Andrea del Castagno, born Andrea di Bartolo di Bargilla around 1419-1423 in the village of Castagno d'Andrea near Florence, stands as one of the most formidable and influential figures of the Italian Early Renaissance. His relatively short life, ending in Florence in August 1457 due to plague, was marked by an intense artistic production characterized by powerful, sculptural figures, a keen understanding of perspective, and a dramatic, often stark, naturalism. His work embodies the intellectual and artistic ferment of 15th-century Florence, a city at the vanguard of a cultural rebirth that looked to classical antiquity for inspiration while forging new modes of expression. Castagno's art, though sometimes overshadowed by contemporaries who lived longer or whose personalities were less controversial, remains a crucial testament to the era's quest for realism, human dignity, and emotional depth in representation.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born in a rural area, Andrea del Castagno's early life was likely shaped by the rugged landscape of the Mugello region. His family were farmers. Political turmoil, specifically the wars between Florence and Milan, led to him spending time in Corella. His artistic inclinations must have been evident early on, as tradition, notably Giorgio Vasari in his "Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects," recounts that he was noticed by Bernadetto de' Medici. This Florentine nobleman, impressed by the young Andrea's untutored drawings, supposedly took him under his wing and facilitated his move to Florence around 1440 to pursue formal artistic training.

Once in Florence, Castagno was thrust into an environment teeming with artistic innovation. The towering figures of the preceding generation had already laid the groundwork for the Renaissance revolution. The painter Masaccio (Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Mone Cassai) had, before his early death in 1428, redefined painting with his frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel. Masaccio's use of single-point perspective, his mastery of chiaroscuro to create volumetric figures, and the grave, human dignity he imparted to his subjects profoundly impacted all subsequent Florentine art. Castagno undoubtedly studied Masaccio's work intently, absorbing lessons in monumentality and the convincing depiction of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface.

Equally significant was the influence of the sculptor Donatello (Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi). Donatello's dynamic figures, his profound understanding of human anatomy, and the psychological intensity he conveyed were revolutionary. Castagno's painted figures often possess a sculptural, almost tangible quality, a direct inheritance from Donatello's example. The raw energy and emotional force evident in many of Castagno's works echo Donatello's powerful expressiveness.

Another artist whose work likely informed Castagno's development was Paolo Uccello. Uccello was famously obsessed with the mathematical intricacies of perspective, and his complex spatial constructions, though sometimes more decorative than naturalistic, pushed the boundaries of pictorial science. Castagno, while perhaps less overtly experimental than Uccello, demonstrated a sophisticated command of perspective that grounded his figures firmly within their depicted environments. It is also believed that Castagno may have had some association with Fra Filippo Lippi, a prominent painter known for his lyrical grace and tender Madonnas, though Castagno's own style would diverge significantly towards a more robust and less idealized aesthetic.

Early Commissions and Rising Prominence

One of Castagno's earliest documented commissions, around 1440-1441, was a rather grim one: to paint frescoes of hanged traitors, the Albizzi conspirators and their allies, on the facade of the Palazzo del Podestà (now the Bargello Museum) after the Battle of Anghiari. This earned him the somewhat macabre nickname "Andreino degli Impiccati" (Little Andrea of the Hanged Men). While these works are now lost, the commission itself suggests a recognition of his skill in depicting figures with a stark, public impact.

A significant early period of activity occurred in Venice, where in 1442, Castagno, in collaboration with the lesser-known Francesco da Faenza, executed frescoes in the San Tarasio Chapel of the church of San Zaccaria. These works, including figures of God the Father, saints, and evangelists, show his developing style, with strong, clearly defined figures and an emerging sense of monumentality. The Venetian sojourn would have exposed him to different artistic currents, though the Florentine emphasis on disegno (drawing and design) remained central to his art.

Upon his return to Florence, Castagno's career gained momentum. He designed a stained-glass window depicting the Deposition from the Cross for the drum of Florence Cathedral in 1444. This commission, for such a prominent civic and religious edifice, indicates his growing stature. Around the same time, he is documented as having joined the Arte de' Medici e Speziali, the Florentine guild that painters belonged to, a necessary step for establishing an independent workshop.

