Giovanni Battista Caracciolo, often known by his moniker Battistello, stands as a pivotal figure in the vibrant artistic landscape of early 17th-century Naples. Born in Naples in 1578, his life and career were profoundly shaped by the revolutionary artistic currents of his time, most notably the dramatic realism and tenebrism pioneered by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Caracciolo's journey from a local apprentice to one of the foremost exponents of Caravaggism in Naples is a testament to his talent, adaptability, and deep understanding of the power of light and shadow to convey human emotion and spiritual intensity. His death in Naples in 1635 marked the end of a significant chapter in Neapolitan art, but his legacy endured, influencing subsequent generations of painters in the city.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Caracciolo's artistic journey began in a Naples that was a bustling metropolis, a major European capital under Spanish rule, and a fertile ground for artistic innovation. His initial training is recorded as being under Francesco Imparato, a local painter whose style was rooted in the late Mannerist traditions prevalent in Naples at the close of the 16th century. This early exposure would have provided Caracciolo with a solid foundation in draughtsmanship and composition, though his mature style would diverge significantly from these beginnings.

The true turning point in Caracciolo's artistic development, and indeed for Neapolitan painting as a whole, was the arrival of Caravaggio in Naples. Caravaggio sought refuge in the city twice, first in 1606-1607 and again in 1609-1610. Though his stays were relatively brief, his impact was immediate and transformative. Caravaggio's radical naturalism, his use of ordinary people as models for sacred figures, and his dramatic deployment of chiaroscuro – the stark contrast of light and dark – captivated a generation of artists. Caracciolo, then in his late twenties and early thirties, was among the first and most receptive to this new artistic language.

While there is no definitive evidence that Caracciolo was a direct pupil in Caravaggio's workshop, he undoubtedly studied Caravaggio's Neapolitan works, such as the Seven Works of Mercy (Pio Monte della Misericordia) and the Flagellation of Christ (Museo di Capodimonte, originally San Domenico Maggiore), with intense scrutiny. He absorbed not just the superficial aspects of Caravaggio's style but its underlying principles: the direct observation of nature, the psychological intensity of his figures, and the theatrical use of light to heighten drama and focus the narrative.

Embracing the Caravaggesque Idiom

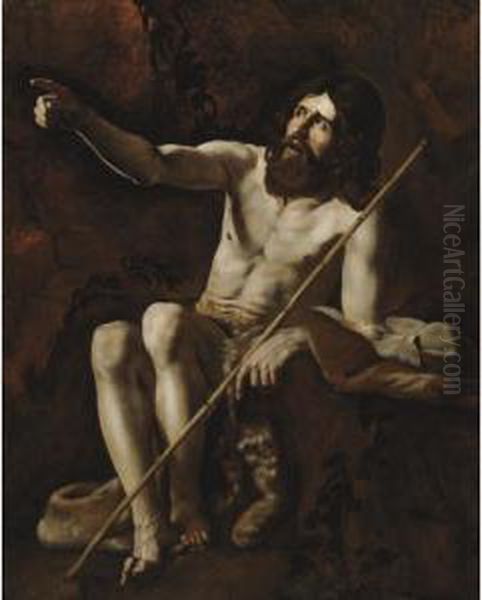

Caracciolo quickly became a leading figure among the "Caravaggisti," the followers of Caravaggio. His early works from around 1607-1615 demonstrate a profound assimilation of Caravaggio's tenebrism. Figures emerge from deeply shadowed backgrounds, illuminated by a strong, often raking light that sculpts their forms and emphasizes their physical presence. This is powerfully evident in one of his early masterpieces, the Liberation of Saint Peter (1608-1609), painted for the Pio Monte della Misericordia, the same charitable institution that housed Caravaggio's Seven Works of Mercy.

In the Liberation of Saint Peter, Caracciolo masterfully employs a restricted palette and dramatic lighting to convey the miraculous event. The angel, bathed in an ethereal glow, gently rouses the sleeping apostle, while the guards remain oblivious in the surrounding darkness. The figures possess a solidity and a naturalism that are hallmarks of the Caravaggesque style. Caracciolo's interpretation, however, also reveals his own sensibilities, perhaps a slightly more classical or monumental feel to the figures compared to Caravaggio's raw immediacy.

