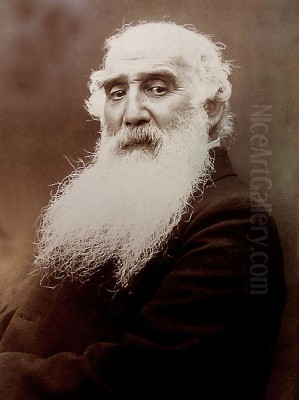

Introduction: A Pivotal Figure in Art History

Camille Pissarro stands as one of the most influential and respected figures in the history of modern art. Spanning a career that bridged Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Pissarro (1830-1903) was not only a prolific painter but also a crucial mentor and organizing force within the avant-garde movements of late 19th-century France. Born in the Caribbean, he brought a unique perspective to the Parisian art world. He holds the singular distinction of being the only artist to have exhibited his work in all eight Impressionist exhibitions, held between 1874 and 1886. Often referred to as the "Father of Impressionism," his dedication, innovative spirit, and supportive nature profoundly impacted his contemporaries and subsequent generations of artists.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Two Worlds

Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro was born on July 10, 1830, on the island of St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies (now the U.S. Virgin Islands). His background was notably diverse: his father, Frederick Pissarro, was a merchant of Portuguese Sephardic Jewish descent whose family had roots tracing back through Bordeaux, France, and potentially Portugal, possibly fleeing persecution. His mother, Rachel Manzano-Pomié, was a Creole woman born in the Dominican Republic, also of Jewish heritage but perhaps with mixed ancestry common in the Caribbean. This multicultural upbringing in the bustling port town of Charlotte Amalie likely shaped his worldview.

Pissarro's family was part of the island's merchant class, with his father running a general store. From a young age, Camille displayed a keen interest in drawing and painting, often sketching the vibrant life and landscapes around the harbor. However, his family initially intended for him to follow a commercial path. At the age of twelve, he was sent to a boarding school near Paris, the Savary Academy in Passy. There, the headmaster, Monsieur Savary, recognized and encouraged his artistic talent, advising him to draw from nature upon his return to St. Thomas.

He returned five years later, dutifully working as a clerk in his father's business for the next five years. Yet, his passion for art never waned. He spent every spare moment sketching the local scenery, the docks, and the people of St. Thomas. A pivotal encounter occurred with the Danish painter Fritz Melbye, who visited the island. Melbye became a friend and mentor, encouraging Pissarro's artistic ambitions. In 1852, against his family's wishes, the 21-year-old Pissarro abandoned his clerkship and sailed with Melbye to Caracas, Venezuela, where they shared a studio for two years, dedicating themselves entirely to painting. This act marked his definitive break from commerce and his commitment to an artistic life.

Arrival in Paris and the Seeds of Impressionism

In 1855, seeking formal training and immersion in the European art world, Pissarro moved to Paris, the epicenter of artistic innovation and tradition. He received some financial support from his parents, who had also relocated to Paris by then. He enrolled in various private studios, including the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts and the more informal Académie Suisse. It was at the Académie Suisse that he began to connect with other young artists who shared his dissatisfaction with the rigid academic standards promoted by the official Salon.

During these formative years in Paris, Pissarro sought guidance from established artists. He was particularly drawn to the work of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, a leading figure of the Barbizon School known for his sensitive landscapes painted outdoors (en plein air). Pissarro briefly received advice from Corot and admired his ability to capture light and atmosphere. He was also influenced by the realism of Gustave Courbet, whose unidealized depictions of peasant life and bold technique challenged academic conventions. Other early influences included Jean-François Millet, known for his dignified portrayals of rural labor.

Pissarro began submitting works to the official Paris Salon, achieving his first acceptance in 1859. His early paintings, primarily landscapes around Paris and its environs like Montmorency and La Varenne, showed the influence of Corot but already hinted at a developing personal style characterized by a freer application of paint and a focus on the effects of light. He was beginning to move away from the darker palettes of the Barbizon school towards a brighter, more vibrant approach.

