Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof (1866–1924) stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of Dutch art at the turn of the twentieth century. An artist of remarkable versatility, Dijsselhof made significant contributions as a painter, designer, and craftsman, becoming one of the most prominent proponents of the Nieuwe Kunst, the Dutch iteration of the international Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements. His oeuvre, encompassing intricate furniture, exquisite book designs, innovative batik textiles, and evocative paintings, reflects a deep commitment to craftsmanship, a profound connection to nature, and a unique synthesis of indigenous traditions with international artistic currents. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of an artist whose vision helped shape modern Dutch design.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

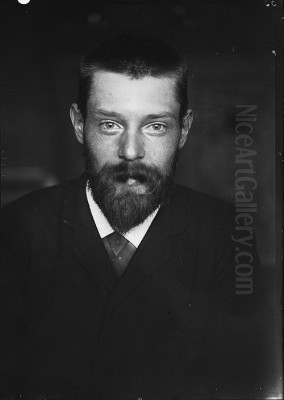

Born on August 2, 1866, in Zwollerkerspel, a rural municipality later incorporated into Zwolle, Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof's early life was rooted in the Dutch countryside. This upbringing likely instilled in him a keen appreciation for the natural world, a theme that would consistently permeate his artistic output. His formal artistic training commenced at the prestigious Royal Academy of Art in The Hague (Koninklijke Academie van Beeldende Kunsten) from 1882 to 1884. This institution, with its long history, provided him with a solid foundation in traditional drawing and painting techniques.

Seeking to further hone his skills and broaden his artistic horizons, Dijsselhof subsequently moved to Amsterdam. The vibrant cultural milieu of Amsterdam, then a burgeoning center for artistic innovation, undoubtedly exposed him to new ideas and influences. He continued his studies, immersing himself in the city's artistic life. It was during this formative period that he began to develop his distinctive style, moving beyond purely academic conventions towards a more personal and decorative mode of expression. The prevailing artistic climate, increasingly receptive to the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement emanating from Britain and the burgeoning Art Nouveau styles from Belgium and France, provided fertile ground for Dijsselhof's evolving aesthetic.

The Rise of Nieuwe Kunst and Dijsselhof's Role

The late nineteenth century witnessed a widespread reaction against the perceived soullessness of industrial mass production and the eclectic historicism that dominated much of Victorian-era design. In the Netherlands, this sentiment coalesced into the Nieuwe Kunst (New Art) movement. This movement, akin to the British Arts and Crafts, the French Art Nouveau, and the German Jugendstil, championed the revival of craftsmanship, the integration of art into everyday life, and the creation of a unified aesthetic across various media. Artists sought to develop a new visual language, often drawing inspiration from natural forms, stylized motifs, and a commitment to honesty in materials and construction.

Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof emerged as a central figure within this transformative movement. He, along with contemporaries such as Theo Nieuwenhuis (1866-1951) and Carel Adolph Lion Cachet (1864-1945), formed a core group that significantly shaped the direction and character of Nieuwe Kunst. These artists often collaborated and shared a common philosophy, believing in the social importance of art and design. They advocated for a holistic approach, where the designer would be involved in all aspects of an object's creation, from initial concept to final execution. This hands-on methodology was seen as essential to restoring dignity to the applied arts and bridging the gap between fine art and craft.

Dijsselhof's contributions to Nieuwe Kunst were multifaceted. He did not confine himself to a single medium but rather explored a wide range of decorative arts. His work in furniture design, bookbinding, embroidery, and wallpaper design all bore the hallmarks of the movement: meticulous attention to detail, high-quality materials, and an emphasis on organic, flowing lines or stylized geometric patterns derived from nature. His commitment to these principles helped to define the visual identity of Dutch Art Nouveau.

Masterpieces in Book Design: Kunst en Samenleving

One of Dijsselhof's most celebrated achievements in the realm of applied arts is his design for the Dutch translation of Walter Crane's influential book, "The Claims of Decorative Art." Published in 1893 as Kunst en Samenleving (Art and Society), this publication is considered a landmark in Dutch book design and a quintessential example of Nieuwe Kunst aesthetics. Walter Crane (1845-1915) was a leading figure in the English Arts and Crafts movement, and his writings, advocating for the social role of art and the importance of decorative arts, resonated deeply with Dutch artists like Dijsselhof.

For Kunst en Samenleving, Dijsselhof was responsible not only for the cover but also for the typography, vignettes, and overall layout. The cover itself is a masterpiece of integrated design, featuring stylized floral motifs and elegant lettering, all meticulously executed. His approach to book design treated the book as a total work of art, where every element contributed to a harmonious whole. This holistic vision was a direct reflection of the ideals espoused by William Morris (1834-1896), the spiritual father of the Arts and Crafts movement, who had revolutionized book design with his Kelmscott Press. Dijsselhof's work on Kunst en Samenleving demonstrated a profound understanding of these principles, adapting them to a distinctly Dutch sensibility. The intricate patterns and careful balance of form and space in his book designs set a new standard and influenced a generation of Dutch graphic artists and typographers.

