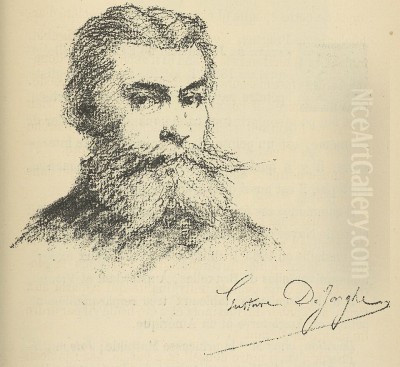

Gustave Léonard de Jonghe stands as a significant figure in 19th-century Belgian art. Born in Courtrai, Belgium, in 1829, he became renowned as a Flemish painter celebrated for his sophisticated portraits of women and meticulously rendered interior scenes. His work captured the essence of upper-class life, particularly in Paris, where he spent a considerable part of his successful career. De Jonghe passed away in 1893, leaving behind a legacy of elegance and refined realism that continues to be appreciated.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

De Jonghe's artistic journey began under the influence of his father, Jan Baptiste de Jonghe, himself a noted landscape painter. This familial connection to the art world undoubtedly nurtured young Gustave's talent. Seeking formal training, he enrolled at the prestigious Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. This academic grounding provided him with the technical skills necessary to embark on his own artistic path, honing his draftsmanship and understanding of composition and color. His early years in Brussels were formative, establishing the foundation for his later success. He began exhibiting his works at the Brussels Salon as early as 1848.

Success in the Parisian Art World

Seeking broader opportunities and exposure, Gustave de Jonghe made the pivotal decision to move to Paris, the undisputed center of the European art world in the mid-19th century. By the 1850s, he began exhibiting his paintings at the highly influential Paris Salon. It was here that his career truly flourished. He quickly gained recognition for his particular specialty: portraying elegant women, often members of the burgeoning bourgeoisie and aristocracy, within opulent domestic settings. His ability to capture both the likeness of his sitters and the luxurious details of their surroundings made him a sought-after artist in Parisian society.

Artistic Style: Realism and Refinement

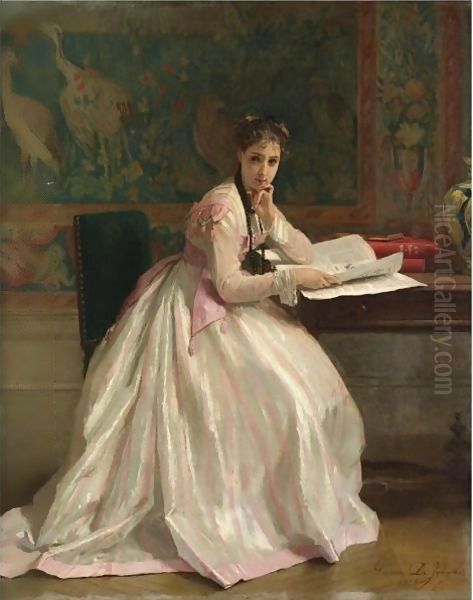

De Jonghe's artistic style is firmly rooted in Realism, yet it possesses a distinct elegance and often incorporates subtle Romantic sensibilities. He was a master technician, known for his delicate and precise brushwork, allowing him to render textures like silk, velvet, and lace with remarkable fidelity. His color palettes were typically harmonious and rich, contributing to the overall sense of luxury and calm that pervades his work. He paid meticulous attention to detail, not just in the figures themselves but also in the furniture, decorative objects, and architectural elements of the interiors he depicted.

His approach was characteristic of the popular Salon painters of the era, focusing on polished finishes and relatable, albeit idealized, subject matter. Unlike the more gritty Realism of artists like Gustave Courbet, de Jonghe's work focused on the refined aspects of contemporary life. He skillfully used light and shadow not just for modeling forms but also for creating mood and atmosphere, often bathing his scenes in a soft, inviting light that enhanced their intimacy and charm.

The primary theme throughout de Jonghe's oeuvre is the depiction of contemporary femininity, particularly within the context of upper-middle-class domesticity. His paintings often feature solitary women engaged in quiet activities – reading, contemplating, tending to children, or simply presenting themselves within their well-appointed homes. These scenes offer glimpses into the private lives and social roles of women during this period, capturing details of fashion, interior design, and social etiquette.

While his paintings celebrate elegance and material comfort, they also possess a psychological depth. De Jonghe was adept at conveying subtle emotions and moods through the posture, expression, and gestures of his figures. His works were praised by critics for their "sincerity" and "perfect taste," notably avoiding the sentimentality or overt narrative drama found in some other genre paintings of the time. He managed to imbue his scenes with a sense of quiet dignity and introspection.

Representative Works

Several key works exemplify Gustave de Jonghe's style and thematic concerns. Woman in Yellow (circa 1875), housed in the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, is a prime example of his portraiture. Though details of the specific scene rely on viewing the work, it undoubtedly showcases his skill in rendering fashionable attire – the yellow dress likely a focal point – and capturing the sitter's poise within an elegant setting, characteristic of his mature style.

The Japanese Fan (La admiradora de Japón), painted around 1865 and now in the collection of the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens in Florida, reflects the contemporary European fascination with Japanese art and objects, a trend known as Japonisme. The inclusion of a Japanese fan points to this cultural interest, adding an exotic touch to the otherwise familiar European interior. The painting likely portrays a fashionable woman interacting with or displaying this object, highlighting the intersection of Western society and Eastern aesthetics.

