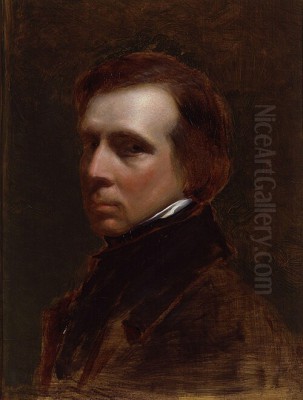

George Richmond stands as a significant figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century British art. Born in London on March 28, 1809, and passing away there on March 19, 1896, his long life spanned a period of immense social, industrial, and artistic change. While primarily celebrated today for his prolific and highly successful career as a portrait painter, capturing the likenesses of Victorian Britain's elite, his artistic journey began under the profound influence of one of England's most unique and visionary artists, William Blake. This early association shaped his initial output and left an indelible mark, even as he later adapted his style to meet the demands of a thriving portrait market. His story is one of artistic evolution, navigating the currents of influence, patronage, and personal conviction.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

George Richmond was born into an artistic household. His father, Thomas Richmond (1771–1837), was a respected painter of miniature portraits, ensuring that young George was immersed in the world of art from his earliest years. This familial connection provided both inspiration and a practical understanding of the artistic profession. Recognizing his son's burgeoning talent, Thomas Richmond encouraged his artistic pursuits.

Showing remarkable promise, George entered the prestigious Royal Academy Schools at the young age of fourteen, in 1824. This institution was the cornerstone of formal art education in Britain, founded by figures like Sir Joshua Reynolds. Here, Richmond would have received rigorous training in drawing, anatomy, and perspective, studying from antique casts and life models. During his time at the Schools, he also became a pupil of Joseph Severn (1793–1879), a painter best known today for his close friendship with the poet John Keats, whom he accompanied to Rome and nursed during his final illness. Severn's guidance would have provided Richmond with practical skills and insights into the contemporary art scene.

Richmond quickly distinguished himself. He began exhibiting at the Royal Academy's annual exhibition as early as 1825, signaling his arrival as a professional artist. His early works, however, were soon to be shaped by a far more potent and unconventional influence than that found within the Academy's hallowed halls.

The Ancients and the Shadow of Blake

Perhaps the most formative experience of Richmond's youth was his encounter and subsequent deep friendship with the poet, painter, and printmaker William Blake (1757–1827). Richmond met Blake around 1825, likely through John Linnell (1792–1882), another artist who became a crucial patron and friend to Blake in his later years. Richmond was immediately captivated by Blake's visionary genius, his spiritual intensity, and his rejection of the materialism and artistic conventions of the age.

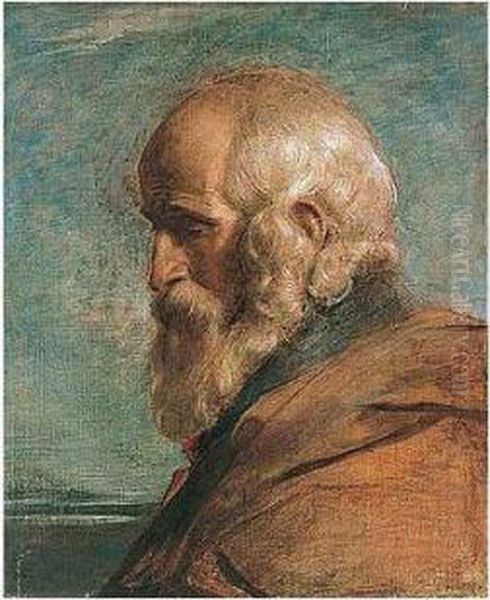

Richmond became a central figure in a group of young artists who gathered around the aging Blake, revering him as a spiritual and artistic guide. This group became known as "The Ancients." Its core members, besides Richmond, included Samuel Palmer (1805–1881), Edward Calvert (1799–1883), Francis Oliver Finch (1802–1862), and Frederick Tatham (1805-1878), who later became Richmond's brother-in-law. They were united by their admiration for Blake, a shared love for pastoral landscapes imbued with spiritual meaning, and an appreciation for early Renaissance and Northern European art, particularly the works of Albrecht Dürer and Lucas van Leyden.