The Sant'Apollonia Frescoes: A Landmark Achievement

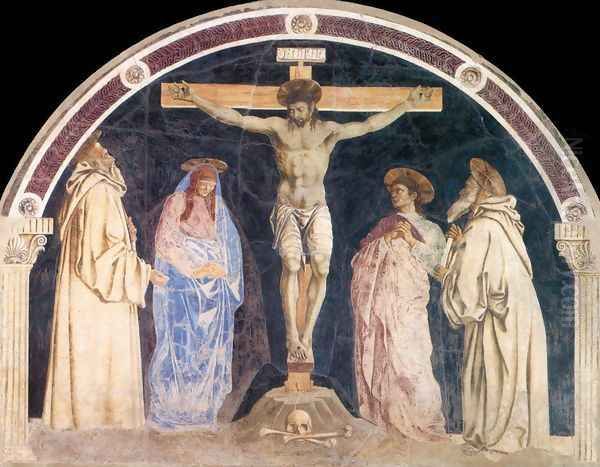

The period between 1445 and 1450 saw the creation of what are arguably Castagno's most celebrated works: the frescoes for the refectory (dining hall) of the Benedictine convent of Sant'Apollonia in Florence. Rediscovered in the 19th century after the convent's suppression, these frescoes are a cornerstone of Early Renaissance art. The main scene, The Last Supper, occupies the lower register of the wall, while above it, originally separated by a painted cornice that created an illusion of a separate space, were scenes of the Crucifixion, Entombment, and Resurrection (these upper scenes are now somewhat damaged and detached for conservation).

The Last Supper at Sant'Apollonia is a work of extraordinary power and psychological insight. Castagno sets the scene within a meticulously rendered classical architectural framework, employing scientific perspective to create a convincing illusion of depth. The apostles are arranged along a long table, with Christ at the center. Judas Iscariot is dramatically isolated on the opposite side of the table, facing the viewer, a common iconographic convention but rendered by Castagno with particular force. The figures are robust and individualized, their faces and gestures conveying a range of emotions in response to Christ's announcement of betrayal. The use of strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) enhances their sculptural solidity. The attention to detail in the setting, from the marble panels on the walls to the food on the table, contributes to the scene's vivid realism. This work predates Leonardo da Vinci's more famous version by several decades and offers a more rugged, less idealized interpretation of the subject.

The upper scenes of the Passion, though less well-preserved, continue this emphasis on dramatic intensity and physical presence. The Crucifixion is stark and sorrowful, while the Resurrection depicts a powerful, triumphant Christ. These frescoes, taken together, demonstrate Castagno's mastery of large-scale narrative composition, his ability to convey profound religious themes with human immediacy, and his technical command of fresco painting. The Sant'Apollonia complex now houses the Museo di Cenacolo di Sant'Apollonia, centered around these magnificent works.

The Villa Carducci Cycle: Illustrious Men and Women

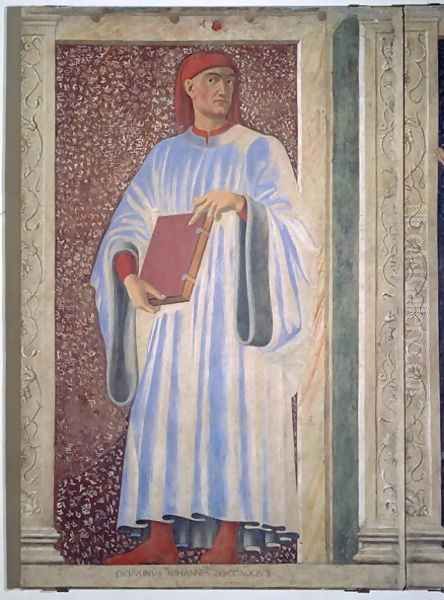

Another major fresco cycle, dating from around 1448-1451, was created for the Loggia of the Villa Carducci (now Villa Carducci-Pandolfini) at Legnaia, just outside Florence. These were secular subjects, a series of Uomini Famosi (Famous Men) and Donne Famose (Famous Women), figures drawn from biblical, classical, and Florentine history, embodying various virtues. The surviving figures, detached and now housed in the Uffizi Gallery, include military leaders like Pippo Spano and Farinata degli Uberti, literary giants Dante Alighieri, Petrarch, and Giovanni Boccaccio, and powerful women such as the Cumaean Sibyl, Queen Esther, and Queen Tomyris.

