Paul Émile Chabas (1869–1937) stands as a fascinating figure in French art history, an artist whose considerable skill and academic success became inextricably linked with, and arguably overshadowed by, a single, sensational controversy. A painter and illustrator born in Nantes, France, Chabas navigated the Parisian art world at a time of immense change, adhering largely to the established traditions of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, of which he became a member. His name, however, resonates most strongly not just for his numerous accolades but for the international furor ignited by his most famous painting, Matinée de Septembre (September Morn).

Trained within the rigorous French academic system, Chabas developed a refined technique perfectly suited to the tastes of the official Salon. His legacy is primarily built upon his depictions of the female nude, often young women situated within idyllic natural landscapes, rendered with a characteristic softness of light and delicate coloration. While he achieved significant recognition within the French art establishment, his story serves as a compelling case study of artistic reputation, public morality, and the unpredictable nature of fame in the early 20th century.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in the Academic Tradition

Paul Émile Chabas was born on March 7, 1869, in Nantes, a vibrant port city in western France. Coming from a family that supported the arts – his elder brother, Maurice Chabas, would also become a notable Symbolist painter – Paul showed early promise. Seeking the finest artistic education available, he moved to Paris to study at the prestigious Académie Julian and later likely integrated into circles associated with the École des Beaux-Arts, the cornerstone of official art training in France.

His most influential mentors were two giants of late 19th-century French Academic painting: William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Tony Robert-Fleury. Bouguereau, in particular, was renowned for his highly polished, idealized depictions of mythological figures, peasants, and especially nudes, executed with flawless technical precision. Robert-Fleury was also a respected history painter and portraitist, deeply embedded in the Salon system. Studying under these masters instilled in Chabas a profound respect for draftsmanship, anatomical accuracy, and the smooth, finished surfaces favored by the Academy.

This educational background placed Chabas firmly within the academic tradition, a style that emphasized classical ideals, historical or mythological subject matter, and a conservative approach to form and technique. This was the dominant force in French art for much of the 19th century, championed by the Académie des Beaux-Arts and showcased at the annual Paris Salon. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme and Alexandre Cabanel were exemplars of this tradition, achieving immense fame and official patronage through their mastery of academic principles. Chabas entered this world as Impressionism was becoming more accepted and Post-Impressionism was challenging artistic norms, yet he remained committed to the path laid out by his teachers.

Rising Through the Ranks: Success at the Paris Salon

The Paris Salon was the most important art exhibition in the world during the late 19th century. Acceptance into the Salon, and particularly winning an award there, was crucial for an artist's career, bringing critical attention, potential state purchases, and commissions. Chabas began exhibiting at the Salon relatively early in his career, making his debut possibly around 1890. He quickly gained recognition for his technical skill and appealing subject matter.

A significant breakthrough came in 1899 when his painting Joyeux Ébats (Happy Frolics or Playful Games) was exhibited at the Salon. This work, likely depicting nude or semi-nude figures in a joyful, natural setting, captured the attention of the jury and the public. It was awarded the prestigious Prix National, a major honor that solidified his reputation. The painting was later acquired by the Musée des Arts de Nantes, his hometown museum, signifying its importance.

His success continued. At the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) held in Paris in 1900, a global showcase of arts and industry, Chabas was awarded a gold medal. These accolades confirmed his status as a rising star within the established art world. He was successfully navigating the competitive Salon system, producing works that appealed to the prevailing tastes for idealized beauty, gentle sentiment, and technical proficiency, much like his teacher Bouguereau, though often with a greater emphasis on landscape and natural light. During this period, the Salon featured a diverse range of artists, from established academicians to Symbolists like his brother Maurice Chabas or Gustave Moreau, and even artists influenced by Impressionism, such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir, whose later works sometimes appeared there.

