Giovanni Giacometti stands as a pivotal figure in Swiss art history, a painter whose canvases radiate with the intense light and vibrant hues of the Alpine landscapes he called home. Born in 1868 and active until his death in 1933, he navigated the complex currents of late 19th and early 20th-century European art, forging a unique style rooted in Post-Impressionism yet distinctly his own. He was not only a significant artist in his own right but also the patriarch of an extraordinary artistic dynasty, most famously as the father of the sculptor Alberto Giacometti. His work serves as a crucial bridge, mediating the innovations of French and Italian modernism for a Swiss audience and context.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in the Grisons

Giovanni Giacometti was born in Stampa, a village nestled in the Val Bregaglia in the Swiss canton of Grisons. This mountainous region, with its dramatic light, changing seasons, and rugged beauty, would remain a constant source of inspiration throughout his life. From a young age, he displayed a clear aptitude for drawing and painting, an inclination perhaps nurtured by the environment and the legacy of artistic activity in the region. The unique atmosphere and luminous quality of the Alpine air seem to have imprinted themselves on his artistic sensibility early on.

His formal artistic education began not in Switzerland, but in Germany. In 1886, seeking broader horizons, the young Giacometti traveled to Munich. There, he enrolled to study decorative arts, a field that perhaps honed his sense of composition and color harmony. Munich at this time was a significant artistic center, though perhaps more conservative than Paris. It was here, however, that a crucial encounter took place: he met Cuno Amiet, another aspiring Swiss artist. This meeting marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship and artistic dialogue that would profoundly shape both their careers and the course of modern Swiss painting.

Formative Years: Munich and Paris

The time in Munich provided foundational training, but the true epicenter of artistic innovation was Paris. Following his studies in Germany, Giacometti, along with Amiet, made the pilgrimage to the French capital. He continued his studies, enrolling at the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school famous for attracting international students and offering a more liberal alternative to the official École des Beaux-Arts. Here, he would have been immersed in the vibrant, and often contentious, Parisian art scene.

Paris in the late 1880s and early 1890s was a crucible of artistic experimentation. Impressionism, once revolutionary, was becoming established, while new movements were rapidly emerging. Giacometti would have encountered the works of Impressionist masters like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro, absorbing their lessons on capturing fleeting light and atmospheric effects. More importantly, he was exposed to the burgeoning Post-Impressionist trends: the structural concerns of Paul Cézanne, the expressive color of Vincent van Gogh, and the pointillist technique of Georges Seurat. The bold colors and simplified forms of the Pont-Aven school, led by Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard, also left a significant mark, influencing his later embrace of strong chromatic statements.

The Defining Influence of Giovanni Segantini

While Paris provided exposure to a wide range of influences, a more personal and profound mentorship came from the Italian painter Giovanni Segantini. Giacometti likely met Segantini through Cuno Amiet. Segantini, a leading figure of Italian Divisionism (a variant of Pointillism), had moved to the Engadine valley, close to Giacometti's native Stampa, settling in Maloja in 1894. This proximity facilitated a close relationship. Segantini became a mentor and a major source of inspiration, particularly regarding the technique of applying color and capturing the intense luminosity of the high Alps.

Segantini's Divisionist technique involved applying paint in small dots or strokes of pure color, allowing the viewer's eye to blend them optically. This method aimed to achieve greater luminosity and vibrancy than traditional color mixing on the palette. Giacometti eagerly adopted this technique, finding it perfectly suited to rendering the clear, bright light and distinct color zones of the mountain landscapes he loved. However, while Segantini often imbued his Alpine scenes with symbolic or allegorical meaning, Giacometti's approach remained more focused on the direct, sensory experience of light, color, and atmosphere. His use of Divisionism often resulted in works that felt warmer and more immediate than Segantini's sometimes starker, more monumental canvases.

Friendship and Collaboration with Cuno Amiet

The friendship forged with Cuno Amiet in Munich remained a cornerstone of Giacometti's personal and artistic life. They shared studios, traveled together, and constantly exchanged ideas. Their shared experiences in Paris, their mutual admiration for artists like Van Gogh and Gauguin, and their joint exploration of color theory created a powerful synergy. Together, Giacometti and Amiet are often credited as the pioneers of modern colorism in Swiss painting.

