George William Mote stands as a fascinating figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art. Born in 1832 and passing away in 1909, he dedicated his artistic life to capturing the nuanced beauty and quiet dignity of the English and Welsh countryside. A largely self-taught painter, Mote developed a distinctive style characterized by detailed observation and a deep empathy for rural life, positioning him as an inheritor of the great English landscape tradition while forging his own unique path. His journey from gardener to recognized artist, his specific focus on pastoral themes, and his eventual, though sometimes obscured, recognition within art history make him a subject worthy of closer examination.

From Garden to Gallery: An Unconventional Path

George William Mote's origins were humble, setting him apart from many contemporaries who benefited from formal academic training. He was born in Rowley Green, near Barnet, Hertfordshire, in 1832. His early professional life was not spent in studios or academies, but outdoors, working as a gardener. This hands-on experience with the land, observing the cycles of nature, the textures of foliage, and the play of light across the fields, undoubtedly provided him with an intimate knowledge and deep appreciation that would later infuse his artwork.

Driven by an innate artistic inclination, Mote embarked on the challenging path of self-education in painting. This transition from horticulture to fine art speaks volumes about his determination and passion. By 1857, his efforts bore fruit when he achieved his first significant public recognition: exhibiting works at the prestigious Royal Academy in London. Among these early submissions were paintings titled Greenwich Park and Horsham Harbour, indicating his initial focus on specific, identifiable locations within England.

The Development of a Distinctive Style

Mote's artistic voice matured into a style noted for its directness and sincerity. He became particularly known for his depictions of the landscapes and rural activities of England and Wales. His approach avoided overt dramatization, favouring instead a careful, almost meticulous rendering of natural detail. His background as a gardener likely contributed to his exceptional ability to depict trees, flowers, and foliage with botanical accuracy and sensitivity.

The influence of the great English landscape painter John Constable (1776-1837) is evident in Mote's work. Like Constable, Mote was deeply interested in capturing the authentic atmosphere of the countryside, the effects of light and weather, and the simple poetry of rural existence. He sought to convey the essence and inner feeling of nature, emphasizing its purity and unadorned beauty rather than imposing a contrived picturesque formula. His paintings often possess a quiet, contemplative quality, inviting the viewer to appreciate the subtle harmonies of the natural world.

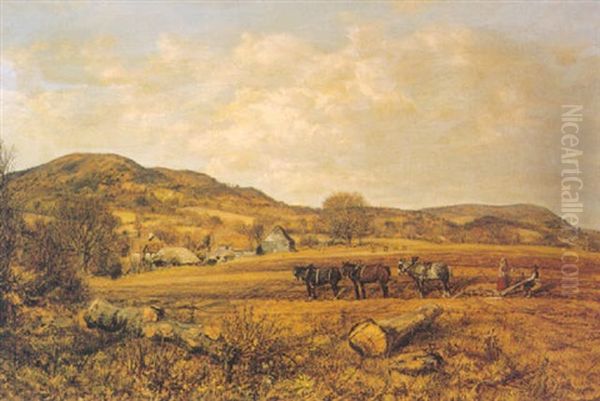

Mote's style can be seen as a blend of Realism and Romanticism. The realistic impulse is clear in his detailed observation and faithful representation of scenes – the textures of hay, the specific forms of trees, the accurate depiction of agricultural tools and practices. Yet, his work is imbued with a romantic sensibility, a deep feeling for the beauty and tranquility of the countryside, often presenting an idyllic vision that stood in contrast to the increasing industrialization of Victorian Britain. This combination resulted in works that felt both grounded and gently evocative.

Key Themes and Representative Works

Mote's oeuvre revolved around the rhythms of rural life and the enduring beauty of the British landscape. He frequently depicted scenes of agricultural labour, such as haymaking and harvesting, capturing moments of communal effort and connection to the land. His figures are typically integrated naturally into the landscape, part of its fabric rather than dominant elements. Seasonal changes also provided rich subject matter, allowing him to explore different palettes and atmospheric effects.

Several specific works help illustrate his artistic concerns. His early Royal Academy exhibits, Greenwich Park and Horsham Harbour (1857), show his engagement with specific locales. Later works mentioned include The Reapers, a title suggesting a focus on harvest themes, similar perhaps to the work of French Realist Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), though likely rendered with a distinctly English sensibility. Partridge Shooting points to his depiction of country sports and leisure within the landscape.

A work titled The Heather suggests his interest in capturing specific types of vegetation and terrain, perhaps moorland scenes. An 1885 painting referred to as Hay Wain Landscape (or similar title, potentially Landscape with Hay Wain) inevitably invites comparison with Constable's masterpiece. While likely depicting a similar common rural subject rather than being a copy, it underscores Mote's engagement with the established iconography of English pastoral painting. These works collectively showcase his commitment to detailed representation, his love for the textures and light of the countryside, and his focus on traditional rural life.

Exhibitions, Patronage, and Recognition

Throughout his career, George William Mote continued to exhibit his work, though his participation in major London exhibitions like the Royal Academy appears to have been intermittent rather than continuous. This might reflect the challenges faced by a self-taught artist in navigating the competitive Victorian art world, or perhaps a personal preference for a quieter, more regionally focused career.

Despite this, Mote did attract significant support. One of his most important patrons was the renowned bibliophile and collector Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792-1872) of Middle Hill, Worcestershire. Phillipps's interest was substantial enough that he included eight of Mote's paintings in his privately published catalogue, Middle Hill Pictures. This patronage provided Mote not only with financial support but also with validation and exposure within influential circles. The collector James Fox is also noted as having owned several of Mote's paintings, indicating a broader base of appreciation.