Artistic Style: The Idyllic Nude in Nature

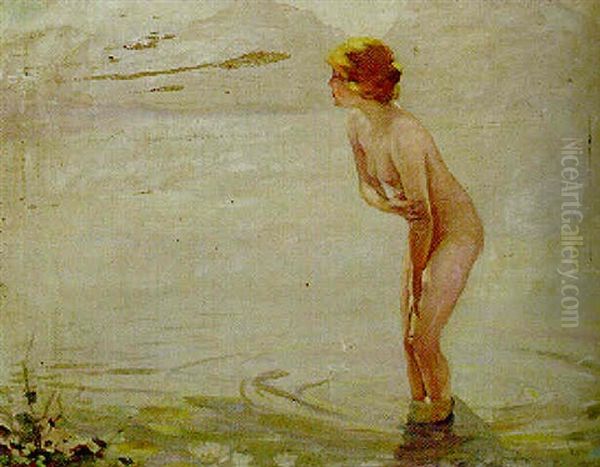

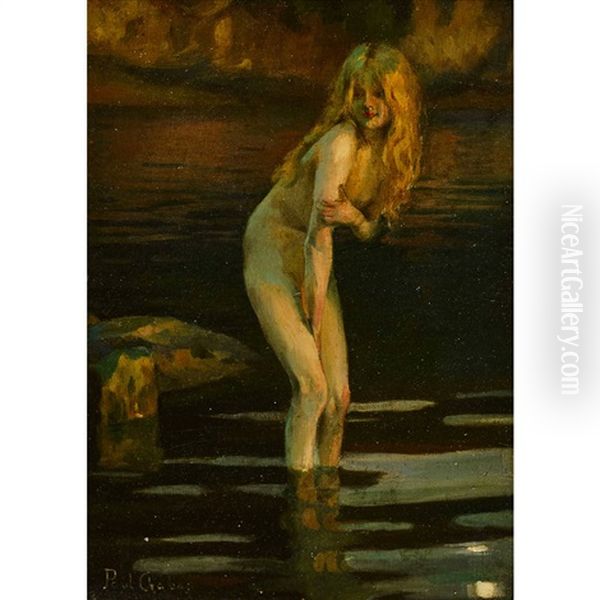

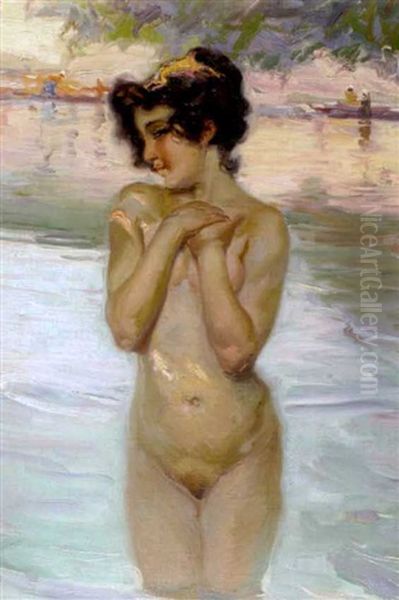

Paul Émile Chabas developed a distinct and recognizable style centered on the depiction of the female nude, typically adolescent or young adult women, placed within serene natural environments. His preferred settings were often riverbanks, lakesides, or coastal scenes, where the interplay of light, water, and flesh could be explored. Unlike the often dramatic or mythological contexts used by older academic painters, Chabas favored simple, everyday moments of bathing or repose, imbued with an air of innocence and tranquility.

His handling of light is a key characteristic. He often employed a soft, diffused illumination, particularly effective in rendering the subtle tones of skin and the shimmering reflections on water. This approach lent his paintings an ethereal, almost dreamlike quality. His color palette tended towards delicate pastels and harmonious tones, enhancing the sense of peace and gentle beauty. While his figures were based on academic principles of drawing and idealized form, his treatment of landscape and light sometimes showed a subtle awareness of Impressionistic concerns, particularly in the rendering of water and atmosphere, though without adopting their broken brushwork or focus on fleeting moments.

Some critics and historians have noted a potential influence from Scandinavian artists, such as Anders Zorn, who was also known for his depictions of nudes in outdoor settings and his masterful handling of light on water. There are also connections to be made with the aesthetics of Art Nouveau, particularly in the graceful lines and decorative quality of some of his compositions. However, Chabas remained fundamentally an academic painter, prioritizing smooth finish and idealized representation over modernist experimentation. His nudes are chaste and sentimental, lacking the overt sensuality or psychological depth found in the work of contemporaries exploring more challenging themes. He was considered one of Europe's notable painters of the nude, perfecting a specific vision of youthful innocence merged with nature.

Matinée de Septembre: Masterpiece or Scandal?

In 1912, Chabas exhibited a painting at the Paris Salon titled Matinée de Septembre (September Morn). The work depicts a young, completely nude woman standing ankle-deep in the calm, reflective waters of a lake, possibly Lake Annecy which he often visited. She modestly crosses her arms over her body, seemingly caught in a private moment, perhaps shivering slightly in the cool morning air. The light is soft, the colors are muted blues, greens, and pinks, and the overall mood is one of serene innocence. The painting was well-received at the Salon, earning Chabas the Medal of Honor for that year. It seemed destined to be another successful, if unremarkable, addition to his oeuvre of idyllic nudes.

