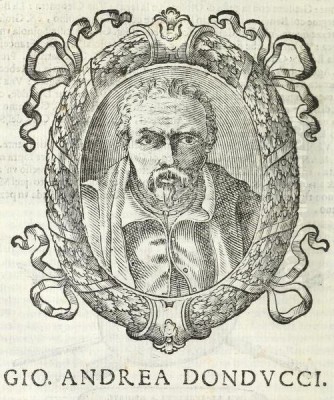

Giovanni Andrea Donducci, more famously known by his moniker "il Mastelletta," stands as a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure within the vibrant artistic milieu of early seventeenth-century Bologna. Born in this Emilia-Romagnan city in 1575, his life and career unfolded during a period of profound artistic transformation, largely instigated by the Carracci reform. Donducci, who passed away in 1655, carved out a distinctive niche for himself, characterized by an expressive, often unconventional approach to painting, particularly in his evocative landscapes that shimmered with a unique understanding of light and atmosphere. While he initially trained within the influential Carracci circle, his artistic temperament soon led him down a more personal and idiosyncratic path, resulting in a body of work that continues to intrigue scholars and art lovers alike for its originality and its departure from prevailing classical norms.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Bologna

Giovanni Andrea Donducci's early years were rooted in Bologna, a city then buzzing with artistic innovation. His nickname, "il Mastelletta," meaning "the little pail" or "small vat," is widely believed to derive from his father's profession as a cooper or barrel-maker. This humble origin story adds a layer of interest to his artistic journey, suggesting a path perhaps less conventional than that of artists from more established artistic dynasties.

The most significant formative influence on the young Donducci was undoubtedly his apprenticeship at the Accademia degli Incamminati (Academy of the Progressives, or Academy of Those on the Right Path). Founded around 1582 by Ludovico Carracci and his cousins, Annibale Carracci and Agostino Carracci, this academy was a crucible for a new direction in Italian art. The Carracci sought to move away from the perceived artificiality of late Mannerism, advocating a return to the study of nature, High Renaissance masters like Raphael and Titian, and a more direct, emotionally resonant form of expression. Within this environment, Donducci would have been exposed to rigorous training in drawing from life, anatomy, and perspective, alongside the study of classical and Renaissance exemplars. Ludovico Carracci, who remained in Bologna while Annibale and Agostino eventually moved to Rome, is often cited as his primary teacher and a significant early influence.

The Development of an Independent Style

Despite his grounding in the Carracci principles, which emphasized clarity, naturalism, and a certain classical poise, Donducci did not simply become a faithful follower. He absorbed the lessons of the academy but soon began to forge a style that was distinctly his own. This independent streak manifested in a painterly approach characterized by rapid, spirited brushwork, a dramatic use of chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark), and a penchant for dynamic, often agitated compositions. His handling of paint could be described as almost pre-impressionistic in its freedom, prioritizing expressive effect over meticulous finish.

This departure from the more polished classicism pursued by some of his Carracci-trained contemporaries, such as Guido Reni or Domenichino, marked Donducci as an original. His style was perceived by some, even in his own time, as somewhat "anti-traditional" or experimental. He was less concerned with idealized human beauty, a cornerstone for many of his peers, and more interested in conveying mood, atmosphere, and a sense of untamed nature. This is particularly evident in his landscapes, which became a significant part of his oeuvre. His figures, while often imbued with a certain rustic charm or dramatic intensity, sometimes lacked the anatomical precision or graceful design favored by the more classically inclined painters of the Bolognese School.

The Lure of the Landscape: Influences and Innovations

Donducci's most distinctive contributions lie in the realm of landscape painting. While the Carracci themselves, particularly Annibale, had elevated landscape painting with works like the Aldobrandini lunettes, Donducci pushed the genre in a more personal and atmospheric direction. His landscapes are rarely serene or idealized in the classical sense. Instead, they are often imbued with a sense of mystery, dynamism, and even a touch of wildness. Small, often biblical or mythological figures are frequently dwarfed by turbulent skies, gnarled trees, and rugged terrain, emphasizing the power and grandeur of nature.

