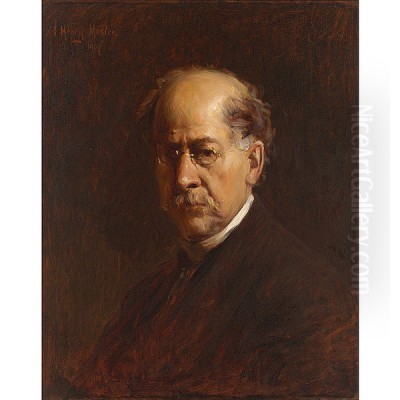

Henry Mosler stands as a significant figure in late 19th and early 20th-century American art, a painter whose career bridged the artistic traditions of the Old World with the burgeoning cultural landscape of the New. Born in Tropplowitz, Silesia (then Prussia, now Opawka, Poland), on June 6, 1841, into a Jewish family, Mosler's life and art were shaped by immigration, war, extensive European training, and a keen observational eye for human experience. His journey from a young apprentice in the American Midwest to an acclaimed artist in the salons of Paris is a testament to his talent, perseverance, and ability to capture the spirit of his times.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings in America

The Mosler family, like many European families in the mid-19th century, sought new opportunities across the Atlantic. In 1849, when Henry was just eight years old, they immigrated to New York City. The bustling metropolis was a stark contrast to their Silesian homeland, but the family soon moved westward, settling in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1851. Cincinnati, at that time, was a vibrant and growing city, often referred to as the "Queen City of the West," with a developing artistic community.

Mosler's father, Gustav Mosler, was a lithographer, and his mother, Sophie Weiner Mosler, reportedly engaged in wood engraving. This familial immersion in the graphic arts undoubtedly nurtured young Henry's nascent artistic inclinations. He demonstrated an early aptitude for drawing and received his initial artistic instruction from local artists. By the age of ten, he was already taking drawing lessons, and his talent quickly became apparent.

His formal artistic journey began in earnest when, at the young age of 15, he secured a position as an illustrator and cartoonist for The Omnibus, a comic weekly paper in Cincinnati. This early experience in illustration honed his skills in narrative composition and character depiction, elements that would become hallmarks of his later genre paintings. It was during this period, from 1859 to 1861, that Mosler sought more structured training under James Henry Beard, a prominent Cincinnati painter known for his portraits and animal subjects. Beard's guidance provided Mosler with a solid foundation in the fundamentals of painting, including anatomy, composition, and color theory.

The Crucible of War: A Special Artist for Harper's Weekly

The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 dramatically altered the course of many lives, including Henry Mosler's. In 1862, his artistic talents found a new, urgent purpose when he was engaged by Harper's Weekly, one of the leading illustrated newspapers of the era. He served as a "special artist" or war correspondent, tasked with documenting the Western Campaign. This role was fraught with danger but offered an unparalleled opportunity to witness and record history in the making.

Embedded with the Union Army, Mosler sketched scenes of camp life, troop movements, and the grim realities of battle in Kentucky and Tennessee. His illustrations, once engraved, provided the public with vivid visual accounts of the war, complementing the written dispatches. He documented significant events, including the campaigns around the Green River and the Battle of Perryville. This experience was formative, forcing him to work quickly and accurately under challenging conditions, further developing his observational skills and his ability to capture dramatic human moments. His work for Harper's Weekly placed him alongside other notable illustrators of the conflict, such as Winslow Homer and Thomas Nast, who also contributed to the visual record of the war. The immediacy and narrative demands of wartime illustration undoubtedly influenced his later preference for genre scenes that told compelling stories.

European Sojourns and Academic Training

Following his service in the Civil War, Mosler, like many ambitious American artists of his generation, recognized the necessity of European study to refine his technique and broaden his artistic horizons. In 1863, with funds likely supplemented by his work for Harper's, he embarked on his first extended trip to Europe. His primary destination was Düsseldorf, Germany, home to the renowned Royal Academy of Fine Arts. The Düsseldorf Academy was a magnet for international students, particularly Americans, admired for its rigorous curriculum emphasizing meticulous draftsmanship, detailed realism, and narrative clarity, especially in historical and genre painting.

