Enoch Wood Perry Jr. (1831-1915) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century American art. His career, spanning from the antebellum South to the bustling art scenes of Europe and New York, and westward to California and Hawaii, reflects the dynamic cultural and geographical transformations of his time. A versatile painter, Perry excelled in portraiture, genre scenes, and landscapes, leaving behind a body of work that captures the diverse facets of American life and its natural beauty. His artistic journey was marked by rigorous European training, influential encounters with leading artists of his day, and a keen observational eye that he applied to a wide array of subjects.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1831, Enoch Wood Perry Jr.'s early life set the stage for a future deeply immersed in the arts. The Perry family relocated to New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1844, when Enoch was thirteen. This move to the vibrant, culturally rich Southern city undoubtedly exposed the young Perry to a different societal fabric and a unique visual environment. It was in New Orleans that he received his foundational education in public schools.

Even in his youth, Perry exhibited a strong passion for art and an unwavering determination to pursue it professionally. Financial constraints were an early hurdle, but his resolve was formidable. To fund his artistic ambitions, particularly his dream of studying in Europe, Perry took on work in a grocery store. This period of diligent saving underscores his early commitment and the practical sacrifices he was willing to make to achieve his artistic goals. This dedication would become a hallmark of his long and productive career.

European Sojourn: Düsseldorf and Paris

By 1852, Perry had accumulated sufficient funds to embark on his European artistic pilgrimage, a common path for ambitious American artists of the era seeking advanced training. His first major stop was Düsseldorf, Germany, a city then renowned for its influential art academy, the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. From 1852 to 1853, he studied under the tutelage of Emmanuel Leutze, a German-American historical painter of great renown. Leutze, celebrated for iconic works such as Washington Crossing the Delaware, was a pivotal figure in the Düsseldorf school, known for its meticulous detail, narrative clarity, and often grand historical or allegorical themes. Perry's time with Leutze would have instilled in him a disciplined approach to drawing and composition. Other American artists who studied in Düsseldorf around this period, though not necessarily direct contemporaries in Leutze's studio, included Albert Bierstadt and Worthington Whittredge, who also absorbed the school's emphasis on precision and dramatic effect.

Following his studies in Düsseldorf, Perry moved to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world in the mid-19th century. There, he entered the atelier of Thomas Couture, a highly respected painter and influential teacher. Couture's own work, such as his celebrated Romans of the Decadence, represented a path between academic tradition and emerging realist tendencies. His teaching methods encouraged individuality and a more expressive handling of paint, a contrast to the tighter finish often associated with Düsseldorf.

In Couture's studio, Perry found himself among a cohort of talented young artists, some of whom would become luminaries of modern art. His classmates reportedly included Édouard Manet, a future pioneer of Impressionism, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, who would become a leading Symbolist painter known for his serene, mural-like compositions. Some accounts also suggest Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was a fellow student, though Lautrec's primary period of study was later and under different masters; it's possible Perry encountered him if he returned to Paris or if Couture's teaching spanned a very long period with diverse student intakes. Regardless, the intellectual ferment and artistic innovation of Paris, and the association with such forward-thinking peers, would have profoundly broadened Perry's artistic horizons. He also spent time studying in Rome and Venice, further immersing himself in the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance and the rich artistic traditions of Italy.

Venetian Interlude and Diplomatic Service

Perry's connection with Italy, particularly Venice, deepened significantly when he was appointed United States Consul to Venice, a position he held from 1856 to 1858. This diplomatic role provided him with a unique vantage point and financial stability, allowing him to continue his artistic pursuits in one of Europe's most picturesque cities. Venice, with its luminous light, shimmering canals, and rich artistic heritage, had long captivated artists, from Renaissance masters like Titian and Veronese to later view painters such as Canaletto and Francesco Guardi, and more contemporary figures like J.M.W. Turner.