They both returned to Switzerland, bringing with them the lessons learned abroad. While Giacometti remained deeply connected to the Grisons, Amiet settled near Solothurn and developed connections with German Expressionist groups like Die Brücke. Despite their slightly different paths and networks, their artistic dialogue continued. They exhibited together and maintained a close bond, representing a vital force in pushing Swiss art beyond the confines of 19th-century academicism and naturalism. Amiet's bolder, sometimes near-Fauvist use of color may have encouraged Giacometti's own chromatic explorations, while Giacometti's grounding in the Divisionist technique provided a structured approach to capturing light.

Ferdinand Hodler and the Swiss Context

Another significant figure in the Swiss art scene during Giacometti's formative years was Ferdinand Hodler. Giacometti studied under Hodler, absorbing lessons in capturing form and perhaps being influenced by Hodler's emphasis on line and monumental composition, characteristic of his Symbolist style known as Parallelism. Hodler was arguably the most dominant Swiss artist of the era, achieving international recognition.

While Giacometti respected Hodler, his own artistic temperament leaned more towards the color and light explorations of French Post-Impressionism and the intimacy of landscape and domestic scenes, rather than Hodler's often heroic, symbolic, or historical subjects. Giacometti’s engagement with light and broken color contrasts with Hodler’s use of strong outlines and clearly defined planes of color. Nonetheless, Hodler's powerful presence underscored the burgeoning sense of a distinct modern Swiss art identity, a context within which Giacometti developed his own unique voice. Other Swiss contemporaries, like the Paris-based Félix Vallotton, associated with the Nabis, also contributed to the diverse landscape of Swiss modernism, though Vallotton's style was markedly different with its flat planes and sharp outlines.

Forging a Personal Style: Light, Color, and Place

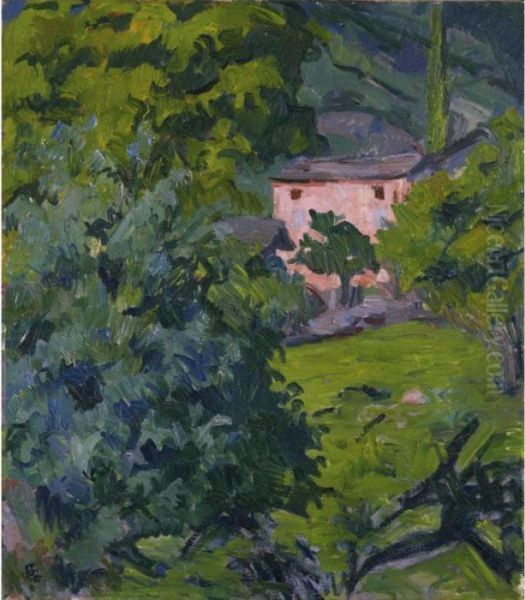

Synthesizing the diverse influences he encountered – the Divisionism of Segantini, the color experiments of Van Gogh and Gauguin, the atmospheric concerns of Impressionism, and the structural lessons perhaps gleaned from Hodler – Giovanni Giacometti forged a highly personal style. His mature work is characterized by a vibrant palette, often applied with distinct, energetic brushstrokes that retain a Divisionist separation of color while conveying texture and form. He became a master at capturing the specific qualities of Alpine light – the sharp clarity of winter sun on snow, the hazy warmth of summer afternoons, the cool blues of twilight.

His connection to the Pont-Aven school is evident in his willingness to use color expressively and decoratively, moving beyond purely naturalistic representation. The bright yellows, intense blues, vibrant greens, and warm oranges that dominate his canvases are chosen as much for their emotional impact and compositional harmony as for their descriptive accuracy. This approach, combined with the Divisionist technique, allowed him to create paintings that shimmer with light and life. His style proved remarkably adaptable to the landscapes of the Grisons, making the familiar scenes of his homeland appear fresh and intensely alive.

