George William Sotter stands as a distinguished figure in the annals of American art, particularly celebrated for his evocative nocturnes and masterful depictions of the Pennsylvania landscape. His ability to capture the ethereal qualities of light, whether the cold glow of moonlight on snow or the warm radiance emanating from a cottage window, cemented his reputation as a key member of the Pennsylvania Impressionist movement, also known as the New Hope School. Sotter's artistic journey, from a craftsman in stained glass to a painter of national renown, is a testament to his unique vision and technical prowess.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1879, George William Sotter's early environment was the industrial heartland of America. This setting, characterized by fiery furnaces and smoky skies, perhaps subtly informed his later fascination with dramatic light and atmospheric effects. His formal artistic training began in his hometown, but it was his matriculation at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia that proved formative. Founded in 1805, PAFA was, and remains, one of America's most prestigious art institutions, a crucible for many of the nation's finest talents.

At PAFA, Sotter had the privilege of studying under a cadre of influential artists. Among them was Thomas Anshutz, a respected figure painter and successor to Thomas Eakins, known for his rigorous approach to anatomy and composition. Another significant mentor was William Merritt Chase, a leading American Impressionist and a charismatic teacher who encouraged outdoor painting and a vibrant palette. Chase's influence was widespread, touching many artists who would go on to define American Impressionism. Sotter also benefited from the tutelage of Henry Keller, a Cleveland-based artist known for his watercolors and innovative color theories, who likely broadened Sotter's understanding of chromatic harmonies.

The Allure of Stained Glass

Before fully dedicating himself to easel painting, Sotter embarked on a successful career as a stained-glass artist. This early profession was not merely a stepping stone but a profound influence on his later painterly style. Working with colored glass inherently involves an understanding of how light transmits and refracts, how colors interact when illuminated, and how leading can define form and create rhythm. This deep, practical knowledge of luminosity and color saturation would become a hallmark of Sotter's paintings.

His skill in stained glass was considerable, leading to significant commissions. He designed and executed windows for numerous churches and public buildings, including notable work for the New Jersey State House. The discipline of translating designs into the intricate patterns of glass, cutting and assembling pieces to catch and transform light, endowed him with a unique sensitivity to the visual power of light itself. This experience differentiated him from many of his contemporaries and gave his canvases a distinctive glow, often described as an "inner light."

The Move to Bucks County and the New Hope School

A pivotal moment in Sotter's career came with the encouragement of Edward Redfield, another towering figure of Pennsylvania Impressionism, known for his vigorous, large-scale snowscapes. Redfield, who also taught at PAFA for a period, recognized Sotter's talent and urged him to move to the Bucks County area, which was rapidly becoming a haven for artists. In 1902, Sotter first established a studio near Redfield in Centre Bridge, and by 1919, he and his wife, the artist Alice Bennet Sotter, settled permanently in Holicong, Bucks County.

This region, with its rolling hills, meandering Delaware River, picturesque stone farmhouses, and distinct seasons, provided endless inspiration. Sotter became an integral part of the New Hope School, a group of artists drawn to the area's natural beauty and the camaraderie of a burgeoning art colony. This group, which included luminaries such as William L. Lathrop (often considered the "dean" of the New Hope painters), Daniel Garber, Robert Spencer, Charles Rosen, and R. Sloan Bredin, developed a distinctly American brand of Impressionism. While influenced by French Impressionism's emphasis on light, color, and plein air painting, the Pennsylvania Impressionists often favored more structured compositions and a robust, sometimes Tonalist-inflected, realism.

