Gioacchino Toma (1836-1891) stands as one of the most compelling and poignant artistic figures of nineteenth-century Italy. An Italian national, born in Galatina in the Lecce province of Apulia (then part of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies), his life and art were predominantly centered in Naples. His work, deeply imbued with personal experience and a keen observation of the human condition, offers a unique window into the social, political, and emotional currents of his time. While often associated with the Neapolitan School of painting, Toma carved out a distinct path, blending elements of Realism with a profound Romantic sensibility, often tinged with melancholy and a quiet, introspective symbolism. His legacy is that of an artist who not only mastered his craft but also used it to give voice to the marginalized and to explore the depths of human feeling.

A Childhood Forged in Hardship

Toma's early life was marked by profound loss and instability, experiences that would indelibly shape his artistic vision. Born on January 24, 1836, he was orphaned at a young age. His father, a doctor from a respected local family, passed away when Gioacchino was still a child, followed shortly by his mother. This tragic turn of events led to a childhood spent in various institutions, including the hospice for the poor in Giovinazzo and later, a convent. These formative years in orphanages and under the care of religious orders exposed him to the realities of poverty, displacement, and the lives of those on the fringes of society. Such experiences undoubtedly fostered in him a deep empathy that would later manifest powerfully in his paintings, particularly in his depictions of children and the dispossessed.

His early education was rudimentary, but it was within these institutional settings that he likely received his first exposure to art, perhaps through religious imagery or decorative crafts. The discipline and solitude of these environments may have also contributed to his introspective nature, a quality that permeates much of his later work. The emotional weight of this period, the sense of being an outsider, and the longing for familial warmth became recurring, if often subtle, undercurrents in his artistic output.

Neapolitan Awakening: Artistic Formation and Influences

Around 1854-1855, seeking a different path, Toma made the pivotal decision to move to Naples. This bustling metropolis, a vibrant cultural hub with a rich artistic heritage, was to become his adopted home and the primary stage for his artistic career. Initially, he pursued decorative painting to support himself, a common entry point for aspiring artists of the era. However, his ambition lay in fine art, and he soon enrolled, albeit somewhat intermittently, at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Naples (Reale Accademia di Belle Arti di Napoli).

At the Academy, and within the broader Neapolitan art scene, Toma encountered several influential figures. Perhaps the most significant among his mentors was Domenico Morelli (1823-1901), a leading figure in Neapolitan painting who was himself transitioning from Romanticism towards a more historical and realistic approach, often infused with dramatic flair. Morelli's guidance and his emphasis on verisimilitude and emotional expression would have resonated with Toma.

Toma also absorbed influences from the School of Posillipo, a landscape painting tradition that flourished in Naples, known for its plein-air approach and its luminous depictions of the Bay of Naples and its surroundings. Key figures associated with this school, such as its Dutch founder Anton Sminck van Pitloo (1790-1837) and his successor Giacinto Gigante (1806-1876), had already established a strong tradition of capturing natural light and atmosphere. While Toma was not primarily a landscape painter in the Posillipo vein, their sensitivity to light and environment can be seen in the atmospheric qualities of his interiors and outdoor scenes. He was also connected with later proponents or artists influenced by this tradition, such as Antonio Pitrucci and Filippo Paccini, who continued to explore light and landscape.

The Neapolitan art world of the mid-nineteenth century was a dynamic environment. Artists like Filippo Palizzi (1818-1899), known for his meticulous realism, especially in animal paintings and rural scenes, and his brother Giuseppe Palizzi (1812-1888), who found success in Paris, were important contemporaries. The move towards Realism was a broader European phenomenon, and in Naples, it took on a particular character, often focusing on local life, social issues, and historical narratives relevant to the region.

Political Turmoil and Personal Development

Toma's artistic development was briefly interrupted by political events. He was a fervent patriot and supported the cause of Italian unification (the Risorgimento). In 1857, he was unjustly suspected of anti-Bourbon conspiracy and was briefly imprisoned before being exiled to Piedimonte d'Alife (now Piedimonte Matese). During this period of confinement and exile, he continued to paint, producing portraits for local families and religious works. This experience, while challenging, likely deepened his resolve and perhaps sharpened his critical perspective on authority and injustice.

With the fall of the Bourbon monarchy and Garibaldi's entry into Naples in 1860, Toma joined the Garibaldian forces, serving as a volunteer. These experiences of political engagement and conflict further broadened his understanding of the societal shifts occurring around him. Upon returning to Naples after the unification, he dedicated himself more fully to his art, his style gradually maturing. He also began to teach, eventually becoming a professor of design at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Naples, a position that provided him with some financial stability and allowed him to influence a new generation of artists, including Vincenzo Irolli (1860-1949), known for his vibrant depictions of Neapolitan life.

Thematic Concerns: Orphans, Prisoners, and the Quiet Dramas of Life

Toma's oeuvre is characterized by a profound engagement with themes of human suffering, resilience, and the quiet dramas of everyday life. His personal history as an orphan deeply informed his frequent depictions of children, particularly those in vulnerable situations. These are not sentimentalized portrayals but rather empathetic studies of innocence and hardship.

