Giacomo Grosso stands as a significant, if sometimes controversial, figure in Italian art during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. An artist of considerable technical skill and ambition, he navigated the shifting artistic currents of his time, leaving behind a body of work that encompassed academic precision, Realist observation, and a flair for the dramatic that occasionally courted scandal. His legacy is primarily tied to his powerful portraiture and his sensational, large-scale compositions that captivated and sometimes shocked the public.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Born in 1860 in Cambiano, a small town near Turin in the Piedmont region of Italy, Giacomo Grosso's artistic journey began in a country still forging its modern identity after the Risorgimento. The artistic environment was rich, with regional schools and traditions vying with emerging national and international trends. Grosso's formal artistic training took place at the prestigious Accademia Albertina in Turin, one of Italy's leading art academies.

At the Accademia Albertina, Grosso would have been immersed in a curriculum that emphasized rigorous academic training. This included drawing from plaster casts of classical sculptures, life drawing, anatomy, perspective, and the study of Old Masters. Such an education was designed to equip artists with impeccable technical skills, a strong foundation that would serve Grosso throughout his career. His professors, likely figures such as Andrea Gastaldi, would have instilled in him the values of verismo (a form of Italian Realism) and the importance of accurate representation, even as Romantic and Symbolist ideas were beginning to permeate the European art scene. This academic grounding is evident in the solidity of his forms and the confidence of his brushwork.

Rise as a Portraitist and Painter of Modern Life

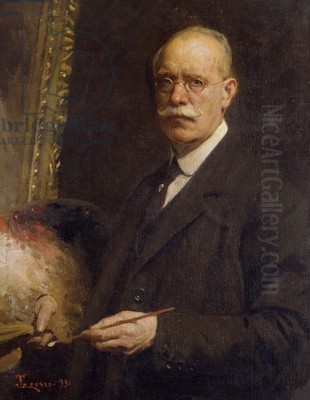

Grosso quickly established himself as a painter of considerable talent, particularly in the realm of portraiture. In an era before the widespread use of photography for formal likenesses, painted portraits were still highly valued by the aristocracy, the burgeoning bourgeoisie, and prominent public figures. Grosso excelled in this genre, capturing not only the physical appearance of his sitters but also conveying a sense of their personality and social standing. His portraits were often characterized by their elegant compositions, rich textures, and a psychological insight that elevated them beyond mere likenesses.

His sitters included notable personalities from Italian society, and his reputation extended beyond national borders. He was sought after for his ability to imbue his subjects with an air of dignity and importance, often employing dramatic lighting and opulent settings. This success in portraiture provided him with financial stability and a prominent position within the Italian art world. Artists like Giovanni Boldini, with his flamboyant portrayals of Belle Époque society, or the more introspective work of Antonio Mancini, offer contemporary points of comparison for the diverse approaches to portraiture in Italy at the time.

Beyond portraits, Grosso also engaged with genre scenes, landscapes, and still lifes, demonstrating a versatile command of different subjects. His style, while rooted in academic Realism, often showed an awareness of broader European trends. There's a certain naturalism in his work that aligns with the broader Realist movement championed by artists like Gustave Courbet in France, though Grosso's output was generally more polished and less overtly political than that of some of his French counterparts.

The Scandal of Il Supremo Convegno at the 1895 Venice Biennale

The pivotal moment that cemented Giacomo Grosso's fame, and notoriety, came in 1895 at the inaugural Venice Biennale. This new international art exhibition was intended to showcase the best of contemporary art, and Grosso submitted a monumental and audacious painting titled Il Supremo Convegno (The Supreme Meeting, also referred to as The Final Tryst or Ultimate Meeting).

The painting depicted a dimly lit interior, possibly a crypt or chapel, where a coffin lay in the center. Around and upon this coffin were several nude female figures, their bodies rendered with sensual realism. One figure, in particular, was shown straddling the coffin, her expression ambiguous, perhaps a mixture of grief, ecstasy, or defiance. The scene was undeniably provocative, blending themes of death, eroticism, and the sacred in a manner that was bound to cause a stir.

