Gino Rossi (1884-1947) stands as a pivotal yet often tragically overlooked figure in the landscape of early 20th-century Italian modernism. A painter and sculptor of considerable talent, Rossi's life and career were marked by an intense engagement with the burgeoning artistic innovations of his time, a profound connection to his Venetian roots, and a series of personal hardships that deeply colored his artistic output. His journey from a privileged upbringing to the forefront of Italian avant-garde circles, and his subsequent descent into personal struggle, offers a compelling narrative of an artist grappling with tradition, modernity, and the human condition. This exploration will delve into his origins, his transformative experiences, his evolving artistic style, key works, influential relationships, and his lasting, albeit sometimes muted, legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Venice and Florence

Born in Venice in 1884 into a prosperous family, Gino Rossi's early life provided him with a rich cultural and educational foundation. Venice, with its unique artistic heritage – the luminous colorism of Titian and Tintoretto, the grandeur of its Byzantine mosaics, and its constant interplay of light and water – undoubtedly seeped into his nascent artistic consciousness. This environment, steeped in centuries of artistic achievement, offered a powerful, if traditional, starting point.

His formal education took him to Florence, another cradle of the Italian Renaissance, where he attended the Foscari School. Florence would have exposed him to the masterpieces of Giotto, Masaccio, and Michelangelo, reinforcing a classical understanding of form and composition. However, Rossi was not destined to be a mere academician. Even in these early years, he demonstrated an interest that extended beyond the purely Italian tradition. He was drawn to the expressive power of artists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, whose works were beginning to challenge the established norms of European art. This burgeoning interest in transalpine modernism signaled the direction his artistic path would eventually take. The confluence of a deep-seated Italian humanism, the vibrant legacy of Venetian color, and an early curiosity for international artistic currents set the stage for Rossi's unique artistic synthesis.

The Parisian Crucible: Embracing Modernism

The year 1907 marked a critical turning point in Gino Rossi's artistic development: his journey to Paris. The French capital was then the undisputed epicenter of the avant-garde, a melting pot of revolutionary ideas and artistic experimentation. For a young artist like Rossi, Paris was a revelation. He immersed himself in the city's vibrant art scene, frequenting museums and galleries, and absorbing the radical new approaches to color, form, and subject matter.

It was in Paris that Rossi came into direct contact with the full force of Post-Impressionism and the nascent Fauvist and Cubist movements. The bold, non-naturalistic colors and emotional intensity of Fauvism, spearheaded by artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain, left a significant impression. Similarly, the structural innovations of Paul Cézanne, who sought to "treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone," and the early Cubist explorations of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, challenged traditional notions of perspective and representation. Rossi was particularly captivated by the work of Paul Gauguin, whose Tahitian paintings, with their flat planes of color, simplified forms, and "primitive" spirituality, resonated deeply with him. He also encountered fellow Italian artists in Paris, such as Amedeo Modigliani and his close friend, the sculptor Arturo Martini, fostering a sense of shared purpose among expatriate Italian modernists. This period also saw him explore the landscapes of Northern Europe and the Netherlands, further broadening his visual vocabulary.

Return to Italy and the Ca' Pesaro Years

Upon his return to Italy, armed with the transformative experiences of Paris, Gino Rossi became an active participant in the burgeoning Italian modern art scene. He found a spiritual home in the exhibitions at Ca' Pesaro, the International Gallery of Modern Art in Venice. This institution, under the enlightened guidance of Nino Barbantini, became a crucial platform for young, rebellious artists who sought to break free from the academicism that still dominated much of the Italian art world. Rossi exhibited regularly at Ca' Pesaro, starting around 1910, alongside other progressive artists.

His works from this period, roughly between 1910 and 1913, clearly show the impact of his Parisian sojourn. There's a distinct Fauvist sensibility in his use of vibrant, often unmodulated color, and a Gauguinesque lightness and ethereal quality to some of his compositions. He was part of a dynamic group of artists associated with Ca' Pesaro, including his friend Arturo Martini, as well as painters like Pio Semeghini, Felice Casorati, Umberto Moggioli, and Tullio Garbari. These artists, while diverse in their individual styles, shared a common desire to revitalize Italian art by engaging with international modernism while often retaining a connection to their Italian heritage. Rossi's participation in exhibitions such as the Esposizione Cispadana in Venice and the Esposizione Internazionale Femminile di Torino in Turin further solidified his reputation as a significant voice in this new wave of Italian art. The 1912 Salon d'Automne in Paris, where he exhibited, also marked an important international recognition.

