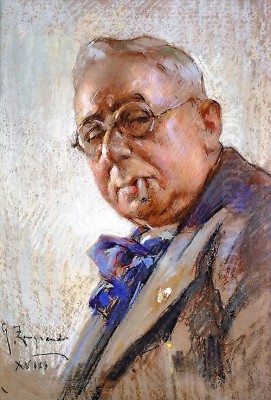

Giovanni Zangrando stands as a figure representing a specific current within Italian art during a period of significant transition, spanning the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born in Treviso in 1867 and passing away in 1941, Zangrando dedicated his life to painting, primarily working with oil paints to capture the world around him. His career unfolded against the backdrop of Italy's rich artistic heritage while also touching upon the personal and societal upheavals of his time, including the trauma of war. Though perhaps not as globally renowned as some of his contemporaries, his work offers valuable insights into regional Italian art and the enduring power of traditional techniques blended with personal expression.

Origins in the Veneto Region

Zangrando hailed from Treviso, a city located in the Veneto region of northeastern Italy. This geographical placement is significant, as Veneto, and particularly its capital Venice, boasts one of the most influential artistic legacies in the world. For centuries, the Venetian School of painting, famed for its mastery of color and light, produced titans like Titian, Tintoretto, and Paolo Veronese. Later, view painters like Canaletto captured the city's unique atmosphere with meticulous detail. Growing up in this environment, even if largely self-taught as some accounts suggest, Zangrando would have inevitably absorbed the visual culture and artistic standards set by these historical masters.

The late nineteenth century in Italy also saw the rise of movements seeking new forms of expression. The Macchiaioli in Tuscany, including artists like Giovanni Fattori, Telemaco Signorini, and Silvestro Lega, experimented with capturing light and form through patches ('macchie') of color, embracing realism and everyday subjects. While Zangrando's documented style seems more aligned with detailed realism than the looser Macchiaioli approach, the broader national context was one of artists grappling with academic traditions and exploring new ways to depict modern life and landscape. Zangrando's work appears to fit within this milieu, focusing on careful observation and skilled execution in oil.

Artistic Style and Technique

Giovanni Zangrando's primary medium was oil painting, a technique he employed with considerable skill. His style is often characterized as belonging to the broader category of nineteenth-century Italian painting, which frequently emphasized realism, attention to detail, and competent draughtsmanship. Sources mention his work exhibiting a fine technique and a dedication to capturing specifics, suggesting a departure from the looser, more light-focused experiments of French Impressionism, which was developing concurrently.

One specific work, Passeggio Sant’Andrea, dated 1898, exemplifies his approach. Created using oil on board and measuring 97.5 x 90 cm, this painting likely depicts a scene with careful rendering, typical of genre or landscape scenes popular during that era. The choice of oil on board itself is a traditional practice. His overall style has been described as combining elements of classicism and romanticism, resulting in a soft and delicate brushwork that nonetheless conveys a strong sense of form and place.

Further insights into his style come from descriptions of a work titled Bison. This painting is noted for its精湛 (exquisite/masterful) handling of details, particularly in the rendering of tree foliage and architectural elements. The mention of classical and Gothic architectural features within this work suggests Zangrando had an interest in historical structures and possessed the technical ability to depict their complexities accurately. This focus aligns with a strand of late 19th-century art that valued historical motifs and precise representation.

Representative Works

Several works are specifically associated with Giovanni Zangrando, offering glimpses into his thematic interests and artistic output. Among his known paintings are Isola del Mare (Island of the Sea) and Paesaggio della chiesa di Cadore (Landscape of the Church of Cadore). These titles strongly suggest a focus on landscape painting, a genre deeply rooted in the Italian tradition, particularly the depiction of the varied terrains and specific locales of the peninsula. Isola del Mare evokes coastal or island scenery, perhaps reflecting the proximity of Treviso to the Adriatic, while the Cadore landscape points to the mountainous regions north of Venice.

The previously mentioned Passeggio Sant’Andrea (1898) likely represents a cityscape or a scene of daily life, perhaps depicting people strolling along a specific location in Trieste, as suggested by its inclusion in a 1984 exhibition catalog from that city. Another named work is Cortile (Courtyard), further indicating an interest in architectural spaces and potentially the interplay of light and shadow within enclosed urban or domestic settings. The painting Bison, noted for its detailed execution, adds another dimension, though the subject matter (an animal, or perhaps a place named Bison?) remains slightly ambiguous without visual confirmation. Collectively, these titles point towards an artist engaged with landscape, cityscape, architecture, and potentially genre scenes.

Themes of Landscape and Place

The recurring theme in Zangrando's known works appears to be the depiction of place, whether natural landscapes, architectural settings, or urban environments. His paintings like Isola del Mare and Paesaggio della chiesa di Cadore situate him firmly within the tradition of landscape painting. Artists in the Veneto region have long been inspired by the unique interplay of water, land, and architecture, from the Venetian lagoon to the foothills of the Alps. Zangrando seems to have continued this tradition, focusing his observational skills on capturing the specific character of these locations.