Innovations in Batik and Textile Art

Beyond book design, Dijsselhof made pioneering contributions to the art of batik in the Netherlands. Batik, an ancient wax-resist dyeing technique originating from Indonesia (then the Dutch East Indies), captivated several Dutch artists at the turn of the century. They were drawn to its rich colors, intricate patterns, and the unique textural qualities of the dyed fabric. Dijsselhof, along with Lion Cachet and Chris Lebeau (1878-1945), was at the forefront of adapting and popularizing this technique for European artistic purposes.

A significant challenge in using traditional batik dyes was their tendency to fade. Dijsselhof, demonstrating his characteristic thoroughness and innovative spirit, collaborated with chemical experts to improve the dye technology. This allowed him to create large-scale batik works, such as screens and wall hangings, with more permanent and vibrant colors. His batik designs often featured stylized representations of flora and fauna – fish, birds, and plants – rendered with a remarkable sense of pattern and rhythm. These works were inspired by his observations of nature, often from aquariums and botanical gardens like Amsterdam's Artis Zoo, but also showed a clear influence from Japanese art, particularly Ukiyo-e woodblock prints by artists like Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), which were admired for their compositional elegance and stylized depiction of natural subjects.

Dijsselhof's batik pieces were not mere decorative novelties; they were considered significant artistic statements. They demonstrated how a traditional, "exotic" craft could be transformed into a sophisticated medium for modern artistic expression. His success in this field helped to elevate textile art within the hierarchy of the arts in the Netherlands and showcased the Nieuwe Kunst ideal of embracing diverse sources of inspiration.

Furniture and Interior Design: The Dijsselhofkamer

Dijsselhof's talents extended to the realm of furniture and interior design, where he sought to create harmonious and aesthetically unified environments. His furniture pieces are characterized by their solid construction, often in oak, and their distinctive carved or inlaid decorations. These decorations typically featured the stylized natural motifs that were his signature, executed with exceptional woodworking skill. He believed that furniture should be both functional and beautiful, an integral part of a thoughtfully designed living space.

Perhaps the most famous and comprehensive example of Dijsselhof's interior design work is the Dijsselhofkamer (Dijsselhof Room). This remarkable ensemble was commissioned by Dr. Willem van Hoorn, an Amsterdam dermatologist, for his home. Designed and executed between 1898 and 1900, the room was intended as a Gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art – where every element, from the wall paneling and furniture to the textiles and lighting fixtures, was conceived by Dijsselhof as part of an integrated whole. The room featured intricately carved woodwork, stained glass, and, significantly, large batik panels designed by Dijsselhof and executed in collaboration with his wife, Maria Wilhelmina Verena Keucheus, who was also an accomplished artist.

Tragically, Dr. van Hoorn passed away in 1901, shortly after the room's completion, and thus never fully enjoyed this unique space. The room was later acquired by another physician, Dr. P. Verhagen. After Dr. Verhagen's death, his heirs generously donated the entire Dijsselhofkamer to the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag (now Kunstmuseum Den Haag) in 1929. It remains one of the museum's most treasured exhibits, a testament to Dijsselhof's holistic design vision and a prime example of Nieuwe Kunst interior architecture. The room stands alongside the architectural and design achievements of contemporaries like H.P. Berlage (1856-1934), whose own work, such as the Beurs van Berlage (Amsterdam Stock Exchange), also embodied the principles of rational construction and integrated design.

Painting and Other Artistic Pursuits

While Dijsselhof is perhaps best known for his contributions to the decorative arts, he was also a painter throughout his career. His paintings often depict landscapes, floral studies, and animal subjects, particularly fish and birds, rendered with a keen eye for detail and a subtle, often Symbolist-tinged atmosphere. Works like "Two Snails" (1892) are notable for their almost scientific observation combined with a decorative sensibility, revealing intricate, fractal-like patterns in nature. His "Tulip Field" paintings capture the iconic Dutch landscape with a sensitivity to color and light.

