Introduction: A Venetian Visionary

The eighteenth century witnessed the final, dazzling flourish of the Venetian Republic's artistic golden age. Amidst the grandeur and spectacle, a generation of painters captured the city's unique beauty, light, and life. Among these was Michele Marieschi (1710–1744), a painter and etcher whose tragically short career nevertheless produced a body of work notable for its vibrancy, dramatic perspective, and unique blend of observed reality and imaginative fancy. Though often discussed in the shadow of his slightly older contemporary, Canaletto, Marieschi possessed a distinct artistic voice, shaped by his early experiences in stage design and his keen eye for the theatrical potential of Venice's urban landscape. His contributions to the genres of the veduta (view painting) and the capriccio (architectural fantasy), as well as his accomplished work as an etcher, secure him a significant place in the annals of Venetian art.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Michele Giovanni Marieschi was born in Venice on December 1, 1710. His father was a woodcarver, suggesting an early exposure to artisanal craftsmanship. More significantly for his later development, his maternal grandfather was Antonio Meneghini, a painter and stage designer. Following his father's early death, the young Marieschi likely received initial guidance from Meneghini, absorbing the principles of perspective and architectural representation inherent in scenography. This foundational experience in creating illusionistic space for the theatre would profoundly inform his later paintings and etchings.

Formal training likely came under Gaspare Diziani, a respected painter from Belluno who was active in Venice and also involved in stage design. Diziani's own style, influenced by masters like Sebastiano Ricci, combined decorative flair with solid draughtsmanship. Under Diziani, Marieschi would have honed his skills in composition and the handling of paint, further developing the spatial awareness first nurtured through his connection to stagecraft. His early career seems to have involved work as a scene painter, possibly travelling briefly in Germany, although his primary sphere of activity remained Venice.

The Impact of Venetian Precursors

Upon establishing himself as an independent artist, Marieschi inevitably engaged with the dominant artistic currents in Venice. He was particularly receptive to the work of two key figures who preceded him in the development of landscape and view painting: Marco Ricci and Luca Carlevaris. Marco Ricci, Sebastiano Ricci's nephew, was a pioneer of the Venetian landscape and the capriccio, often incorporating romantic ruins and atmospheric effects into his compositions. Marieschi absorbed Ricci's interest in imaginative architectural arrangements and evocative moods.

Luca Carlevaris is widely considered the true founder of the Venetian veduta genre as it flourished in the 18th century. His detailed and panoramic views of the city, often populated with numerous small figures documenting festivals and ceremonies, set a precedent for topographical accuracy combined with lively representation. Marieschi learned much from Carlevaris's approach to structuring city views and depicting the bustling life of Venice, though he would soon develop his own, often more dramatic, interpretation of the cityscape.

Venice Observed: The Art of the Veduta

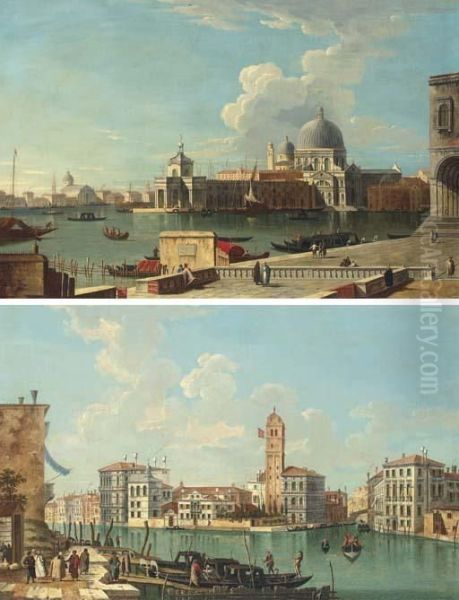

Marieschi quickly gained recognition for his vedute, paintings depicting recognizable views of Venice. While inevitably compared to Canaletto, Marieschi's approach offered a different flavour. His perspectives are often wider, lower, and more dynamic, sometimes employing subtle distortions or exaggerations to enhance the sense of space or drama. He favoured strong contrasts of light and shadow, lending his scenes a certain theatrical energy, perhaps a legacy of his scenographic training. His brushwork could be thicker and more impastoed than Canaletto's meticulous application, contributing to a sense of immediacy and texture, particularly in the rendering of water and architectural surfaces.

He depicted all the famous landmarks that captivated Venetians and foreign visitors alike: the Grand Canal with its procession of palaces, the bustling Piazza San Marco, the iconic Rialto Bridge, the majestic Doge's Palace, and churches such as Santa Maria della Salute and San Giorgio Maggiore. Specific works exemplify his approach: The Isola di San Giorgio Maggiore with the Dogana da Mar (c. 1740) showcases his ability to capture the shimmering light on the lagoon and the grandeur of Palladio's architecture. A Procession in the Piazza San Marco (c. 1740) demonstrates his skill in handling complex compositions filled with lively figures, known as staffage, that animate the architectural setting. The Rialto Bridge with the Palazzo dei Camerlenghi and the Fabbriche Vecchie di Rialto (c. 1737-40) uses a characteristic low viewpoint to emphasize the monumental arch of the bridge.