The Signature Style: Nocturnes and Luminous Skies

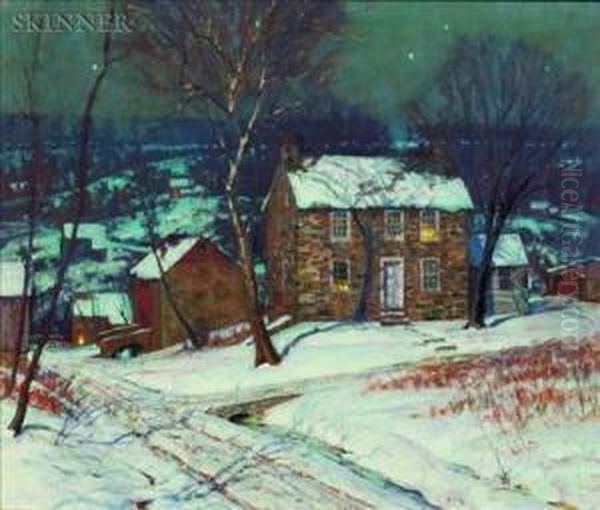

While Sotter painted a variety of subjects, including daytime landscapes and architectural studies, he is most celebrated for his nocturnes and his depictions of dramatic skies. His night scenes are not merely dark canvases but are imbued with a subtle, captivating light. He masterfully rendered the soft glow of moonlight on snow-covered fields, the twinkling of stars in a vast winter sky, or the warm, inviting light spilling from the windows of a solitary farmhouse. These works evoke a sense of tranquility, mystery, and sometimes a poignant nostalgia.

His training in stained glass is particularly evident in these nocturnes. The deep blues, violets, and indigos of the night sky often have a jewel-like quality, and the way light emanates from within the scene, as if the canvas itself were illuminated, recalls the effect of light passing through colored glass. Sotter had an uncanny ability to convey the chill of a winter night while simultaneously offering the comfort of a distant light, creating a powerful emotional resonance. His skies, even in daylight scenes, are rarely passive backdrops; they are dynamic compositions of cloud, color, and light, often dominating the canvas and setting the mood for the entire piece.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

Several paintings exemplify Sotter's unique artistic vision. Homestead at Night is a quintessential Sotter nocturne, showcasing a snow-covered landscape under a starlit sky, with the warm glow from a farmhouse window providing a focal point of human presence and warmth amidst the cold. The interplay between the cool blues of the snow and sky and the warm yellows and oranges of the window light is a hallmark of his technique.

Bucks County Nocturne is another iconic work, often celebrated for its atmospheric depth and the artist's sensitive handling of moonlight. Such paintings demonstrate his profound understanding of how light behaves in low-illumination conditions, capturing subtle gradations of tone and color that many other artists might miss. The success of works like this in the art market, with Bucks County Nocturne reportedly fetching significant sums at auction, underscores their enduring appeal.

Miner's Mills Grain Mill (sometimes referred to as The Mill, Miner's Mills) showcases his ability to find beauty in vernacular architecture and imbue it with a sense of timelessness. The golden light emanating from the mill's windows contrasts with the cool tones of the surrounding snow and evening sky, creating a scene that is both realistic and poetic. This work, like many others, highlights his skill in rendering the textures of stone, wood, and snow under varying light conditions.

Other significant pieces include Moonlight, Bucks Barn , which would undoubtedly feature his characteristic luminous moonlight and deep, resonant shadows, and Winter Nocturne, a title that encapsulates his most favored theme. These paintings are not just depictions of places but are evocations of mood and atmosphere, inviting contemplation and a quiet appreciation of nature's subtle dramas.

Contemporaries and Artistic Dialogue

Sotter did not create in a vacuum. He was an active participant in a vibrant artistic community. His relationship with Edward Redfield was crucial, not only for the encouragement to move to Bucks County but also as a fellow artist exploring similar themes, albeit often with a more rugged, impasto technique. Daniel Garber, another leading figure of the New Hope School, was known for his detailed, tapestry-like depictions of the Pennsylvania landscape, often bathed in a shimmering light, offering a different yet complementary vision to Sotter's.

