Luis de Morales, often hailed as "El Divino" (The Divine), stands as a singular figure in the landscape of sixteenth-century Spanish art. Active primarily between the 1540s and his death in 1586, Morales carved a unique niche for himself, focusing almost exclusively on intensely devotional religious imagery. Working predominantly from the provincial city of Badajoz in the Extremadura region, far from the bustling artistic centers of Seville or the court in Madrid, he developed a highly personal and recognizable style that resonated deeply with the spiritual fervor of Counter-Reformation Spain. His paintings, typically small-scale panels intended for private contemplation, are characterized by their technical refinement, emotional intensity, and a distinctive blend of influences that set him apart from his contemporaries.

Origins and Artistic Formation

Pinpointing the exact birth year of Luis de Morales remains a challenge for art historians, with estimates generally placing it between 1510 and 1520. While his life unfolded primarily in Badajoz, where he settled by 1539 and maintained a workshop for decades, the specifics of his early training are shrouded in some obscurity. It is plausible that he initially encountered Flemish artistic currents through painters active in Badajoz itself, such as Hernando Sturmio, a painter of Flemish origin. The meticulous detail and sharp realism often found in Northern European art certainly find echoes in Morales's mature work.

A more significant, though still debated, formative influence likely came from Seville. Some scholars propose that Morales spent time in the workshop of Pedro de Campaña (born Pieter de Kempeneer), a highly respected Flemish painter who arrived in Seville around 1537. Campaña brought with him a sophisticated style that merged Flemish precision with Italianate grandeur, particularly influenced by Raphael and Michelangelo. If Morales did train with Campaña, even for a short period, it would have exposed him to the latest artistic trends and techniques circulating from both Italy and Northern Europe, providing a crucial foundation for his own stylistic synthesis. However, other historians argue that Morales was already active independently by the mid-1530s, suggesting his training might have occurred earlier, possibly within Castile.

Regardless of the precise locations and masters, it is clear that Morales absorbed various artistic currents prevalent in Spain during the High Renaissance and early Mannerist periods. Spain, at this time, was a crossroads of European culture. Artists like Alonso Berruguete and Pedro Machuca had returned from Italy, bringing direct knowledge of the revolutionary works of the Italian masters. Simultaneously, the historical ties and trade routes with the Low Countries ensured a continuous influx of Flemish art and artists, whose emphasis on detailed realism and poignant emotional expression profoundly impacted Spanish taste. Morales emerged within this complex artistic milieu.

The Confluence of Influences: Italy and the North

The art of Luis de Morales is a fascinating testament to the selective assimilation of diverse artistic traditions. His work reveals a deep awareness of the Italian Renaissance masters, particularly Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael Sanzio. From Leonardo, Morales seems to have adopted the technique of sfumato, the subtle blurring of outlines to create soft transitions between tones, which lends a delicate, almost ethereal quality to the flesh tones of his figures, especially noticeable in his depictions of the Christ Child and the Virgin Mary. The compositional harmony and idealized grace found in the works of Raphael also appear to have informed Morales's sense of balance and figural arrangement, albeit adapted to a more emotionally charged context.

Michelangelo's influence, particularly his powerful, sculptural rendering of the human form, might be discerned in the anatomical definition Morales sometimes employed, though Morales generally favored more slender and elongated figures than the Florentine master. Some scholars also point towards the influence of the Lombard school, followers of Leonardo in Milan, known for their gentle modeling and sweet expressions, which resonate with certain aspects of Morales's Madonnas.

Simultaneously, the impact of Northern European painting, particularly Flemish art, is undeniable and perhaps even more fundamental to his unique style. The meticulous attention to detail, the sharp focus, the rendering of textures like tears, hair, and fabric, and the profound, often sorrowful, emotional intensity connect Morales strongly to the tradition of artists like Rogier van der Weyden and Quentin Matsys. The pathos and direct emotional appeal characteristic of Flemish devotional painting found fertile ground in the religious climate of Spain, and Morales became a master at channeling this sensibility. The potential influence of German masters like Albrecht Dürer, whose prints circulated widely and were known for their linear precision and expressive power, cannot be discounted either.

Morales did not simply copy these sources; he forged them into a highly personal idiom. He synthesized the idealized beauty and technical innovations of Italy with the detailed realism and emotional depth of the North, creating a style perfectly suited to the demands of intense religious devotion in Counter-Reformation Spain.