These figures are depicted standing in illusionistic niches, again showcasing Castagno's skill in perspective and his ability to create a sense of monumental, statuesque presence. Each figure is imbued with a distinct personality and a sense of gravitas. Pippo Spano, for instance, is a commanding military figure, clad in armor, while Dante appears as a stern, thoughtful poet. These frescoes reflect the humanist interests of the period, celebrating individual achievement and virtue. The sculptural quality of these figures is particularly pronounced, almost as if they are painted statues. The influence of Donatello's sculptures, such as his prophets for the Florence Campanile, is palpable. The Villa Carducci cycle is a significant example of the revival of this classical theme in Renaissance art, a theme also explored by artists like Taddeo Gaddi in the 14th century, but given new life and vigor by Castagno.

Later Works and Stylistic Maturity

Castagno continued to be active in Florence throughout the 1450s. He painted an Assumption of the Virgin with Saints Julian and Minias for the church of San Miniato fra le Torri (now in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), a work notable for its strong emotional content and the solid, almost severe, depiction of the figures.

Around 1455, he contributed to the decoration of the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata in Florence. Here, he painted a powerful Saint Julian and the Redeemer and a Trinity with Saint Jerome and Two Female Saints. These frescoes demonstrate his mature style, characterized by an unwavering commitment to anatomical accuracy, dramatic intensity, and a certain austerity. His figures are often depicted with a rugged, unidealized realism that sets him apart from the more lyrical tendencies of some of his contemporaries like Fra Angelico or the aforementioned Filippo Lippi.

One of his last major commissions, completed in 1456, was the Equestrian Monument of Niccolò da Tolentino in Florence Cathedral. This fresco was intended as a pendant to Paolo Uccello's earlier Equestrian Monument of Sir John Hawkwood. Both are illusionistic depictions of bronze statues, painted in terra verde (green earth pigment) to mimic patinated bronze. Castagno's version is arguably more dynamic and three-dimensional than Uccello's, with a greater sense of movement and a more robust modeling of the horse and rider. It showcases his ability to tackle monumental public commissions and his continued engagement with the problems of perspective and illusionism.

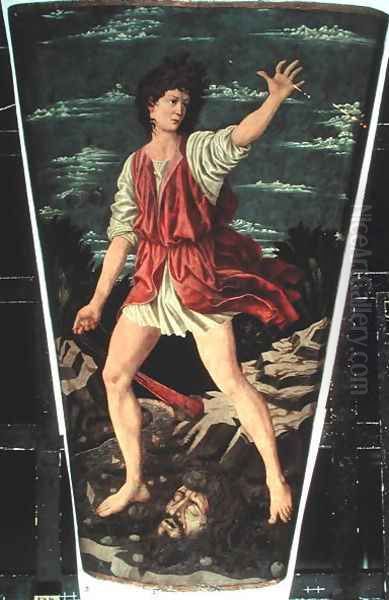

Other notable works from his mature period include the David with the Head of Goliath, a dynamic and youthful depiction painted on a leather shield (now in the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.), and a Crucifixion for the Strozzi Chapel in Santa Maria Novella (though attribution here is sometimes debated). His Saint Sebastian, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, is a poignant depiction of the martyred saint, showcasing Castagno's skill in rendering the human form under duress, a theme also explored with great power by artists like Antonio del Pollaiuolo, who was known for his interest in anatomy and muscular tension.

The Vasari Controversy: A Tarnished Reputation?

Andrea del Castagno's posthumous reputation was significantly, and unfairly, damaged by a story circulated by Giorgio Vasari. In his "Lives," Vasari accused Castagno of murdering his fellow artist and friend, Domenico Veneziano, out of professional jealousy. Veneziano was a master of color and light, and Vasari claimed that Castagno, envious of Veneziano's skill in oil painting (a technique Veneziano helped pioneer in Florence), feigned friendship only to ambush and kill him.

This dramatic tale of artistic rivalry turned deadly persisted for centuries, casting a dark shadow over Castagno's name. However, historical research has thoroughly debunked Vasari's account. Archival records show that Domenico Veneziano actually outlived Andrea del Castagno by four years; Castagno died of the plague in 1457, while Veneziano died in 1461. Vasari, writing several decades after the events, was either misinformed, relying on unreliable gossip, or perhaps conflated Castagno with another artist or incident.