However, the fate of September Morn took a dramatic and unexpected turn when a reproduction arrived in the United States the following year. In May 1913, a print of the painting was displayed in the window of Braun and Company, an art gallery on West 46th Street in New York City. This caught the attention of Anthony Comstock, the aging but still formidable head of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Comstock, a fervent moral crusader against anything he deemed obscene, was outraged by the public display of the nude figure.

Comstock famously stormed into the gallery demanding the removal of the "immoral" picture. The gallery owner refused, reportedly arguing it was a work of art. Comstock then took his complaint to the local authorities, initiating legal action against the dealer. The resulting publicity was immediate and explosive. Newspapers across the country picked up the story, splashing headlines about the "art vs. vice" battle. Comstock's condemnation, intended to suppress the image, ironically propelled September Morn to unprecedented fame.

The Controversy and Its Aftermath

The September Morn controversy became a national sensation in the United States. Anthony Comstock's actions inadvertently turned the painting into a symbol of the clash between conservative Victorian morality and emerging modern attitudes towards art and the human body. The court case against the art dealer ultimately failed; the judge did not find the painting legally obscene. However, the damage – or rather, the publicity – was done. The phrase "September Morn" entered the popular lexicon, often used humorously or ironically.

The controversy vastly increased public interest in the painting. Reproductions flew off the shelves. Enterprising promoters, allegedly including the notorious publicist Harry Reichenbach (though accounts vary), capitalized on the scandal, possibly even orchestrating parts of it to boost sales. The image appeared everywhere: on postcards, calendars, cigar boxes, candy tins, and even sheet music covers. It became one of the most widely recognized images in America, though often divorced from its original artistic context and appreciated more for its notoriety.

For Chabas, living in France, the American scandal was likely bewildering. He reportedly expressed surprise at the uproar, stating his artistic intentions were pure and innocent. While the controversy made him famous internationally, it also typecast him. Critics, particularly those embracing modernism, sometimes dismissed his work, including September Morn, as sentimental kitsch, technically proficient but lacking artistic depth or innovation. They argued that his style was repetitive and overly reliant on a formula of pretty, idealized nudes. The scandal cemented the painting's fame but perhaps detracted from a more nuanced appreciation of Chabas's skills as a painter within the academic tradition. The original painting was eventually acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1957, where it remains a popular, if somewhat notorious, exhibit. The incident recalls earlier art scandals, like the hostile reception to Édouard Manet's Olympia or Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe decades earlier, though the context and nature of the objections were different.

Other Notable Works and Thematic Consistency

While September Morn remains his most famous work due to the controversy, Paul Émile Chabas produced a considerable body of work throughout his career, much of it exploring similar themes and demonstrating his consistent style. His focus rarely strayed far from the idealized female form within natural settings, particularly associated with water.

Works like La baigneuse (The Bather) and Deux baigneuses (Two Bathers) continue the theme of women bathing, showcasing his skill in rendering flesh tones and the reflective qualities of water. Nymphe au bord de l'eau (Nymph at the Water's Edge, 1919) adds a subtle mythological element, though the treatment remains gentle and naturalistic rather than grandly historical. Paintings set specifically at Lake Annecy, such as Baigneuse au lac d'Annecy (Bather at Lake Annecy), highlight his connection to this location, which provided the likely backdrop for September Morn.

Other titles like Derniers rayons (Last Rays, c. 1896) and Sur l'eau (On the Water, c. 1896) suggest an interest in capturing specific effects of light at different times of day, hinting at a connection to plein air concerns, even if executed with academic finish. Repos dans l'arbre (Resting in the Tree) offers a slight variation on the setting but maintains the theme of youthful repose in nature. A work titled Au Crépuscule (At Dusk) gained an interesting afterlife when it was reportedly copied or acquired by the Lebanese painter Moustafa Farroukh, indicating Chabas's reach extended beyond Europe and North America.

These works, many now held in private collections and occasionally appearing at auction, reinforce the image of Chabas as a specialist. He found a successful formula and largely adhered to it, refining his technique in depicting the interplay of light, water, and the idealized female form. While perhaps lacking the thematic variety of some contemporaries, his dedication to this specific vision resulted in a cohesive and recognizable body of work.

