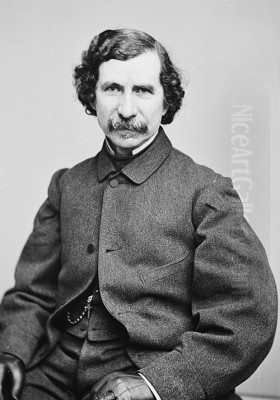

George Peter Alexander Healy stands as one of the most prolific and celebrated American portrait painters of the 19th century. His career, spanning several decades and two continents, saw him capture the likenesses of statesmen, presidents, royalty, and prominent cultural figures, leaving behind an invaluable visual record of his era. Born into humble beginnings, Healy's innate talent and relentless ambition propelled him to the heights of artistic success, making him a sought-after artist in both the United States and Europe. His work, deeply rooted in the academic traditions of his time, combined technical finesse with a keen ability to convey the character of his sitters.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Boston

George Peter Alexander Healy was born on July 15, 1813, in Boston, Massachusetts. He was the eldest child of William Healy, an Irish immigrant and merchant sea captain, and Mary Hicks Healy. The family faced financial hardships, particularly after Captain Healy's voyages became less frequent. Young George displayed an early aptitude for art, a passion that offered both a personal outlet and a potential means of supporting his family.

By the age of sixteen, Healy was already demonstrating a remarkable talent for drawing and painting. Around 1830, at the tender age of seventeen or eighteen, he took the bold step of opening his own portrait studio in Boston. His initial efforts were focused on earning a livelihood and honing his skills. A significant moment in his early career was the encouragement he received from the established portraitist Thomas Sully. Sully, a leading figure in American art known for his elegant and romanticized portraits, recognized Healy's potential and advised him to pursue further study, particularly in Europe. This encouragement likely solidified Healy's resolve to seek formal training abroad.

Healy's determination was evident. He worked diligently, saving money from his commissions. His early portraits from this Boston period, while perhaps not yet displaying the full maturity of his later work, showed promise in capturing likeness and character, laying the groundwork for his future successes.

The Parisian Sojourn: Training and Early Recognition

In 1834, at the age of twenty-one, George Healy embarked for Europe, with Paris as his primary destination. This was a common path for ambitious American artists of the period, as Paris was then the undisputed center of the Western art world, home to prestigious academies and influential masters. Healy enrolled in the atelier of Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, a prominent painter who had himself been a pupil of the great Neoclassical master Jacques-Louis David. Gros was renowned for his large-scale historical paintings, often depicting Napoleonic battles, as well as his portraits. Under Gros, Healy would have received rigorous training in drawing, anatomy, and composition, adhering to the academic standards of the time.

Healy also reportedly studied with Thomas Couture, another highly respected French academic painter and teacher, whose most famous work, Romans of the Decadence, caused a sensation at the Paris Salon. Couture's emphasis on solid draughtsmanship and thoughtful composition would have further refined Healy's technique. The influence of these French masters is evident in Healy's mature style, characterized by its strong drawing, balanced compositions, and often a certain gravitas, even in his portraits.

During his time in Paris, Healy began to gain recognition. He exhibited at the Paris Salon, a critical venue for artists seeking to establish their reputations. He received a third-class medal at the Salon of 1840, a significant early honor. His skill in portraiture quickly attracted a distinguished clientele, including members of the French aristocracy and American expatriates. One of his most important early patrons was King Louis Philippe I of France, the "Citizen King." This royal patronage significantly boosted Healy's career, leading to numerous commissions from the French court and nobility.

A Transatlantic Career: Portraits of Prominence

Healy's success in Paris did not confine him to Europe. He developed a truly transatlantic career, dividing his time between France, England, and the United States. He became particularly renowned for his portraits of eminent political figures. In America, he painted a remarkable array of presidents, including John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, John Tyler, James K. Polk, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, James Buchanan, Abraham Lincoln, and Ulysses S. Grant. His portrait of Abraham Lincoln, particularly the thoughtful and somewhat melancholic depiction, is among his most famous works and is considered an iconic image of the president.

His ability to secure sittings with such a distinguished roster speaks volumes about his reputation and his diplomatic skills. These presidential portraits were not mere likenesses; Healy often sought to convey the weight of office and the personality of the leader. For instance, his portrait of Franklin Pierce captures a sense of dignity and quiet strength. He also painted other leading American statesmen, such as Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun, effectively creating a visual gallery of the nation's mid-19th-century leadership.

In Europe, beyond his work for King Louis Philippe, Healy painted other members of royalty and aristocracy. His sitters included Pope Pius IX, a commission that further underscored his international standing. He was adept at navigating the social circles of the elite, and his studio became a meeting place for influential individuals. His style, while grounded in French academicism, possessed a directness and a lack of excessive flattery that appealed to many of his American subjects, while his technical polish satisfied European tastes. He was a contemporary of other notable portraitists like the German Franz Xaver Winterhalter, who was also famed for his depictions of European royalty, though Healy's style often had a more robust, less idealized quality, particularly with his male sitters.