The group often met at Samuel Palmer's rented cottage in the village of Shoreham, Kent, which they idealized as a rural paradise, a "Valley of Vision." Here, they sought to create art that was intense, spiritual, and deeply felt, drawing inspiration from the Bible, Milton, and the natural world perceived through a mystical lens. They experimented with techniques, including tempera painting and intricate engraving, seeking to emulate the perceived purity and intensity of earlier art forms.

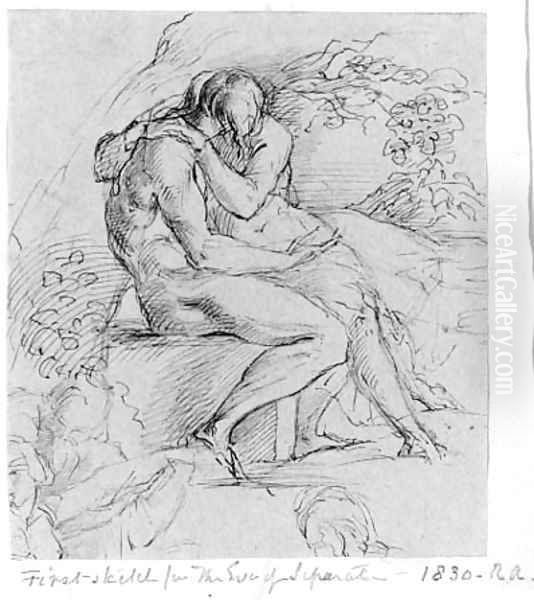

Richmond's work from this period (roughly 1825-1830) is markedly different from his later portraiture. It is characterized by a linear intensity, dramatic compositions, and a fervent religious or pastoral subject matter, clearly reflecting Blake's influence. Notable examples include the small but powerful tempera painting Abel the Shepherd (c. 1825, Tate Britain) and the engraving The Shepherd (1827). Another significant work from this time is Christ and the Woman of Samaria (1828, Tate Britain), which showcases the detailed, linear style and spiritual earnestness typical of The Ancients. Richmond was present at Blake's death in 1827 and, according to accounts, helped close the visionary's eyes, a poignant testament to their close bond. He also created a moving deathbed sketch of Blake.

The Turn Towards Portraiture

The intense, visionary style of The Ancients, while deeply fulfilling for its practitioners, found little favour with the broader art market or the established institutions like the Royal Academy. As Richmond matured and faced the practicalities of earning a living and supporting a family, the need for a more commercially viable artistic path became apparent. In 1831, he married Julia Tatham (1811–1881), the sister of fellow Ancient Frederick Tatham. This union brought personal happiness but also increased financial responsibilities.

Around this time, Richmond began to shift his focus towards portraiture. This was a logical step; his father was a miniaturist, and portraiture was a consistently lucrative genre in Britain, catering to the aristocracy, the burgeoning middle class, and prominent public figures. While this shift marked a departure from the overtly Blakean style of his youth, it did not represent a complete abandonment of his artistic principles. He brought to portraiture the meticulous draughtsmanship and sensitivity honed during his early years.

His transition was gradual but decisive. He initially specialized in watercolour portraits, often on a relatively small scale, which retained a certain intimacy and delicacy. These works quickly gained popularity, admired for their accurate likenesses, refined execution, and elegant presentation. He possessed a keen ability to capture not just the physical features but also a sense of the sitter's character and social standing.

A Premier Victorian Portraitist

Throughout the 1830s, 1840s, and beyond, George Richmond established himself as one of the most sought-after portrait painters in Victorian Britain. His success was built on his technical skill, his reliability, and his ability to produce flattering yet truthful likenesses that satisfied the expectations of his clientele. He moved comfortably within the upper echelons of society, and his studio became a destination for the great and the good.

