Robert Spencer stands as a significant, if sometimes melancholic, voice within the chorus of American Impressionism. Active during the early twentieth century, he carved a distinct niche for himself, particularly within the celebrated New Hope art colony in Pennsylvania. Unlike many of his contemporaries who focused on idyllic landscapes, Spencer was drawn to the everyday life of towns, the stoic beauty of mills and tenements, and the lives of the working class. His work, characterized by a subtle, often somber palette and a deeply felt emotional honesty, offers a poignant glimpse into the American scene of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Robert Coombs Spencer Jr. was born on December 1, 1879, in Harvard, Clay County, Nebraska. His father, a Swedenborgian clergyman, moved the family frequently during Spencer's youth, eventually settling in Yonkers, New York. This peripatetic childhood perhaps instilled in him a keen observational sense. Initially, Spencer pursued a path in medicine, but the call of art proved stronger. By 1899, he had made the decisive shift, enrolling at the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York City, where he studied for two years.

His artistic education continued at the New York School of Art (formerly the Chase School of Art) from 1903 to 1905. Here, he came under the tutelage of two towering figures in American art: William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri. Chase, a leading American Impressionist, would have imparted a mastery of painterly technique, an understanding of light, and the principles of Impressionism. Henri, on the other hand, was the charismatic leader of the Ashcan School, advocating for art that depicted the gritty realities of urban life. This dual influence was formative for Spencer, equipping him with Impressionist methods while instilling a focus on contemporary, everyday subject matter. Other students who would have been part of this vibrant New York art scene, or whose influence was felt, included figures like George Bellows, Edward Hopper, and Rockwell Kent, all of whom were, in their own ways, seeking to define a modern American art.

The Lure of New Hope

Around 1906, Spencer began visiting the burgeoning art colony in New Hope, Pennsylvania, situated along the scenic Delaware River. He was drawn by the area's picturesque mills, canals, and stone houses, as well as the community of artists congregating there. By 1909, he had made New Hope his permanent home. The New Hope art colony, often referred to as the Pennsylvania Impressionists or the New Hope School, was one of the most important centers for Impressionist landscape painting in America.

Key figures already established or emerging in New Hope included Edward Willis Redfield, known for his vigorous, large-scale snow scenes, and William Langson Lathrop, whose farm often served as a gathering place for artists and who was considered the "dean" of the colony. Spencer soon formed a close association with Daniel Garber, another prominent member of the group, whose style was characterized by a more decorative, high-key, and lyrical approach to landscape. For a time, Spencer even lived with Garber and his wife. Other notable artists associated with the New Hope School, whose paths Spencer would have crossed, included Charles Rosen, Walter Elmer Schofield (though Schofield spent much time in England), Rae Sloan Bredin, Morgan Colt, and George Sotter. While these artists shared an interest in Impressionist techniques and plein air painting, Spencer's focus remained distinct.

A Singular Artistic Vision: Style and Themes

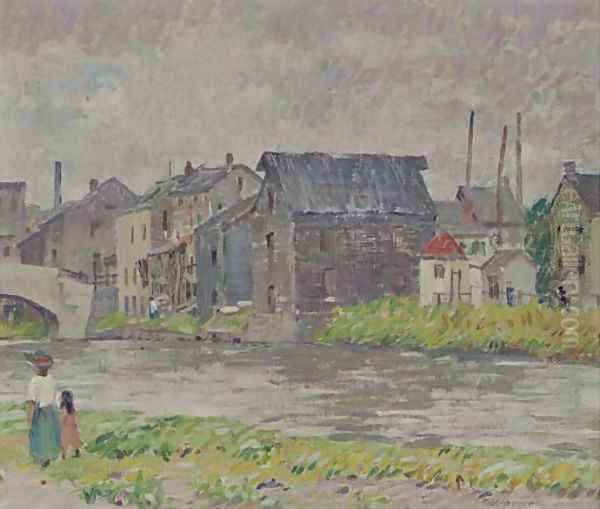

While firmly rooted in Impressionism, Robert Spencer’s style evolved into something uniquely his own. He employed the broken brushwork, attention to atmospheric light, and vibrant (though often muted) color characteristic of the movement. However, his palette often leaned towards more subtle, sometimes somber, grays, blues, and ochres, reflecting the character of his chosen subjects. His paintings possess a quiet poetry, a sense of lived reality, and a deep empathy for the scenes and people he depicted.

Spencer's primary subjects were the mills, factories, tenements, and working-class homes of New Hope and nearby towns like Lambertville, New Jersey. He was fascinated by the textures of old stone, the play of light on weathered wood, and the human element within these industrial or domestic landscapes. Unlike many Impressionists who sought out pristine nature, Spencer found beauty in the man-made environment, often depicting scenes of labor or the quiet dignity of everyday existence. His compositions frequently featured a high horizon line, giving a sense of enclosure or intimacy, and he often painted views of the town rather than panoramic vistas from it. This perspective created a feeling of being immersed in the community. His figures, though often small within the larger composition, are integral to the scene, suggesting narratives of daily life, struggle, and perseverance. This focus on the social landscape set him apart from many of his New Hope colleagues, aligning him more, in spirit, with the urban realism of Robert Henri and the Ashcan School, though his technique remained Impressionistic.

