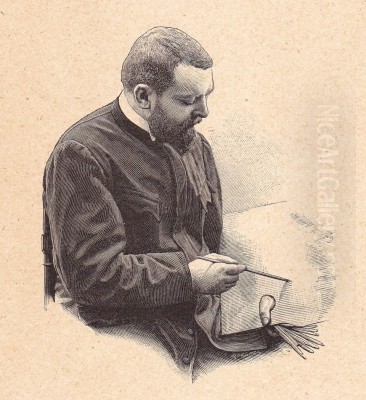

Henri Gervex stands as a significant figure in French art during the latter half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Paris on December 10, 1852, and passing away in the same city on June 6, 1929, Gervex navigated the complex artistic landscape of his time, skillfully blending the rigorous techniques of academic painting with the burgeoning interest in modern life and the stylistic innovations of Impressionism. His career, marked by both official recognition and public scandal, offers a fascinating window into the cultural dynamics of the Belle Époque. He emerged from an artistic family, setting the stage for a life dedicated to the visual arts.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Gervex's formal artistic education took place at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the epicenter of academic art training in France. There, he studied under several influential masters who shaped his early development. Among his most notable teachers was Alexandre Cabanel, a highly respected figure known for his polished historical and mythological paintings, epitomizing the academic style favored by the official Salon. Cabanel's emphasis on precise drawing, smooth finish, and idealized forms provided Gervex with a strong technical foundation.

He also received instruction from Pierre-Nicolas Brisset and Eugène Fromentin. Fromentin, particularly, was a renowned painter and writer, known for his Orientalist scenes inspired by his travels in North Africa. Studying with Fromentin likely exposed Gervex to different subject matter and perhaps a richer palette, complementing the stricter academicism of Cabanel. Further guidance came from artists like Jean-Louis Forain and Fernand Cormon, both significant figures in the Parisian art world, and Emmanuel Damas, ensuring a comprehensive grounding in the dominant artistic practices of the era. This training instilled in him a mastery of traditional techniques that would underpin his work throughout his career.

Academic Roots and Early Career

Gervex launched his public career in 1873, initially adhering closely to the conventions expected of a promising young artist trained in the academic system. His early works often explored mythological and literary themes, subjects favored by the Salon juries and the art establishment. These paintings showcased his technical proficiency, particularly in the rendering of the human form and the creation of balanced compositions. An example from this period is Diane et Endymion (Diana and Endymion), painted in 1875 and exhibited in Angoulême, now housed in the city's Musée des Beaux-Arts. Such works demonstrated his alignment with the academic tradition inherited from teachers like Cabanel.

During these formative years, Gervex focused on building his reputation through participation in the official Paris Salon, the primary venue for artists seeking recognition and patronage. Success at the Salon could lead to state purchases, commissions, and critical acclaim. Gervex's early submissions aimed to meet the Salon's standards, emphasizing historical or mythological narratives, careful execution, and a certain decorum. His initial output reflected a commitment to the established artistic hierarchy, positioning him as a talented practitioner within the academic fold before his later, more controversial, explorations of modern life.

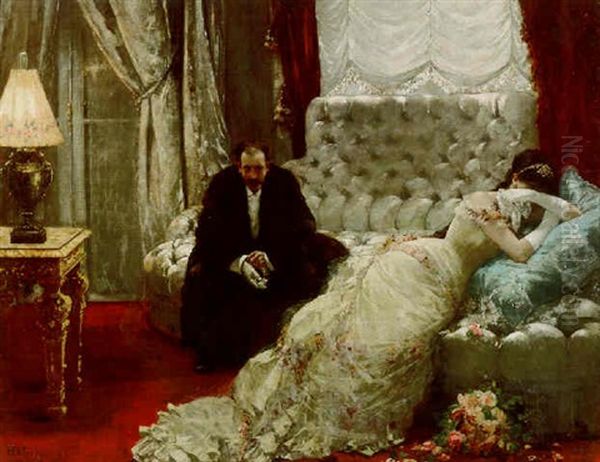

The Scandal of Rolla

The pivotal moment that thrust Gervex into the public eye arrived in 1878 with his painting Rolla. Based on a poem by Alfred de Musset, the work depicted a dramatic scene: the young, dissipated Jacques Rolla standing by a window, looking away from the bed where his lover, Marion, a prostitute, lies asleep amidst discarded clothing and jewelry after their night together. The poem narrates Rolla's subsequent suicide after spending his last inheritance on this encounter. Gervex's rendering was explicit for its time, particularly the detailed depiction of Marion's nude form, sprawled sensuously across the bed.

The painting was submitted to the Paris Salon of 1878, but the jury rejected it, deeming it "immoral" due to its subject matter and the frankness of the nudity. The controversy wasn't just about the nakedness itself – academic nudes were common – but about the context: this was clearly a contemporary prostitute, not a timeless nymph or goddess. Details like her discarded corset, dress, and garters emphasized her profession and the modernity of the scene, stripping away mythological or historical pretext. The rejection caused a sensation, especially since Gervex was already an award-winning artist.