The Düsseldorf Influence

In Düsseldorf, Mosler studied for nearly three years, from 1863 to late 1865 or early 1866. He initially enrolled in classes under Heinrich Mücke, a history painter, and later studied with Albert Kindler, who was known for his genre scenes. The Düsseldorf School's emphasis on precise drawing, careful composition, and often sentimental or anecdotal subject matter left a lasting imprint on Mosler's style. He absorbed the techniques of careful finish and detailed rendering that characterized the school. Other American artists who had studied or were studying in Düsseldorf around this period included Albert Bierstadt, Emanuel Leutze (famous for Washington Crossing the Delaware), and Eastman Johnson, contributing to a significant transatlantic artistic exchange. The school's narrative focus resonated with Mosler's own inclinations, evident from his earlier work as an illustrator.

After his intensive studies in Düsseldorf, Mosler traveled to Paris in 1865. The French capital was rapidly becoming the epicenter of the art world, offering a different, perhaps more progressive, artistic environment than Düsseldorf. In Paris, he sought out further instruction, studying for approximately six months with Ernest Hébert, an academic painter known for his elegant portraits and romanticized genre scenes, often with Italian peasant themes. Hébert's influence may have introduced a softer, more atmospheric quality to Mosler's work, complementing the stricter realism of the Düsseldorf school.

Return to Cincinnati and Growing Reputation

Mosler returned to Cincinnati in 1866, his European training having significantly enhanced his skills and artistic vision. He established a studio and began to build his reputation, primarily as a portrait painter, a common path for artists seeking to establish a steady income. He also painted genre scenes and landscapes, reflecting the breadth of his training. During this period, he became an active member of Cincinnati's artistic community and painted one of his notable early works, The Plum Street Temple (1866), a depiction of the interior of the Isaac M. Wise Temple, a significant commission that highlighted his connection to the local Jewish community. His work from this era demonstrated a growing technical proficiency and a developing narrative sense.

Parisian Triumphs and Breton Scenes

Despite his growing success in Cincinnati, the allure of Paris, the undisputed art capital of the world, remained strong. In 1874, Mosler returned to Europe, this time with his wife, Sara Cahn, whom he had married in 1869. He initially spent three years in Munich, where he studied under Carl Theodor von Piloty, a leading figure in the Munich School of historical painting, and also received guidance from Wilhelm von Diez. The Munich School, like Düsseldorf, emphasized strong draftsmanship and realism but often with a bolder brushwork and a greater interest in the effects of light and shadow, influenced by Old Masters like Rembrandt.

In 1877, Mosler and his family moved to Paris, which would be his primary base for nearly two decades, until 1894. This period marked the zenith of his career and international recognition. He quickly immersed himself in the Parisian art world, exhibiting regularly at the prestigious Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The Salon was the most important venue for an artist to gain recognition and patronage.

It was in France that Mosler found one of his most enduring subjects: the peasant life of Brittany. This rugged, culturally distinct region of northwestern France, with its traditional costumes, customs, and deeply rooted Catholic faith, fascinated many artists of the period, including French painters like Jules Breton and Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret. These artists, part of a broader movement often termed Naturalism or Rural Naturalism, sought to depict peasant life with a degree of realism, though often tinged with sentimentality or a sense of the picturesque. Mosler was drawn to the narrative possibilities and the perceived authenticity of Breton life.

His breakthrough came with the painting Le Retour (The Return), also known as The Prodigal's Return, exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1879. This large, emotionally charged genre scene depicted a Breton family welcoming back a wayward son. The painting was a critical success, praised for its technical skill, narrative power, and sympathetic portrayal of its subjects. In a remarkable achievement for an American artist, Le Retour was purchased by the French government for the Musée du Luxembourg, which housed contemporary art. This was the first painting by an American artist to be so honored, catapulting Mosler to international fame. He received an honorable mention at the Salon for this work.