His painterly style, while distinct from the more avant-garde movements of his time, such as the burgeoning Post-Impressionism of Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) or the Amsterdam Impressionism of George Hendrik Breitner (1857-1923) and Isaac Israëls (1865-1934), shared the Nieuwe Kunst emphasis on careful composition and decorative effect. His paintings often feel like extensions of his design work, sharing a common vocabulary of stylized natural forms and a meticulous approach to execution. He also created embroideries and wallpaper designs, further demonstrating his versatility and his commitment to beautifying all aspects of the lived environment.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Philosophy

Dijsselhof's artistic style is characterized by a harmonious blend of meticulous craftsmanship, stylized naturalism, and a strong decorative sense. His work consistently demonstrates a deep reverence for the natural world, which he studied with an almost scientific intensity. However, his depictions of nature were rarely purely realistic; instead, he translated organic forms into elegant, often symmetrical patterns and rhythmic lines that suited the decorative purpose of the object or surface.

A significant influence on his work, as noted, was Japanese art. The compositional strategies, flattened perspectives, and stylized representations of nature found in Ukiyo-e prints resonated with many Art Nouveau artists, including Dijsselhof. This influence is evident in the asymmetrical arrangements, the focus on line, and the decorative use of empty space in some of his designs, particularly in his batik work.

Underpinning Dijsselhof's diverse artistic output was a philosophy rooted in the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement. He believed in the intrinsic value of handmade objects and the importance of the artist-craftsman's direct involvement in the production process. This stood in stark contrast to the anonymity and mechanization of industrial manufacturing. For Dijsselhof and his Nieuwe Kunst colleagues, art was not merely an aesthetic pursuit but also had a social and ethical dimension. By creating beautiful, well-crafted objects for everyday use, they aimed to enhance the quality of life and foster a greater appreciation for art in society. This aligns with the thinking of other Dutch artists concerned with monumental and community art, such as Antoon Derkinderen (1859-1925) and Johan Thorn Prikker (1868-1932), who also sought to integrate art into public and private life.

Collaborations and the Spirit of Nieuwe Kunst

The Nieuwe Kunst movement was characterized by a spirit of collaboration and shared ideals. Dijsselhof worked closely with fellow artists who were similarly dedicated to renewing the applied arts. His association with Theo Nieuwenhuis and Adolph Lion Cachet was particularly significant. Together, they formed a kind of triumvirate that spearheaded many of the innovations in Dutch Art Nouveau design. They often exhibited together and shared a common workshop space for a period, fostering an environment of mutual influence and support.

The collaboration with his wife, Maria Wilhelmina Verena Keucheus, on projects like the batik panels for the Dijsselhofkamer, highlights the often-overlooked contributions of women artists within these movements. The creation of such complex, integrated interiors frequently involved multiple skilled individuals working towards a unified vision. Other key figures in the broader Nieuwe Kunst circle included the architect and designer K.P.C. de Bazel (1869-1923), whose work also emphasized rational design and craftsmanship, and the versatile graphic artist and designer Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita (1868-1944), who, like Dijsselhof, made significant contributions to book art and printmaking. The collective energy of these artists helped to create a vibrant and distinctive chapter in Dutch art history.

Later Years and Legacy

In his later years, Dijsselhof increasingly focused on painting, though he continued to undertake design projects. He passed away on June 14, 1924, in Overveen. While the overtly decorative style of Art Nouveau had begun to wane by the 1920s, giving way to the more austere aesthetics of modernism and Art Deco, Dijsselhof's contributions left an indelible mark on Dutch design.

His emphasis on craftsmanship, quality materials, and integrated design laid important groundwork for subsequent developments in Dutch modernism. The integrity of his approach and the sheer beauty of his creations ensured their lasting appeal. Art critics and historians today recognize Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof as a master of Dutch Art Nouveau, an artist who successfully synthesized diverse influences into a unique and coherent personal style. His work is celebrated for its technical brilliance, its aesthetic refinement, and its embodiment of the highest ideals of the Nieuwe Kunst movement.

The Dijsselhofkamer remains a powerful testament to his vision, allowing contemporary audiences to experience the immersive quality of a Nieuwe Kunst interior. His book designs are prized by collectors and studied by graphic designers, while his batik works are recognized as important examples of the cross-cultural exchange that enriched European art at the turn of the century. His paintings, too, are appreciated for their quiet beauty and meticulous observation.

Conclusion: An Enduring Influence

Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof was more than just a skilled craftsman or a talented painter; he was an artist with a comprehensive vision. He believed in the power of art to transform everyday life and dedicated his career to creating objects and environments of exceptional beauty and integrity. As a leading figure of Nieuwe Kunst, he played a crucial role in shaping a distinctly Dutch response to the international call for artistic renewal at the dawn of the modern era. His legacy endures in his exquisite works, which continue to inspire admiration for their intricate detail, their harmonious forms, and their profound connection to the enduring beauty of the natural world. Through his diverse contributions, Dijsselhof secured his place as one of the most important and influential Dutch artists of his generation, a true luminary whose light continues to shine.