Chabas in the Context of His Contemporaries

Paul Émile Chabas occupied a specific niche within the complex art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His training under Bouguereau and Robert-Fleury placed him squarely in the lineage of French Academic art. He shared this background with numerous successful Salon painters like Léon Bonnat and Carolus-Duran (teacher of John Singer Sargent), who also excelled in traditional techniques and enjoyed official recognition.

However, his career unfolded during a period of radical artistic innovation. The Impressionists (Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas) had already revolutionized painting decades earlier, and their influence was becoming more widespread. The Post-Impressionists (Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin) were pushing boundaries further in terms of form, color, and emotional expression. Symbolism, the movement his brother Maurice Chabas belonged to, explored dreams, myths, and subjective states, with artists like Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon offering alternatives to academic realism.

Shortly after Chabas achieved his initial Salon successes, new movements emerged that would define modern art: Fauvism, led by Henri Matisse, with its bold, non-naturalistic color; and Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, which fragmented form and revolutionized pictorial space. Compared to these avant-garde developments, Chabas's art remained conservative. He did not engage with the radical formal experiments or the challenging subject matter explored by many of his contemporaries.

His closest artistic kinship remained with the academic tradition and perhaps with artists who blended academic skill with slightly more modern sensibilities, like the aforementioned Anders Zorn in Sweden or certain aspects of Art Nouveau aesthetics. His connection to his brother Maurice provides a link to Symbolism, but Paul's own work generally lacks the overt mysticism or complex iconography typical of that movement. He remained a Salon painter, successful within that system but largely untouched by the major currents of modernism that were reshaping the art world around him.

Later Career, Legacy, and Market Presence

Following the unexpected international fame brought by September Morn, Paul Émile Chabas continued his career as a respected painter in France. He remained active, producing portraits and his signature scenes of bathers. His status within the French art establishment was confirmed by his election to the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1921, occupying the seat previously held by the historical painter Luc-Olivier Merson. He also became a member of the Légion d'honneur, further cementing his official recognition.

He continued to exhibit, though perhaps never again achieving the level of public notoriety – positive or negative – that September Morn had generated. He passed away in Paris on May 10, 1937, at the age of 68.

Chabas's legacy is somewhat complex. On one hand, he was a highly skilled painter within the academic tradition, capable of producing works of considerable charm and technical finesse. His handling of light and atmosphere, particularly in his water scenes, is often admired. On the other hand, his fame rests disproportionately on a single work whose reputation was largely built on scandal rather than purely artistic merit. This has led to him sometimes being overlooked or dismissed in broader surveys of art history that focus on modernist innovation.

His works continue to appear on the art market, finding buyers particularly among collectors interested in French academic painting or the specific theme of the female nude. Auctions at houses like Drouot in Paris or Fontainebleau, as well as international sales, regularly feature his paintings, often fetching respectable prices. Works reside in museum collections, notably the Musée d'Arts de Nantes (Joyeux Ébats) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (September Morn), ensuring his visibility. However, critical opinion remains divided, with some appreciating his gentle beauty and skill, while others find his work repetitive and overly sentimental, a relic of a bygone era overshadowed by the revolutionary changes in art that occurred during his lifetime.

Conclusion: An Artist Shaped by His Time and a Scandal

Paul Émile Chabas represents a particular strand of French art at the turn of the 20th century. He was a product of the rigorous academic system, mastering its techniques and achieving significant success within its framework, particularly at the Paris Salon. His specialization in depicting idealized young female nudes in tranquil natural settings brought him awards and recognition. He created a body of work characterized by technical skill, soft light, and a gentle, innocent sensuality.

Yet, his place in art history was irrevocably altered by the American controversy surrounding September Morn. This single incident propelled him to a level of international fame few academic painters achieve, but it also tied his name to notions of scandal, censorship, and popular kitsch. It overshadowed his other accomplishments and perhaps prevented a more balanced assessment of his artistic contributions.

Ultimately, Chabas remains a figure defined by this duality: a respected member of the French artistic establishment whose greatest fame came not from the accolades of the Salon, but from the moral outrage of a society grappling with changing representations of the human body. His story highlights the complex interplay between artistic creation, public reception, cultural values, and the often unpredictable path of an artist's reputation through history. He stands as a testament to a specific aesthetic moment and a curious footnote in the broader narrative of modern art's emergence.