The work immediately became the succès de scandale of the Biennale. The Count of Sambuy, one of the organizers, reportedly advocated for its prominent display, while the mayor of Venice, Riccardo Selvatico, expressed concerns about its potential to offend public morality. The controversy escalated, drawing criticism from conservative quarters and even, reportedly, the Vatican, which was said to have demanded its removal. The subject matter – nude women in such close, almost celebratory, proximity to a symbol of death and within a seemingly sacred space – challenged conventional notions of decorum and religious sensibility.

Despite the pressure, the Biennale organizers did not entirely remove the painting. Instead, it was moved to a more secluded room, a compromise that perhaps only fueled public curiosity. The ensuing debate in the press and among the public was intense. Was it a masterpiece of daring modern art, or a tasteless affront to decency? A committee of intellectuals in Venice discussed the painting's merits and its potential violation of public morals, ultimately deciding to allow its continued exhibition, recognizing its artistic value.

Ultimately, Il Supremo Convegno proved immensely popular with the public, reportedly winning a public prize or acclaim at the exhibition. The scandal, far from harming Grosso's career, propelled him to international fame. It highlighted the tensions of the fin-de-siècle period, where traditional values clashed with emerging modernist sensibilities. The painting's themes resonated with Symbolist undercurrents seen in the work of artists like Gustav Klimt or Edvard Munch, who also explored themes of life, death, and sensuality, albeit often in a less overtly realistic style. Grosso's work, however, retained a strong connection to the academic tradition of the nude, reminiscent of Salon painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau or Jean-Léon Gérôme, but infused with a modern, unsettling psychological drama.

Artistic Style: Realism, Naturalism, and a Touch of Art Nouveau

Grosso's artistic style is most accurately described as a form of late academic Realism or Naturalism, often infused with a dramatic, almost theatrical, sensibility. His technical mastery, honed at the Accademia Albertina, was evident in his precise drawing, his skillful modeling of form, and his rich use of color and texture. He had a particular talent for rendering fabrics, flesh tones, and the interplay of light and shadow, which lent a tactile quality to his paintings.

While firmly rooted in representational art, some of Grosso's works, particularly those featuring female figures, show subtle influences of Art Nouveau (or "Stile Liberty" as it was known in Italy). This can be seen in the sinuous lines of his figures, a certain decorative quality in his compositions, and an emphasis on sensuality that was characteristic of the Art Nouveau aesthetic. However, he never fully embraced the more stylized and ornamental aspects of Art Nouveau seen in artists like Alphonse Mucha or Aubrey Beardsley. Instead, these elements were integrated into his fundamentally Realist framework.

His approach to Naturalism was less about social critique, as seen in the work of some French Naturalists or Italian Verismo painters like Francesco Paolo Michetti or the earlier Macchiaioli like Telemaco Signorini, and more focused on creating visually compelling and emotionally resonant scenes. His large-scale compositions, like Il Supremo Convegno, were designed to make an impact, employing dramatic narratives and a heightened sense of realism to engage the viewer.

Other Notable Works and International Recognition

While Il Supremo Convegno remains his most famous work due to its controversial debut, Grosso produced a substantial oeuvre throughout his career. Another significant painting is La Nuda (The Nude), which further exemplifies his skill in depicting the female form. This work, like many of his nudes, combines academic precision with a palpable sensuality. La Nuda was eventually acquired by the Museo Civico di Brescia, indicating its recognized artistic merit.

Grosso's reputation was not confined to Italy. He participated in numerous international exhibitions, including those in Paris, Munich, and even as far afield as Buenos Aires and São Paulo. His participation in these prestigious venues underscores his standing in the international art scene of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In Buenos Aires, for instance, he found patrons among the wealthy Argentine elite, for whom he painted portraits, further demonstrating the international appeal of his polished, academic style.

His success at these exhibitions helped to solidify his position and brought Italian art to a wider audience. He was a contemporary of other Italian artists who were also gaining international recognition, such as Giovanni Segantini, whose Divisionist landscapes and Symbolist themes offered a different, but equally compelling, vision of modern Italian art, or Gaetano Previati, another key figure in Italian Divisionism and Symbolism.

Grosso the Educator: A Pivotal Role at the Accademia Albertina

Beyond his career as a practicing artist, Giacomo Grosso made significant contributions as an educator. He returned to his alma mater, the Accademia Albertina in Turin, as a professor of painting. In this role, he influenced a new generation of artists, passing on the technical skills and artistic principles he had mastered.

