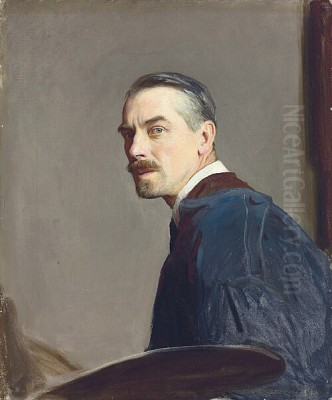

George Spencer Watson stands as a significant figure in British art during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in London in 1869 and passing away in 1934, Watson carved a distinct niche for himself primarily as a portrait artist. His work is often associated with the later phase of the Romantic movement in Britain, yet it possesses a unique character, frequently infused with stylistic elements reminiscent of the Italian Renaissance. He navigated an era of artistic transition, maintaining a commitment to representational elegance while contemporary movements were challenging traditional aesthetics.

Watson's journey as an artist was marked by academic recognition and a consistent dedication to his craft. His portraits, particularly those of women, are noted for conveying a sense of independence and quiet competence, moving beyond mere likeness to capture personality. His legacy is preserved not only through his canvases, many of which reside in public collections, but also through the story of his life and his place within the vibrant artistic milieu of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

George Spencer Watson was born in London on March 8, 1869. From an early age, he demonstrated a strong inclination towards the arts, an interest that was reportedly encouraged by his family. This foundational support set the stage for his formal artistic education. His commitment led him to the prestigious Royal Academy Schools, which he entered in 1889. The RA Schools were, at this time, the epicentre of establishment art training in Britain, presided over by influential figures whose impact shaped the institution's ethos.

Watson quickly distinguished himself during his studies. His talent was recognized through several accolades awarded by the Royal Academy itself. He received the RA Silver Medal in both 1889, the year he enrolled, and again in 1891. This early success was further solidified in 1892 when he won the Landseer Scholarship. These awards not only provided financial support but also marked him as a promising young artist within the competitive environment of the Academy, an institution then still heavily influenced by the legacies of figures like Frederic, Lord Leighton and Sir John Everett Millais.

Development of an Artistic Style

Watson's artistic voice matured into a distinctive blend of influences. Primarily identified with Late Romanticism, his work carries an emotional depth and sensitivity characteristic of the movement. However, he often integrated elements drawn from the Italian Renaissance, particularly in the composition, the graceful rendering of figures, and sometimes in the decorative details or the overall atmosphere of tranquil dignity. This fusion resulted in a style that was both contemporary in its sentiment and rooted in historical artistic traditions.

His technical skill was considerable. Watson was known for his delicate and refined brushwork, a soft yet deliberate application of colour, and a masterful handling of light and shadow to model form and create mood. His palette often favoured harmonious tones, contributing to the serene and sometimes idealized quality of his portraits. While portraiture formed the core of his output, he did not confine himself entirely to this genre, occasionally producing landscapes and nude studies, such as the work titled Us Riding, which explored different themes and compositional challenges.

The subjects of his portraits, especially his female sitters, are often depicted with a notable sense of presence and individuality. Rather than presenting purely passive or decorative figures, Watson frequently imbued his subjects with an air of thoughtful independence and capability, reflecting perhaps the changing roles of women in society during his lifetime. His style aimed for an elegance that felt inherent rather than imposed, capturing personality with subtlety and grace.

Professional Career and Recognition

Watson's talent, honed at the Royal Academy Schools, paved the way for a successful professional career integrated within the established British art institutions. His consistent exhibition record, starting with his first showing at the Royal Academy in 1891, built his reputation steadily. His skill, particularly in portraiture, led to his election to several prestigious art societies, signifying the respect he commanded among his peers.

In 1900, he became a member of the Royal Institute of Oil Painters (ROI), an organization dedicated to promoting the medium of oil painting. Four years later, in 1904, he was elected to the Royal Society of Portrait Painters (RP), a group specifically focused on the art of portraiture, placing him alongside the leading practitioners of the genre in Britain. His connection with the Royal Academy, the cornerstone of his education, continued throughout his career.

He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1923, a significant step towards full membership. The culmination of his institutional recognition came in 1932 when he was elected a full Royal Academician (RA). Membership in the RA was, and remains, one of the highest honours for an artist in Britain, confirming his status within the art establishment. He worked alongside and exhibited with many prominent contemporaries within these institutions, including the internationally renowned portraitist John Singer Sargent, the dynamic Sir William Orpen, and fellow RA portrait specialist Solomon J. Solomon.

Key Works and Themes

Several paintings stand out as representative of George Spencer Watson's oeuvre, showcasing his characteristic style and thematic interests. A Lady in Black, painted in 1922, is perhaps one of his most recognized works, notably held in the collection of Tate Britain in London. This portrait exemplifies his ability to combine elegance with psychological depth. The subject's direct gaze and poised demeanor, rendered against a simple background, highlight Watson's focus on capturing the sitter's personality through subtle expression and posture, all within a refined, almost austere, composition.

