Gerrit Albertus Beneker (1882–1934) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in early twentieth-century American art. His work, characterized by a robust realism often infused with impressionistic light and color, captured the spirit of American industry, the dignity of labor, and the coastal life of New England. Beneker's artistic journey reflects a period of profound change in American society, and his canvases serve as compelling documents of an era grappling with industrialization, war, and evolving artistic sensibilities.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, on January 26, 1882, Gerrit Albertus Beneker demonstrated an early aptitude for art. His formative years in the Midwest likely exposed him to a burgeoning industrial landscape, a theme that would later become central to his oeuvre. Seeking formal training, Beneker, like many aspiring artists of his generation, looked eastward to the established art centers of the United States.

His pursuit of artistic excellence led him first to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. There, he studied under prominent figures of the Boston School, including Edmund C. Tarbell and Frank Weston Benson. These artists, known for their elegant portrayals of genteel life rendered with an impressionistic concern for light and atmosphere, undoubtedly shaped Beneker's technical skills and his understanding of color theory. Philip Leslie Hale, another influential instructor at the school, would also have contributed to Beneker's development, emphasizing draftsmanship and academic rigor alongside impressionistic techniques.

Following his studies in Boston, Beneker continued his education at the Art Students League of New York. This institution was a crucible for diverse artistic ideas, attracting students and faculty from various stylistic backgrounds. While in New York, he would have been exposed to the burgeoning Ashcan School, with artists like Robert Henri, John Sloan, and George Bellows championing the depiction of everyday urban life, a stark contrast to the more refined subjects of the Boston School. Though Beneker's style remained distinct, the Ashcan School's focus on contemporary American life may have resonated with his own developing interests.

The Provincetown Influence and a Developing Style

A pivotal moment in Beneker's career was his association with Provincetown, Massachusetts. This picturesque fishing village at the tip of Cape Cod had become a magnet for artists, drawn by its unique light, maritime atmosphere, and vibrant community. Beneker became an active member of the Provincetown Art Association and Colony, a significant center for American art in the early 20th century.

In Provincetown, he studied with Charles Webster Hawthorne, a charismatic teacher and a leading figure in the art colony. Hawthorne was renowned for his vigorous figure painting and his emphasis on capturing the essential character of his subjects, often local fishermen and their families. He encouraged his students to paint directly from life, using broad strokes and a rich palette to convey form and emotion. Hawthorne's influence is evident in Beneker's powerful portrayals of working men and women, imbued with a sense of strength and dignity. Other artists active in Provincetown during this period, such as E. Ambrose Webster and, at times, modernists like Marsden Hartley, contributed to the dynamic artistic environment, though Beneker's path remained more closely aligned with realism and American Impressionism.

Beneker's time in Provincetown solidified his commitment to depicting the American scene. His subjects often included the hardworking fishermen of Cape Cod, their weathered faces and strong hands telling stories of a life lived in close communion with the sea. He captured the bustling activity of the wharves, the play of light on water, and the rugged beauty of the coastal landscape. His style during this period often blended the academic solidity learned in Boston with the looser brushwork and brighter palette encouraged by Hawthorne and the Impressionist movement.

Themes of Labor and Industry

While his coastal scenes are notable, Gerrit Beneker is perhaps best known for his depictions of American laborers and industrial scenes. He possessed a profound respect for the working class and sought to ennoble their contributions to society through his art. This focus set him apart from many of his Boston School contemporaries, who often concentrated on more genteel subjects.

Beneker's industrial paintings are powerful testaments to the burgeoning industrial might of the United States. He ventured into factories and foundries, capturing the drama of steel production, the intensity of the assembly line, and the human element within these often overwhelming environments. His workers are not anonymous cogs in a machine but individuals portrayed with empathy and respect. He saw a certain "romance" in industry, not in a sentimental way, but in the raw power and human ingenuity it represented.

This interest in industrial themes can be seen in the context of a broader, though not always stylistically similar, engagement with modern life by artists like Joseph Pennell, whose etchings documented industrial sites, or later, Reginald Marsh, who captured the teeming energy of urban and industrial America. Beneker's approach, however, often retained a more optimistic and heroic portrayal of the worker compared to the sometimes grittier realism of others.

Representative Works and Artistic Recognition

Several key works exemplify Beneker's artistic concerns and stylistic achievements. "The Price of Fish," for instance, likely depicts the hardy fishermen of Provincetown, capturing the essence of their labor and connection to the sea. His portraits of individual workers, such as "The Lineman" or "The Mill Worker," showcase his ability to convey character and strength through direct, unidealized representation.

