Giovanni Battista Piranesi stands as a colossus in the landscape of 18th-century European art. Born near Venice on October 4, 1720, and dying in Rome on November 9, 1778, his life spanned a period of intense cultural ferment, archaeological discovery, and shifting artistic sensibilities. Primarily celebrated as a master etcher, Piranesi was also a practicing architect, a pioneering archaeologist, a polemical theorist, and a shrewd businessman. His dramatic, often fantastical visions of ancient Rome not only captured the imagination of his contemporaries but continue to resonate, influencing fields as diverse as architecture, stage design, literature, and even filmmaking. He remains a figure whose work defies easy categorization, bridging the rational spirit of Neoclassicism with the burgeoning emotional intensity of Romanticism.

Venetian Foundations and Early Aspirations

Piranesi's origins lay in the Veneto region, specifically Mogliano Veneto (or nearby Moglio di Mestre, sources vary slightly), territory of the Republic of Venice. His father, Angelo Piranesi, was a stonemason and master builder, providing a foundational connection to the world of construction. His mother, Laura Lucchesi, was the sister of Matteo Lucchesi, a respected architect and engineer for the Venetian Magistrato delle Acque (Magistracy of the Waters), the body responsible for the Republic's complex hydraulic systems. This familial link proved crucial. Young Giovanni Battista received his initial training in architecture and engineering principles under the tutelage of his uncle Matteo, gaining practical knowledge alongside theoretical understanding.

Further shaping his early development was his brother, Angelo Piranesi, a Carthusian monk. Angelo possessed a deep knowledge of classical literature and history, and he reportedly instilled in his younger sibling a profound admiration for the achievements of ancient Rome, firing an interest that would become a lifelong obsession. Venice itself, a city built on water and theatricality, with its own rich architectural heritage and vibrant artistic scene dominated by figures like Canaletto, Bernardo Bellotto, and the great ceiling painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, provided a stimulating, if ultimately constraining, environment. Piranesi also absorbed the principles of perspective and stage design, possibly influenced by the work of the renowned Bibiena family, masters of Baroque scenography. This understanding of dramatic spatial composition would become a hallmark of his later work.

The Lure of the Eternal City

Around 1740, at the age of twenty, Piranesi left Venice for Rome. This move was pivotal. He initially arrived as a draughtsman in the entourage of Marco Foscarini, the Venetian ambassador to the Papal States. Rome, the former heart of a vast empire, presented a stark contrast to Venice. Its sprawling ruins, testaments to a glorious and powerful past, exerted an immediate and overwhelming fascination on the young artist. The sheer scale and fragmented majesty of ancient structures like the Colosseum, the Pantheon, and the Baths of Caracalla offered endless subjects for his burgeoning artistic vision.

In Rome, Piranesi sought to refine his skills, particularly in the art of etching. He studied briefly but significantly with Giuseppe Vasi, a leading Sicilian printmaker known for his own views of Rome. While Vasi's style was more conventionally topographical, the apprenticeship provided Piranesi with essential technical grounding in the etching process. However, Piranesi's fiery temperament and ambition reportedly led to friction, and he soon struck out on his own. He may have also absorbed influences from other Roman artists and architects, immersing himself in the city's artistic milieu, which included established view painters like Giovanni Paolo Pannini, known for his picturesque depictions of ruins and Roman festivals. The grandeur and decay of Rome provided the perfect canvas for Piranesi's unique blend of archaeological interest and dramatic sensibility.

Early Works and Establishing Independence

Piranesi quickly began producing his own prints. His first major published work, the Prima Parte di Architetture e Prospettive (First Part of Architecture and Perspectives), appeared in 1743. This collection already showcased his distinctive approach: imaginative architectural compositions, often based on Roman elements but rearranged into novel and sometimes impossible configurations, demonstrating his mastery of perspective and his burgeoning interest in architectural fantasy. These early works revealed an artist grappling with the legacy of antiquity, not merely documenting it, but actively reinterpreting it.