Masterworks and Recognition

Throughout his career, Robert Spencer produced a body of work that garnered significant acclaim. Several paintings stand out as particularly representative of his mature style and thematic concerns.

One of his most celebrated works is Repairing the Bridge (1914). This painting, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, depicts a group of workers engaged in the reconstruction of a bridge, likely in the New Hope area. The composition is dynamic, with the strong diagonals of the bridge structure contrasting with the more organic forms of the figures and landscape. The palette is rich yet controlled, capturing the light and atmosphere of a working day. This painting earned Spencer a gold medal at the prestigious Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915, a significant honor that solidified his national reputation.

Another important piece is On the Canal, New Hope (circa 1920s), which is housed in the Detroit Institute of Arts. This work exemplifies his ability to find beauty in the industrial infrastructure of the region. The tranquil waters of the canal reflect the surrounding buildings and sky, rendered with Spencer's characteristic sensitivity to light and color. The scene is imbued with a quiet, almost melancholic atmosphere, typical of his oeuvre.

The Village Lane (1919) and The Gray Bridge (circa 1925) are further examples of his engagement with the local scenery. These works showcase his skill in capturing the specific character of New Hope, with its stone houses, winding lanes, and the ever-present Delaware River and Canal. His paintings often evoke a sense of time and place, a feeling that these are not just picturesque views but lived-in environments with their own histories and stories.

Spencer exhibited widely throughout his career, including at the National Academy of Design, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago. His work was admired by critics and collectors alike. Duncan Phillips, the pioneering collector and founder of The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., was a significant admirer and patron, acquiring several of Spencer's paintings. Phillips saw in Spencer's work a uniquely American sensibility, one that captured the spirit of the nation's towns and working people.

The New Hope Group and Broader Connections

Spencer was an active participant in the New Hope art community. He was a member of "The New Hope Group," an informal association of artists that included Redfield, Garber, Schofield, Lathrop, Rosen, and Bredin. This group exhibited together, promoting the distinctive style of Pennsylvania Impressionism. While camaraderie existed, there was also a healthy sense of artistic individuality and, at times, friendly rivalry, which spurred creative development.

Beyond New Hope, Spencer's connections extended to the broader American art world. His training with Chase and Henri linked him to two of the most influential currents in American art at the turn of the century: Impressionism and the burgeoning realist movement. While he embraced Impressionist techniques, his subject matter often resonated with the Ashcan School's desire to portray "life as it is." Artists like John Sloan, George Luks, and Everett Shinn, all part of Henri's circle, were similarly engaged in depicting the urban experience, though often with a more overtly gritty or satirical edge than Spencer's more poetic interpretations of small-town industrial life.

The influence of earlier American landscape painters, such as those from the Hudson River School, can be seen as a backdrop to the American Impressionist movement, though the Impressionists broke sharply with their predecessors' detailed realism in favor of capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere. Furthermore, the impact of French Impressionists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley was, of course, foundational for American artists adopting the style, though American Impressionism often retained a greater sense of solidity and form. Spencer, like many of his American peers such as Childe Hassam or J. Alden Weir, adapted Impressionism to an American context, finding subjects and moods that resonated with the national experience.

Personal Struggles and Later Years

Despite his professional success, Robert Spencer's personal life was marked by considerable turmoil. He suffered from recurring bouts of severe depression and experienced several nervous breakdowns throughout his adult life. These struggles undoubtedly cast a shadow over his existence and may have contributed to the melancholic undertones present in much of his art.

In 1914, Spencer married Margaret Alexina Harrison Fulton, an accomplished architect and painter in her own right. Margaret was a talented individual, and their home in New Hope, "Rabbit Run," was a testament to their shared artistic sensibilities. However, their marriage was reportedly a difficult one, strained by Spencer's mental health issues and perhaps by the inherent challenges of two creative individuals navigating a shared life.

The cumulative weight of his personal demons and perhaps marital unhappiness proved overwhelming. Tragically, Robert Spencer took his own life on July 10, 1931, in New Hope, Pennsylvania. He was only 51 years old. His death cut short a significant artistic career and left a void in the American art scene.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Robert Spencer's legacy is that of an artist who brought a unique and deeply personal vision to American Impressionism. He expanded the typical subject matter of the movement, turning his gaze towards the mills, factories, and working-class communities that were an integral part of the American landscape but often overlooked by artists seeking more conventionally picturesque scenes. His work is a testament to the beauty that can be found in the everyday, the ordinary, and even the industrial.

His paintings are held in the permanent collections of major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Phillips Collection, the Brooklyn Museum, the Detroit Institute of Arts, and the James A. Michener Art Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, which has a significant collection of works by Pennsylvania Impressionists.

Spencer's art continues to resonate with viewers today for its technical skill, its evocative atmosphere, and its honest portrayal of a particular slice of American life. He captured not just the visual appearance of his subjects, but also their emotional tenor, often imbuing his scenes with a sense of quiet dignity, resilience, or gentle melancholy. He remains a key figure in the New Hope art colony and an important contributor to the rich tapestry of American Impressionism, an artist whose sensitive eye and painterly hand created a lasting and poignant body of work. His ability to find poetry in the prosaic ensures his enduring place in the annals of American art.