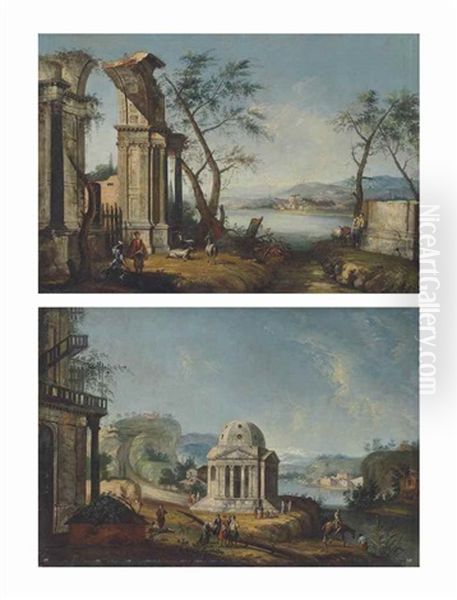

Imagined Worlds: The Capriccio

Alongside his depictions of real locations, Marieschi excelled in the genre of the capriccio. These architectural fantasies allowed for greater imaginative freedom, combining elements of real Venetian buildings with classical ruins, pastoral landscapes, and invented structures. Influenced by Marco Ricci, Marieschi's capricci often possess a romantic, sometimes melancholic, atmosphere. They feature crumbling arches, overgrown stonework, and dramatic skies, creating picturesque scenes that appealed to the era's taste for the sublime and the antique.

Works like Capriccio with Classical Ruins and Bridge and Capriccio with Roman Arch and Encampment, likely from his earlier period, show this clear debt to Ricci and Carlevaris while hinting at his developing style. These paintings are not mere topographical records but poetic evocations, using architecture as a vehicle for mood and invention. The interplay between light and shadow is often pronounced, further enhancing the dramatic and imaginative quality of these scenes. The capriccio offered Marieschi an outlet to explore composition and atmosphere beyond the constraints of strict representation.

Master Etcher: Spreading the Venetian View

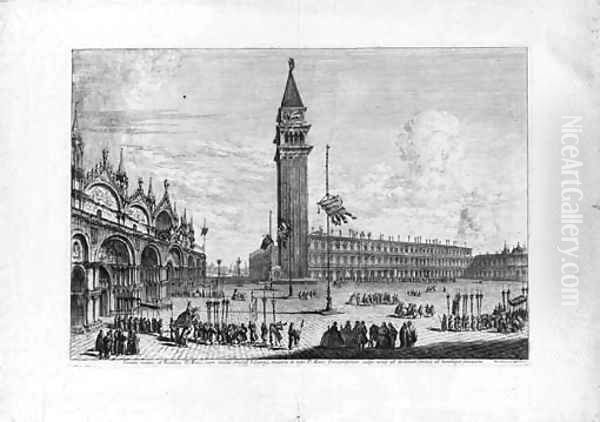

Marieschi was not only a painter but also a highly skilled etcher. His most significant contribution in this medium is the series Magnificentiores selectioresque urbis Venetiarum prospectus (More Magnificent and Select Views of the City of Venice), published in 1741. This collection of 21 plates cemented his reputation and disseminated his vision of Venice to a wider audience, including collectors across Europe. The etchings translate the dynamism of his paintings into line, employing vigorous, calligraphic strokes and bold contrasts to capture the city's architectural splendour and atmospheric effects.

His etchings often exhibit the same dramatic viewpoints and energetic handling found in his paintings. Plate 10, Piazza San Marco with the Church of San Geminiano (the church later demolished under Napoleon), is a fine example, showcasing his ability to render complex architectural detail while maintaining a sense of lively movement through the figures and the play of light across the square. Compared to the precise, linear etchings Antonio Visentini made after Canaletto's paintings, Marieschi's prints often feel more painterly and expressive. This series was crucial in establishing his independent artistic identity and securing his fame beyond Venice.

Distinctive Style and the Scenographic Eye

Marieschi's artistic signature lies in his unique synthesis of observation, imagination, and a distinctly theatrical sensibility. His use of perspective is often bold, employing wide-angle views and sometimes exaggerating spatial recession to create immersive, dynamic compositions. This manipulation of space, creating a sense of spectacle, directly recalls the techniques of stage design. His handling of light is equally dramatic, with strong chiaroscuro effects highlighting architectural forms and creating mood.