His approach to landscape was informed by several sources. The influence of Ferrarese painters, such as Dosso Dossi from an earlier generation, and perhaps more contemporary figures like Scarsellino (Ippolito Scarsella), is discernible in the rich, often fantastical atmospheric effects and the poetic integration of figures within the natural setting. Ferrarese art had a long tradition of imaginative and evocative landscape. Furthermore, Donducci was receptive to the developments in landscape painting brought by Northern European artists active in Italy. Painters like Paul Bril and Adam Elsheimer, both of whom worked in Rome, were pioneers in creating more naturalistic and atmospheric landscapes, often on a small scale and with meticulous attention to light. Donducci seems to have absorbed their feeling for light and mood, translating it into his own more vigorous and painterly idiom. His landscapes are not mere backdrops but active participants in the narrative, often setting a powerful emotional tone.

Major Works and Commissions

Throughout his career, Donducci produced a significant body of work, including altarpieces, mythological scenes, and, most notably, landscapes with figures. One of his most celebrated works is The Mystical Marriage of St. Catherine. This painting showcases his ability to blend the religious fervor characteristic of the Bolognese school with his distinctive stylistic traits. While the subject is traditional, Donducci's treatment, with its dynamic composition and expressive figures, bears his unique stamp, likely reflecting the influence of Ludovico Carracci's more emotive style.

Another key work often cited is The Crossing of the Red Sea. This subject provided ample opportunity for Donducci to display his talent for dramatic narrative and atmospheric landscape. The swirling waters, the dramatic gestures of the figures, and the turbulent sky would have allowed his energetic brushwork and strong chiaroscuro to come to the fore, creating a scene of epic power and divine intervention. Similarly, his St. Margaret in the Desert (sometimes referred to as The Penitent Magdalene in the Desert) is a powerful example of his ability to convey intense emotion through both the figure and the surrounding landscape, the desolate wilderness echoing the saint's spiritual state.

Donducci also undertook significant public commissions. Between 1613 and 1614, he contributed to the decoration of the prestigious Arca di San Domenico (Chapel of Saint Dominic) in the Basilica of San Domenico in Bologna. This commission, which involved other prominent Bolognese artists such as Alessandro Tiarini and Lionello Spada, underscores his standing within the local artistic community. His frescoes for the chapel would have demonstrated his capacity to work on a larger scale and within a significant religious context, adapting his style to the demands of monumental decoration. The Assumption of the Virgin is another religious work that is considered a significant part of his output, showcasing his engagement with grand Marian themes.

Travels and Artistic Circles

While Bologna remained his primary base of operations, Donducci is known to have spent time in other major Italian artistic centers, notably Rome and Venice. These sojourns, though perhaps brief, would have exposed him to a wider range of artistic currents. In Rome, he would have encountered the revolutionary naturalism of Caravaggio and his followers, as well as the burgeoning classical landscape tradition being forged by artists like Annibale Carracci (by then established in Rome) and the aforementioned Northern painters. The vibrant artistic scene in Rome, with its rich patronage and diverse influences, likely further stimulated his experimental tendencies.

His time in Venice, the city of Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese, would have offered a different set of inspirations. Venetian painting, with its emphasis on color, light, and painterly brushwork, had long been a touchstone for artists seeking a more sensuous and atmospheric approach. Donducci's own predilection for rich textures and dramatic lighting effects may have found resonance in the Venetian tradition.

Back in Bologna, he was part of a thriving artistic community. Besides his initial connection to the Carracci, he would have interacted with other leading figures of the Bolognese School. Artists like Guido Reni, Domenichino, Francesco Albani, and Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) were his contemporaries, though their artistic paths often diverged significantly from his. While Reni and Domenichino pursued a more idealized classicism, Guercino, with his powerful chiaroscuro and dynamic compositions, shared some affinities with Donducci's more dramatic inclinations, albeit with a greater emphasis on monumental figural painting. Alessandro Tiarini, with whom he collaborated on the San Domenico project, was another important Bolognese painter of the period.