His work Passeggio Sant’Andrea and Cortile suggest an engagement with the built environment as well. Nineteenth-century Italian art often explored scenes of contemporary life, including urban settings. Zangrando's detailed style would lend itself well to capturing the textures, light, and atmosphere of city streets, squares, or private courtyards. The mention of classical and Gothic elements in Bison further underscores an interest in architecture, possibly historical buildings that held significance within the regions he depicted. Through these works, Zangrando documented his surroundings, preserving views of Italy during a time of gradual modernization.

Personal Struggles and Artistic Expression

Beyond landscapes and cityscapes, Zangrando's art was also deeply intertwined with his personal experiences, particularly the psychological impact of war. Sources indicate that he suffered from depression stemming from war trauma. In a fascinating intersection of art and therapy, he reportedly turned to painting as a means of processing these difficult experiences. This endeavor was apparently guided by the psychiatrist Edoardo Weiss, a notable figure who was himself a student of Sigmund Freud and a pioneer of psychoanalysis in Italy. This connection highlights the potential therapeutic role of artistic creation and Zangrando's personal journey through psychological distress.

Furthermore, Zangrando also engaged with photography. His photographic work is described as capturing unique artistic scenes, including challenging subjects such as images related to the treatment of war wounds (the source mentions photographs documenting treatments involving gunpowder, likely referring to medical practices of the era for certain types of injuries). This use of photography suggests Zangrando was exploring different mediums of visual expression and was unafraid to confront difficult realities through his lens. It positions him as an artist sensitive to the traumas of his time and using his creative skills, in both painting and photography, to navigate and perhaps make sense of them.

Connections and Context in the Art World

While described as largely self-taught, Giovanni Zangrando was not entirely isolated from the art world. His name appears in records connected to Antonio Cenedese, associated with a family known for glassmaking in Murano, Venice. This suggests Zangrando had interactions within the local artistic and artisan communities of the Veneto region, even if specific collaborative projects are not documented. The art scene in Venice and its surroundings remained vibrant, encompassing not only painting but also decorative arts like glasswork.

There is no strong evidence linking Zangrando directly to major named art movements of the early 20th century, such as Futurism, which was exploding onto the Italian scene with artists like Umberto Boccioni and Carlo Carrà, or the Metaphysical painting of Giorgio de Chirico. His style appears more rooted in the representational traditions of the previous century. Compared to international developments, his detailed realism differs significantly from the light-obsessed works of French Impressionists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, or the socially charged Realism of Gustave Courbet. Zangrando represents a more conservative, though technically proficient, path.

He did achieve a degree of recognition, participating in exhibitions and finding success during his career. The mention of his work Passeggio Sant’Andrea in a 1984 Trieste exhibition catalog indicates that his paintings continued to be valued and studied decades after his death. He also reportedly participated in an event or group named "Antiguo Segundo," though details about this remain scarce. His career seems characteristic of many skilled regional artists who contribute significantly to their local art scene without necessarily achieving the international fame of avant-garde pioneers or artists working in major metropolitan centers like Paris or Milan, where figures like Amedeo Modigliani were forging distinct paths.

Legacy and Recognition

Giovanni Zangrando's legacy is primarily that of a dedicated Italian painter working within the traditions of oil painting, focusing on landscape, architecture, and potentially scenes of daily life. His work reflects the artistic environment of the Veneto region in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, demonstrating technical skill and a keen eye for detail. While not associated with revolutionary art movements, his commitment to representational painting provides a valuable counterpoint to the more radical experiments occurring elsewhere in Italy and Europe.

His personal story adds another layer of interest, particularly the connection between his art, war trauma, and early psychoanalytic thought through his contact with Edoardo Weiss. His use of photography alongside painting also marks him as an artist exploring multiple visual media. Although detailed information about his life and a comprehensive catalog of his works may be limited compared to more famous artists, his known paintings like Isola del Mare, Paesaggio della chiesa di Cadore, and Passeggio Sant’Andrea secure his place as a noteworthy figure in regional Italian art history.

Conclusion: A Painter of His Time and Place

Giovanni Zangrando (1867-1941) navigated the Italian art world during a period marked by both adherence to tradition and the stirrings of modernism. Rooted in the rich artistic soil of Treviso and the Veneto region, he developed a style characterized by skilled oil technique, detailed realism, and a focus on landscape and architectural subjects. His works capture specific locations and moments, reflecting the enduring appeal of representational painting.

While perhaps overshadowed by the giants of Italian art history or the leaders of avant-garde movements, Zangrando's career is significant. His engagement with personal trauma through art, guided by a pioneer of psychoanalysis, and his exploration of photography alongside painting reveal an artist grappling with the complexities of his inner life and the changing world around him. He remains a figure worthy of attention for his contribution to Italian painting and for the window his work offers onto the art and life of his specific time and place.