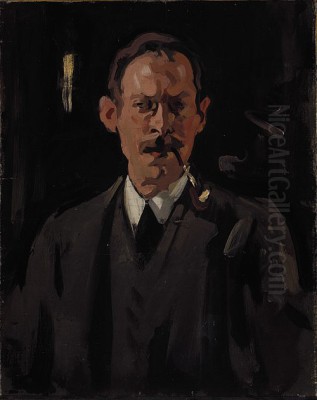

Samuel John Peploe stands as a pivotal figure in early 20th-century Scottish art. Born in Edinburgh on January 27, 1871, and passing away in the same city on October 11, 1935, Peploe carved a distinct path as a Post-Impressionist painter. He is celebrated primarily for his vibrant still life compositions and his masterful command of colour, qualities that cemented his position as one of the four core members of the influential group known as the Scottish Colourists. Alongside his close associates John Duncan Fergusson, Francis Cadell, and Leslie Hunter, Peploe brought a uniquely Scottish sensibility to the revolutionary developments occurring in French painting, creating a legacy that continues to resonate.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born at 39 Manor Place, Edinburgh, Samuel John Peploe hailed from a background of relative stability; his father, Robert Luff Peploe, was a bank manager, specifically the Commercial Secretary for the Commercial Bank of Scotland. His mother was Anne Watson. Despite familial expectations pointing towards a respectable career in law, the young Peploe felt an undeniable pull towards the arts. He decisively turned away from legal studies to pursue his true passion.

His formal artistic training began in Edinburgh at the Trustees' Academy and later at the Royal Scottish Academy schools around 1893-94. Seeking broader horizons and exposure to continental trends, Peploe, like many aspiring artists of his generation, travelled to Paris in 1894. There, he immersed himself in the vibrant artistic milieu, studying at the renowned Académie Julian and the Académie Colarossi. These institutions were melting pots of international talent and progressive ideas, providing Peploe with invaluable technical grounding and exposure to diverse artistic currents.

During this formative period in Paris, Peploe absorbed the lessons of French art, both past and present. He was particularly drawn to the elegance and tonal subtlety of James McNeill Whistler, an American expatriate whose aesthetic theories were highly influential. The realism and modern subject matter of Édouard Manet also made a significant impression, encouraging Peploe to look at the world with fresh eyes. Furthermore, the work of Edgar Degas, with its innovative compositions and focus on contemporary life, likely contributed to Peploe's developing artistic vision. A trip to the Netherlands in 1895 further enriched his understanding, allowing him to study the rich tradition of Dutch still life painting firsthand, admiring the technical brilliance of masters like Rembrandt van Rijn and Frans Hals, alongside the Spanish master Diego Velázquez and the French still-life virtuoso Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin.

The Emergence of a Colourist

Returning to Scotland, Peploe began to establish his artistic identity. In 1901, he married Margaret Mackay and settled in Edinburgh, setting up a studio that would become the crucible for his early mature work. His initial style, heavily influenced by his studies of 17th-century Dutch painting and the tonalism of Whistler, was characterized by a relatively dark palette, rich, textured surfaces achieved through thick application of paint (impasto), and a focus on capturing the interplay of light and shadow on objects. His subjects were often traditional still lifes – arrangements of bottles, crockery, fruit, and flowers – rendered with a palpable sense of substance and presence.

Friendship and artistic dialogue played a crucial role in Peploe's development. He formed a close bond with John Duncan Fergusson (J.D. Fergusson), another aspiring Edinburgh artist who shared his enthusiasm for modern French painting. In 1901, the two friends embarked on a painting trip to Northern France. This experience exposed them to the principles of painting en plein air (outdoors) and the brighter palettes associated with Impressionism, although Peploe's work from this period still retained a certain weightiness. The influence of Rural Realism, perhaps encountered through the works of artists like Jules Bastien-Lepage, also filtered into his approach during these travels.

