Marco Ricci stands as a pivotal figure in the transition of Italian art during the late Baroque and early Rococo periods. Born in Belluno, Republic of Venice, on June 5, 1676, and passing away in Venice on January 21, 1730, Ricci carved a unique niche for himself primarily as a landscape painter, but also as a master of the capriccio (architectural fantasy) and a significant early proponent of etching in eighteenth-century Venice. His work bridged the more dramatic, classical landscapes of the seventeenth century with the lighter, more atmospheric vedute (view paintings) that would come to define the Venetian School in the age of Canaletto and Guardi. His influence extended beyond Italy, particularly to England, where he spent several formative years.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Marco Ricci's artistic journey began under the significant shadow and guidance of his uncle, Sebastiano Ricci (1659–1734), a prominent history painter of the Venetian School. Born into a family with artistic inclinations, Marco likely received his initial training from Sebastiano in Venice. Details of his very early life are somewhat obscured, with some accounts suggesting a turbulent youth. A persistent, though not definitively proven, anecdote claims that a young Marco killed a gondolier in a brawl, forcing him to flee Venice.

Regardless of the veracity of this story, it is known that Ricci spent time away from Venice in his formative years. He is documented as working alongside his uncle Sebastiano in Florence around 1706-1707. There, they collaborated on decorative schemes, most notably frescoes in the Palazzo Fenzi (now housing part of the University of Florence), specifically decorating the Sala d'Ercole. This collaboration often saw Sebastiano painting the figures while Marco contributed the landscape or architectural backgrounds, a pattern that would recur in their joint projects. This period exposed Marco to the Florentine artistic environment and likely broadened his understanding of large-scale decorative painting.

Travels and Exposure to New Influences

Ricci's travels were crucial to the development of his style. Following his time in Florence, he is believed to have spent time in Rome. The Eternal City, with its wealth of classical ruins and the legacy of seventeenth-century landscape painters, profoundly impacted him. The works of French masters active in Rome, such as Claude Lorrain (1600–1682) and Gaspard Dughet (1615–1675), with their idealized classical landscapes, offered models of composition and atmospheric light. Equally important was the influence of the Neapolitan painter Salvator Rosa (1615–1673), known for his wilder, more romantic and picturesque landscapes featuring bandits, dramatic rock formations, and tempestuous weather.

Some art historians also suggest a period spent in Milan, where Ricci may have encountered the work of Alessandro Magnasco (1667–1749). Magnasco, known for his highly individual style featuring elongated, flickering figures set within dramatic landscapes or interiors, sometimes collaborated with landscape specialists. While direct collaboration between Ricci and Magnasco is debated, the potential exposure to Magnasco's expressive brushwork and dramatic flair could have contributed another layer to Ricci's evolving artistic sensibility. These varied influences – the classical idealism of Lorrain, the picturesque wildness of Rosa, and the potential dynamism of Magnasco – were synthesized by Ricci into his own unique vision.

The English Sojourn: Stage Design and Patronage

A significant chapter in Marco Ricci's career unfolded in England. In 1708, he traveled to London, likely at the invitation of Charles Montagu, 4th Earl of Manchester (later 1st Duke of Manchester), who was serving as the British ambassador to Venice. He was accompanied initially by the Venetian painter Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (1675–1741). Their primary task was to create stage designs for the burgeoning Italian opera scene at the Queen's Theatre (later King's Theatre) in the Haymarket. This involved painting elaborate backdrops and scenery, demanding quick execution and dramatic effect.

Ricci's work for the theatre was well-received and placed him at the heart of London's fashionable cultural life. He collaborated with Pellegrini on several projects, but their relationship was reportedly marked by rivalry. While in England, Ricci had ample opportunity to study landscapes by Dutch and Flemish masters, whose works were popular among English collectors. Artists like Jacob van Ruisdael (c. 1629–1682) and Meindert Hobbema (1638–1709), with their detailed observation of nature and sophisticated rendering of light and weather, offered a different perspective from the Italian tradition. This exposure likely reinforced Ricci's inclination towards naturalism within his landscape painting.

His uncle Sebastiano Ricci joined him in London around 1711 or 1712. Together, they undertook several prestigious decorative commissions, including work at Burlington House for Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, a key figure in promoting Palladian architecture, and at Cannons for the Duke of Chandos. Marco often provided the landscape or architectural settings for Sebastiano's historical or mythological figures. Marco Ricci returned to Venice in 1716, enriched by his experiences, exposure to different artistic traditions, and connections with influential patrons.

Maturity in Venice: Landscape and Capriccio

Upon his return to Venice, Marco Ricci entered his most productive and defining period. He largely abandoned large-scale decorative painting and focused intently on easel paintings, drawings, and etchings, primarily landscapes and capricci. He established himself as a leading specialist in these genres, finding a ready market among Venetian collectors and foreign visitors on the Grand Tour. His English experience had not only honed his skills but also likely increased his reputation back home.