Some sources mention Mote's participation in the Great Exhibition of 1851. However, given that his first known public exhibition was at the Royal Academy in 1857 and he was still developing his skills as a self-taught artist in the early 1850s, this claim requires careful consideration and verification. It's possible there is confusion with another artist or event. His documented exhibitions at the Royal Academy and his connection with patrons like Phillipps remain the most solid evidence of his contemporary recognition.

Mote in the Context of Victorian Art

To fully appreciate George William Mote's contribution, it's helpful to place him within the broader context of 19th-century British art. Landscape painting was a dominant and highly popular genre throughout the Victorian era, building on the legacy of giants like J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and John Constable. Mote clearly aligns with the Constable tradition, focusing on the native landscape rendered with fidelity and feeling.

He worked during a period when various artistic trends coexisted. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, including artists like John Everett Millais (1829-1896) and William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), emphasized intense detail and truth to nature, often with moral or literary themes. While Mote shared their commitment to detailed observation of the natural world, his work generally lacked the high-keyed colour and complex symbolism of the Pre-Raphaelites, retaining a more traditional landscape approach.

Mote's focus on idyllic rural scenes also resonates with the work of popular watercolourists like Myles Birket Foster (1825-1899) and Helen Allingham (1848-1926), who specialized in charming depictions of cottages, gardens, and village life. However, Mote primarily worked in oils and often tackled broader landscape views alongside these more intimate subjects. He can also be considered alongside successful contemporaries in oil landscape painting such as Benjamin Williams Leader (1831-1923) and George Vicat Cole (1833-1893), who also enjoyed considerable public acclaim for their depictions of the British countryside, though their styles differed in handling and sentiment.

Interestingly, Mote's career also overlapped with the rise of the Arts and Crafts Movement, spearheaded by figures like William Morris (1834-1896). Some sources suggest Mote advocated for artistic authenticity and the value of handicrafts, and even indicate an awareness of Japanese art principles, which were becoming increasingly influential in Britain during the later 19th century. While direct links need further research, this potential alignment with Arts and Crafts ideals – valuing honest workmanship, natural forms, and potentially simpler, non-academic approaches – offers another intriguing layer to understanding his artistic position.

Later Life, Misattributions, and Reassessment

In his later years, George William Mote reportedly moved to Ewhurst in Surrey (some sources mention "Ewherston," likely a misspelling or variant), a county known for its picturesque landscapes that attracted many artists. He continued to paint, presumably finding inspiration in his new surroundings and maintaining his focus on rural themes and the quiet observation of nature. This period likely represented a continuation of his established style, reflecting a lifelong dedication to his chosen subject matter.

A peculiar aspect of Mote's posthumous reputation involves misattribution and rediscovery. It has been noted that for a time, his work was sometimes overlooked or even misidentified. An anecdote recounts that one of his paintings was mistakenly attributed to Richard Redgrave (1804-1888), a prominent Victorian painter, designer, and art administrator known for his landscapes and genre scenes. This particular painting was later correctly identified and sold under Mote's name in 2020. Such instances highlight the complexities of artistic attribution and reputation, especially for artists who may not have consistently maintained a high profile in major metropolitan centres.

Furthermore, it's mentioned that Mote's work was, at some point, potentially undervalued, with some perhaps classifying him as a "primitive" or naive painter, possibly due to his self-taught background or his direct, unpretentious style. However, the 2020 sale under his own name, and ongoing interest from collectors and galleries, suggests a welcome reassessment. Art historians and the market are increasingly recognizing the quality, sincerity, and distinct charm of his work, appreciating his skilled rendering of the natural world and his authentic connection to the landscapes he depicted. This ongoing reappraisal helps to secure his rightful place within the narrative of British landscape painting.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

George William Mote occupies a specific and valuable niche in British art history. He was not a radical innovator who dramatically altered the course of landscape painting, nor did he achieve the towering fame of Constable or Turner. However, his contribution lies in his dedicated and skillful chronicling of the English and Welsh countryside during a period of significant social and environmental change. His work offers a sincere, detailed, and often poetic vision of rural life, rendered with a technique honed through personal observation and dedication rather than formal academic training.

His connection to the tradition of John Constable is clear, yet he developed his own recognizable style, characterized by its meticulous detail, quietude, and empathetic portrayal of nature and rural labour. He stands apart from the more dramatic or overtly sentimental trends of some Victorian art, offering a more grounded and understated perspective. His paintings serve as valuable documents of specific locations and agricultural practices, while also transcending mere topography to convey a genuine love for the land.

The story of his journey from gardener to exhibiting artist, the support he received from discerning patrons like Sir Thomas Phillipps, and the recent corrections of misattributions all contribute to a more complete understanding of his career. While perhaps overshadowed during periods by contemporaries like B.W. Leader or G.V. Cole, or stylistically distinct from movements like Pre-Raphaelitism or later Impressionist-influenced artists like Philip Wilson Steer (1860-1942), Mote's work endures.

In conclusion, George William Mote was a significant British landscape painter whose dedication to capturing the authentic spirit of the countryside resulted in a body of work characterized by skill, sincerity, and quiet beauty. His unique background and the subsequent rediscovery of his art add layers of interest to his story. He remains an important figure for those studying Victorian art, British landscape painting, and the enduring artistic fascination with the rural world, offering a distinct and valuable perspective honed through a life spent in close observation of nature.