During his consulship, Perry actively painted, capturing the unique atmosphere of the city. His Venetian landscapes gained recognition, and his works from this period were exhibited, contributing to his growing reputation. This experience not only enriched his artistic palette but also provided him with a platform on the international stage, blending his diplomatic duties with his burgeoning art career. The interplay of light and water, a defining characteristic of Venetian painting, likely influenced his subsequent landscape work.

Return to America: New Orleans and the Antebellum South

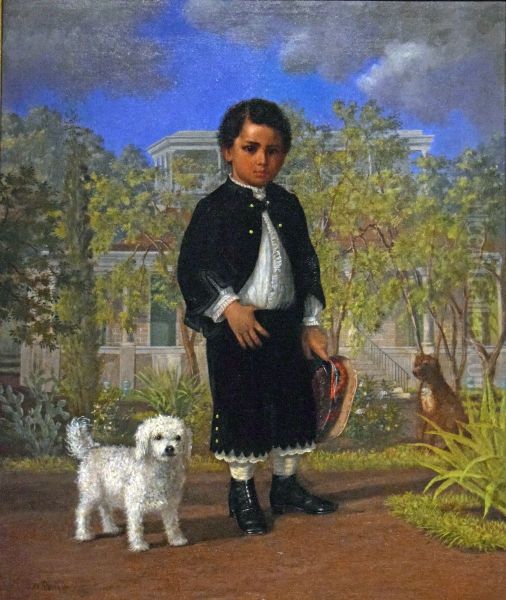

Upon returning to the United States around 1858 or 1859, Perry initially established a studio in New Orleans, the city of his upbringing. He quickly made a name for himself as a painter of "social portraits," catering to the prominent families and individuals of the region. His European training and refined technique were well-suited to the demands of Southern portraiture, which often emphasized elegance and social standing.

One of his most notable commissions from this period was a portrait of Jefferson Davis, who would soon become the President of the Confederate States of America. This painting, along with others depicting Southern scenes and figures, cemented Perry's reputation in the region. He also undertook ambitious historical compositions, such as The Signing of the Ordinance of Secession of Louisiana (1861), a work that captured a pivotal moment in the state's history leading up to the Civil War. These works demonstrate his engagement with the significant political and social currents of his time. His style in portraiture would have been compared to other American portraitists of the era, though his genre work would eventually become more prominent.

The Civil War and Western Vistas

The outbreak of the American Civil War (1861-1865) profoundly disrupted life across the nation, and the art world was no exception. With the South embroiled in conflict, Perry, like many artists, sought new opportunities and perhaps refuge elsewhere. He relocated to California, a state that was rapidly developing and offered fresh landscapes and patronage.

In California, Perry continued to paint portraits but also turned his attention to the majestic scenery of the American West. A significant moment during this period was his sketching trip to the Yosemite Valley in the company of Albert Bierstadt. Bierstadt, already a celebrated painter of the Hudson River School's second generation (often termed the Rocky Mountain School), was known for his grandiose depictions of Western landscapes. Their joint expedition to Yosemite, a place of breathtaking natural beauty that was increasingly capturing the national imagination, would have been a formative experience for Perry. He, like Bierstadt, Thomas Moran, and Thomas Hill, contributed to the visual iconography of the American West, showcasing its sublime and untamed character to audiences back East and in Europe.

Perry's travels were not limited to California. He also spent time in Utah, where he continued to paint portraits of prominent figures, including Brigham Young. His engagement with the artistic community in Utah was substantial; he played a key role in founding the Deseret Art Union in 1865, an early effort to promote art and art education in the territory. This initiative highlights his commitment to fostering artistic culture beyond the established art centers.

Hawaiian Interlude: Capturing Paradise

In the mid-1860s, Perry embarked on another significant journey, this time to the Hawaiian Islands (then often known as the Sandwich Islands). He spent approximately two years there, from around 1864 to 1866, captivated by the lush tropical landscapes and the unique culture of the Hawaiian people. This period resulted in a remarkable series of paintings that are among the earliest and most important depictions of Hawaii by a professionally trained American artist.