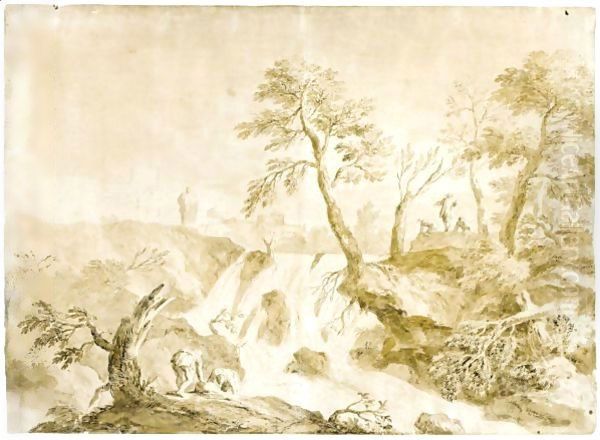

During this mature phase, Ricci developed a distinctive style characterized by lively brushwork, a keen sensitivity to atmospheric effects, and often dramatic compositions. He frequently worked in tempera on kidskin (goat parchment) or leather, a technique that allowed for a particular luminosity and freshness of color, distinct from the deeper tones often associated with oil painting. These tempera works, often relatively small in scale, possess a jewel-like quality and were highly sought after. His subjects ranged from pastoral scenes reminiscent of the Venetian mainland (the terraferma) to stormy coastal views, tranquil woodland settings, and evocative winter landscapes.

His landscapes often feature small, lively figures – peasants, travellers, washerwomen – that animate the scene and provide scale, but the primary focus remains the natural environment itself. He masterfully captured the play of light and shadow, the textures of foliage and rock, and the changing moods of nature. Works like Landscape with Washerwomen exemplify his ability to blend observed reality with a picturesque sensibility, creating scenes that feel both grounded and idyllic.

Master of the Capriccio

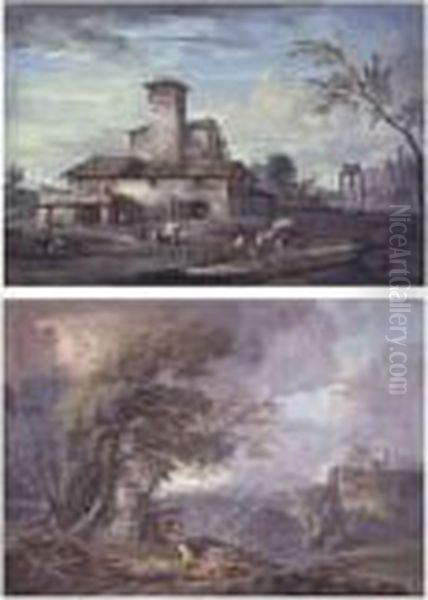

Alongside pure landscape, Marco Ricci excelled in the genre of the capriccio. A capriccio, in this context, refers to an architectural fantasy, a painting or print where real, imaginary, and rearranged architectural elements, often classical ruins, are combined in picturesque compositions. This genre allowed artists greater freedom of invention than topographical view painting (veduta). Ricci was one of the earliest and most influential practitioners of the capriccio in eighteenth-century Venice.

His capricci often draw upon his experiences in Rome, featuring crumbling arches, broken columns, pyramids, and sarcophagi, sometimes juxtaposed with more contemporary or rustic structures. These scenes are rarely melancholic meditations on decay; instead, they are often animated by small figures going about their daily lives, creating a lively contrast between the grandeur of the past and the immediacy of the present. The compositions are carefully constructed, balancing architectural masses with open spaces and using light and shadow to create depth and drama.

Ricci's capricci paved the way for later masters of the genre, most notably Giovanni Paolo Pannini (1691–1765) in Rome, who further developed the theme of depicting collections of real and imagined monuments. In Venice, Ricci's approach influenced the capricci produced by artists like Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal, 1697–1768) and Francesco Guardi (1712–1793), although their interpretations would evolve in different directions. Ricci's contribution was crucial in establishing the capriccio as a significant and popular genre within Venetian painting.

Pioneer of Etching

Marco Ricci also holds an important place in the history of printmaking as one of the pioneers of original etching in eighteenth-century Venice. Although he apparently came to the medium relatively late in his career, around 1723, he quickly mastered it. Etching offered him a way to replicate and disseminate his landscape and capriccio compositions to a wider audience. His etched work closely mirrors the style and subject matter of his paintings and drawings.

His etchings are characterized by a free, painterly line that effectively captures atmospheric effects and the textures of nature – gnarled trees, rough-hewn buildings, cloudy skies. The subjects include pastoral landscapes, views with ruins, and scenes inspired by his travels. He produced several series of prints, often exploring variations on a theme.

A significant collection of his etchings was published posthumously in Venice in 1730 by Carlo Orsolini, under the title Varia Marci Ricci Pictoris Prestantissimi Experimenta. This publication helped to solidify Ricci's reputation and disseminate his influential landscape style. His etchings influenced subsequent generations of Venetian printmakers, including Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770) and Canaletto, both of whom also made significant contributions to the art of etching. Ricci demonstrated the potential of etching not just for reproduction, but as a medium for original artistic expression in the landscape genre.

