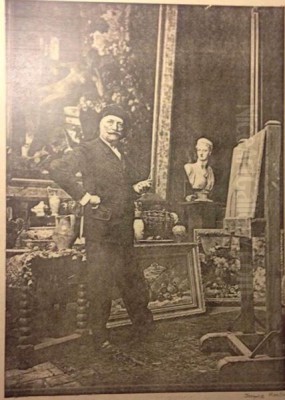

Jacques Martin, a notable French painter born in Villeurbanne near Lyon in 1844 and passing in 1919, carved a distinct niche for himself in the vibrant art world of late 19th and early 20th century France. Initially embarking on a career in chemical engineering after studies at the prestigious Ecole Centrale de Lyon, Martin's innate passion for art eventually led him down a different path. He became a largely self-taught artist, a testament to his dedication and natural talent, eventually gaining recognition for his exquisite flower still lifes, though his oeuvre also encompassed captivating landscapes, portraits, and genre scenes. His journey reflects a profound personal transformation, moving from the precise world of science to the expressive realm of painting, where he would make significant contributions, particularly within the Impressionist movement and the Lyonnaise School of painting.

From Engineering to Easel: An Unconventional Beginning

The mid-19th century was a period of immense industrial and scientific advancement, and it was in this environment that Jacques Martin first pursued a technical career. His training as a chemical engineer provided him with a structured, analytical mindset. However, the allure of the arts proved irresistible. Around the year 1878, Martin made the decisive shift to dedicate himself to painting. This was not a gradual transition facilitated by formal academic art training, which was the conventional route for aspiring artists of his time, often involving rigorous study at institutions like the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Instead, Martin cultivated his skills independently.

He established a studio within his own factory, a rather unconventional setting that perhaps underscores his practical origins and his determination to integrate his newfound passion into his life. This self-directed learning path allowed him to explore artistic techniques and theories on his own terms, free from the rigid constraints of academic tradition. It was this independent spirit that likely enabled him to readily embrace the revolutionary ideas of Impressionism that were challenging the established art world. His early efforts were encouraged by the Lyonnais painter François Vernay, who recognized Martin's burgeoning talent.

Embracing Impressionism: Light, Color, and Modernity

Jacques Martin's artistic development coincided with the flourishing of Impressionism, a movement that had radically altered the landscape of art in France. Artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, and Berthe Morisot were pioneering new ways of seeing and representing the world, emphasizing the fleeting effects of light and color, often painting en plein air (outdoors) to capture these transient moments. Martin was quick to absorb and adapt these avant-garde techniques.

His work became characterized by a bold use of color and a rich, vibrant palette. He demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of how colors interact, often mixing pure hues directly on the canvas or placing them side-by-side to create a luminous effect, a hallmark of Impressionist practice. His brushwork, too, likely adopted the broken, visible strokes typical of the movement, designed to convey the immediacy of sensory experience rather than a polished, academic finish. This approach was particularly effective in his celebrated flower still lifes, where he could explore the interplay of light on delicate petals and the lushness of varied textures. He was adept at blending pure colors with secondary or intermediate tones, achieving a remarkable harmony and vitality in his compositions.

The Lyonnaise School and National Recognition

While Paris was undoubtedly the epicenter of the French art world, Lyon also possessed a dynamic artistic community, often referred to as the Lyonnaise School. Jacques Martin became an important figure within this regional school, contributing to its reputation for embracing modern artistic currents, including Impressionism. The Lyonnaise School, while perhaps not as internationally renowned as its Parisian counterpart, fostered a supportive environment for artists and provided crucial platforms for exhibition.

Martin regularly exhibited his works at the Salon de Lyon, the premier art exhibition in his home city. His participation in these local Salons was vital for establishing his reputation and connecting with local patrons and fellow artists. Significantly, he also showcased his paintings at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris, beginning in 1881. The Salon des Indépendants was founded by artists like Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, and Albert Dubois-Pillet as an alternative to the official, jury-based Paris Salon, offering a space for more experimental and avant-garde art to be seen without the risk of rejection by conservative juries. Martin's presence in these Parisian exhibitions indicates his ambition and his alignment with the progressive art movements of his day. His talent did not go unnoticed by his peers; he garnered the admiration of prominent artists such as Auguste Renoir and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, figures of immense stature, whose appreciation speaks volumes about the quality and impact of Martin's work.

Mentorship and Artistic Circles

The guidance and encouragement of François Vernay (1821-1896) were pivotal in Jacques Martin's early artistic career. Vernay, himself an established painter from Lyon known for his still lifes and landscapes, provided Martin with valuable advice and, crucially, helped him navigate the exhibition landscape, facilitating his entry into both Parisian and Lyonnais Salons. This mentorship highlights the importance of artistic networks, even for a self-taught painter.

Martin's connections extended further. He was known to have taught painting, and one of his students was Jeanne Bardey. Bardey would later move to Paris and become a student and close associate of the monumental sculptor Auguste Rodin. While an indirect connection, it illustrates Martin's role as an educator and his place within the broader artistic currents that flowed between regional centers like Lyon and the capital. His association with the Lyonnaise School also placed him in the company of other notable Lyon-based artists of the era, such as Louis Carrand and Jean Seignemartin, who, like Martin, contributed to the region's artistic vibrancy and engagement with Impressionist ideas.

Master of Floral Still Lifes

While Jacques Martin's talents extended to landscapes, portraits, and genre scenes, he achieved particular renown for his flower still lifes. This genre, with its rich history dating back to Dutch Golden Age painters like Rachel Ruysch and Jan van Huysum, offered artists a contained yet infinitely variable subject through which to explore color, light, form, and texture. For an Impressionist, flowers provided the perfect motif to study the effects of light on vibrant, natural colors.