Other significant works from this period, such as the Calling of Saint Matthew (c. 1610-1615, Museo di Capodimonte), directly engage with Caravaggio's famous rendition of the same subject in the Contarelli Chapel in Rome. Caracciolo’s version, while clearly indebted to Caravaggio’s composition and lighting, shows his ability to reinterpret the theme with his own distinct artistic voice, focusing on the solemnity and spiritual gravity of the moment. His figures often possess a sculptural quality, their forms defined by strong contours and modeled by the interplay of light and shadow.

Travels and Stylistic Evolution

Around 1614, Caracciolo is documented as having traveled to Rome. This visit was crucial for his artistic development, exposing him to a wider range of artistic influences. In Rome, he would have encountered not only more of Caravaggio's works but also those of other Caravaggisti like Bartolomeo Manfredi, who was instrumental in popularizing Caravaggio's genre scenes, and Orazio Gentileschi, whose Caravaggism was tempered by a lyrical elegance and a refined palette. Artemisia Gentileschi, Orazio's daughter and a formidable painter in her own right, was also active and her powerful, dramatic works would later find resonance in Naples.

Furthermore, Rome was the center of the burgeoning Baroque style, with artists like Annibale Carracci and his Bolognese followers championing a more classical and idealized approach to painting, which stood in contrast to Caravaggio's stark realism. Caracciolo may also have seen works by early Baroque masters like Peter Paul Rubens, who had spent time in Italy. This exposure seems to have subtly inflected Caracciolo's style. While he remained fundamentally a Caravaggist, some of his later works show a slight softening of the harsh tenebrism, a greater richness in color, and a more complex approach to composition, possibly reflecting an absorption of these broader Italian artistic currents.

A trip to Florence is also recorded in 1617, and possibly to Genoa. In Florence, he would have encountered the works of the Florentine reformers like Cigoli and Passignano, who themselves were moving towards a more naturalistic and emotionally direct style. These experiences outside Naples broadened his artistic horizons and contributed to the increasing sophistication of his work.

Master of Fresco: The Certosa di San Martino

Upon his return to Naples, Caracciolo continued to be a dominant force. A significant aspect of his oeuvre, and one that distinguishes him from many other Caravaggisti who primarily worked in oil on canvas, was his mastery of fresco painting. This demanding technique, requiring rapid execution on wet plaster, was not typically associated with the deep shadows and intense contrasts of Caravaggism. However, Caracciolo successfully adapted his style to this medium.

His most celebrated achievement in fresco is the cycle depicting scenes from the life of Christ, including the monumental Washing of the Feet (1622), in the Chapel of Saint Martin within the Certosa di San Martino, a Carthusian monastery overlooking Naples. The Washing of the Feet is a tour de force of composition and narrative power. Caracciolo arranges numerous figures in a dynamic yet coherent space, using light not only for dramatic effect but also to clarify the narrative and guide the viewer's eye. The figures are robust and dignified, imbued with a solemn grandeur. This work is often considered the pinnacle of his career and a landmark of Neapolitan Baroque painting.

In these frescoes, while the Caravaggesque foundation is still apparent in the strong modeling of forms and the dramatic use of light, there is also a greater sense of classical balance and a brighter overall tonality compared to his earlier, more starkly tenebrist oils. This adaptation demonstrates his versatility and his ability to synthesize different artistic influences into a personal and powerful style. Other artists active in Naples, such as Belisario Corenzio, a prolific fresco painter of an older generation, provided a backdrop of more traditional large-scale decoration against which Caracciolo's innovative approach stood out.

The Neapolitan Artistic Milieu and Contemporaries

Caracciolo did not operate in a vacuum. Naples in the early 17th century was a vibrant artistic center, attracting painters from Italy and beyond. After Caravaggio's departure, Caracciolo was arguably the leading local proponent of his style. However, he was soon joined by other significant talents.

Jusepe de Ribera, a Spaniard who had also absorbed Caravaggio's lessons in Rome, settled in Naples in 1616. Ribera's powerful, often gritty realism and his own mastery of tenebrism made him a major figure, and at times a rival, to Caracciolo. While both artists shared a Caravaggesque heritage, their styles differed. Ribera's work often had a more pronounced Spanish inflection, with a particular intensity in the depiction of suffering and martyrdom. There was likely a degree of mutual influence and certainly a competitive artistic environment between them.