Artistic Strengths, Perceived Weaknesses, and Anecdotes

Art historical accounts, including those by early biographers like Carlo Cesare Malvasia in his "Felsina Pittrice" (1678), provide a nuanced picture of Donducci's talents. Malvasia, a key chronicler of Bolognese art, acknowledged Donducci's originality, particularly in landscape, but also pointed out perceived weaknesses. One recurring critique was his handling of the nude figure, which was sometimes considered less accomplished in terms of anatomical accuracy and idealized form compared to the standards set by the Carracci and their more classical followers.

However, Donducci often ingeniously compensated for any deficiencies in draughtsmanship through his masterful manipulation of light and shadow. His dramatic chiaroscuro could obscure anatomical details while heightening the emotional impact of his scenes. His figures, even if not perfectly rendered according to academic ideals, possessed a raw energy and expressiveness that contributed to the overall power of his compositions. His strength lay in his ability to create a compelling overall effect, a unified mood, rather than in the meticulous perfection of individual parts.

A charming anecdote, also recounted by Malvasia, sheds light on his personality and perhaps his sensitivity to his surroundings. It is said that while seeking tranquility for his work in the countryside near Sasso Marconi, Donducci found himself disturbed by the incessant playing of bagpipes by local shepherds. Unable to bear the sound, he eventually resorted to buying all their bagpipes to ensure silence. This story, whether entirely factual or embellished, paints a picture of an artist deeply attuned to his environment and perhaps somewhat eccentric.

His works found favor not only with ecclesiastical patrons but also with private collectors, including noble families in Rome, who appreciated the unique character of his paintings, especially his imaginative landscapes. This suggests a market for art that deviated from the purely classical, one that valued originality and expressive power.

Later Career, Death, and Legacy

Donducci continued to paint actively throughout the first half of the seventeenth century, leaving behind a considerable body of work. He died in Bologna in 1655, having witnessed significant shifts in artistic taste and practice. While he may not have achieved the same level of international fame as some of his Bolognese contemporaries like Reni or Guercino, his contribution to the art of his time is undeniable.

His legacy lies in his distinctive artistic voice and his contribution to the development of landscape painting. He demonstrated that the lessons of the Carracci could lead to diverse artistic outcomes, and his work stands as a testament to the creative possibilities that lay beyond the more rigidly defined classical path. His expressive brushwork and his focus on atmospheric effects in landscape can be seen as anticipating certain aspects of later landscape traditions.

In the broader context of Italian Baroque art, Donducci occupies a unique position. He was not a revolutionary figure in the mold of Caravaggio, nor a defining master of High Baroque classicism like Annibale Carracci or later, Nicolas Poussin (who also worked extensively in Rome). Instead, he was an individualist, an artist who synthesized various influences – the Carracci reform, Ferrarese romanticism, Northern landscape naturalism – into a highly personal style. His paintings, with their often turbulent energy and evocative moods, offer a compelling alternative to the more polished and idealized art of many of his contemporaries.

Art Historical Position and Enduring Appeal

Modern art historical scholarship has increasingly recognized the importance of artists like Donducci, who represent the rich diversity of Baroque art beyond its most famous protagonists. His work is valued for its originality, its emotional intensity, and its innovative approach to landscape. Exhibitions and scholarly publications have helped to bring his art to a wider audience, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of his place within the Bolognese School and Italian Baroque painting as a whole.

His paintings, such as The Virgin and Child with Saint Lucy, continue to be studied for their iconographic richness and their stylistic peculiarities. The experimental quality of his art, his willingness to prioritize expressive effect over academic convention, resonates with modern sensibilities that often value individuality and emotional directness.

In conclusion, Giovanni Andrea Donducci, "il Mastelletta," was more than just a minor master of the Bolognese School. He was an artist of considerable talent and originality, whose distinctive vision enriched the artistic landscape of his time. His spirited brushwork, his dramatic use of light, and his evocative, often untamed landscapes set him apart from many of his contemporaries. While he operated within the broader currents of the early Baroque, he navigated them with a singular independence, creating a body of work that remains compelling for its expressive power and its unique atmospheric charm. His legacy is that of an artist who, while rooted in tradition, dared to explore a more personal and unconventional path, leaving behind a testament to the enduring power of individual artistic expression.