Refusing to be silenced, Gervex arranged for Rolla to be exhibited publicly for three months in the window of a Parisian art dealer on the Chaussée d'Antin. The display attracted enormous crowds, generating intense discussion and debate in the press. Critics were divided: some praised its technical skill and powerful realism, acknowledging the artistic merit, while others condemned its perceived vulgarity and violation of social decorum. Ironically, the scandal cemented Gervex's fame far more effectively than a conventional Salon acceptance might have. Rolla became one of his most famous works, marking a turn towards modern subjects and demonstrating his willingness to challenge artistic conventions.

Embracing Modern Life and Realism

Following the notoriety of Rolla, Gervex increasingly turned his attention away from purely mythological or historical subjects towards depictions of contemporary Parisian life. While he never fully abandoned his academic training, his focus shifted to capturing the realities, complexities, and sometimes the darker aspects of the modern urban experience. This move aligned him broadly with the Realist current in French art, which sought to portray everyday life and social conditions without idealization. His work began to reflect the social transformations and the vibrant, often challenging, atmosphere of late 19th-century Paris.

A key work exemplifying this shift is Dr. Péan at the Salpêtrière, also known as Avant l'opération (Before the Operation), painted in 1887. This large canvas depicts the renowned surgeon Dr. Jules-Émile Péan demonstrating a surgical procedure (likely the invention of the hemostatic clamp) before an audience of students and colleagues at the famous Salpêtrière hospital. The painting is a striking example of modern realism applied to a scientific setting. Gervex captures the intensity of the operating theatre, the focused expressions of the medical professionals, and the stark reality of the patient under anesthesia. It was often compared to Rembrandt van Rijn's The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, serving as a modern counterpart focused on contemporary medical progress and practice.

Gervex also explored other facets of Parisian society, including its leisure and nightlife. Works like L’Alcoolique (The Alcoholic), mentioned in biographical summaries, likely delved into the social issues accompanying urban growth. His paintings often captured the fashionable gatherings, the cafes, theatres, and intimate moments of the Parisian bourgeoisie and demimonde, reflecting his keen observation of the social dynamics of his time. He became adept at portraying the specific atmosphere and character of modern Paris, blending his academic skill with a more immediate, observational approach.

Impressionism's Orbit and Artistic Connections

While Gervex maintained strong ties to the academic tradition, he was not isolated from the revolutionary artistic developments happening around him, particularly the rise of Impressionism. He moved in circles that included prominent Impressionist painters and was receptive to some of their innovations, particularly their brighter palettes and interest in capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere. Around 1876, he reportedly joined the Impressionist circle, indicating a period of close association and exchange of ideas, even if he never fully adopted their stylistic principles or exhibited with them in their independent shows.

His connections with leading figures like Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas are particularly noteworthy. Manet, a pivotal figure bridging Realism and Impressionism, and Degas, known for his unique depictions of modern life (dancers, racetracks, cafes), were both friends and, at times, complex rivals. Gervex associated with both artists, absorbing aspects of their approaches to modern subject matter and composition. The influence can be seen in the increased naturalism, looser brushwork in certain passages, and contemporary themes found in Gervex's work from the late 1870s onwards. He also knew Camille Pissarro, another core member of the Impressionist group.

However, Gervex charted his own course. Unlike the core Impressionists who often prioritized capturing subjective visual sensations over precise detail, Gervex typically retained a commitment to solid drawing and structure learned from his academic training. His relationship with Impressionism was more one of selective adaptation than full conversion. He successfully integrated elements of modern style – brighter colors, contemporary subjects, a sense of immediacy – into a framework that remained accessible and appealing to a broader audience, including Salon juries and official patrons, after the initial Rolla controversy subsided. His position allowed him to act as a bridge between the established art world and the avant-garde. Other contemporaries exploring modern Paris included Gustave Caillebotte, while figures like Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Berthe Morisot were central to the Impressionist movement Gervex interacted with.

Monumental Projects and Collaborations

Beyond easel painting, Gervex undertook several large-scale decorative projects and collaborations, demonstrating his versatility and standing within the French art establishment. One of the most ambitious was the Panorama de l’Histoire du Siècle (Panorama of the History of the Century), created for the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris. This monumental work, celebrating the centenary of the French Revolution, depicted key figures and events from 1789 to 1889. Gervex collaborated on this massive undertaking with the Belgian painter Alfred Stevens, a fellow Parisian resident known for his elegant depictions of fashionable women.

The collaboration reportedly involved a division of labor: Gervex was primarily responsible for painting the numerous male historical figures, while Stevens focused on the female figures and intricate details of costume and setting. Creating such panoramas was a popular but demanding genre in the 19th century, requiring considerable organizational skill, historical research, and technical prowess to execute on a vast scale. The Panorama was a major attraction at the Exposition, showcasing Gervex's ability to handle complex historical narratives and large compositions, reinforcing his public profile.