Mastering the Grand Historical Narrative

While primarily known as a portraitist, George Peter Alexander Healy also undertook ambitious historical paintings. These large-scale compositions allowed him to showcase his skills in figure arrangement, dramatic narrative, and historical detail, aligning with the grand manner favored by his teacher Antoine-Jean Gros and other academic painters like Paul Delaroche or Horace Vernet.

One of his most significant historical works is Webster's Reply to Hayne. Completed in 1851, this monumental canvas depicts the famous 1830 Senate debate between Daniel Webster of Massachusetts and Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina over states' rights and nullification. The painting is a tour de force of group portraiture, featuring an astonishing 130 individual likenesses of senators, dignitaries, and spectators present at the debate. Healy meticulously researched the event and the appearances of the figures involved. The work, now housed in Faneuil Hall in Boston, is not only a historical document but also a testament to Healy's ambition and his ability to manage complex compositions.

Another important historical painting is Franklin Urging the Claims of the American Colonies Before Louis XVI, completed in 1855. This work depicts Benjamin Franklin presenting the American cause at the French court. It showcases Healy's understanding of historical costume and setting, and his ability to create a dramatic and engaging scene. This painting was exhibited at the Paris International Exposition of 1855, where it received a silver medal, further cementing Healy's reputation on the international stage. These historical works demonstrate Healy's versatility and his engagement with significant national and international themes.

The Chicago Years: A Pillar of the Art Community

In 1855, seeking new opportunities and perhaps a more settled base for his growing family (he had married Louisa Phipps in 1839 and they eventually had several children), Healy moved to Chicago. At this time, Chicago was a rapidly growing city, eager to establish itself as a cultural center. Healy quickly became a leading figure in the city's nascent art scene.

He was instrumental in the founding of the Chicago Academy of Design in 1866, which would later evolve into the renowned Art Institute of Chicago. His presence and reputation lent considerable prestige to the young institution. Healy was incredibly prolific during his Chicago years, reportedly painting around 100 portraits annually. His sitters included the city's burgeoning elite – businessmen, civic leaders, and their families. He maintained a studio in the Crosby Opera House building for a time.

Despite the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, which devastated the city, Healy continued to be a prominent artistic force. Many of his works, and those of other artists, were tragically lost in the fire, but the city's cultural institutions, with figures like Healy providing leadership, were determined to rebuild.

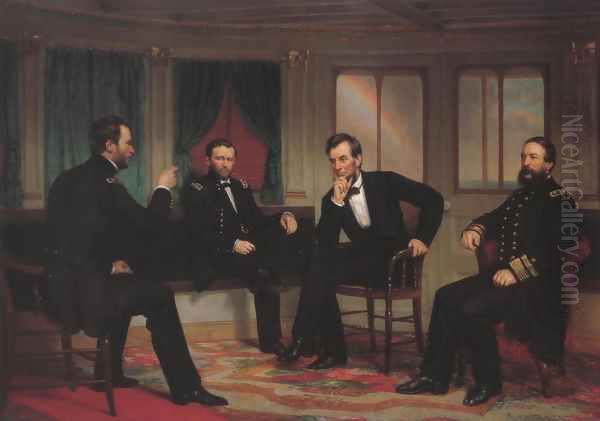

One of his most celebrated works from this later period is The Peacemakers, completed in 1868. This painting depicts a crucial council of war held aboard the steamer River Queen at City Point, Virginia, in March 1865, near the end of the American Civil War. The figures are President Abraham Lincoln, General Ulysses S. Grant, General William Tecumseh Sherman, and Admiral David Dixon Porter. The painting captures a moment of solemn discussion and strategic planning. Healy's portrayal of Lincoln, in particular, is noted for its humanity and weariness. The Peacemakers is considered a significant historical painting and a highlight of Healy's career, demonstrating his continued ability to tackle important national subjects with skill and insight.

Artistic Style and Technique

George Peter Alexander Healy's artistic style was firmly rooted in the 19th-century academic tradition, heavily influenced by his French training under masters like Antoine-Jean Gros and Thomas Couture. His work is characterized by strong, accurate drawing, a hallmark of academic practice. He paid close attention to anatomical correctness and the clear delineation of form, providing his figures with a sense of solidity and presence.

His color palette was generally rich and refined, though often subdued in his male portraits to convey sobriety and dignity. He was skilled in rendering textures, from the sheen of silk and satin in his female portraits to the rougher wool of a statesman's coat. His handling of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) was adept, used to model forms effectively and often to create a focal point, drawing the viewer's eye to the face of the sitter. His brushwork, while generally smooth and polished in the academic manner, could also exhibit a certain vigor, particularly in his less formal studies or in the rendering of backgrounds.