Awaiting the Suitor is another significant work that delves into narrative and emotion. The title itself suggests a story, likely depicting a young woman in a moment of anticipation or perhaps anxiety, waiting within her home. Such a painting would allow de Jonghe to explore themes of courtship, social expectations, and private emotion, all framed within his signature detailed interior setting.

The theme of family and domesticity is explored in works like Mother With Her Young Daughter. These paintings often portray tender moments between parent and child, emphasizing maternal affection and the comforts of family life within an affluent environment. They showcase de Jonghe's ability to capture intimate relationships and the innocence of childhood, rendered with his typical refinement and attention to detail in clothing and surroundings.

A Moment of Distraction highlights de Jonghe's skill in capturing quiet, introspective moments. Often depicting a woman pausing from an activity like reading, these works focus on subtle shifts in attention and mood. They demonstrate his mastery of light, color, and composition to create a harmonious and contemplative atmosphere, drawing the viewer into the subject's private world.

Beyond these specific examples, de Jonghe exhibited numerous other works that cemented his reputation, including paintings titled Le Baiser (The Kiss), Le Modèle (The Model), and Belgian, shown at the Paris Salon. Each contributed to his standing as a prominent painter of modern life and feminine grace. His consistent output and presence at major exhibitions ensured his visibility and success.

Context and Contemporaries

Gustave Léonard de Jonghe operated within a vibrant and competitive art scene, primarily in Paris. His father, Jan Baptiste de Jonghe (1), provided his initial artistic grounding. In Paris, Gustave's work found parallels with that of fellow Belgian expatriate Alfred Stevens (2). Stevens also achieved great fame for his depictions of elegant women in luxurious interiors, sharing a similar focus on fashion, texture, and the nuances of modern life. While the provided sources indicate no direct evidence of collaboration, their stylistic affinities place them within the same successful vein of Salon Realism.

Another Belgian contemporary mentioned as having a similar style, active in Paris, was Charles Baugniet (3), known for his portraits and genre scenes depicting the upper classes. Like de Jonghe and Stevens, Baugniet catered to the tastes of the Parisian elite, contributing to the popularity of this genre. The success of these Belgian artists in Paris highlights a significant cross-cultural exchange during this period.

The Paris Salon, where de Jonghe frequently exhibited, was the dominant art institution of the time. It showcased a wide range of styles, but academic and Realist painters often enjoyed significant success. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme (4) and William-Adolphe Bouguereau (5) were major figures, known for their highly polished techniques and popular subject matter, representing the established academic tradition against which newer movements would react.

While de Jonghe practiced a refined form of Realism, Paris was also a crucible for emerging styles. The Impressionist movement was taking shape during the latter part of his active career. Figures like Edgar Degas (6), whose work Ballet Room was noted in the source material, shared an interest in depicting modern life and female subjects, albeit with a radically different technique emphasizing spontaneity and light effects. De Jonghe's polished style contrasts sharply with Impressionism but coexisted within the diverse Parisian art world.

Other artists active in Paris during or overlapping with de Jonghe's career included the Dutch painter Johannes Barthold Jongkind (7), considered a precursor to Impressionism, known for his atmospheric cityscapes and coastal scenes – a different focus from de Jonghe's interiors. The French painter Théodore Jung (8) captured panoramic views of the city, while the Dutch artist Roland Orlando Jongledor (9) also exhibited internationally, including in Paris. These artists represent the variety of work being produced and shown.

Influential figures like Gustave Courbet (10), the leading proponent of Realism, and Édouard Manet (11), who bridged Realism and Impressionism, were also key players whose work shaped the artistic debates of the time. Additionally, artists like James Tissot (12), though French, spent time in London and also specialized in painting scenes of fashionable society, sharing some thematic ground with de Jonghe. De Jonghe navigated this complex environment, carving out a successful niche with his particular brand of elegant Realism.

Later Life and Lasting Legacy

Gustave de Jonghe's prolific painting career came to an abrupt and tragic end. In 1882, he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage which resulted in blindness. This devastating event forced him to cease painting entirely, cutting short his artistic production while he was still highly regarded. Despite this misfortune, the body of work he had already created was substantial and had secured his reputation.

He lived for another eleven years after losing his sight, passing away in 1893 at the age of 64. In his later years, the art community recognized his contributions and plight; the source material mentions support through a charity auction, indicating the esteem in which he was held.

Today, Gustave Léonard de Jonghe is remembered as a significant Belgian painter of the 19th century and a master of genre painting and portraiture. His works are valued for their technical excellence, their charming depiction of period elegance, and the insightful glimpses they offer into the lives of women in high society. His paintings serve as important documents of the fashion, interiors, and social atmosphere of his time.

His legacy endures through the works held in various public and private collections. Key pieces reside in institutions such as the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute and the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens. The Art Renewal Center, dedicated to reviving appreciation for traditional painting, also lists numerous works by him, indicating continued interest in his skillful artistry. De Jonghe remains an important figure for understanding the nuances of 19th-century Realism and the popular tastes of the Salon era.

Conclusion

Gustave Léonard de Jonghe carved a distinct and successful path in the 19th-century art world. From his early training in Brussels to his celebrated career in Paris, he developed a signature style characterized by meticulous Realism, refined elegance, and a focus on the lives of contemporary women. His paintings, admired for their technical skill, harmonious beauty, and subtle emotional depth, captured the spirit of Parisian high society. Though his career was tragically shortened by blindness, de Jonghe left behind a significant body of work that continues to enchant viewers and provides valuable insight into the aesthetics and social fabric of his era. He remains a noteworthy representative of Belgian art and the sophisticated tastes of the Paris Salon.