Forging the Impressionist Movement

The 1860s were a crucial decade for Pissarro and the future Impressionists. At the Académie Suisse and later at the Café Guerbois, Pissarro became a central figure in a circle of rebellious young artists that included Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Frédéric Bazille, and later, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, and Paul Cézanne. They shared a common desire to paint modern life and landscape directly from observation, capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere with broken brushwork and a brighter palette, rejecting the historical, mythological, or overly polished subjects favored by the Salon.

Pissarro, being slightly older and possessing a thoughtful, encouraging temperament, naturally assumed a role as a mentor and unifying presence within this group. His commitment to cooperative action was instrumental. As the group faced repeated rejection from the official Salon, the idea of organizing their own independent exhibitions gained traction. Pissarro was a key proponent and organizer of this radical venture.

In 1874, the group, calling themselves the "Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs" (Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers), held their first independent exhibition at the former studio of the photographer Nadar. This exhibition, which included Pissarro's seminal work Hoarfrost (Gelée Blanche, 1873), was met with public ridicule and critical scorn. It was from a mocking review of Monet's Impression, Sunrise that the term "Impressionism" was coined, initially as an insult, but later adopted by the artists themselves. Pissarro remained steadfast, participating loyally in all eight Impressionist exhibitions between 1874 and 1886, a testament to his unwavering belief in their collective vision and his dedication to artistic independence.

Pissarro's Impressionist Style: Light, Landscape, and Life

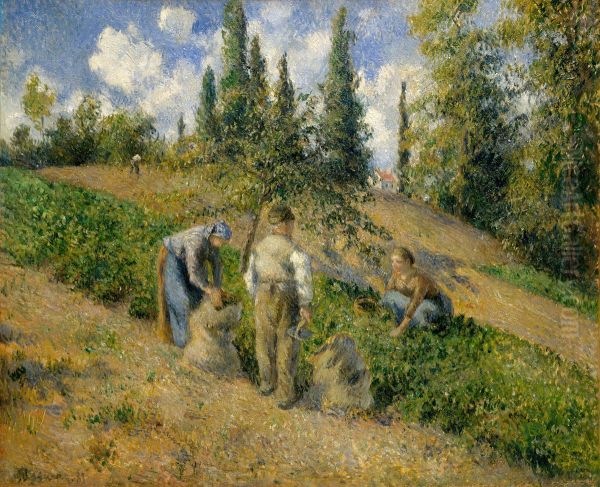

During the height of the Impressionist period in the 1870s, Pissarro primarily lived and worked in rural areas outside Paris, notably in Louveciennes and then Pontoise. These locations provided him with the landscapes that became central to his art. His paintings from this era exemplify the core principles of Impressionism. He worked extensively outdoors (en plein air), directly observing the changing conditions of light and weather.

His brushwork became looser and more visible, using dabs and strokes of pure color placed side-by-side, allowing the viewer's eye to blend them optically. This technique aimed to capture the vibrancy and immediacy of visual perception. Works like The Road to Louveciennes (1872) or Kitchen Garden, Trees in Flower (1877) showcase his mastery of rendering sunlight filtering through leaves, the texture of cultivated earth, and the atmospheric haze of different seasons.

Unlike some Impressionists who focused more purely on landscape or cityscape, Pissarro consistently integrated human figures into his scenes, particularly peasants and agricultural workers. His depictions were neither overly sentimentalized nor harshly critical; rather, they presented rural life with a sense of quiet dignity and authenticity. Paintings like Hoarfrost (1873), showing a lone peasant working in a frost-covered field under a pale winter sun, convey both the beauty of the landscape and the reality of rural labor. This focus reflected his deep connection to the countryside and his burgeoning social conscience.