His brushwork, often described as "thicker" or more "loaded" than that of some contemporaries, gives his surfaces a tactile quality. Water, in particular, is often rendered with energetic strokes that convey its movement and reflective properties. The figures populating his scenes, the staffage, are typically small but lively, adding touches of colour and narrative interest without dominating the architectural setting. These elements combine to create views of Venice that are both recognizable and imbued with a personal, often dramatic, interpretation.

Navigating the Venetian Art World: Rivals and Contemporaries

The art scene in 18th-century Venice was vibrant but also competitive. Marieschi emerged as arguably the most significant rival to the dominant figure of Canaletto in the field of view painting. While his works sometimes show Canaletto's influence, and indeed were occasionally confused with his, Marieschi maintained his own stylistic identity, characterized by greater dynamism and a more overtly painterly approach. This rivalry spurred both artists, contributing to the richness of the Venetian veduta tradition.

Marieschi also interacted with other leading artists. He collaborated with the elder Luca Carlevaris on at least one occasion, painting figures in a view of the Scuola Grande di San Marco. He was aware of the work of other major figures shaping Venetian art, such as the great decorative painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, the chronicler of Venetian daily life Pietro Longhi, and the brilliant pastellist Rosalba Carriera. He also worked alongside Bernardo Bellotto, Canaletto's talented nephew, who himself became a renowned view painter. Marieschi's workshop played a role in this artistic ecosystem, training assistants and disseminating his style.

Patronage, Workshop, and Influence

Like Canaletto, Marieschi found patrons among both the local nobility and the increasing number of foreign visitors undertaking the Grand Tour. A particularly important collector of his work was Field Marshal Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg, a German mercenary general in Venetian service, whose extensive art collection included numerous paintings by Marieschi. This patronage indicates Marieschi's appeal to sophisticated international tastes.

His workshop was an active enterprise. His most notable pupil and assistant was Francesco Albotto. After Marieschi's untimely death, Albotto inherited the workshop and continued to produce paintings very much in his master's style. This has sometimes led to difficulties in attribution, as Albotto's works can closely mimic Marieschi's compositions and handling. Marieschi's influence also extended to Francesco Guardi, who, along with his brother Gian Antonio Guardi, likely knew Marieschi's work well. While Guardi developed a much looser, more atmospheric style later in his career, his earlier vedute sometimes show an affinity with Marieschi's dynamic compositions and perspectives.

Untimely Death and Enduring Legacy

Michele Marieschi's promising career was cut tragically short. He died in Venice on January 18, 1744 (though some earlier sources cited 1743), at the young age of 33. His death left his workshop in the hands of Albotto and curtailed what might have been a longer and even more influential trajectory. Despite the brevity of his independent working life—spanning little more than a decade—he produced a substantial and significant body of work.

His legacy rests on his distinctive contribution to Venetian view painting and the capriccio. He offered a compelling alternative to Canaletto's crystalline precision, infusing his scenes with a greater sense of drama, movement, and painterly texture. His mastery of etching further amplified his impact, spreading his vision of Venice across Europe. He remains a key figure for understanding the diversity and richness of 18th-century Venetian art, representing a unique blend of topographical accuracy, imaginative invention, and theatrical flair.

Reassessment and Recognition in Art History

For a considerable period, Marieschi's reputation was somewhat obscured. His stylistic similarities to Canaletto, coupled with the continuation of his style by Albotto, led to frequent misattributions and an underestimation of his originality. He was sometimes seen merely as an imitator or a lesser figure within the Venetian school. However, twentieth-century scholarship began a process of re-evaluation, distinguishing his hand more clearly from that of his contemporaries and followers.

Art historians now recognize Marieschi's unique strengths: his innovative use of perspective, his dramatic handling of light and shadow, his skill as an etcher, and the influence of his scenographic background on his distinctive compositional choices. Exhibitions dedicated to his work and focused scholarly studies have highlighted his technical abilities and his specific contribution to the veduta and capriccio genres. While Canaletto may remain the most famous name in Venetian view painting, Marieschi is now firmly established as an important and original master in his own right, admired for the energy and individuality of his artistic vision.

Conclusion: A Unique Venetian Perspective

Michele Marieschi stands as a vital figure in the luminous landscape of 18th-century Venetian art. In his brief but brilliant career, he forged a distinctive style that captured both the magnificent reality and the imaginative potential of his native city. Influenced by stage design and the work of precursors like Carlevaris and Ricci, yet fiercely individual, he created paintings and etchings characterized by dynamic perspectives, dramatic light, and energetic handling. As both a vedutista and a master of the capriccio, he navigated the space between observation and invention with remarkable skill. Though his life was short, his works continue to offer a compelling and theatrical vision of Venice, securing his place as a significant master of the Italian Settecento.