His Hawaiian works include stunning landscapes such as Manoa Valley from Waikiki, Diamond Head, and views of volcanic phenomena. He also painted portraits of Hawaiian royalty and everyday scenes, offering a valuable visual record of the islands before widespread Westernization. These paintings are characterized by their vibrant color, attention to botanical detail, and sensitivity to the atmospheric conditions of the tropics. Perry's Hawaiian oeuvre stands alongside the work of other artists who depicted the Pacific, such as Jules Tavernier (who also painted in Hawaii later) and Titian Ramsay Peale (who documented Pacific flora and fauna on earlier expeditions). The Bishop Museum in Honolulu now holds a significant collection of Perry's Hawaiian paintings, underscoring their historical and artistic importance.

Later Years in New York and Legacy

After his extensive travels, Enoch Wood Perry Jr. eventually settled in New York City, which by the late 19th century had become the undisputed center of the American art world. He established a studio there, reportedly taking over the space previously occupied by his friend, the artist John Francis Waterhouse. New York provided him with a vibrant artistic community, exhibition opportunities, and access to patrons.

He became an active participant in the New York art scene, regularly exhibiting his works at prestigious venues such as the National Academy of Design. His talent was recognized by his peers, and he was elected an Associate National Academician (ANA) in 1868 and a full National Academician (NA) in 1869. This honor signified his established position within the American art establishment.

Perry continued to paint a variety of subjects, but he became particularly well-known for his genre scenes, which often depicted rural American life with a sense of nostalgia and quiet dignity. These works resonated with a public that was grappling with rapid industrialization and urbanization, offering glimpses of a seemingly simpler, more virtuous past. He also continued to paint portraits and occasional landscapes.

Enoch Wood Perry Jr. died in New York City in 1915 at the age of 84, leaving behind a rich and varied artistic legacy. His long career witnessed immense changes in American society and art, and his work reflects a journey through these transformations.

Artistic Style and Influences

Enoch Wood Perry Jr.'s artistic style was an amalgam of his diverse training and experiences. His early studies in Düsseldorf under Emmanuel Leutze instilled a foundation of strong draftsmanship, careful composition, and a penchant for narrative detail. This is evident in the clarity and precision found in many of his works, particularly his portraits and historical scenes.

His time with Thomas Couture in Paris exposed him to a more painterly approach, encouraging bolder brushwork and a greater emphasis on capturing the immediate sensation of light and form. Couture's influence can be seen in the more fluid handling of paint in some of Perry's genre scenes and landscapes.

Upon his return to America, Perry's style also showed an affinity with certain aspects of the Hudson River School, particularly in his Western and Hawaiian landscapes. Like artists such as Frederic Edwin Church or Sanford Robinson Gifford, he demonstrated a keen interest in the effects of light and atmosphere and a desire to capture the specific character of the American (and Hawaiian) environment. However, his primary focus often leaned more towards human activity within these landscapes.

In his genre paintings, Perry shared thematic concerns with contemporaries like Eastman Johnson and Winslow Homer. These artists depicted scenes of everyday American life, often rural, with an eye for authentic detail and character. Perry's genre works are typically characterized by their careful observation, warm sentiment, and clear storytelling. He often imbued his scenes with a sense of quiet dignity and sometimes a gentle nostalgia, reflecting a common 19th-century yearning for pastoral ideals. His use of color was generally rich and descriptive, contributing to the realism and appeal of his compositions.

Key Works and Their Significance

Several works stand out in Enoch Wood Perry Jr.'s extensive oeuvre, highlighting his skill across different genres.

The True American (1875, The Metropolitan Museum of Art): This is perhaps Perry's most famous genre painting. It depicts an African American man reading a newspaper, likely with a title or headline alluding to the theme of American identity in the post-Civil War era. The painting is noted for its sensitive portrayal and its engagement with contemporary social issues. It showcases Perry's skill in character study and his ability to create a narrative with quiet power.