Healy was a master of capturing a likeness, a fundamental requirement for a successful portraitist. However, his best works go beyond mere physical resemblance. He possessed a psychological acuity, an ability to suggest the character, intellect, or emotional state of his subjects. This is evident in the thoughtful expression of Lincoln, the commanding presence of Webster, or the regal bearing of King Louis Philippe. While not an innovator in the sense of challenging artistic conventions like the later Impressionists (a movement he reportedly disliked), Healy perfected the established portraiture style of his time. His approach was direct and often unidealized, particularly with his American subjects, which lent his portraits a sense of authenticity and strength. He could be compared to other American contemporaries like Daniel Huntington, who also painted portraits and historical scenes, or Eastman Johnson, though Johnson leaned more towards genre scenes.

Later Years, European Return, and Enduring Legacy

After many productive years in Chicago, Healy returned to Europe in 1867, residing mainly in Paris and Rome for over two decades. He continued to paint and exhibit, maintaining his international connections. During this period, artistic tastes in Europe were shifting dramatically with the rise of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Healy, however, remained committed to his academic style. His disapproval of Impressionism, shared by many artists of his generation trained in the traditional academies, reflected his adherence to the values of careful draughtsmanship and finished surfaces. Figures like Claude Monet or Edgar Degas represented a radical departure from these principles.

He eventually returned to Chicago in 1892. George Peter Alexander Healy passed away in Chicago on June 24, 1894, at the age of 80 (often cited as 81 due to his upcoming birthday). He left behind an immense body of work, estimated at over 2,000 paintings, the majority of which are portraits.

His legacy is significant. As a portraitist, he created an invaluable visual archive of the leading personalities of the 19th century on both sides of the Atlantic. His paintings are held in major museums and collections, including the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C., the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Louvre in Paris. He was an elected honorary member of the National Academy of Design in New York, a testament to his standing among his peers.

Healy's contribution also lies in his role as a cultural bridge between America and Europe, and in his efforts to foster art institutions in the United States, particularly in Chicago. While artistic styles have evolved, the historical importance and technical skill evident in Healy's work ensure his enduring place in the annals of American art history. He was a contemporary of other American artists who also spent time abroad, such as Hiram Powers in sculpture or painters like John Singer Sargent (though Sargent's major impact came slightly later and represented a more painterly, modern approach to portraiture).

Healy and His Contemporaries: A Web of Influences

George Healy's career was interwoven with many of the prominent artistic figures of his time. His early encouragement from Thomas Sully (1783-1872) was pivotal. Sully, known for his graceful portraits influenced by British masters like Sir Thomas Lawrence, represented an earlier generation of American portraiture that valued elegance and a certain romantic sensibility.

In Paris, his teachers were central. Baron Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835) was a direct link to the Neoclassicism of Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), though Gros himself infused his historical epics with a Romantic dynamism. Gros's influence would have instilled in Healy a respect for grand compositions and historical subjects. Thomas Couture (1815-1879), another of Healy's mentors, was a highly influential academic teacher whose pupils included Édouard Manet (1832-1883), though Manet famously broke away from Couture's more traditional methods. Couture's emphasis on technique and thoughtful execution resonated with Healy's own meticulous approach.

In the realm of portraiture, Healy operated in a world populated by other skilled practitioners. In America, figures like Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828) had set a high bar for presidential portraiture, and Healy, in many ways, continued this tradition into the mid-19th century. Other American contemporaries included Chester Harding (1792-1866), known for his straightforward and robust portraits, and Rembrandt Peale (1778-1860), who, like Healy, painted many prominent figures. Daniel Huntington (1816-1906) was a close contemporary whose career paralleled Healy's in some respects, as he also painted historical scenes and numerous portraits, and was long associated with the National Academy of Design.

In Europe, Healy's work for royalty can be seen in the context of court painters like Franz Xaver Winterhalter (1805-1873), who was a favorite of Queen Victoria and Emperor Napoleon III, known for his dazzling and often flattering depictions of European aristocracy. While Healy's style was perhaps less overtly glamorous, his ability to secure such commissions placed him in a similar sphere. The French academic scene also included painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) or Paul Delaroche (1797-1856), who specialized in historical and Orientalist scenes, upholding the academic values Healy himself espoused. Even the great Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) and the Neoclassical titan Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) were active during parts of Healy's career, representing the dominant, often competing, artistic forces in Paris. Healy's adherence to a more straightforward, if highly skilled, academic realism in his portraiture allowed him to carve out a distinct and highly successful niche.

Conclusion: An Enduring Chronicler of an Age

George Peter Alexander Healy was more than just a painter of faces; he was a chronicler of an era. His prolific output and the prominence of his sitters provide an unparalleled visual record of 19th-century leadership and society in both America and Europe. From the halls of Congress to the courts of kings, Healy moved with an assurance born of his talent and professionalism. His dedication to his craft, his ambition, and his ability to connect with and capture the essence of his subjects cemented his status as one of the preeminent portraitists of his day. While he may not have been an avant-garde revolutionary, his mastery of the academic tradition and his insightful portrayals have ensured that his work remains relevant and valued, offering us a window into the personalities and power structures of a transformative century.