Works like La Ruota dei Trovatelli (The Foundling Wheel) and Il Viatico dell'Orfana (The Viaticum of the Orphan, 1877), the latter housed in the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea (GNAM) in Rome, are exemplary. Il Viatico dell'Orfana portrays a young orphan girl receiving her first communion, a moment of spiritual significance set against a backdrop of austere simplicity. The painting is suffused with a palpable sense of melancholy and introspection, the girl's solemn expression and the muted color palette conveying a complex emotional state. The "foundling wheel" itself was a device in orphanages where infants could be anonymously abandoned, a stark symbol of societal desperation that Toma addressed with sensitivity.

Another powerful and iconic work is Luisa Sanfelice in Carcere (Luisa Sanfelice in Prison, 1874, also at GNAM, Rome). This painting depicts Luisa Sanfelice, a Neapolitan noblewoman executed in 1799 for her involvement in the Parthenopean Republic. Toma portrays her not in a moment of heroic defiance, but in quiet contemplation in her prison cell, awaiting her fate. The sparse setting, the play of light and shadow, and Sanfelice's resigned yet dignified posture create an image of immense emotional power. It speaks to themes of political martyrdom, the cruelty of power, and individual suffering in the face of historical forces. This work cemented his reputation as an artist capable of profound historical and psychological insight.

Toma also explored domestic interiors, scenes of convent life, and moments of quiet labor. Un Romanzo al Convento (A Novel at the Convent) captures a nun engrossed in a book, a simple scene that hints at an inner life and perhaps a longing for the world beyond the cloister walls. His still lifes, though less numerous, demonstrate his skill in composition and his ability to imbue ordinary objects with a sense of presence and quiet dignity.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Realism, Romanticism, and Symbolism

Gioacchino Toma's style is a distinctive fusion. While rooted in the Realist tradition's commitment to depicting the world truthfully, his work transcends mere reportage. It is imbued with a Romantic sensibility, evident in its emotional depth, its focus on individual experience, and its often melancholic or nostalgic mood.

His compositions are carefully constructed, often characterized by a sense of order and stillness. He favored a muted, often cool, color palette, using subtle gradations of tone to create atmosphere and model form. Light plays a crucial role in his paintings, not merely to illuminate but to create mood and highlight psychological states. It often filters softly into interiors, creating a sense of intimacy or confinement, as seen in Luisa Sanfelice in Carcere or his depictions of convent life.

There is a strong element of symbolism in Toma's work, though it is rarely overt or didactic. Objects, gestures, and settings often carry deeper meanings, hinting at unspoken emotions or broader social commentaries. The very sparseness of some of his interiors can symbolize emotional desolation or the constraints of poverty. His figures are often introspective, their gazes averted or directed inward, suggesting a rich inner life that the viewer is invited to contemplate.

A significant work that marked a development in his style and thematic concerns was Un Esame Rigoroso del Sant'Uffizio (A Rigorous Examination by the Holy Office, 1864), sometimes referred to as Galileo in Prison or The Interrogation. This painting, depicting a scene of intellectual persecution, was criticized by some at the time but demonstrated his willingness to tackle challenging historical subjects with psychological depth. It signaled a move towards more complex narratives and a greater emphasis on the emotional and psychological dimensions of his subjects.

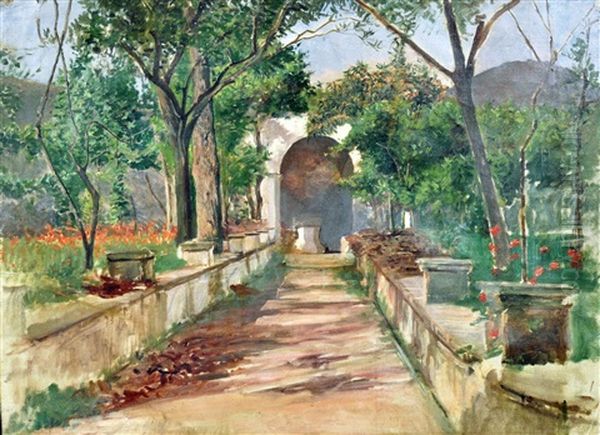

His landscape paintings, such as Villa a Torre del Greco (likely painted in the 1870s or 1880s and housed in a Naples museum) or La Pioggia (Rain), showcase his ability to capture specific atmospheric conditions and the character of the Neapolitan environs. These works often feature architectural elements integrated into the natural setting, reflecting his interest in the interplay between human presence and the environment. His visits to places like San Giovanni Teduccio and Torre del Greco in the 1870s yielded several such landscapes, often characterized by their evocative light and subtle melancholy.

Contemporaries and the Neapolitan Art Scene

Toma operated within a vibrant and evolving Neapolitan art world. Beyond his teacher Domenico Morelli, he was a contemporary of several other notable artists. Francesco Saverio Altamura (1822-1897) was another significant figure, known for his historical paintings and his involvement in the Risorgimento. Michele Cammarano (1835-1920) was celebrated for his battle scenes and genre paintings, often depicting scenes of contemporary Italian life and military events with a robust realism.