Collaborations and Artistic Relationships

Throughout his career, Marco Ricci engaged in collaborations that shaped his work and influenced others. His most significant and enduring partnership was with his uncle, Sebastiano Ricci. From their early work in Florence to major commissions in England, they frequently combined their talents. Typically, Sebastiano, the more established history painter, would execute the main figures, while Marco would contribute the landscape or architectural backgrounds. This division of labor was common practice, allowing specialists to contribute their respective strengths to large decorative projects.

His time in England saw collaboration, and noted rivalry, with Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, particularly on stage designs. While their styles differed – Pellegrini's being lighter and more fluid, closer to the emerging Rococo – their joint efforts were crucial to the visual spectacle of Italian opera in London.

There is also evidence, both stylistic and documentary, suggesting collaborations with Alessandro Magnasco, particularly during Ricci's potential time in Milan or later. In some works attributed to Magnasco, the landscape backgrounds show strong affinities with Ricci's style, leading scholars to propose that Ricci may have painted the settings for Magnasco's distinctive figures. These collaborations highlight the interconnectedness of the artistic community and the ways in which painters with different specializations could work together.

Influence and Legacy

Marco Ricci's impact on eighteenth-century art, particularly in Venice and England, was substantial. He is widely regarded as a foundational figure in the development of Venetian landscape painting, moving beyond the classical models of the seventeenth century towards a more direct, atmospheric, and picturesque approach. His work provided a crucial link between the Baroque tradition and the golden age of Venetian view painting (veduta) represented by Canaletto and Francesco Guardi.

His influence on Canaletto is evident, particularly in Canaletto's early works and his capricci. While Canaletto would develop a more precise, topographically accurate style for his famous views of Venice, Ricci's handling of light and atmosphere, and his interest in the capriccio, were important precedents. Francesco Guardi, whose looser brushwork and more evocative style often focused on the poetic atmosphere of Venice, also shows a clear debt to Ricci, particularly in his landscape drawings and capricci. Some scholars even suggest that Francesco's elder brother, Antonio Guardi (1699–1760), may have produced works directly based on Ricci's compositions.

Other Venetian landscape painters, such as Michele Giovanni Marieschi (1710–1743) and Francesco Zuccarelli (1702–1788), also operated within the tradition that Ricci helped to establish. Zuccarelli, in particular, who also spent time in England, developed a highly popular style of idyllic, pastoral landscapes that owed much to Ricci's groundwork. Ricci's influence extended to Canaletto's nephew, Bernardo Bellotto (1721–1780), whose precise views of European cities carried the Venetian tradition northward.

In England, Ricci's work, disseminated through his paintings brought back by Grand Tourists and through his etchings, contributed to the growing taste for Italianate landscapes and capricci. His paintings were collected by prominent figures like Joseph Smith, the British Consul in Venice, who was also Canaletto's primary agent. Through such channels, Ricci's vision of the Italian landscape continued to resonate long after his death.

Artistic Style Revisited

Marco Ricci's artistic style is a complex synthesis of various influences, adapted into a highly personal vision. Key elements include:

Atmospheric Light: Whether in oil or his favored tempera on parchment, Ricci excelled at capturing the effects of light – the hazy sunshine of the Italian countryside, the dramatic contrasts of a storm, the cool clarity of a winter day.

Painterly Brushwork: His handling is often lively and energetic, particularly in his mature works, suggesting textures and forms rather than delineating them with minute precision. This gives his work a sense of immediacy and vibrancy.

Compositional Skill: Ricci carefully constructed his landscapes and capricci, often using diagonal recessions, framing devices like trees or ruins, and a balance of masses and voids to create dynamic yet harmonious compositions.

Blend of Realism and Idealization: While grounded in observation of nature (influenced by Dutch art), his landscapes often possess an idealized or picturesque quality, in line with Italian traditions. His capricci explicitly blend the real and the imagined.

Versatility in Genre and Medium: Ricci moved comfortably between pure landscape, capriccio, and stage design. He mastered oil painting, tempera, drawing (often in pen and wash), and etching, adapting his technique to the demands of each medium.

Conclusion: A Bridge Between Eras

Marco Ricci occupies a crucial position in the history of Italian art. He revitalized landscape painting in Venice, infusing it with influences from Rome, Naples, and Northern Europe. His mastery of the capriccio established it as a major genre, exploring the evocative power of architectural fantasy. As a pioneer of original etching in Venice, he expanded the expressive possibilities of printmaking. His work forms a vital bridge between the classical landscape tradition of the seventeenth century and the celebrated Venetian vedute and Rococo landscapes that followed. Through his travels, collaborations, and influential style, Marco Ricci left an indelible mark on the art of his time, shaping the course of landscape painting in Italy and beyond, and securing his legacy as a versatile and innovative master of the Venetian School. His paintings, drawings, and etchings continue to be admired for their atmospheric beauty, compositional ingenuity, and lively execution.