The Signature Style of "El Divino"

Luis de Morales earned his sobriquet "El Divino" primarily because of the spiritual intensity and subject matter of his work, but also due to his distinctive and highly refined artistic style. His paintings are immediately recognizable. He favored oil paint on wooden panels, often of relatively small dimensions, suggesting they were primarily intended for private devotion in homes or small chapels rather than large public altarpieces. This intimate scale enhances the personal connection between the viewer and the sacred figures depicted.

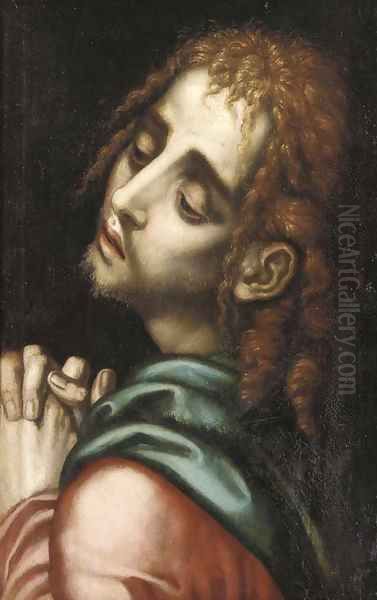

His compositions are typically simple and focused, often featuring half-length or bust-length figures set against dark, indeterminate backgrounds. This compositional strategy eliminates distracting narrative details and forces the viewer's attention onto the emotional and spiritual state of the subject. The use of strong chiaroscuro, with figures emerging dramatically from deep shadow, further heightens the sense of drama and isolates the subject in a space conducive to contemplation.

Morales's figures are often characterized by their slender proportions, elongated features, and smooth, pale flesh, rendered with exceptional delicacy using the sfumato technique derived from Leonardo. Yet, this idealized treatment is frequently combined with moments of startling realism, particularly in the depiction of suffering – the meticulously painted tears welling in the eyes of the Virgin or trickling down Christ's face, the sharp thorns of the crown, the rivulets of blood. This juxtaposition of idealized form and realistic detail creates a powerful emotional tension.

The emotional register of his work is predominantly one of pathos, piety, and sorrowful contemplation. His Virgins are tender yet often imbued with a sense of foreboding melancholy, while his depictions of Christ emphasize his suffering and sacrifice. The expressions are intense, internalized, inviting the viewer to empathize with the sacred drama unfolding. The color palette is often cool and restrained, dominated by subtle flesh tones, deep reds, blues, and the ubiquitous dark backgrounds, contributing to the overall somber and devotional mood. His technical execution was highly polished, with smooth surfaces and barely visible brushwork, reflecting the influence of Flemish finishing techniques.

Major Themes and Representative Works

Throughout his long career, Luis de Morales concentrated on a relatively limited range of religious subjects, revisiting them frequently with subtle variations for different patrons. His focus remained steadfastly on themes that encouraged personal piety and meditation on the central mysteries of the Christian faith.

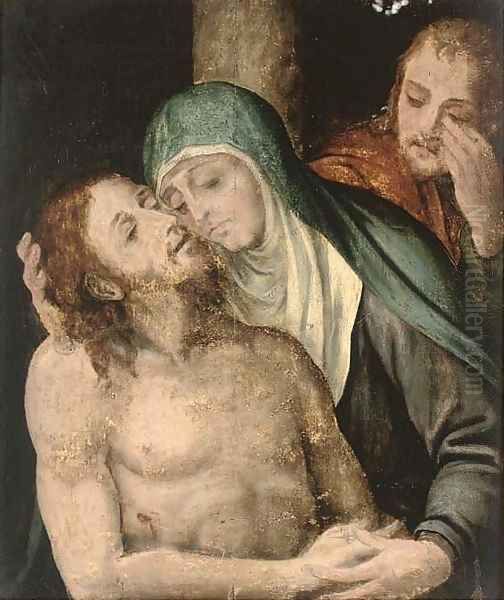

The Passion of Christ: Perhaps Morales's most famous and frequently repeated subjects revolve around the suffering of Christ. His numerous versions of Ecce Homo ("Behold the Man") depict Christ after his flagellation, crowned with thorns, often with ropes around his neck or hands bound. These images are stark and emotionally wrenching, focusing intently on Christ's physical and spiritual anguish. The realism in the depiction of wounds and tears is particularly striking. Similarly, his Pietà or Lamentation scenes, showing the grieving Virgin Mary holding the body of the dead Christ, are masterpieces of pathos. Morales conveys Mary's profound sorrow through her expression and posture, creating an image of intense maternal grief and devotion. Compared to the often more complex narrative scenes of the Passion by Italian artists like Titian, Morales isolates the emotional core of the moment.