Giovanni Lanfranco, an artist from Parma who had trained with the Carracci in Bologna and later worked in Rome, also spent time in Naples (1634-1646, overlapping slightly with Caracciolo's final year). Lanfranco brought a more dynamic, High Baroque style, particularly in his illusionistic dome frescoes, which would have a significant impact on later Neapolitan painting. Though their primary stylistic allegiances differed, the presence of such diverse talents contributed to the richness of the Neapolitan school.

Other notable Neapolitan painters of the period included Massimo Stanzione, who, like Caracciolo, was influenced by Caravaggism but also developed a more classical and elegant style, sometimes drawing from Bolognese artists like Guido Reni and Domenichino (who also worked in Naples). Artemisia Gentileschi also spent a significant part of her career in Naples from 1630 onwards, further enriching the Caravaggesque current with her distinctive and powerful female voice. Artists like Filippo Vitale and Carlo Sellitto were also part of this first generation of Neapolitan Caravaggisti, each contributing to the diverse interpretations of Caravaggio's legacy. Even French artists like Simon Vouet and Valentin de Boulogne, who spent formative years in Italy, were part of the broader international Caravaggesque movement that Caracciolo engaged with during his Roman sojourn.

Caracciolo also painted secular works for private patrons, although religious commissions formed the bulk of his output. His versatility is noted in contemporary accounts, and his ability to adapt his style to different subjects and formats, from large altarpieces and frescoes to smaller devotional paintings, underscores his technical skill and artistic intelligence. His friendship with the Neapolitan writer Marco De Miledi, who wrote a poem in his honor and whose portrait Caracciolo painted, suggests his integration into the cultural life of the city.

Later Career and Legacy

In his later career, Caracciolo's style continued to evolve. Some scholars detect a move towards a more classical composure and a brighter palette in his works from the 1620s and early 1630s, possibly reflecting the influence of Bolognese classicism, which was gaining traction in Naples through artists like Domenichino and the works of Guido Reni. However, the fundamental principles of strong modeling, psychological intensity, and dramatic lighting derived from Caravaggio remained central to his art.

Works like the Trinitas Terribilis (Pietà dei Turchini, Naples) showcase his mature style, combining powerful, sculptural figures with a sophisticated use of light and a profound spiritual depth. His figures, often monumental in scale, convey a sense of gravitas and emotional weight. He continued to receive important commissions for churches throughout Naples, solidifying his reputation as one of the city's leading painters.

Giovanni Battista Caracciolo died in Naples in 1635. His death occurred at a time when Neapolitan painting was entering a new phase, with artists like Ribera, Stanzione, and soon the young Luca Giordano, pushing the boundaries of the Baroque style in different directions. Nevertheless, Caracciolo's contribution was foundational. He was instrumental in establishing Caravaggism as a dominant force in Neapolitan art, creating a powerful local interpretation of this revolutionary style.

His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent Neapolitan painters, who built upon the legacy of dramatic realism and expressive intensity that he, following Caravaggio, had championed. Artists like Mattia Preti, though of a later generation, would continue to explore the possibilities of tenebrism and dramatic narrative that Caracciolo had so masterfully developed. Even earlier figures like Fabrizio Santafede, representing an older, more Mannerist tradition, would have witnessed the sea-change brought about by Caravaggio and his followers like Caracciolo.

Conclusion: A Defining Force in Neapolitan Baroque

Giovanni Battista Caracciolo, or Battistello, remains a crucial figure for understanding the development of Baroque painting in Naples. As one of the earliest and most gifted followers of Caravaggio, he played a vital role in transplanting and transforming the master's revolutionary style onto Neapolitan soil. His powerful altarpieces and, uniquely among the Caravaggisti, his monumental frescoes, are characterized by their dramatic use of light and shadow, their profound psychological insight, and their solemn, often heroic, portrayal of sacred figures.

Through his engagement with the works of Caravaggio, his travels to other Italian artistic centers, and his interactions with contemporaries like Ribera and Lanfranco, Caracciolo forged a distinctive and influential artistic identity. He navigated the complex artistic currents of his time, absorbing diverse influences while remaining true to his Caravaggesque roots. His legacy is not merely that of an imitator, but of an innovator who adapted and personalized a powerful artistic language, leaving an indelible mark on the rich tapestry of Neapolitan art and securing his place as one of its most significant early Baroque masters. His works continue to resonate with their emotional power and artistic brilliance, testament to a career dedicated to the profound exploration of light, form, and the human spirit.