Another significant work is A Woman with a Leopard Skin Tippet from 1929. This painting demonstrates his skill in rendering textures – the softness of the fur against the sitter's skin – and his continued interest in portraying contemporary women with a sense of style and self-possession. The use of the leopard skin adds an element of fashionable exoticism, popular at the time, yet the focus remains on the individual.

His personal life also informed his art, as seen in works like Wife Walking in the Swiss Alps. This painting likely reflects his travels with his wife, Hilda, capturing a moment of leisure and connection with nature. It showcases his ability to handle landscape elements and integrate figures naturally within their environment, moving beyond formal studio portraiture. The work Us Riding indicates his engagement with other subjects, possibly equestrian or sporting themes, demonstrating a broader range of interests, though portraiture remained his primary focus. These works collectively illustrate his technical finesse, his interest in capturing character, and his blend of traditional elegance with a modern sensibility.

Personal Life and Influences

George Spencer Watson's personal life was closely intertwined with the arts. In 1909, he married Hilda Mary Gardiner, who was herself involved in the creative world as a dancer and mime artist. This union created a household steeped in artistic pursuits. Their shared life and travels, such as trips to the Swiss Alps, provided inspiration for some of his paintings, adding a personal dimension to his artistic output.

The couple had one daughter, Mary Spencer Watson (1913-2006), who followed in her parents' artistic footsteps, becoming a notable sculptor in her own right. Growing up in such an environment undoubtedly shaped Mary's career path, and the family represented a small nexus of creative activity. George Spencer Watson's role as both a practicing artist and the head of an artistic family highlights the supportive environment they cultivated.

Despite his professional successes and recognition, including his election as a Royal Academician late in his career, Watson's later life was not without its challenges. Sources suggest he faced periods of financial difficulty and declining health towards the end of his life. He passed away on April 7, 1934, shortly after receiving the highest honour from the Royal Academy. His life reflects the often-precarious reality of an artist's existence, even for those who achieve significant acclaim.

Context within British Art

George Spencer Watson worked during a period of significant change and diversification in British art. While he remained largely committed to the academic tradition fostered by the Royal Academy, his career unfolded against the backdrop of emerging modernist movements. His style, with its roots in Romanticism and Renaissance aesthetics, offered a continuation of established representational painting at a time when Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Vorticism were making inroads in Britain.

His contemporaries at the Royal Academy included artists who similarly balanced tradition with individual expression, such as Frank Dicksee, known for his narrative and sentimental paintings, and John William Waterhouse, whose work drew heavily on Pre-Raphaelite and mythological themes. Watson's refined portraiture can be seen as part of this lineage, prioritizing craftsmanship and emotional resonance. He stood somewhat apart from the bolder, more experimental styles of artists like Walter Sickert, a key figure in the Camden Town Group who focused on urban realism, or the expressive, bohemian portraits of Augustus John.

While John Singer Sargent's dazzling brushwork dominated society portraiture during much of Watson's career, Watson offered a quieter, perhaps more introspective approach. His work also contrasts with the classicism of RA stalwarts like Lawrence Alma-Tadema or the symbolic allegories of the older influential figure George Frederic Watts. Watson navigated this complex landscape by refining his own distinct blend of elegance, sensitivity, and technical polish, securing a respected place within the more traditional streams of British art, even as the avant-garde gained momentum. His connection to the RA placed him firmly within the establishment, upholding its values of skill and beauty.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

George Spencer Watson's legacy resides in his contribution to British portraiture and the Late Romantic tradition. His work represents a specific moment in art history, bridging the sensibilities of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras with the early 20th century. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his modernist contemporaries, his paintings possess an enduring quality derived from their technical mastery, psychological insight, and refined aesthetic.

His works continue to be held in significant public collections, most notably Tate Britain, ensuring their accessibility to future generations. The presence of his paintings in such institutions confirms his historical importance within the narrative of British art. Furthermore, his work retains value in the art market, as evidenced by auction results. For instance, a group of seven works fetching a notable sum (£85,800) in a 2024 auction indicates continued collector interest and appreciation for his skill and artistry.

Beyond his own canvases, Watson's influence extended through his family. His daughter, Mary Spencer Watson, carried the artistic mantle forward as a respected sculptor, ensuring the family name remained associated with creative practice in Britain for another generation. George Spencer Watson's art serves as a reminder of the depth and diversity of British painting during his time, representing a sophisticated strand of representational art that valued elegance, character, and a connection to tradition.

Conclusion

George Spencer Watson RA ROI RP remains a noteworthy figure in the annals of British art. As a prominent portrait painter active from the late Victorian era through to the early 1930s, he developed a distinctive style characterized by its blend of Late Romantic sensitivity and echoes of Renaissance grace. Educated and later honoured by the Royal Academy, he was an established figure whose career reflects both personal dedication and peer recognition within the institutional art world of his day.

His portraits, particularly of women, are celebrated for their elegance, technical skill, and insightful capture of personality. Works like A Lady in Black endure as testaments to his refined vision. While navigating a period of artistic upheaval, Watson maintained his commitment to a sophisticated form of representational art. His legacy is preserved through his paintings in public and private collections, the continuation of an artistic tradition through his daughter Mary, and his secure place as a skilled and sensitive chronicler of his time.