An anecdote from this early period highlights both his ambition and his volatile nature. He secured patronage from an Irish nobleman, James Caulfield, the future Lord Charlemont, for a series of etchings. When Caulfield allegedly failed to provide the promised funds after returning to Ireland, Piranesi felt betrayed. In a later edition of the Prima Parte, he dramatically re-etched the dedication plate, effacing Caulfield's name and adding pointed imagery and inscriptions alluding to the broken promise. This incident reveals Piranesi's fierce independence and his willingness to use his art as a vehicle for personal expression, even score-settling. In 1753, he married Angela Pasquini, the daughter of a gardener in the Corsini Palace. The marriage provided stability, and Angela reportedly played an active role in his burgeoning business, managing aspects of the workshop and print sales. They would have five children, several of whom, notably Francesco, would follow in their father's artistic footsteps.

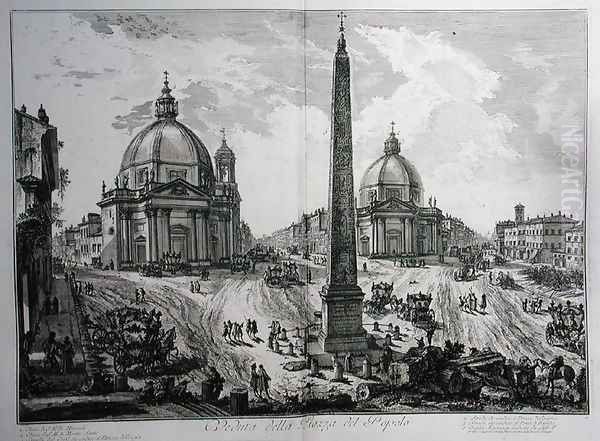

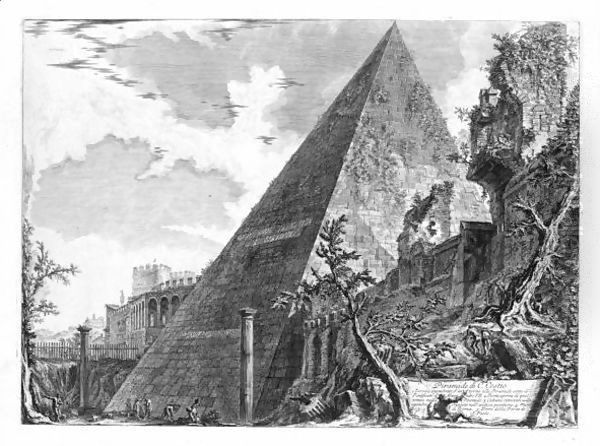

Capturing Rome: The Vedute di Roma

Piranesi's most extensive and commercially successful project was the Vedute di Roma (Views of Rome). Begun in the mid-1740s and continually expanded until his death, this vast series eventually comprised 135 large-scale etchings depicting the monuments and landscapes of ancient and contemporary Rome. These were not mere topographical records like those of his teacher Vasi or the precise cityscapes of Canaletto. Piranesi infused his views with an unprecedented sense of drama and monumentality. He employed low viewpoints to exaggerate the scale of buildings, used dramatic contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to heighten mood, and populated his scenes with small, often gesticulating figures that emphasized the colossal nature of the ruins surrounding them.

The Vedute captured both the picturesque decay and the enduring grandeur of Rome. He depicted famous landmarks like St. Peter's Basilica, the Castel Sant'Angelo, the Trevi Fountain, and the Spanish Steps, alongside countless views of temples, arches, bridges, and tombs. His technique became increasingly bold over the years, with deep, vigorous lines and rich tonal variations achieved through multiple bitings of the copper plate. These prints were immensely popular, particularly with the growing number of wealthy northern Europeans undertaking the Grand Tour. For many visitors, Piranesi's etchings became the definitive visual record of their Roman experience, shaping the collective European imagination of the Eternal City for generations. They were souvenirs, study aids, and powerful artistic statements rolled into one.

Descent into Fantasy: The Carceri d'Invenzione

While the Vedute cemented his popular reputation, Piranesi's most enigmatic and arguably most influential work is the Carceri d'Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons). This series of etchings exists in two distinct states. The first, comprising 14 plates, was likely created around 1745 and published circa 1750. These initial versions are relatively lighter in tone and execution. Around 1761, Piranesi revisited the plates, extensively reworking them, adding two new compositions, and darkening the overall atmosphere considerably through dense cross-hatching and deeper etching. This second state, with its 16 plates, is the one most commonly known today.