Subject Matter: The Alpine Landscape

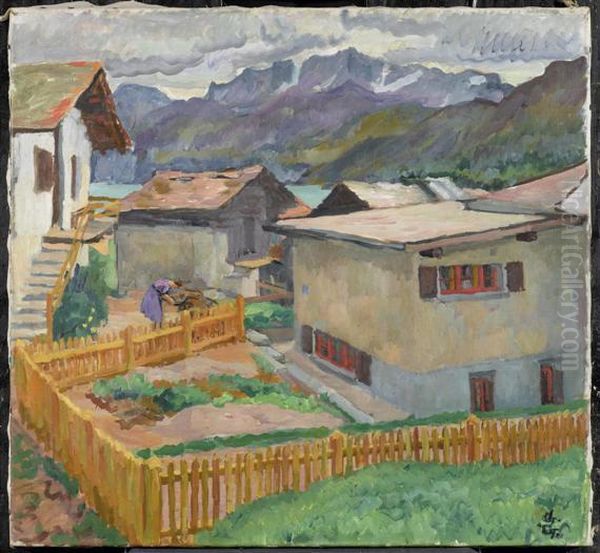

The landscape of the Val Bregaglia and the nearby Engadine valley remained Giacometti's most enduring subject. He painted his surroundings relentlessly, capturing the changing seasons, the play of light on mountains, fields, and forests, and the simple structures of rural life. Works depicting snow-covered slopes bathed in winter sunlight, autumnal forests ablaze with color, or panoramic views under vast Alpine skies are central to his oeuvre.

Unlike Segantini's often dramatic or symbolic mountain vistas, Giacometti's landscapes frequently possess a sense of intimacy and familiarity. He painted the views from his window, the nearby village of Maloja, the Piz Duan mountain, and the winding roads and rivers of the valley. His focus was often on the interaction of light and color within these scenes, using broken brushwork to convey the shimmer of sunlight on snow, the texture of foliage, or the reflections in water. Titles like Winter Sun near Maloja or View of Capolago point to this deep engagement with specific places and atmospheric conditions.

Subject Matter: Intimate Portraits and Family Life

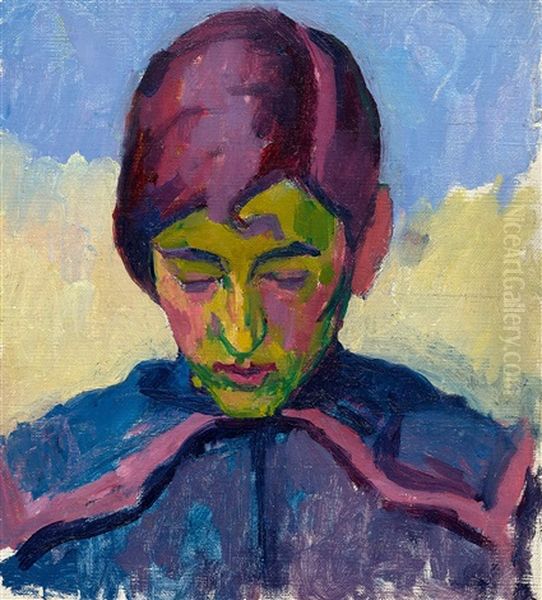

Alongside landscape, Giacometti dedicated a significant portion of his work to portraiture and scenes of domestic life. After his marriage to Annetta Stampa in 1900, his wife and their four children – Alberto, Diego, Ottilia (who died young), and Bruno – became frequent subjects. These works offer a warm and intimate glimpse into the artist's family circle. He painted Annetta reading, sewing, or caring for the children; he captured his sons drawing, playing, or simply posing.

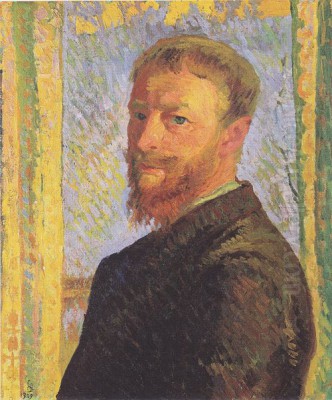

These portraits and genre scenes are rendered with the same vibrant color and attention to light that characterize his landscapes. Works like The Lamp (Die Lampe), depicting his family gathered around a table under the warm glow of lamplight, showcase his ability to handle interior light sources and create a sense of enclosed warmth and familial connection. Other notable examples include Maternité (Motherhood) and paintings specifically titled after his children, such as Annetta und Alberto or Diego and Ottilia. These works are not just family records; they are sensitive studies of human presence, rendered with psychological insight and painterly richness. His numerous Self-Portraits also reveal an ongoing exploration of identity through his characteristic style.