Throughout the first decade of the 20th century, Peploe steadily refined his craft, exhibiting his work and gaining recognition within the Scottish art scene. While his early works demonstrated technical skill and a deep appreciation for painterly traditions, his engagement with French Impressionism gradually began to lighten his palette and loosen his brushwork, hinting at the dramatic transformation that lay ahead. He absorbed the lessons of Impressionists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir regarding the capture of fleeting light and atmospheric effects, though his inherent interest in structure and form remained strong.

Parisian Transformation

The year 1910 marked a watershed moment in Peploe's artistic journey. He and his family, along with J.D. Fergusson, moved to Paris. This relocation plunged Peploe directly into the epicentre of the European avant-garde. Paris was buzzing with radical new art forms, most notably Fauvism and the nascent stirrings of Cubism. Peploe was immediately captivated by the explosive, non-naturalistic colour employed by the Fauves ('wild beasts'), including Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice de Vlaminck. Their liberation of colour from purely descriptive purposes resonated deeply with his own burgeoning chromatic sensibilities.

Exposure to these revolutionary movements fundamentally altered Peploe's approach. His palette underwent a dramatic brightening, embracing pure, vibrant hues applied with a newfound boldness. He began experimenting with flatter planes of colour, stronger outlines (often using distinctive deep blues), and a more deliberate emphasis on compositional structure and design. The influence of Post-Impressionist masters became paramount during this period. Paul Cézanne's rigorous analysis of form and structure provided a crucial model for Peploe's increasingly architectonic compositions.

Furthermore, Peploe encountered the work of Vincent van Gogh, likely seeing his paintings at exhibitions in Paris. Van Gogh's intense emotional expression, conveyed through dynamic brushwork and heightened colour – particularly his use of vibrant yellows and expressive rendering of natural forms like twisted stems – left a distinct mark on Peploe's work from this period. This Parisian sojourn, lasting until 1912 or 1913, was a period of intense experimentation and growth, resulting in some of his most daring and chromatically brilliant paintings. He shed the darker tones and heavy impasto of his earlier years, adopting techniques like dry brush application which allowed for cleaner colour and crisper forms.

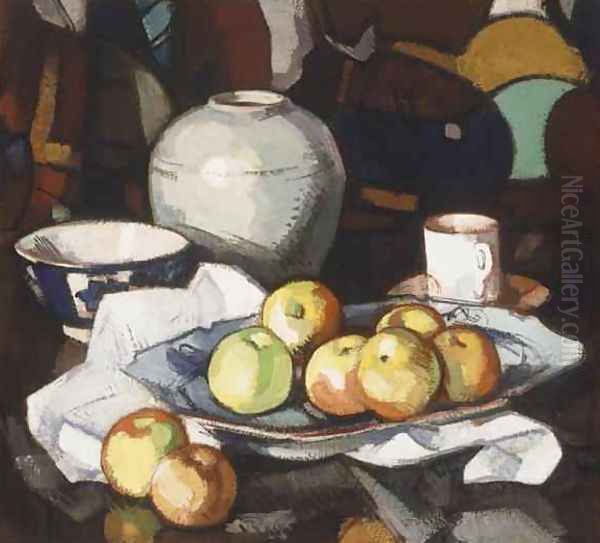

Mastery of Still Life

While Peploe also painted landscapes and occasionally figures, still life remained the central pillar of his artistic practice throughout his career. It was in this genre that his stylistic evolution is most clearly charted and his unique contribution most profoundly felt. His early still lifes, influenced by Dutch masters and Chardin, demonstrated a concern for realism, texture, and chiaroscuro. He excelled at rendering the varied surfaces of objects – the gleam of pottery, the softness of petals, the solidity of fruit – within carefully arranged compositions.

Following his transformative Paris years, Peploe's approach to still life became bolder and more modern. He retained his meticulous attention to composition but now infused it with the vibrant colour lessons learned from the Fauves and the structural concerns derived from Cézanne. His arrangements often featured recurring motifs: elegant ceramic vases, bowls of fruit, and, most famously, flowers – particularly tulips and roses – set against patterned drapery or plain backgrounds. Works like Tulips, Roses and Fruit (considered by some a pinnacle achievement), and The Black Bottle exemplify this mature phase.