His teaching would have emphasized the importance of solid draftsmanship, a thorough understanding of anatomy, and the ability to create convincing representations of the human form and the natural world. Given his own success, his students would have looked to him as a model of a successful professional artist.

One of his most notable students was Giacomo Balla. Balla, who studied under Grosso in the 1890s, would later become a leading figure in the Futurist movement, one of the most radical avant-garde movements of the early 20th century. While Balla's mature Futurist style, with its emphasis on dynamism, speed, and the fragmentation of form, seems a world away from Grosso's academic Realism, Grosso's instruction would have provided Balla with a crucial foundation in the fundamentals of painting. The trajectory of Balla, from Grosso's tutelage to Futurism, illustrates the rapid pace of artistic change in the early 20th century, where foundational academic training could still serve as a springboard for radical innovation. Other artists who passed through the Accademia Albertina during this period would also have benefited from the prevailing artistic environment shaped by figures like Grosso.

Grosso's commitment to teaching and his long tenure at the Accademia Albertina demonstrate his dedication to the continuation of artistic traditions, even as he himself was capable of pushing the boundaries of public taste. He was also involved with artistic organizations in Turin, such as the "Promotriestini" (Turin Promoters), which aimed to promote art and culture in the city.

Later Career and Enduring Legacy

Giacomo Grosso continued to paint and exhibit throughout the early decades of the 20th century, adapting to some extent to changing tastes but largely remaining true to his established style. He lived until 1938, witnessing profound transformations in the art world, including the rise of Cubism, Futurism, Surrealism, and various forms of abstraction. While his own work did not embrace these radical departures, he remained a respected figure, particularly in Turin and the Piedmont region.

His legacy is complex. On one hand, he can be seen as a highly skilled academic painter, a master of traditional techniques who excelled in portraiture and grand narrative compositions. His work represents a continuation of the Salon tradition, valuing craftsmanship, realism, and a certain degree of idealization. Artists like Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, another contemporary, also worked on large-scale, socially relevant canvases, though Pellizza's Divisionist technique and focus on peasant life differed significantly from Grosso's more bourgeois and sometimes sensational subjects.

On the other hand, Grosso was not merely a conservative academic. His willingness to tackle controversial subjects, as demonstrated by Il Supremo Convegno, shows an artist who was aware of the power of art to provoke and to engage with contemporary anxieties and fascinations. The scandal surrounding that painting ensured his place in the annals of the Venice Biennale and in the broader history of late 19th-century art.

Today, Grosso's works are held in various Italian museums, including the Galleria Civica di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Turin and the Pinacoteca dell'Accademia Albertina. These collections allow for a reassessment of his contribution to Italian art. While perhaps overshadowed in broader art historical narratives by the more revolutionary avant-garde movements that followed, Grosso remains an important figure for understanding the artistic climate of Italy at the turn of the century – a period of transition, where academic traditions coexisted and sometimes clashed with emerging modernist impulses. He represents a strand of Italian art that maintained a high level of technical proficiency while exploring themes that resonated with the sensibilities of the fin-de-siècle. His influence as a teacher also ensured that his impact extended to the next generation of artists, even those who would ultimately take very different artistic paths.

Conclusion: An Artist of His Time

Giacomo Grosso was, in many ways, an artist perfectly attuned to his time. He possessed the technical skill admired by the academies and the burgeoning middle and upper classes who commissioned portraits. Simultaneously, he had a flair for the dramatic and an understanding of how to capture public attention, sometimes through controversy, which aligned with the sensationalist aspects of fin-de-siècle culture.

His career spanned a period of immense artistic change, from the dominance of academic Realism to the explosion of the avant-garde. While he remained largely within the bounds of representational art, his work was not static. It reflected an engagement with contemporary themes and a willingness to push boundaries, particularly in his exploration of the female nude and in the psychological intensity of some of his compositions.

As a professor at the Accademia Albertina, he played a crucial role in shaping young artists, providing them with the foundational skills necessary for their own diverse careers. His most famous work, Il Supremo Convegno, remains a fascinating example of how art can intersect with public morality, scandal, and popular acclaim, securing Giacomo Grosso's place as a memorable and significant painter in the rich tapestry of Italian art history. His ability to blend academic tradition with a modern sensibility for drama and provocation makes him a compelling figure worthy of continued study and appreciation.