Experimentation with Neo-Impressionism

In the mid-1880s, Impressionism began to fragment as artists pursued individual directions. Pissarro, ever open to new ideas, became fascinated by the more scientific approach to color and light being developed by younger artists Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. This new style, known as Neo-Impressionism or Pointillism (also Divisionism), involved applying paint in small, distinct dots or points of pure color, based on optical theories suggesting these dots would blend in the viewer's eye to create more luminous and stable images than the looser Impressionist brushwork.

Around 1885, Pissarro embraced this demanding technique. He collaborated closely with Seurat and Signac and exhibited Neo-Impressionist works, such as Apple Harvest (1888), alongside them, notably at the final Impressionist exhibition in 1886, which caused some friction with Impressionist colleagues like Monet and Renoir who disliked the new style. Pissarro's Pointillist phase lasted for about four or five years.

While he produced significant works in this style, Pissarro eventually found the meticulous, systematic application of dots too restrictive and slow, feeling it hampered his ability to capture the spontaneity of nature and his own sensations. Around 1890, he abandoned strict Pointillism, though the experience arguably enriched his palette and perhaps reinforced his structural sense. He returned to a freer, more fluid style that synthesized his Impressionist foundations with the heightened color awareness gained from his Neo-Impressionist experiments.

Subject Matter: Rural Harmony and Urban Dynamism

Throughout his career, Pissarro's choice of subject matter remained deeply connected to his lived experience and his philosophical outlook. For decades, his primary focus was the French countryside. He painted the rolling hills, fields, orchards, and villages of the Île-de-France region, particularly around Pontoise and later Éragny-sur-Epte, where he settled permanently in 1884. His landscapes often depict scenes of agricultural life: farmers plowing fields, women tending gardens, villagers gathering at markets like in Le Marché de la Campagne (The Country Market, 1882).

These rural scenes were imbued with a sense of harmony and tranquility, yet they also reflected Pissarro's social and political views. He held strong anarchist beliefs, sympathizing with the working class and envisioning a society based on mutual aid and freedom from oppressive structures. His depictions of peasants are often seen as embodying ideals of simple, productive labor in communion with nature, a subtle counterpoint to the industrialization and social hierarchies of the time. His anarchist views sometimes put him at odds with the authorities and society; he even spent time in exile in Belgium due to his political affiliations.

In the last decade of his life, suffering from a recurring eye infection that made working outdoors difficult, Pissarro turned increasingly to urban landscapes. Renting rooms in Paris, Rouen, Dieppe, and Le Havre, he painted series of city views from windows overlooking bustling boulevards, bridges, and harbors. His famous series depicting Boulevard Montmartre (1897) and Avenue de l'Opéra (1898) capture the energy and atmosphere of the modern city at different times of day and in various weather conditions – morning fog, afternoon sun, rainy evenings, festive nights. These late works demonstrate his continued fascination with light and atmosphere, now applied to the dynamic spectacle of urban life.

The Mentor: "Father of Painters"

Pissarro's influence extended far beyond his own canvases. His wisdom, generosity, and unwavering support for fellow artists earned him immense respect and the affectionate title "le père Pissarro" (Father Pissarro). He was a natural teacher and mentor, always willing to offer advice, encouragement, and practical help to younger or struggling artists, regardless of their style.

His relationship with Paul Cézanne is particularly significant. During the 1870s, Cézanne worked closely alongside Pissarro in Pontoise. Pissarro encouraged Cézanne to lighten his palette, paint outdoors, and adopt Impressionist techniques. Cézanne later acknowledged his debt, famously stating, "As for Pissarro, he was a father to me. A man to consult and something like the good Lord." While Cézanne eventually forged his own unique path towards Post-Impressionism and Cubism, his time with Pissarro was crucial in his development.

Pissarro also played a supportive role for Paul Gauguin in his early years as a painter, before Gauguin developed his Synthetist style. He offered guidance to Vincent van Gogh through correspondence via Vincent's brother Theo. Even artists of later generations, like Henri Matisse, acknowledged Pissarro's importance as a foundational figure. His open-mindedness, lack of artistic dogma, and genuine kindness made him a central, stabilizing force in the often-turbulent Parisian art world. He truly embodied the spirit of collaboration and mutual support that he advocated through his anarchist principles.