Following this triumph, Mosler continued to produce significant works, many of which focused on Breton themes. The Wedding Feast in Brittany (1880s), The Last Sacrament (c. 1884), and Visiting the Sick Child (c. 1889) are exemplary of his work from this period. These paintings are characterized by their meticulous detail, careful composition, and often poignant or sentimental narratives. He excelled at capturing the textures of fabrics, the play of light in interiors, and the expressive gestures and faces of his figures. His success at the Salon continued; he was awarded a third-class medal in 1885 and a silver medal at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris in 1889. He also received a gold medal at the International Exhibition in Vienna in 1873, prior to his major Paris successes, and was made a Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur by the French government in 1892, and an Officier d'Académie.

Mastering Genre: Key Works and Themes

Henry Mosler's oeuvre is rich with narrative genre scenes that explore universal human experiences through the lens of specific cultural contexts, primarily Breton peasant life and, to a lesser extent, American domestic scenes.

Le Retour (The Prodigal's Return) (1879): This seminal work depicts the emotional reunion of a prodigal son with his Breton family. The interior setting is meticulously rendered, with details of rustic furniture and clothing contributing to the scene's authenticity. The figures' expressions and gestures convey a range of emotions – relief, forgiveness, and familial love. The painting's success lay in its ability to resonate with a wide audience through its universal theme, presented with academic polish and heartfelt sentiment.

The Wedding Feast in Brittany (c. 1880s): This painting captures the communal joy and traditional rituals of a Breton wedding. Mosler skillfully orchestrates a complex multi-figure composition, detailing the festive attire of the guests, the laden tables, and the celebratory atmosphere. Such works provided viewers with a glimpse into a way of life perceived as both picturesque and virtuous.

The Last Sacrament (c. 1884): A more somber and deeply religious theme, this painting portrays a priest administering the final rites to a dying individual in a humble Breton cottage, surrounded by grieving family members. The scene is imbued with a quiet solemnity, and Mosler's handling of light, often emanating from a single window or candle, enhances the spiritual and emotional gravity of the moment.

Visiting the Sick Child (c. 1889): This work exemplifies Mosler's ability to evoke empathy. A mother and perhaps a local healer or concerned neighbor attend to a sick child in a modest interior. The tender concern on the figures' faces and the vulnerability of the child create a poignant narrative that appealed to Victorian sensibilities.

Plum Street Temple (1866): An earlier work, but significant for its depiction of a prominent Cincinnati landmark and its connection to Mosler's Jewish heritage. The painting showcases the ornate Moorish Revival interior of the temple, demonstrating Mosler's skill in architectural rendering and his ability to capture the atmosphere of a specific place.

Just Moved (c. 1870): This American genre scene depicts a family in the midst of settling into a new home. The clutter of belongings and the figures' expressions suggest the weariness and perhaps the hope associated with relocation. It demonstrates Mosler's interest in everyday American life before his extended focus on European subjects. His handling of light and shadow in this piece is particularly noteworthy, creating a sense of domestic realism.

These works, among others, highlight Mosler's commitment to storytelling, his meticulous attention to detail, and his ability to convey emotion. While his style remained largely academic, resisting the more radical innovations of Impressionism (then championed by artists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas) or Post-Impressionism, his paintings found favor with a public that appreciated skillful execution and relatable, often sentimental, narratives.

Artistic Style and Technique

Henry Mosler's artistic style was firmly rooted in the academic traditions of the 19th century, particularly those of the Düsseldorf and French academic schools. His work is characterized by:

Meticulous Draftsmanship: A hallmark of his training, Mosler's paintings exhibit precise drawing and clearly defined forms. Figures are rendered with anatomical accuracy, and details of costume, setting, and objects are carefully delineated.

Narrative Clarity: Mosler was a storyteller in paint. His compositions are carefully constructed to convey a specific narrative or emotional moment. He used gesture, facial expression, and the arrangement of figures and objects to guide the viewer's understanding of the scene.