Madonna and Child: Alongside the Passion, depictions of the Virgin and Child were central to Morales's output. These works often display a greater tenderness, emphasizing the maternal bond. Examples like the Virgen de la Leche (Virgin of the Milk), showing Mary nursing the infant Jesus, or variations where the Child holds a bird or a spindle (symbolic of the Passion to come), combine intimacy with theological depth. Even in these seemingly gentle scenes, a subtle melancholy often pervades the Virgin's expression, hinting at her awareness of her son's future sacrifice. His Madonnas possess a distinct character – elegant, sorrowful, and deeply spiritual, differing significantly from the sweeter, more worldly Madonnas of some Italian Renaissance painters like Raphael or Giovanni Bellini.

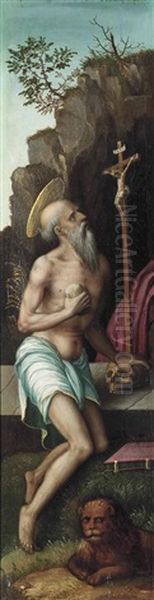

Other Sacred Figures: While less numerous than his depictions of Christ and the Virgin, Morales also painted other saints, often presented with the same intense focus and emotional depth. Images of penitent figures like Saint Jerome or ascetic figures like Saint John the Baptist allowed him to explore themes of devotion, contemplation, and spiritual discipline, applying his characteristic style to these subjects. Works like Pentecost, depicting the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles and the Virgin Mary, show his ability to handle multi-figure compositions while retaining his focus on individual spiritual experience.

His representative works, found today in major collections like the Museo del Prado in Madrid, the Museo de Bellas Artes in Bilbao, the National Gallery in London, and various churches in Spain and Portugal, consistently demonstrate his mastery of technique and his profound engagement with these core religious themes. Notable examples include The Virgin and Child (Prado Museum), Pietà (Bilbao Fine Arts Museum), Ecce Homo (Hispanic Society of America, New York), and the altarpiece panels from Arroyo de la Luz.

Context: The Counter-Reformation and Patronage

Luis de Morales worked during a period of intense religious transformation in Europe: the Counter-Reformation. The Catholic Church, responding to the challenges of the Protestant Reformation, sought to reaffirm its doctrines and revitalize spiritual life. Art played a crucial role in this effort, with the Council of Trent (concluded 1563) emphasizing that religious images should be clear, emotionally engaging, doctrinally correct, and serve to inspire piety and devotion among the faithful.

Morales's art perfectly aligned with these objectives. His focus on the suffering Christ and the sorrowful Virgin, rendered with poignant realism and emotional intensity, directly appealed to the viewer's empathy and encouraged contemplation of key Catholic tenets. His works served as powerful aids to private prayer and meditation, embodying the renewed emphasis on personal spiritual experience promoted by the Counter-Reformation.

His close relationship with Juan de Ribera, Bishop of Badajoz from 1562 to 1568 (later Archbishop of Valencia and a key figure in the Spanish Counter-Reformation), was significant. Ribera was a known patron of Morales, and his reformist zeal likely encouraged the painter's focus on deeply spiritual and didactic themes. This patronage provided Morales with important commissions and affirmed the value of his particular artistic vision within the church hierarchy.

There is also an anecdote connecting Morales to King Philip II of Spain. The story goes that the king, passing through Badajoz, met the aged and impoverished artist and granted him a pension. While perhaps embellished, it reflects Morales's reputation. Philip II was a major patron of the arts, famously commissioning works for the Escorial palace from artists like Titian and El Greco. Although Morales never became a court painter in the manner of these figures, the potential royal recognition underscores his standing as a significant artist of his time. His commissions came primarily from churches, monasteries, and private individuals within Extremadura and neighboring Portugal, fulfilling the devotional needs of his regional clientele.