Talking It Over (1872): This genre scene, depicting two farmers in conversation within a rustic barn interior, is characteristic of Perry's nostalgic portrayals of rural life. The detailed rendering of the figures, their tools, and the barn setting, combined with the warm lighting, creates an atmosphere of authenticity and quiet contemplation. Such works appealed to a public increasingly removed from agrarian life, offering an idealized vision of American values. This painting shares thematic similarities with works by Winslow Homer from the same period, who also explored themes of rural labor and community.

Signing the Ordinance of Secession of Louisiana (1861): This historical painting captures a critical moment in American history. While the original may be lost or its location unknown, studies or related works attest to Perry's ambition in tackling large-scale historical subjects, a skill honed under Leutze. Such paintings served as important visual records and interpretations of significant national events.

Portraits of Jefferson Davis and Brigham Young: These portraits of influential and controversial figures demonstrate Perry's skill as a portraitist and his engagement with prominent personalities of his time. Such commissions were crucial for an artist's reputation and livelihood.

Hawaiian Landscapes and Portraits (e.g., Manoa Valley from Waikiki, Diamond Head, Prince of Hawaii): This body of work is particularly significant for its early and skilled depiction of the Hawaiian Islands. These paintings are valuable not only for their artistic merit, showcasing Perry's ability to capture the unique light and lushness of the tropics, but also as historical documents of a culture and landscape undergoing significant change.

Far Scene, Boy by a Well (1864): This work likely reflects his landscape and genre interests, combining human elements with a broader natural setting, typical of his ability to merge narrative with scenic depiction.

These works, among many others, illustrate Perry's versatility and his consistent ability to capture the essence of his subjects, whether they were people, places, or moments in everyday life.

Perry and His Contemporaries

Enoch Wood Perry Jr.'s career intersected with many of the leading artistic figures and movements of his time. His European education placed him in direct contact with influential teachers like Emmanuel Leutze and Thomas Couture, and fellow students such as Édouard Manet and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. These interactions undoubtedly shaped his artistic development and worldview.

In America, his association with Albert Bierstadt during their Yosemite expedition connects him to the grandeur of the Hudson River School and the exploration of the American West. His genre paintings invite comparison with those of Winslow Homer, Eastman Johnson, and George Caleb Bingham, who were also chroniclers of American life. While Homer's work often possessed a starker realism and psychological depth, Perry's genre scenes shared a common interest in rural themes and narrative clarity.

His portraiture can be seen in the context of other 19th-century American portraitists, though perhaps not reaching the international fame of a later figure like John Singer Sargent or the penetrating psychological insight of Thomas Eakins. Nevertheless, Perry provided capable and often insightful likenesses for his sitters.

His involvement in founding the Deseret Art Union in Utah shows a commitment to artistic community building, a spirit shared by many artists who sought to establish cultural institutions in a growing nation. His long tenure as a National Academician placed him within the established art circles of New York, alongside figures like Frederic Edwin Church, Sanford Robinson Gifford, and other prominent members of the National Academy of Design. He also knew the marine and landscape painter John Francis Waterhouse, whose New York studio he later occupied. The broader artistic environment would have included influences from movements like the Barbizon School, whose landscape aesthetics were filtering into American art through artists like William Morris Hunt (another Couture student) and George Inness.

Collections and Enduring Presence

Enoch Wood Perry Jr.'s works are held in the collections of numerous prestigious American museums, a testament to his historical and artistic significance. These institutions include:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Home to The True American.

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia

The Art Institute of Chicago

The Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii: Holding a key collection of his Hawaiian works.

Louisiana State University Museum of Art, Baton Rouge

The Oakland Museum of California

The Buffalo AKG Art Museum (formerly the Albright-Knox Art Gallery/Buffalo Fine Arts Academy)

National Academy of Design, New York

His presence in these collections ensures that his contributions to American art continue to be studied and appreciated. While he may not be as universally recognized as some of his most famous contemporaries, Perry's diverse body of work offers invaluable insights into the artistic currents, cultural landscapes, and historical narratives of 19th-century America. His journey from Boston to New Orleans, through the art academies of Europe, across the American West, and to the shores of Hawaii, reflects a life dedicated to capturing the world around him with skill, sensitivity, and an enduring artistic vision.