The Carceri depict vast, subterranean architectural spaces filled with immense arches, crumbling staircases leading nowhere, precarious catwalks, and strange, menacing machinery – ropes, chains, levers, and instruments of ambiguous purpose. Human figures are dwarfed by the overwhelming scale of the architecture, appearing as tiny, often tormented souls lost within these oppressive labyrinths. The perspective is often deliberately confusing, creating a sense of spatial disorientation and psychological unease. These are not depictions of real prisons but rather explorations of architectural fantasy, spatial complexity, and the darker aspects of the human psyche. They draw on Piranesi's knowledge of Roman engineering (aqueducts, vaults) and his background in stage design, but transform these elements into something entirely new and deeply personal. The Carceri have been interpreted in myriad ways: as critiques of absolute power, reflections on the sublime and terrifying aspects of human creation, explorations of existential dread, or simply as exercises in imaginative design. Their influence extends far beyond the 18th century, resonating with Romantic writers like Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Thomas De Quincey, and later artists associated with Symbolism and Surrealism, such as Max Ernst, and even filmmakers drawn to dystopian or fantastical settings. The Dutch graphic artist M.C. Escher, with his impossible perspectives, owes a clear debt to Piranesi's visionary prisons.

The Archaeologist and Polemicist

Piranesi was not content merely to depict Rome; he sought to understand and interpret its past. He engaged actively in archaeological investigation, exploring sites and documenting finds. His monumental four-volume work, Le Antichità Romane (Roman Antiquities), published in 1756, presented over 200 etchings meticulously documenting the ruins of Rome, including plans, sections, elevations, and detailed views of construction techniques and decorative fragments. This work was a landmark in archaeological publication, providing invaluable data for scholars and architects, even if Piranesi's reconstructions sometimes involved a degree of imaginative interpretation. He documented tombs along the Appian Way, the foundations of buildings, and ancient engineering works, driven by a desire to showcase the ingenuity and magnificence of Roman civilization.

This passion led him into theoretical debate. In Della Magnificenza ed Architettura de' Romani (On the Magnificence and Architecture of the Romans, 1761), Piranesi mounted a vigorous defense of the originality and superiority of Roman architecture, particularly against the prevailing Neoclassical taste that increasingly favored the perceived purity and simplicity of ancient Greek art. This pro-Greek view was most famously championed by the highly influential German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann. Piranesi argued that Roman architecture was not merely derivative of Greek models but had its own distinct roots in earlier Etruscan and Italic traditions, emphasizing Roman engineering prowess and decorative richness. This sparked a significant intellectual controversy, pitting Piranesi's passionate Roman patriotism against Winckelmann's Hellenic ideal. He further elaborated his views in works like Parere su l'architettura (Opinion on Architecture, 1765), where he defended artistic license and the creative use of ornament against what he saw as overly rigid functionalist doctrines, advocating for a richer, more eclectic approach to design.

Piranesi as Architect: Santa Maria del Priorato

Despite his extensive theoretical engagement with architecture and his background in the field, Piranesi completed only one significant architectural project: the redesign and redecoration of the church of Santa Maria del Priorato on the Aventine Hill in Rome. Commissioned around 1764 by Cardinal Giovanni Battista Rezzonico, the nephew of Pope Clement XIII (a fellow Venetian) and Grand Prior of the Knights of Malta, the project involved renovating the existing medieval church and designing the adjacent piazza, the Piazza dei Cavalieri di Malta.

Completed by 1766, the church is a fascinating built manifestation of Piranesi's eclectic theories and decorative imagination. The facade and interior stucco work are densely packed with an unconventional mix of motifs drawn from Roman, Greek, Egyptian, Etruscan, and even Mannerist sources. Military and naval symbols relating to the Knights of Malta abound, interwoven with sphinxes, obelisks, fasces, skulls, and intricate vegetal patterns. The overall effect is highly original, intensely decorative, and somewhat idiosyncratic – a stark contrast to the more restrained classicism favored by many contemporaries. The piazza itself, with its ornamental entrance wall featuring the famous keyhole view of St. Peter's Basilica, further showcases Piranesi's unique design sensibility. While a singular achievement, Santa Maria del Priorato demonstrates Piranesi's ability to translate his graphic visions into three-dimensional form, creating a space saturated with historical allusion and symbolic meaning.