The younger generation included artists like Giuseppe De Nittis (1846-1884), who, though Neapolitan by birth and early training, achieved international fame in Paris with his elegant depictions of modern urban life, aligning him more with Impressionism. Antonio Mancini (1852-1930), known for his highly textured and psychologically intense portraits, was another prominent Neapolitan artist whose work, while different in technique, shared a certain emotional depth with Toma's.

While Toma's style was distinct, he participated in the broader artistic discourse of his time. He exhibited regularly, including at the exhibitions of the Società Promotrice di Belle Arti in Naples, showcasing works like La Fanciulla del Popolo (The Girl of the People) and Il Dono del Tributo di San Pietro (The Gift of Saint Peter's Pence). His engagement with the Posillipo School, even if indirect, connected him to a lineage that included artists like Consalvo Carelli (1818-1900) and Gabriele Smargiassi (1798-1882), who continued the tradition of Neapolitan landscape painting.

The broader Italian art scene also saw the rise of movements like the Macchiaioli in Tuscany, with artists such as Giovanni Fattori (1825-1908) and Telemaco Signorini (1835-1901), who were also exploring Realism and plein-air painting, though with a different stylistic emphasis on "macchia" (patches of color). While distinct, these parallel developments underscore the widespread shift towards realism and a focus on contemporary life and national identity in post-unification Italy.

Social Commentary and Political Undertones

Toma's art was rarely overtly political in the manner of propaganda, but it was deeply engaged with the social realities and, at times, the political undercurrents of his era. His depictions of orphans were a direct commentary on a significant social problem in Naples and other parts of Italy. The "ruota dei trovatelli" was a stark symbol of this issue, and Toma's paintings brought a human face to the statistics.

His historical paintings, like Luisa Sanfelice in Carcere, while set in the past, resonated with contemporary concerns about justice, political oppression, and individual sacrifice for a cause. The Risorgimento was still a recent memory, and themes of patriotism and the struggle for freedom were potent. Toma's own involvement with Garibaldi's forces indicates his personal commitment to these ideals.

Even in his less overtly narrative works, there is often a subtle critique of social conditions. The austerity of his settings, the worn clothing of his figures, and their often somber expressions speak to the hardships faced by many in nineteenth-century Italy. He gave dignity to the poor and the marginalized, portraying them not as objects of pity but as individuals with complex inner lives. His work Il Tatuaggio dei Camorristi (The Tattooing of the Camorrists) delved into the shadowy world of organized crime, another facet of Neapolitan social reality.

Teaching and Lasting Influence

From 1878, Gioacchino Toma held the position of professor of ornamental design at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Naples, and later, from 1882, he taught drawing there. His role as an educator allowed him to pass on his skills and artistic philosophy to a new generation. Among his students, Vincenzo Irolli became a notable painter, known for his vibrant and often joyful depictions of Neapolitan street life, a contrast to Toma's more somber tones but sharing a focus on local character. Another artist who benefited from his teaching was Lionello Balestrieri (1872-1958), though Balestrieri would later move towards Symbolism and Divisionism.

Toma's influence extended beyond his direct pupils. His commitment to realism, combined with his psychological depth and social conscience, resonated with the broader current of Verismo (Realism) in Italian art and literature. Artists who continued to explore social themes in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such as Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo (1868-1907), famous for Il Quarto Stato (The Fourth Estate), shared Toma's concern for the lives of ordinary people and the desire to use art as a means of social reflection, even if their styles evolved in different directions, such as Divisionism.

While perhaps not achieving the same international fame during his lifetime as some of his contemporaries like De Nittis, Toma's reputation has grown steadily. He is now recognized as a pivotal figure in nineteenth-century Italian art, particularly for his unique ability to blend meticulous observation with profound emotional resonance. His works are prized in major Italian museums, and he is seen as an artist who captured the soul of Naples and the spirit of his age with honesty and compassion.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Gioacchino Toma continued to paint and teach in Naples until his death on January 12, 1891. His later works maintained the introspective quality and technical refinement that characterized his mature style. He also authored an autobiography, Ricordi di un Orfano (Memories of an Orphan), published posthumously, which provides invaluable insights into his life, his thoughts on art, and the experiences that shaped him. This text underscores the deep connection between his personal journey and his artistic output.

His legacy is multifaceted. He was a master technician, capable of rendering form, light, and texture with great skill. He was a profound psychologist, able to convey complex emotions through subtle expressions and gestures. He was a social commentator, using his art to draw attention to the plight of the vulnerable and the injustices of his time. And he was a Neapolitan artist through and through, capturing the unique atmosphere and character of his adopted city.

Today, Gioacchino Toma is celebrated for his authenticity and his unwavering commitment to his artistic vision. His paintings offer more than just historical documents or aesthetic objects; they are deeply human testaments to the struggles, sorrows, and quiet dignities of life. In an era of grand historical narratives and burgeoning modernism, Toma's quiet, introspective art provides a powerful and enduring voice. His ability to find the universal in the particular, and to imbue scenes of ordinary life with profound meaning, secures his place as one of Italy's most significant nineteenth-century painters. His work continues to resonate with viewers for its technical brilliance, its emotional honesty, and its timeless exploration of the human condition.