Martin's floral compositions were celebrated for their freshness, their dynamic arrangements, and the skillful rendering of different species of flowers. Works often titled generically, such as "Vase de Roses," "Bouquet de Fleurs," or "Chrysanthèmes dans un Vase," would have showcased his ability to capture the delicate translucency of petals, the subtle gradations of color, and the overall atmosphere of abundance and natural beauty. He would have paid close attention to the way light interacted with the surfaces, creating shimmering highlights and deep, velvety shadows, bringing an almost tactile quality to his paintings. His approach would have differed from the highly detailed, symbolic still lifes of earlier periods, instead focusing on the immediate visual impact and the emotional response evoked by the beauty of the blooms. Artists like Henri Fantin-Latour also excelled in flower painting during this period, though often with a more traditional, smoother finish than a dedicated Impressionist like Martin might employ.

Landscapes and Portraits: Expanding the Vision

Beyond his celebrated still lifes, Jacques Martin also applied his Impressionist sensibilities to landscapes. Painting "en plein air" was a cornerstone of Impressionism, and Martin likely ventured into the countryside around Lyon and perhaps further afield to capture the changing light and atmosphere of the natural world. His landscapes would have featured the characteristic broken brushwork and attention to atmospheric perspective seen in the works of masters like Alfred Sisley or Camille Pissarro, focusing on the overall impression of a scene rather than meticulous detail. Titles such as "Paysage animé" (Animated Landscape) or "Vue de la Rivière" (View of the River) suggest an interest in capturing not just static scenery but also the life and movement within it.

His portraiture, though perhaps less central to his fame, would have also benefited from his understanding of light and color. Impressionist portraiture, as seen in the works of Edgar Degas or Berthe Morisot, often sought to capture the personality and psychological presence of the sitter in a more informal and immediate way than traditional academic portraiture. Martin's portraits likely displayed a similar concern for capturing a sense of life and individuality, using his vibrant palette to model form and convey character.

Artistic Techniques and Style Revisited

Jacques Martin's style was firmly rooted in Impressionist principles. His commitment to capturing the visual sensations of a moment, particularly the effects of light and color, drove his technical choices. The "bold colors" and "rich palette" noted by observers point to his embrace of the brighter, more varied range of pigments that became available in the 19th century, and his willingness to use them in daring combinations.

His method of "mixing pure colors with secondary or intermediate tones" to create "harmony and vitality" is a key aspect of Impressionist color theory. Rather than pre-mixing all colors on the palette to achieve smooth gradations, Impressionists often juxtaposed strokes of different colors on the canvas, allowing the viewer's eye to blend them optically. This technique, known as optical mixing, contributed to the characteristic vibrancy and shimmer of Impressionist paintings. Martin's skill in this area suggests a sophisticated understanding of color relationships, akin to that of his more famous Parisian contemporaries. The description of his work being "advanced in Impressionist techniques" underscores his mastery and his position at the forefront of this style, at least within the Lyonnais context.

Legacy and Museum Collections

The enduring quality of Jacques Martin's work is evidenced by its inclusion in several prestigious museum collections. His paintings can be found in the Musée du Louvre in Paris, a testament to his national significance. The Musée de Brou in Bourg-en-Bresse also holds examples of his art. Unsurprisingly, given his strong connections to his home city, his works are prominently featured in Lyon's own institutions: the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon and the Musée d'Art Contemporain de Lyon (though the latter might be a slight misattribution for a 19th-century artist, perhaps referring to works that bridge into early modernism or are held in a broader regional collection).

His legacy primarily rests on his contribution to the dissemination and development of Impressionism outside of Paris, particularly his role as a leading figure in the Lyonnaise School. He demonstrated that significant artistic innovation could thrive in regional centers, and his success provided an inspiring example for other artists in Lyon. His dedication to capturing the beauty of the everyday, especially through his luminous flower paintings, continues to resonate with audiences. He stands as an important link in the chain of French painting, a talented artist who successfully navigated the transition from a scientific career to a celebrated artistic one, leaving behind a body of work that reflects the light and color of his era. His contemporaries, beyond the already mentioned Renoir and Puvis de Chavannes, would have included the broader Impressionist group and Post-Impressionist pioneers like Georges Seurat and Paul Cézanne, whose work would have been emerging during the later part of Martin's career, further transforming the artistic landscape.

Conclusion: An Enduring Impression

Jacques Martin's journey from chemical engineer to respected Impressionist painter is a compelling narrative of passion and dedication. As a self-taught artist, he not only mastered the prevailing avant-garde techniques of his time but also became a significant proponent of Impressionism within the influential Lyonnaise School. His flower still lifes, in particular, are celebrated for their vibrant color, skillful handling of light, and lively execution, capturing the ephemeral beauty of nature with a distinctly modern sensibility.

His regular participation in the Salons of Lyon and Paris, including the progressive Salon des Indépendants, and the admiration he garnered from luminaries like Renoir and Puvis de Chavannes, affirm his standing in the French art world. While perhaps not as globally recognized as some of his Parisian contemporaries like Monet or Degas, Jacques Martin's contribution to French art, and specifically to the artistic life of Lyon, is undeniable. His works, preserved in notable museum collections, continue to offer a window into the Impressionist vision, showcasing a mastery of color and light that remains captivating to this day. He represents the depth and breadth of the Impressionist movement, demonstrating its reach and adaptation beyond the confines of the capital, and stands as a testament to the enduring power of artistic expression.