His list of sitters reads like a 'Who's Who' of the Victorian era. He painted politicians, churchmen, writers, scientists, artists, members of the aristocracy, and royalty. Among his most famous subjects were:

William Wilberforce: The anti-slavery campaigner (Richmond painted him shortly before his death).

John Henry Newman: The influential theologian and later Cardinal.

William Ewart Gladstone: Four-time Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

Benjamin Disraeli: Gladstone's great political rival, also Prime Minister.

Thomas Babington Macaulay: Historian, essayist, and politician.

John Keble: Leading figure in the Oxford Movement.

Charlotte Brontë: Author of Jane Eyre. Richmond's chalk drawing (1850, National Portrait Gallery, London) is one of the few authenticated likenesses of the novelist.

Elizabeth Gaskell: Author of Cranford and North and South.

John Ruskin: The pre-eminent art critic, writer, and social thinker, whom Richmond met during his travels.

Charles Darwin: The naturalist whose theory of evolution revolutionized science. Richmond's watercolour portrait (c. 1839, Cambridge University) captures Darwin as a young man.

Michael Faraday: The pioneering scientist in electromagnetism.

Florence Nightingale: The founder of modern nursing.

Numerous bishops, archbishops (including Archbishop Tait), dukes, earls, and society figures.

His style evolved over his long career. While his early portraits were often in watercolour or chalk, he increasingly worked in oils, particularly for larger, more formal commissions. His oil portraits maintained the elegance and refinement of his earlier work but often possessed a greater sense of gravity and presence, suitable for public figures. Works like his portrait of Samuel Rogers (poet and patron of the arts) or Sir Robert Harry Inglis demonstrate his mature oil technique. He skillfully balanced detailed rendering of features and attire with a broader handling of background elements, ensuring the focus remained firmly on the sitter.

Richmond's success stemmed not just from technical prowess but also from his understanding of the social function of portraiture in the Victorian age. His portraits conveyed status, intellect, piety, and respectability – qualities highly valued by his clientele. They were fashionable yet dignified, avoiding excessive flamboyance while still capturing a sense of individual personality. He was compared favourably with contemporaries like Sir Francis Grant (1803–1878), another highly successful society portraitist who became President of the Royal Academy. While perhaps lacking the dazzling brushwork of a Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830) from the preceding generation, Richmond offered a sensitivity and psychological insight that resonated with Victorian tastes.

Technique and Versatility

While renowned for portraiture, Richmond's artistic practice encompassed other skills. His early training and association with The Ancients involved printmaking, and he produced several accomplished engravings, such as The Shepherd. His draughtsmanship remained fundamental throughout his career, evident in the numerous preparatory sketches and finished drawings he produced, particularly the sensitive chalk portraits like that of Charlotte Brontë.

His mastery of watercolour was exceptional. He handled the medium with delicacy and precision, achieving subtle gradations of tone and capturing textures effectively. This was particularly suited to the intimate scale of many of his earlier portraits. When working in oils, he employed a more traditional academic technique, building up layers of paint to achieve depth and luminosity, paying close attention to the rendering of fabrics and flesh tones.

Beyond painting and drawing, Richmond also engaged in other artistic activities. He is known to have undertaken some work in sculpture and was involved in art restoration. This breadth of activity reflects a deep engagement with the materials and processes of art-making. His interest in the Old Masters, particularly the Italian Renaissance artists like Michelangelo (evidenced by his drawing from a cast of David's arm), informed his understanding of form and composition throughout his life.

The Royal Academy and Professional Standing

George Richmond's career was closely intertwined with the Royal Academy of Arts. Having entered its schools as a boy and begun exhibiting there in 1825, he remained actively involved throughout his professional life. His growing reputation as a portraitist led to his election as an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1857. Full membership as a Royal Academician (RA) followed in 1866, cementing his position within the British art establishment.

He was a regular contributor to the Academy's annual Summer Exhibition, the most important showcase for contemporary art in Britain. His portraits were often prominently displayed, attracting critical attention and further commissions. He also served on various committees within the Academy, including the Academic Committee in 1873, contributing to its governance and educational mission.