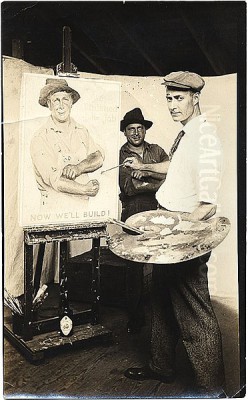

During World War I, Beneker, like many artists, contributed his talents to the war effort by creating patriotic posters. His most famous poster, "Sure, We'll Finish the Job" (1918), depicts a determined American worker rolling up his sleeves, ready to contribute to the industrial output necessary for victory. This image became an iconic representation of the home front's dedication. In this endeavor, he joined other prominent illustrators and painters like Howard Chandler Christy and James Montgomery Flagg, who also produced impactful wartime propaganda.

His work for industrial clients, such as the Hydraulic Pressed Steel Company of Cleveland, Ohio, further cemented his reputation as an artist of industry. These commissions allowed him to explore his themes on a larger scale and bring his vision of the American worker to a wider audience. His paintings were often reproduced in magazines and used in advertising, demonstrating the practical application of his art in a commercial context.

An Inventive Mind: Beyond the Canvas

Interestingly, Beneker's talents were not confined solely to the visual arts. The information provided indicates that Gerrit V. Beneker (presumably the same individual, though the middle initial differs slightly in one reference) collaborated with an R. Keller to invent a hydraulic control valve. This invention, involving a solenoid and a piston to control fluid flow, speaks to a practical, engineering-oriented aspect of his intellect. Such versatility, while not common, is not unheard of among creative individuals who possess both artistic and mechanical aptitudes. This inventive spirit perhaps informed his appreciation for the mechanics and processes of the industries he depicted.

Furthermore, Beneker was engaged in the discourse surrounding art's role in society. His 1929 article, "Art in Education," suggests a thoughtful consideration of how art could contribute to broader educational goals. This reflects a commitment to the value of art beyond its aesthetic qualities, seeing it as a tool for understanding, communication, and personal development. Such writings place him within a tradition of artists who also contributed as thinkers and educators, like Robert Henri with his influential book "The Art Spirit."

Artistic Style: A Blend of Realism and Impressionistic Sensibility

Beneker's artistic style is best characterized as a robust form of American Realism, frequently enlivened by the techniques of Impressionism. His figures are solidly rendered, with a strong sense of anatomy and form, a legacy of his academic training. He was not afraid to depict the grit and toil of labor, yet he always found an inherent dignity in his subjects.

His use of color could be vibrant, especially in his coastal scenes and outdoor portraits, reflecting the Impressionist concern for capturing the effects of natural light. His brushwork was often vigorous and direct, conveying energy and a sense of immediacy. Unlike the more abstract tendencies that were beginning to emerge with modernists like Arthur Dove or Max Weber, Beneker remained committed to representational art, believing in its power to communicate directly with the viewer.

His compositions are typically straightforward and impactful, focusing attention on the central subject, whether it be a solitary worker or a dynamic industrial process. He shared with artists like George Bellows an interest in strong, masculine figures and dynamic action, though Bellows often explored the more aggressive and competitive aspects of urban life, such as boxing.

Interactions and Contemporaries

Throughout his career, Beneker interacted with a wide range of artists. His teachers – Tarbell, Benson, Hale, and Hawthorne – were foundational. His peers in Provincetown formed a supportive and stimulating community. While he may not have been part of a formal "school" beyond his early training, his work aligns with the broader currents of American Realism and American Impressionism.

He would have been aware of the work of other prominent American Impressionists like Childe Hassam and John Henry Twachtman, who, while often focusing on different subject matter, shared a similar interest in capturing the American landscape and the effects of light. Hassam, in fact, also spent time in New England art colonies.

His focus on the American worker also places him in a lineage that includes earlier artists like Thomas Pollock Anshutz, whose "The Ironworkers' Noontime" is a significant precursor in the depiction of industrial labor. While Beneker's style was his own, he was part of a larger conversation in American art about how to represent the nation's rapidly changing identity in the early 20th century.

Later Career, Legacy, and Collections

Gerrit Albertus Beneker continued to paint and exhibit throughout his career, maintaining his focus on themes of labor, industry, and American life. He passed away in Truro, Massachusetts, another Cape Cod town near Provincetown, on October 23, 1934, at the relatively young age of 52.

Today, Beneker's works are held in various public and private collections. The Smithsonian American Art Museum, for example, holds some of his pieces, recognizing his contribution to American art. The Provincetown Art Association and Museum (PAAM) also preserves his legacy as part of its extensive collection representing the art colony's history. His paintings and posters occasionally appear at auction, attesting to a continued appreciation for his work.

His legacy lies in his powerful and empathetic portrayal of the American worker and his ability to find beauty and heroism in the burgeoning industrial landscape. He provided a unique visual record of a transformative period in American history, bridging the gap between academic tradition and a modern, distinctly American subject matter. While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his contemporaries, Gerrit A. Beneker's contribution to American art remains significant for its sincerity, technical skill, and unwavering focus on the human element within the American experience. His work serves as a reminder of the diverse voices and visions that shaped the narrative of American art in the early twentieth century. His exploration of "Art in Education" and even his foray into mechanical invention paint a picture of a multifaceted individual deeply engaged with the world around him.