Robert Spencer, with his focus on the mills and tenements of the Delaware River towns, brought a social realist dimension to the Pennsylvania Impressionist group, often depicting the lives of workers. Charles Rosen, initially an Impressionist, later explored more modernist tendencies, reflecting the evolving artistic currents of the early 20th century. R. Sloan Bredin was known for his more genteel, decorative figures in idyllic landscapes. William L. Lathrop, whose home at Phillips Mill became a central gathering place for artists, fostered a supportive environment for this diverse group.

Beyond the immediate New Hope circle, Sotter's education at PAFA connected him to a broader lineage. His teacher, William Merritt Chase, was a contemporary of other major American Impressionists like Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, and John Henry Twachtman, who were shaping a distinctly American response to the French movement. Thomas Anshutz, in turn, linked Sotter to the realist tradition of Thomas Eakins. Sotter also taught, serving as an Assistant Professor at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in Pittsburgh from 1910 to 1919, where he would have interacted with another generation of aspiring artists and faculty, potentially including figures associated with the burgeoning art scene in Western Pennsylvania. His colleagues and students there would have been exposed to his unique approach to light and landscape.

The artistic environment of the early 20th century was dynamic. While Sotter remained largely committed to his Impressionistic style, he was aware of other movements. The Armory Show of 1913, for instance, introduced European modernism to America on a grand scale, challenging traditional modes of representation. Artists like Arthur B. Carles and Hugh Henry Breckenridge, both with PAFA connections, were among those who embraced more modernist, abstracting tendencies. Sotter's steadfast dedication to his particular vision of landscape, rooted in keen observation and a profound sensitivity to light, provided a counterpoint to these more radical explorations.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Teaching

Sotter's work gained national recognition through numerous exhibitions. He regularly showed at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he received several awards, including a silver medal in 1923. His paintings were also exhibited at prestigious venues such as the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the National Academy of Design in New York, and the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh. A significant early honor was his inclusion in the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915, a major event that showcased American artistic achievement to an international audience. Sotter received a silver medal at this exposition, further solidifying his national reputation.

His role as an educator at the Carnegie Institute of Technology for nearly a decade was also an important facet of his career. In this capacity, he taught painting and design, influencing students with his technical knowledge and artistic philosophy. This period of teaching in Pittsburgh, before his permanent move to Holicong, demonstrates his commitment to fostering artistic talent and his connection to his native city's cultural life. The dual demands of a teaching career and an active painting practice were common for many artists of his era, providing financial stability and intellectual stimulation.

The Enduring Legacy of George William Sotter

George William Sotter passed away in 1953 in Holicong, Pennsylvania, the landscape he had so lovingly depicted for much of his career. His death marked the end of an era for the New Hope School, as many of its founding members were aging or had already passed. However, his artistic legacy endures. His paintings are held in the permanent collections of numerous museums, including the James A. Michener Art Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, which has a significant collection of Pennsylvania Impressionist works, as well as institutions like the Reading Public Museum and, historically, the Carnegie Institute.

Sotter's work continues to be highly sought after by collectors, and his auction prices reflect a sustained appreciation for his unique talent. The appeal of his paintings lies in their technical brilliance, their evocative power, and their ability to transport the viewer to a quieter, more contemplative world. He captured not just the appearance of the Pennsylvania landscape but its soul, particularly under the mystical cloak of night or the dramatic sweep of a cloud-filled sky.

In the broader context of American art, Sotter is recognized as one of the most distinctive voices within the Pennsylvania Impressionist movement. His specialization in nocturnes, informed by his stained-glass background, set him apart. While other American artists, such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler, had famously explored the nocturne form, Sotter brought a uniquely American sensibility to the genre, rooted in the specific character of the Bucks County landscape. He demonstrated that Impressionist principles could be adapted to capture the full range of nature's moods, from the brightest day to the deepest night. His contribution to American art lies in his masterful fusion of keen observation, technical skill, and a poetic sensibility, leaving behind a body of work that continues to enchant and inspire.