Detailed Realism: He paid close attention to the textures of materials – the rough wool of a peasant's coat, the smooth sheen of polished wood, the delicate lace of a bridal veil. This detailed realism added to the perceived authenticity of his scenes.

Emphasis on Sentiment: Many of Mosler's paintings evoke strong emotions, often leaning towards sentimentality. Themes of family, faith, love, loss, and community are central to his work, appealing to the prevailing tastes of the Victorian era.

Skillful Use of Light and Shadow (Chiaroscuro): Particularly in his interior scenes, Mosler demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of light. He often used a single light source, such as a window or a lamp, to create dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, heightening the mood and focusing attention on key elements of the composition. This was a technique he likely refined during his time in Munich.

Rich Color Palette: While not as vibrant as the Impressionists, Mosler employed a rich and varied color palette, using color to enhance the realism of his scenes and contribute to their emotional tone.

Academic Finish: His paintings typically have a smooth, polished surface, with brushstrokes largely invisible, a characteristic of academic painting that aimed for a high degree of finish and illusionism.

While he was aware of the emerging modernist movements, Mosler remained committed to the narrative and technical conventions of academic art. His contemporaries in America who also pursued academic and realist styles, often with European training, included figures like Thomas Eakins, known for his unflinching realism, and William Merritt Chase, who, while more influenced by Impressionism later in his career, also had strong academic roots. In Europe, artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme and William-Adolphe Bouguereau represented the pinnacle of French academic painting, a tradition within which Mosler found considerable success.

Return to America and Later Years

In 1894, after two decades abroad, Henry Mosler returned to the United States and settled in New York City. He continued to paint and exhibit, though the artistic landscape was beginning to shift. While his academic style remained popular with many patrons, newer movements like Impressionism (brought to America by artists like Mary Cassatt and Childe Hassam) and the emerging Ashcan School (with artists like Robert Henri and John Sloan focusing on gritty urban realism) were gaining prominence.

Despite these changing tastes, Mosler maintained a successful career. He was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design in New York in 1895, a significant recognition from his American peers. He continued to paint genre scenes, often drawing on his European sketches and experiences, but also turned to American subjects and landscapes. He also taught, holding a position as an instructor at the City College of New York.

His later works sometimes reflected a slightly looser brushwork, perhaps a subtle acknowledgment of prevailing trends, but he largely remained true to the detailed, narrative style that had brought him fame. He continued to participate in major exhibitions and received accolades, including a gold medal at the St. Louis Exposition in 1904.

Henry Mosler passed away in New York City on April 21, 1920, at the age of 78. He left behind a significant body of work that captured the life and sentiments of his era.

Legacy and Recognition

Henry Mosler's legacy is that of a highly skilled and successful academic painter who achieved international renown. He was one of the first American artists to gain significant recognition in the Paris Salon and to have his work purchased by the French government, paving the way for other American artists in Europe. His paintings of Breton peasant life remain iconic examples of 19th-century genre painting, valued for their technical mastery and their depiction of a vanishing way of life.

While his style might have been eclipsed by modernism in the early 20th century, there has been a renewed appreciation for 19th-century academic art in recent decades. Mosler's work is now seen as an important contribution to both American and European art of the period. His paintings are held in the collections of numerous museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., the Cincinnati Art Museum, and museums in France.

Exhibitions of his work, such as the 2022 show "Henry Mosler Behind the Scenes: In Celebration of the Jewish Cincinnati Bicentennial" at the Cincinnati Art Museum, continue to explore his artistic journey and his place within the broader context of 19th-century art and culture. His life story, from immigrant child to internationally acclaimed artist, reflects the opportunities and challenges of his time, and his art provides a rich visual record of the people and places that captured his imagination. He stands as a testament to the enduring power of narrative art and the transatlantic cultural currents that shaped the art world of the Gilded Age. His dedication to his craft and his ability to connect with audiences through universal human themes ensure his continued relevance in the study of art history.