Artistic Style and Evolution: A Synthesis of Influences

Gino Rossi's artistic style was not static; it was a dynamic evolution, a testament to his restless intellect and his continuous search for expressive means. His early works, while showing academic grounding, quickly gave way to a more modern sensibility. The influence of French Post-Impressionism, particularly the aforementioned Gauguin and Van Gogh, is evident in his approach to color and emotional content.

The period following his Parisian stay (circa 1907-1914) is often characterized by a vibrant palette and a simplification of forms, aligning with Fauvist principles. He explored the expressive potential of color, using it not merely for description but to convey emotion and structure the composition, much like Matisse. There's also a decorative quality and a search for a certain "primitive" directness that echoes Gauguin.

Later, particularly after his experiences in World War I and his exposure to further developments in European art, Rossi's style shifted. The influence of Paul Cézanne became more pronounced. This manifested in a greater emphasis on underlying geometric structure, a more constructed sense of form, and a focus on the "vibration" of color and the reinforcement of shapes. He paid close attention to the framing of his compositions and the interplay of curves and planes. This Cézannian phase led him towards a more analytical, almost Cubist-inflected approach in some works, where objects and figures are broken down into faceted planes, though he never fully embraced the analytical rigor of Picasso or Braque. Instead, his Cubism was often tempered by a lingering lyricism and a concern for emotional expression.

Throughout his career, Rossi demonstrated a remarkable ability to synthesize diverse influences – from the colorism of the Venetian tradition and the formal concerns of Cézanne to the expressive freedom of Fauvism and the exoticism of Gauguin. He also showed an interest in the work of sculptors like Alexander Archipenko, whose fragmented forms may have informed his own explorations of volume and space on canvas. His later works sometimes tended towards a more subdued, even monochromatic palette, and a rougher, more textural application of paint, reflecting perhaps both his internal struggles and a move towards a more starkly expressive modernism.

Key Works and Thematic Concerns

Gino Rossi's oeuvre, though tragically curtailed, includes several works that encapsulate his artistic vision and stylistic development. Among his most celebrated pieces is La fanciulla del fiore (The Flower Girl), also sometimes referred to as Fanciulla del Mare (Girl of the Sea), exhibited at the 1912 Salon d'Automne. This painting, with its vibrant colors and simplified forms, is often considered one of his early masterpieces, embodying the poetic synthesis of Fauvist and Gauguinesque influences.

Works like Maternità (Maternity) and L'educazione (The Education) delve into intimate, human themes. Maternità, in particular, is a recurring subject, reflecting perhaps his own complex feelings about family and human connection, especially in light of his wife's later illness. These pieces often convey a tender yet unsentimental monumentality. Ritratto di signora (Portrait of a Lady) showcases his ability to capture psychological depth within a modernist framework.

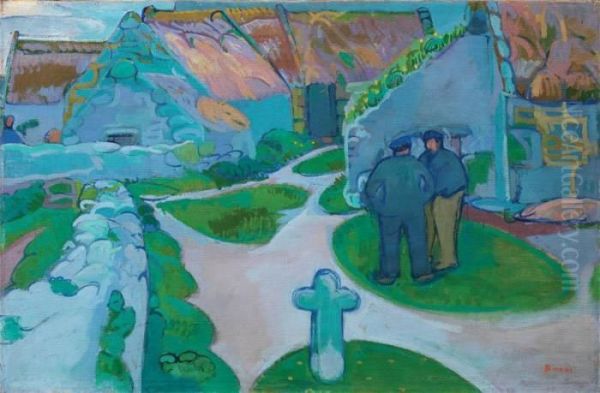

His engagement with landscape and everyday life is evident in paintings such as Asolo descrizione (Description of Asolo), Pescatori (Fishermen), and Canale in Bretagna (Canal in Brittany). These works demonstrate his ability to transform ordinary scenes into compelling artistic statements through his distinctive use of color and form. Asolo descrizione and other depictions of the Veneto region reveal his deep connection to his native landscape, while his Breton scenes, inspired by his travels, show an affinity for the rugged beauty and distinct cultural identity of Brittany, much like Gauguin and Émile Bernard before him.

The painting Bruto (Brutus), likely a depiction of a common man, highlights Rossi's interest in portraying figures from the lower classes with a powerful, almost raw expressiveness. This concern for the "humble" subject connects him to a broader humanist tradition in art. Still lifes, such as Natura morta con brocca (Still Life with Jug), provided a vehicle for formal experimentation, allowing him to explore the Cézannian principles of structure and color modulation. His works often sought a balance between abstraction and decoration, exploring the inherent musicality of line and color.