Peploe treated still life not merely as an exercise in representation but as a formal laboratory for exploring colour relationships, spatial dynamics, and the interplay of shapes and lines. He carefully orchestrated the elements within the picture plane, balancing areas of intense colour with calmer passages, and using strong outlines to define forms while simultaneously integrating them into the overall design. His later still lifes, from the 1920s onwards, sometimes show a return to a slightly more modulated palette and a greater emphasis on subtle tonal variations, yet they retain the underlying structural integrity and sophisticated colour sense that define his best work. He achieved a remarkable synthesis of sensuous colour and intellectual rigour.

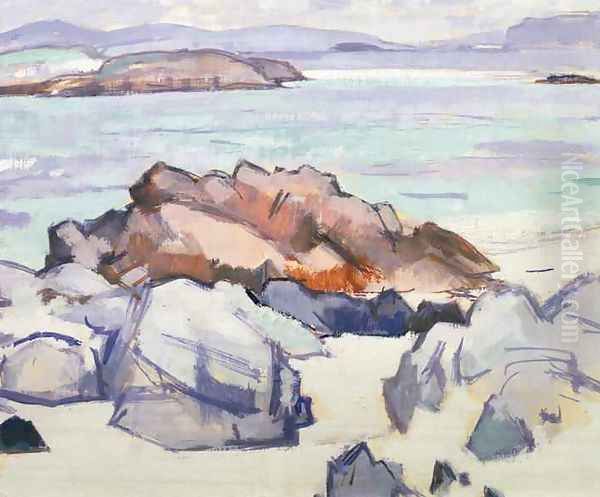

Landscapes of Scotland and France

Alongside his dedication to still life, Peploe was a sensitive and accomplished landscape painter. His travels provided ample inspiration, from the coasts of Northern France to the dramatic scenery of the Scottish Highlands and Islands. Early landscapes, like his early still lifes, often employed a darker palette and reflected an interest in tonal harmonies, perhaps echoing the work of earlier Scottish landscape painters like William McTaggart, known for his atmospheric depictions of sea and sky.

His time in France yielded bright, sun-drenched canvases capturing the light and atmosphere of coastal resorts, such as the work titled Paris-Plage. These paintings clearly show the impact of Impressionism and Fauvism, with their broken brushwork and heightened colour schemes designed to convey the immediacy of the visual experience.

However, it was the landscape of Scotland, particularly the Hebridean islands of Iona and Barra, that became a recurring source of inspiration, especially from the 1920s onwards. Peploe often visited these islands, sometimes in the company of his fellow Colourist Francis Cadell. The unique quality of light, the rugged rock formations, and the intense blues and greens of the sea and landscape captivated him. In works like Rocks, Iona and Rocks, Barra, he translated the wild beauty of these locations into powerful compositions characterized by simplified forms, bold colour contrasts, and a strong sense of design, applying the principles honed in his still life practice to the natural world. He captured the essence of the place rather than merely its topographical detail, using colour and form to evoke its spirit and atmosphere.

The Scottish Colourists

Samuel John Peploe is inextricably linked with the Scottish Colourists, the group that also included J.D. Fergusson, Francis Cadell, and Leslie Hunter. While never a formally constituted society with a manifesto, these four artists shared a common trajectory: they emerged from a Scottish artistic background, were profoundly influenced by modern French painting (particularly Post-Impressionism and Fauvism), and developed distinctive styles characterized by bold colour and expressive handling of paint. They represented a significant break from the more conservative traditions prevalent in Scottish art at the time, aligning themselves with the European avant-garde.

Peploe and Fergusson had the earliest and perhaps closest artistic relationship, sharing formative experiences in France. Cadell, known for his elegant interiors and Iona landscapes, shared Peploe's fascination with the Hebridean light. Leslie Hunter, whose path was somewhat different (including time spent in California, where he associated with figures like Bret Harte and Jack London and worked as an illustrator for publications like Overland Monthly before returning to focus on painting), brought a lyrical and often richly textured approach to still life and landscape.