Recognition and Role in Swiss Art

Giovanni Giacometti achieved considerable recognition within Switzerland during his lifetime. He exhibited regularly, including important solo shows at the Kunsthaus Zürich in 1912 and the Kunstmuseum Bern in 1920. His work was acquired by major Swiss museums, including the Swiss Federal Art Museum, confirming his status as a leading figure in national art. He was seen as a vital link between international artistic developments and the Swiss scene, translating modern French and Italian ideas into a visual language that resonated with his homeland.

His commitment to depicting the specific light and landscape of the Grisons, combined with his modern technique, helped to shape a distinctly Swiss form of Post-Impressionism. He demonstrated that avant-garde techniques could be powerfully applied to local subjects, enriching the national artistic identity. His influence extended not only through his paintings but also through his role within the artistic community and, significantly, within his own family.

The Giacometti Dynasty: An Artistic Legacy

Giovanni Giacometti was the head of a remarkable artistic family. His passion for art created an environment where creativity was nurtured and encouraged. His influence is most evident in his eldest son, Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966), who would become one of the 20th century's most important sculptors and painters. Alberto's early works clearly show his father's stylistic influence, particularly in painting, before he developed his own unique, existentialist vision after studying in Paris, notably under Antoine Bourdelle, and engaging with Surrealism and figures like Jean-Paul Sartre (though Sartre was more directly associated with Alberto's circle later in Paris).

Giovanni's second son, Diego Giacometti (1902-1985), became a renowned furniture designer and sculptor, often collaborating closely with Alberto and developing his own distinctive style in bronze furniture and objects. The youngest son, Bruno Giacometti (1907-2012), pursued a successful career as an architect, contributing significantly to modern Swiss architecture. Furthermore, Giovanni's second cousin, Augusto Giacometti (1877-1947), was also a prominent artist, known for his pioneering work in abstract painting and stained glass, following a path influenced more by Symbolism and Art Nouveau. The Giacometti name thus became synonymous with artistic excellence across multiple disciplines, a legacy rooted in the creative atmosphere fostered by Giovanni.

Later Years and Enduring Importance

Giovanni Giacometti continued to paint actively throughout his later years, remaining dedicated to capturing the landscapes and life around Stampa and Maloja. His style, while established, continued to evolve subtly, always prioritizing the expression of light through color. He faced periods of financial difficulty, particularly earlier in his career, which sometimes forced him to seek work elsewhere, including brief stints working on murals in Italy (Rome and Naples), but he always returned to his native valley.

He passed away in 1933 at a sanatorium in Glion, above Montreux, leaving behind a substantial body of work that continues to be celebrated. Retrospectives, such as the major exhibition shared between the Kunstmuseum Bern and the Bündner Kunstmuseum Chur in 2020, reaffirm his importance. Giovanni Giacometti's legacy lies in his mastery of color and light, his sensitive depiction of the Swiss Alpine world, his crucial role in bringing modernism to Switzerland, and his position as the founder of an unparalleled artistic dynasty. His paintings offer a luminous vision of his time and place, infused with both international artistic currents and a deep, personal connection to his roots.

Conclusion: A Luminous Vision

Giovanni Giacometti occupies a unique and vital place in the history of modern art. As a Swiss Post-Impressionist, he skillfully navigated the complex artistic landscape of his time, absorbing influences from Segantini's Divisionism, French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism (Monet, Van Gogh, Gauguin), and the Swiss context defined by figures like Hodler, while always maintaining his own distinct voice. His lifelong friendship with Cuno Amiet further enriched his development and cemented their joint role as pioneers of Swiss colorism. His dedication to capturing the intense light and specific atmosphere of the Val Bregaglia and Engadine resulted in a body of work that glows with chromatic vibrancy and profound sensitivity to place. Equally significant are his intimate portrayals of family life, which reveal warmth and psychological depth. As the father of Alberto, Diego, and Bruno, and cousin of Augusto, he stands at the head of an extraordinary artistic lineage. More than just a precursor or a relative, Giovanni Giacometti was a master in his own right, an artist whose luminous canvases continue to resonate with viewers today, offering a powerful and enduring vision of the Alpine world.