Collaborations and Contemporaries: A Network of Modernists

Gino Rossi was not an isolated figure; he was part of a vibrant network of artists who were collectively shaping the future of Italian art. His most significant artistic relationship was undoubtedly with the sculptor Arturo Martini. They were close friends and shared a studio for a time. Their artistic dialogue was fruitful, with shared thematic interests, such as the mother figure and an occasional nod to "Chinoiserie" or Far Eastern artistic elements. Both were central figures in the Ca' Pesaro group, championing the cause of young, innovative artists.

Beyond Martini, Rossi was connected with other key figures of the Ca' Pesaro circle and the broader Italian modernist movement. Pio Semeghini, with his lyrical landscapes, and Felice Casorati, known for his enigmatic, precisely rendered figures, were important contemporaries. While their styles differed, they shared a commitment to moving Italian art beyond 19th-century conventions. Rossi's work also shows an awareness of, if not direct collaboration with, the broader currents of Italian art, including the lingering influence of Divisionism (as seen in the work of Giacomo Balla before his Futurist phase) and the atmospheric landscapes of artists like Umberto Moggioli.

His Parisian experiences brought him into the orbit of international modernism. While direct collaborations with figures like Matisse, Picasso, or Gauguin are not documented, their influence was profound and pervasive. He absorbed lessons from Cézanne's structural approach, the Fauves' chromatic freedom, and the early Cubists' deconstruction of form. He would have also been aware of other Italian artists making their mark in Paris, such as Amedeo Modigliani, Gino Severini (who became a leading Futurist), and Ardengo Soffici, a critic and painter who played a key role in disseminating French avant-garde ideas in Italy. The dynamic artistic environment of early 20th-century Europe, with its rapid succession of movements – from Post-Impressionism through Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism (though Rossi was not a Futurist like Boccioni or Carrà) – provided a rich and challenging context for his work.

Personal Trials, War, and Later Years

Gino Rossi's promising career was tragically impacted by profound personal difficulties and the trauma of war. The outbreak of World War I was a devastating interruption. Like many artists of his generation, he was called to serve. The horrors of the conflict left deep psychological scars, contributing to a period of intense mental distress. This led to his confinement in the Sant'Artemio psychiatric hospital in Treviso.

His personal life was also marked by sorrow. His wife, Giovanna Bieleto, suffered a mental breakdown and eventually passed away, a loss that undoubtedly exacerbated Rossi's own fragile mental state. These experiences cast a long shadow over his later life and art. While he continued to create, his output became more sporadic, and his connection to the mainstream art world perhaps more tenuous.

In his later years, Rossi lived in relative seclusion in Treviso. Despite his withdrawal, he continued to paint, his work often imbued with a poignant intensity and a sense of profound introspection. The vibrant colors of his earlier Fauvist-inspired period often gave way to more somber tones, and his forms sometimes took on a more rugged, almost tormented quality. This period reflects an artist grappling with inner demons and the weight of a life marked by both brilliant artistic insight and deep personal suffering. He passed away in 1947, his full potential perhaps unrealized due to the cruel intersection of historical events and personal tragedy.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Despite the brevity of his most productive period and the challenges he faced, Gino Rossi's contribution to Italian modern art is undeniable. He was a crucial bridge figure, one of the first Italian artists of his generation to fully assimilate the lessons of French Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and early Cubism, and to translate these international idioms into a distinctly Italian context. His work at Ca' Pesaro helped to foster an environment of artistic innovation in Venice, challenging the prevailing academicism.

Rossi is recognized as a pioneer of what might be termed Italian Neo-Impressionism (in its broadest sense of engaging with Post-Impressionist color theory) and an early adopter of Cubist principles in Italy. His ability to synthesize diverse influences – the Venetian color tradition, Cézanne's structure, Gauguin's symbolism, and Matisse's expressive color – resulted in a body of work that is both historically significant and aesthetically compelling. His art has been described with terms like "madness," "genius," and "solitude," reflecting the intense, often tortured, expressiveness that characterized his best work.

Posthumously, his work gained renewed attention. A significant retrospective at the Venice Biennale in 1948, shortly after his death, helped to re-evaluate his contribution. Exhibitions of his work, such as those featuring Paese in Bretagna in 1949 and 1956, continued to affirm his importance. While perhaps not as widely known internationally as some of his contemporaries like Modigliani or the Futurists, Gino Rossi remains a key figure for understanding the development of modern art in Italy. His legacy lies in his courageous embrace of modernism, his lyrical and expressive power, and his poignant testament to the enduring human spirit in the face of adversity. He remains an artist whose work continues to resonate with its emotional depth and innovative vision.