Each Colourist maintained a distinct artistic personality. Peploe was arguably the most analytical and focused on formal structure, particularly in his still lifes. Fergusson's work often explored dynamic figure compositions and a broader range of modern life subjects. Cadell possessed a fluid, elegant style, while Hunter's work was often characterized by its vibrant energy and intuitive feel for colour. Together, however, they formed a powerful force, championing modernism north of the border and challenging the established tastes promoted by institutions like the Royal Scottish Academy (though Peploe himself was elected an Academician later in life). Their work can be seen in dialogue not only with French moderns but also with earlier Scottish movements like the Glasgow Boys (e.g., James Guthrie, E.A. Walton), who had also looked to French naturalism and plein-air painting a generation earlier.

Later Years and Mature Style

After the interruption of the First World War, during which Peploe returned to Edinburgh, he entered a period of consolidation and refinement. While the initial shock of Fauvist colour perhaps subsided slightly, his commitment to chromatic richness and structural composition remained unwavering. He continued to paint his signature still lifes, often featuring tulips and roses, exploring subtle variations in arrangement, light, and colour harmony. His technique became increasingly assured and sophisticated.

The 1920s saw him make frequent painting trips to the Hebrides, particularly Iona, often with Cadell. These trips yielded a significant body of landscape work that captured the unique light and atmosphere of the islands. Some art historians note a shift towards a slightly more naturalistic representation and a cooler palette in some works from the later 1920s, though still underpinned by a strong sense of design. He continued to exhibit regularly in Edinburgh, Glasgow, and London, solidifying his reputation as one of Scotland's leading modern painters.

His dedication to his craft was absolute. He was known for his meticulous approach, constantly experimenting with the arrangement of objects in his still lifes until achieving the perfect balance of colour, form, and space. This rigorous process, combined with his innate sensitivity to colour, resulted in works that possess both intellectual depth and sensuous appeal. He held his first solo exhibition in the 1910s and continued to be a prominent figure in the Scottish art world until his death.

Legacy and Influence

Samuel John Peploe died in Edinburgh in 1935. He left behind a significant body of work that secured his place as a major figure in British art of the early 20th century. His primary legacy lies in his role as a key member of the Scottish Colourists, a group whose vibrant and modern approach revitalized Scottish painting. Peploe's particular contribution was his intense, analytical exploration of still life, transforming it into a vehicle for profound investigations of colour and form, heavily influenced by French modernism yet retaining a unique sensibility.

His work demonstrated how Scottish artists could engage with the most advanced European art movements while forging a distinct national identity. He successfully synthesized the painterly traditions he admired (from Dutch Masters to Manet) with the radical innovations of Cézanne, Van Gogh, and the Fauves. His influence extended to subsequent generations of Scottish artists who admired his sophisticated colour sense and strong compositional skills.

Today, Peploe's paintings are highly sought after and reside in major public collections across the world, including the National Galleries of Scotland, Tate Britain, the Hunterian Art Gallery in Glasgow, Aberdeen Art Gallery, the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, the Princeton University Art Museum in the USA, and the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Australia, among others. His works also frequently appear at auction, commanding high prices that reflect his enduring importance. He is buried in the family plot in the historic Dean Cemetery in Edinburgh.

Conclusion

Samuel John Peploe was more than just a painter of beautiful objects; he was a relentless explorer of the formal possibilities of painting. Through his dedication primarily to still life, but also through his evocative landscapes, he forged a unique style characterized by vibrant colour, rigorous composition, and exquisite sensitivity to light and texture. As a leading Scottish Colourist, he played a crucial role in bringing the spirit of French modernism to Scotland, translating its revolutionary ideas into a distinctly personal and enduring artistic language. His legacy is one of chromatic brilliance, formal integrity, and a profound contribution to the story of modern Scottish art.