The Workshop, Later Years, and Antiquities

Throughout his career, Piranesi operated a highly productive workshop near the Spanish Steps in Rome (Palazzo Tomati on Strada Felice). This served as a studio, a print shop, a publishing house, and a gallery for selling his etchings and potentially dealing in actual Roman antiquities he sometimes acquired or excavated. His operation was a family affair. His wife Angela managed business aspects, and his children, particularly Francesco and Laura, were trained as etchers and assisted in the production process. Laura became a talented printmaker in her own right, while Francesco became his father's primary collaborator and successor.

In his later years, Piranesi continued to produce Vedute and undertook new projects. He traveled south to Naples and visited the recently excavated sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum, documenting his findings. He also journeyed to the ancient Greek temples at Paestum, south of Naples, producing a series of powerful etchings of these Doric structures. These were published posthumously by Francesco in 1778. Piranesi remained fiercely productive until the end. He was elected an Honorary Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1757 and received a knighthood (Order of the Golden Spur) from Pope Clement XIII, allowing him to style himself 'Cavaliere Piranesi'. He died in Rome in 1778, reportedly after a prolonged illness, and was buried in his own creation, Santa Maria del Priorato.

Enduring Influence and Legacy

Giovanni Battista Piranesi's impact on Western art and culture is profound and multifaceted. His technical mastery of etching set a new standard for the medium, demonstrating its potential for dramatic expression and tonal richness. His Vedute di Roma shaped the visual perception of the city for centuries and remain iconic representations of its historical grandeur. The Carceri d'Invenzione, with their psychological depth and visionary power, transcended their time to become touchstones for Romanticism, Symbolism, and Surrealism, influencing artists from Henry Fuseli and Francisco Goya (whose own dark prints like Los Caprichos share a certain intensity) to 20th-century figures.

In architecture and design, his influence was both direct and indirect. Architects like the Scottish Neoclassicist Robert Adam explicitly drew inspiration from Piranesi's detailed renderings of Roman ornament and his imaginative compositions for their own interior designs. Others, like Sir John Soane in England or perhaps Étienne-Louis Boullée and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux in France, absorbed his sense of scale, drama, and architectural fantasy. His defense of Roman originality and decorative freedom provided a counterpoint to stricter Neoclassical doctrines, enriching the architectural discourse of the era. His archaeological publications, despite occasional inaccuracies by modern standards, were pioneering efforts in documenting and disseminating knowledge of the ancient world, stimulating further study. Even literary figures felt his impact; while Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, upon finally visiting Rome, found the reality less dramatic than Piranesi's prints suggested, those very prints had helped fuel his desire to see the city. Piranesi remains a vital figure, an artist whose obsessive engagement with the past produced visions that were startlingly forward-looking.

Controversies and Critical Reception

Piranesi's career was not without controversy. His polemical writings, particularly his staunch defense of Roman architectural superiority against the Hellenic ideal promoted by Winckelmann, placed him at odds with powerful intellectual currents of his time. His public falling-out with Lord Charlemont over patronage demonstrated his prickly independence. Furthermore, his approach to archaeological representation, while groundbreaking in its scope and detail, sometimes prioritized artistic effect over strict scientific accuracy, blending observed reality with imaginative reconstruction.

His critical reception has also fluctuated. While immensely popular during his lifetime, particularly among Grand Tourists, later critics sometimes struggled to place his unique blend of styles. Some Neoclassicists found his work overly dramatic or fantastical. Romantic writers and artists, conversely, celebrated the visionary power of the Carceri. In the later 19th and early 20th centuries, his work was occasionally marginalized or misunderstood, seen perhaps as eccentric rather than central to the main currents of art history. However, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized the complexity, originality, and far-reaching influence of his oeuvre, appreciating his role as a crucial transitional figure and a master printmaker of unparalleled imaginative force.

Conclusion: Architect of Shadows and Substance

Giovanni Battista Piranesi was more than just an etcher of Roman views. He was an artist consumed by the past but driven by a restless, modern sensibility. His work embodies a tension between meticulous observation and boundless imagination, between archaeological documentation and architectural fantasy. Through the demanding medium of etching, he conjured visions of antiquity that were both awe-inspiring and unsettling, capturing the grandeur, the decay, and the enduring mystery of Rome. He challenged the artistic and architectural orthodoxies of his day, championed the legacy of his adopted city, and created images of such power and originality that they continue to haunt and inspire. From the sunlit ruins of the Forum in his Vedute to the oppressive, labyrinthine depths of his Carceri, Piranesi remains a singular figure in art history – an architect not just of stone and stucco, but of shadow, dream, and enduring memory.