While the murder accusation is false, it is plausible that a strong artistic rivalry existed between Castagno and Veneziano. The Florentine art world was highly competitive, and artists frequently vied for commissions and prestige. Veneziano's style, characterized by its luminous palette and delicate handling of light, was quite different from Castagno's more forceful and sculptural approach. They did work in proximity, for instance, on frescoes (now lost) in the church of Sant'Egidio (part of the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova). It is likely that they influenced each other, even if their artistic temperaments differed. The debunking of Vasari's story allows for a more objective assessment of Castagno's character and his artistic relationships.

Artistic Style: Power, Realism, and Monumentality

Andrea del Castagno's artistic style is defined by several key characteristics:

Sculptural Form and Monumentality: His figures possess a remarkable sense of weight and three-dimensionality, often appearing as if carved from stone. This is a direct legacy of Donatello and Masaccio. Even in his narrative scenes, individual figures often have a self-contained, statuesque quality.

Anatomical Realism and Energy: Castagno had a strong grasp of human anatomy, and his figures, particularly male nudes or heavily muscled heroes, are rendered with a powerful, sometimes raw, energy. His lines are often sharp and incisive, defining forms with clarity and strength. This interest in anatomical accuracy and dynamic movement would be further developed by artists like Antonio del Pollaiuolo and later, Luca Signorelli, whose frescoes at Orvieto Cathedral display a similar fascination with the human body in action.

Psychological Intensity: While not always subtle, Castagno was adept at conveying strong emotions. His figures often possess a stern, brooding, or intensely focused demeanor. In The Last Supper, the varied reactions of the apostles are a testament to his ability to depict psychological states.

Mastery of Perspective: Like many of his Florentine contemporaries, Castagno was deeply interested in the new science of perspective. He used it effectively to create convincing spatial environments for his figures, enhancing the illusion of reality in his frescoes.

Strong Chiaroscuro: He employed strong contrasts of light and shadow to model his figures and create dramatic effects. This contributed to their sculptural quality and heightened the emotional impact of his scenes.

Austerity and Lack of Idealization: Compared to some of his contemporaries, Castagno's figures are often less idealized and more ruggedly naturalistic. There is a certain severity and directness in his art, a preference for strength over grace, which gives his work a distinctive and powerful voice. This contrasts with the more delicate and often sweeter style of artists like Fra Angelico or the decorative elegance that would later characterize the work of Sandro Botticelli.

Legacy and Influence

Despite his relatively short career and the later cloud over his reputation, Andrea del Castagno was a significant force in 15th-century Florentine art. His powerful, realistic style and his mastery of monumental fresco painting left a lasting impression. He pushed the boundaries of naturalism and emotional expression, building upon the innovations of Masaccio and Donatello.

His influence can be seen in the work of slightly younger artists. The Pollaiuolo brothers, Antonio and Piero del Pollaiuolo, shared his interest in anatomical rendering and dynamic movement. While it's difficult to trace direct lines of influence for every major succeeding artist, Castagno's robust and sculptural approach to the human figure certainly contributed to the artistic vocabulary available to later masters like Andrea Mantegna in Padua (whose own style was similarly statuesque and powerful) and even the young Michelangelo Buonarroti, whose figures possess an unparalleled terribilità (awesomeness or terrifying power) that finds some precedent in the forceful energy of Castagno's art.

Castagno's commitment to depicting the human form with strength and dignity, grounded in a keen observation of reality and a sophisticated understanding of pictorial science, places him firmly within the mainstream of Early Renaissance innovation. He was a pivotal figure in the transition from the more experimental phase of the early 15th century towards the High Renaissance.

Conclusion: An Enduring Florentine Master

Andrea del Castagno remains a compelling and somewhat enigmatic figure. His art, characterized by its unyielding strength, its often stark realism, and its profound psychological depth, offers a powerful counterpoint to the more lyrical or decorative trends in Quattrocento painting. From the dramatic intensity of the Sant'Apollonia Last Supper to the monumental dignity of the Villa Carducci Famous Men and Women, Castagno's work consistently demonstrates a singular artistic vision.

He was a master of fresco, capable of commanding large wall surfaces with complex, coherent compositions. His figures, imbued with a sense of physical and moral weight, reflect the humanist emphasis on individual potential and earthly achievement. Though his life was cut short, Andrea del Castagno's contribution to the Florentine Renaissance was substantial. He was an artist of uncompromising integrity and formidable power, whose works continue to impress viewers with their directness, their technical brilliance, and their enduring human relevance. His legacy is that of a true innovator, a painter who captured the vigorous spirit of his age with an intensity that remains palpable to this day.