Interestingly, despite his high standing, Richmond was twice nominated for the position of Keeper of the Royal Academy – a significant role responsible for the RA Schools – but either declined or was unsuccessful in securing the post. This might suggest a preference for focusing on his own lucrative portrait practice rather than taking on demanding administrative duties. His relationship with the Academy was thus one of consistent participation and recognition, culminating in the highest honour of full membership, even as he maintained a degree of independence. His success provided a stark contrast to the path taken by his early mentor, William Blake, who remained largely outside the academic mainstream.

Travels, Family, and Later Life

Like many artists of his time, Richmond valued travel, particularly to Italy, as a means of studying the Old Masters and broadening his artistic horizons. He made a significant trip to Italy in 1837-1839. During this time, he spent periods in Rome and Florence, sketching antiquities, studying Renaissance masterpieces, and interacting with other artists and intellectuals. It was during this trip that he met the young John Ruskin, forging a lasting friendship with the influential critic. These travels undoubtedly enriched his understanding of art history and technique, subtly informing his subsequent work.

Richmond's family life was also central to his identity. His marriage to Julia Tatham was a long and apparently happy one, producing ten children (though the initial provided text mentioned five, historical records often confirm ten). Several of his children inherited artistic talents. Most notably, his son Sir William Blake Richmond (1842–1921) became a highly successful painter and designer in his own right, known for his portraits, mythological subjects, and the extensive mosaic decorations he designed for St Paul's Cathedral – a project that echoed the grand ambitions perhaps latent in his father's early Blakean phase. The naming of his son explicitly acknowledged the enduring respect George Richmond held for his early mentor. Another family connection linked the Richmonds to the literary world: his daughter Julia married Alfred Darcy Dickens, son of the novelist Charles Dickens.

In his later years, Richmond continued to paint, though perhaps with less intensity than in his prime. He remained a respected figure in the London art world, embodying the success and stability of the Victorian academic tradition. He had successfully navigated the transition from a youthful, spiritually intense style influenced by Blake and The Ancients to become a leading portraitist, adapting his art to the tastes and demands of his time without entirely sacrificing artistic integrity. His biographer, Raymond Lister, acknowledged the high quality of his early, Blake-influenced work but ultimately concluded that Richmond's greatest achievement lay in his portraiture.

He died in his London home at 20 York Street, Portman Square, just shy of his 87th birthday, leaving behind a vast body of work and a significant legacy as a chronicler of Victorian society. His portraits offer an invaluable visual record of the prominent figures who shaped the era, captured with skill, elegance, and psychological insight.

Legacy and Context

George Richmond's legacy is twofold. He is remembered as a key member of The Ancients, the group of young disciples who gathered around William Blake, preserving and transmitting something of Blake's unique spirit through their own early works. This phase, though relatively short, produced art of remarkable intensity and originality, representing a fascinating, mystical counterpoint to the prevailing trends of the time. Artists like Samuel Palmer are perhaps more celebrated for their work from this period, but Richmond's contribution was significant.

However, the bulk of his career and his contemporary fame rested on his achievements as a portrait painter. In this role, he succeeded Sir Thomas Lawrence and rivaled Sir Francis Grant and George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) as one of the leading practitioners of the genre in Victorian Britain. While the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – including John Everett Millais (1829–1896), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882), and William Holman Hunt (1827–1910) – challenged academic conventions with their detailed realism and medieval themes, Richmond represented the continuity of a more traditional, elegant style of portraiture that remained highly popular with patrons. His work sits alongside that of other successful academicians like Frederic Leighton (1830–1896), President of the Royal Academy after Grant.

Richmond's career demonstrates the complex interplay between personal artistic vision, external influences (like Blake), academic training, and the demands of the art market. He successfully adapted his skills to build a prosperous career, becoming the favoured portraitist of the Victorian establishment. While his early, visionary works hold particular interest for their connection to Blake and The Ancients, his extensive oeuvre of portraits provides an enduring and insightful gallery of the faces that defined an age. His meticulous technique, combined with a sensitivity to character, ensures his place as a significant figure in the history of British art.