Gervex also received commissions for decorative paintings in important public buildings. He contributed decorative panels for spaces such as the Mairie (City Hall) of the 19th arrondissement in Paris and participated in the decoration of other civic spaces, including potentially the grand Hôtel de Ville (Paris City Hall) itself. These commissions were prestigious assignments, typically awarded to artists held in high regard by the state and municipal authorities. They further solidified his reputation as an artist capable of working in the grand tradition of public art, blending historical or allegorical themes with his characteristic realistic style.

Official Recognition and Later Career

Despite the early scandal surrounding Rolla, Gervex achieved significant official recognition throughout his career. He continued to exhibit regularly at the Paris Salon, where his technical skill and increasingly popular modern subjects earned him accolades and awards. His ability to navigate between academic expectations and modern sensibilities proved advantageous. A major sign of his established status was his award of the Legion of Honour, one of France's highest civilian decorations, acknowledging his contributions to French art.

His later career saw him continue to produce portraits, genre scenes, and further large-scale commissions. He remained a sought-after portraitist, capturing likenesses of prominent figures of the era. Works like Une Soirée au Pré-Catelan (An Evening at the Pré-Catelan), painted in 1909, depict the elegant social life of the Parisian elite in fashionable settings, showcasing his continued engagement with contemporary society. This painting captures a specific dinner party at a famous Bois de Boulogne restaurant, filled with recognizable personalities of the time.

He also tackled historical events of his own time. The Coronation of Nicholas II documented the lavish ceremony held in Moscow in 1896, a commission likely reflecting his international reputation. The painting The Distribution of Awards at the Palais de l'Industrie (1889) commemorated an official event linked to the Exposition Universelle. He also painted Nana (1885), likely inspired by the famous character from Émile Zola's novel, further demonstrating his interest in contemporary literature and social commentary. These later works confirm his status as a successful, established artist adept at chronicling various aspects of his time, from high society to historical moments.

Gervex's Distinctive Style: A Synthesis

Henri Gervex's artistic style is best understood as a synthesis of different influences, reflecting the transitional nature of French art in his time. He began firmly rooted in the Academic tradition, mastering anatomy, perspective, and composition under teachers like Cabanel. This foundation provided his work with a consistent solidity and technical polish, even when exploring modern themes. His early mythological works exemplify this academic approach.

The Rolla scandal marked a turning point, pushing him towards Realism and the depiction of contemporary life. He embraced modern subjects with a directness that could be provocative, capturing the social fabric of Paris – from operating theatres (Dr. Péan) to high society gatherings (Pré-Catelan) and the lives of ordinary or marginalized figures. This realist impulse was tempered by his academic training, resulting in works that were often more polished and less gritty than those of some other Realists.

Furthermore, Gervex absorbed elements from Impressionism, particularly in his handling of light and color, and sometimes employed looser brushwork, especially in backgrounds or less critical areas of a composition. While he rarely dissolved form to the extent of Monet or Pissarro, his palette brightened, and his scenes often possess a sense of immediacy characteristic of Impressionist concerns. He was also noted for his interest in new technologies, reportedly using photography as a tool in his preparatory process, reflecting a modern engagement with visual aids that artists like Degas also explored. His style, therefore, represents a unique blend: academic structure, realist subject matter, and impressionistic touches, adapted to create accessible yet modern images.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Henri Gervex left a notable legacy within the context of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. His primary influence lies in his successful navigation and bridging of the seemingly opposed worlds of academic art and modern painting. He demonstrated that it was possible to incorporate contemporary subjects and innovative stylistic elements without entirely abandoning traditional techniques and structures. This made his work accessible and popular during his lifetime and provided a model for other artists seeking a middle ground.

As an educator, having taught and held positions within the art establishment (including involvement with the École des Beaux-Arts), he likely influenced a subsequent generation of artists, passing on his blend of technical skill and modern sensibility. His numerous public commissions, such as the Panorama and municipal decorations, ensured his work had a visible presence and contributed to the visual culture of the French Third Republic.

His paintings remain valuable historical documents, offering vivid insights into Belle Époque Paris – its medical advancements, social rituals, fashions, and underlying tensions. Works like Rolla continue to spark discussion about art, morality, and censorship, while Dr. Péan stands as a powerful image of scientific modernity. Though perhaps overshadowed in art history narratives by the more radical Impressionists like Monet or Degas, or the Post-Impressionists like Van Gogh or Gauguin, Gervex played a significant role in his time. He was a chronicler of modernity, a master technician, and a figure who reflected the complex artistic dialogues of an era undergoing profound change. His career highlights the diversity of artistic practice beyond the avant-garde, showcasing the enduring power of skillfully executed representational painting engaging with the contemporary world.