Personal Life, Character, and Principles

Pissarro's personal life was marked by commitment and simplicity, though not without challenges. Around 1860, he began a relationship with Julie Vellay, who was working as his mother's maid. This relationship defied bourgeois conventions and initially met with disapproval from his parents. They lived together for many years and had several children before finally marrying officially in London in 1871, during their refuge there from the Franco-Prussian War.

The marriage was enduring, lasting until Pissarro's death. They had eight children in total, although sadly, one died at birth and another, Minette, died at age nine. Several of their sons, including Lucien, Georges Henri (Manzana), Félix, and Ludovic-Rodo, also became painters, carrying on the family's artistic legacy. Despite his growing artistic reputation, Pissarro often struggled financially throughout his life, working tirelessly to support his large family.

Contemporaries described Pissarro as modest, patient, kind-hearted, and principled. His anarchist beliefs were deeply held, informing his art and his interactions. He believed in individual liberty, social equality, and the importance of community. His famous quote, "Blessed are they who see beautiful things in humble places where other people see nothing," reflects both his artistic focus on everyday life and his philosophical outlook. Anecdotes, like one involving a student named Marie de Bellio possibly sharing a cream recipe, add small humanizing touches, though his primary relationships centered around his family and his wide circle of artist friends.

Later Years, Legacy, and Collections

In 1884, Pissarro bought a house in Éragny-sur-Epte, a village in Normandy, where he would live for the rest of his life, though he frequently traveled to paint elsewhere, especially in his later years for his city series. His work continued to evolve, integrating lessons from his Neo-Impressionist phase into a mature style characterized by vibrant color, textured brushwork, and a profound sense of light and place.

Although he never achieved the commercial success of contemporaries like Monet or Renoir during his lifetime, his reputation grew steadily. By the 1890s, his work was being handled by the influential dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who organized successful solo exhibitions for him. His importance as a key figure in Impressionism and a precursor to Post-Impressionism became increasingly recognized by critics and collectors.

Camille Pissarro died of sepsis in Paris on November 13, 1903, at the age of 73. He left behind a vast oeuvre of paintings, drawings, and prints, and an indelible mark on the course of modern art. His legacy lies not only in his beautiful and innovative artwork but also in his crucial role as a catalyst for Impressionism, his mentorship of other great artists, and his unwavering commitment to artistic freedom and his personal principles.

Today, Pissarro's works are held in the collections of major museums worldwide. The Musée d'Orsay in Paris holds a significant collection, including works like The Harvest and Young Peasant Woman Drinking Her Café au Lait. Other prominent institutions featuring his art include the Metropolitan Museum of Art and MoMA in New York, the National Gallery in Washington D.C., the National Gallery in London, the Tate Britain, the Kunstmuseum Basel in Switzerland, and the Museum Barberini in Potsdam, Germany. A museum dedicated to him and his sons, the Musée Camille Pissarro, exists in Pontoise, the town where he spent many productive years. Recent exhibitions, such as those in Basel (2021-2022) and Potsdam (2024-2025), continue to explore his multifaceted contributions and affirm his enduring relevance.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Camille Pissarro remains a towering figure in art history, a quiet revolutionary whose dedication and vision helped shape the course of modern painting. As a founding member and the most consistent participant in the Impressionist movement, he championed the depiction of contemporary life and the direct observation of nature. His exploration of Neo-Impressionism demonstrated his lifelong openness to experimentation. Through his focus on rural landscapes, peasant life, and later, dynamic cityscapes, he infused his art with both aesthetic beauty and a subtle social consciousness. Perhaps most importantly, his role as a mentor and unifying figure fostered a spirit of collaboration and innovation among his peers, influencing giants like Cézanne, Gauguin, and Seurat. Pissarro's legacy is one of artistic integrity, humanism, and a profound ability to find and convey beauty in the everyday world.