges. The early setback of the San Francisco earthquake was a significant blow. Furthermore, throughout his adult life, he reportedly struggled with periods of ill health, both physical and possibly psychological. These struggles may have contributed to the intensity and urgency found in his work, but they also undoubtedly took a toll.

His career, which had gained significant momentum by the late 1920s, was tragically cut short. George Leslie Hunter died in Glasgow on December 7, 1931, at the relatively young age of 54. His death came at a point when his artistic powers were arguably at their height, leaving a sense of unfulfilled potential alongside his already substantial achievements. His life story carries a poignant quality – a "sweet and bitter" narrative, as one source described it, marked by brilliant artistic breakthroughs achieved against a backdrop of personal adversity and culminating in a premature end.

Legacy and Influence

Despite his relatively short career and lack of official accolades during his lifetime, George Leslie Hunter's influence on Scottish art has been profound and enduring. As one of the four Scottish Colourists, he played a crucial role in introducing and adapting the language of French modernism for a Scottish audience. The Colourists collectively brought a new vibrancy, freedom, and emphasis on the expressive power of colour to British painting.

Hunter's specific contribution lies in his intuitive, often sensuous response to colour and light, his energetic brushwork, and his ability to infuse both still lifes and landscapes with vitality. His work demonstrated that modern artistic principles could be applied to traditional subjects with stunning results. He helped pave the way for subsequent generations of Scottish artists who continued to explore colour and expressive painting, including figures like Joan Eardley and Anne Redpath, who, while developing their own unique styles, shared a similar commitment to painterly values.

Today, Hunter's paintings are highly prized by collectors and institutions. His works are held in major public collections across the UK and beyond. Retrospectives of his work and exhibitions dedicated to the Scottish Colourists continue to attract large audiences, testament to the enduring appeal of his vibrant and life-affirming art. He remains celebrated as a master of colour, a key figure in the story of Scottish modernism, and an artist whose unique vision continues to resonate.

Conclusion: A Luminous Vision

George Leslie Hunter's artistic journey was one of resilience, self-discovery, and a passionate engagement with the visual world. From his early days in California, through the transformative encounter with French modernism in Paris, to his mature years painting the landscapes and still lifes of Scotland and Europe, he forged a distinctive and influential style. His bold use of colour, his sensitivity to light, and his expressive brushwork mark him as a standout talent within the Scottish Colourist group and a significant figure in British Post-Impressionism. Though his life was marked by challenges and ended too soon, the luminous canvases he left behind continue to captivate viewers, securing his legacy as a painter who truly understood the power and joy of colour.