Workshop, Influence, and Legacy

Like most successful artists of his era, Luis de Morales likely maintained an active workshop in Badajoz to help meet the demand for his popular compositions. Assistants would have aided in preparing panels, transferring designs, painting less critical areas, and producing replicas or variations of his most sought-after subjects, such as the Ecce Homo or Virgin and Child. This workshop practice explains the existence of numerous versions of certain themes, varying somewhat in quality and execution.

While his direct pupils are not extensively documented, one notable student associated with his circle is Juan Labrador. Interestingly, Labrador later specialized almost exclusively in still life painting, particularly depictions of flowers and fruit, becoming one of Spain's early masters in that genre. This suggests that while Morales's workshop focused on religious production, it could still foster talent that moved in different artistic directions.

Morales's influence extended beyond his immediate circle. His intense emotionalism and distinctive figural style, particularly the elongated forms and expressive faces, are seen by some art historians as anticipating aspects of the work of Domenikos Theotokopoulos, known as El Greco, who arrived in Spain in 1577. While El Greco developed a radically different and highly personal Mannerist style, the shared emphasis on spiritual intensity and expressive distortion provides a point of connection. Later Spanish Baroque painters, such as Francisco de Zurbarán, known for his stark realism and profound spirituality in depicting monastic life, also echo the deep devotional sentiment found in Morales's work, even if their styles differ significantly.

His reputation was not confined to Spain. His works were appreciated and collected in Portugal, where he also completed commissions. His fame endured after his death, and the early Spanish art historian Antonio Palomino included a biography of Morales in his influential compendium El Parnaso español pintoresco laureado (1724), cementing his place in the canon of Spanish masters and praising his divine subjects. Even centuries later, artists found inspiration in his work; the twentieth-century Surrealist Salvador Dalí, known for his own explorations of religious themes and meticulous technique, reportedly expressed admiration for Morales.

Anecdotes and Personal Life

Biographical details about Luis de Morales remain relatively scarce compared to some of his Italian contemporaries. He appears to have lived a life dedicated primarily to his art and his faith in Badajoz. Contrary to some earlier accounts suggesting he remained unmarried, historical records indicate he married Leonor de Chaves, who belonged to a prominent local family. This marriage likely provided him with valuable social connections and stability within the community. They had several children, including sons who may have assisted in his workshop.

One intriguing anecdote, mentioned in some sources, points to Morales's interest in subjects beyond traditional religious art. He is said to have had connections with mathematicians and astrologers, such as a certain Carlo Girolamo, and even incorporated an astrological chart relating to the Nativity into a painting of the Adoration of the Shepherds. While perhaps apocryphal or exaggerated, this story hints at a mind engaged with the broader intellectual currents of the Renaissance, where science, mathematics, and esoteric knowledge often intertwined. If true, it adds another layer to the personality of the artist known primarily for his intense piety.

The story of his encounter with Philip II, whether strictly factual or not, paints a picture of an artist who achieved considerable fame but perhaps not commensurate financial success, especially in his later years. It highlights the often precarious economic reality for artists, even those held in high esteem, working outside the main centers of courtly or ecclesiastical power. His enduring nickname, "El Divino," however, speaks volumes about how his contemporaries and subsequent generations perceived the profound spiritual quality that infused his art.

Critical Reception and Enduring Significance

Luis de Morales enjoyed considerable success and renown during his lifetime, particularly within Spain and Portugal. His works were sought after for their devotional power and technical skill. His nickname "El Divino" reflects this high contemporary esteem. Following his death, his reputation was maintained, notably through the writings of Palomino, who recognized his importance in the development of Spanish religious painting.

However, like many artists whose styles are closely tied to a specific historical moment and sensibility, Morales's fame experienced fluctuations over the centuries. During periods when tastes favored the grander Baroque or the lighter Rococo, his intense, somewhat austere, and deeply melancholic style may have seemed less appealing. The rise of Neoclassicism and later academic art also shifted focus away from the emotional directness that characterized his work.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, however, there was a renewed appreciation for Spanish art of the Golden Age and earlier periods. Scholars and collectors rediscovered the unique power and beauty of Morales's paintings. His technical mastery, his ability to convey profound emotion, and his significant role in reflecting the spiritual landscape of Counter-Reformation Spain were recognized anew. Today, he is firmly established as one of the most important and distinctive painters of the Spanish Renaissance. His works are studied for their unique synthesis of Italian and Flemish influences, their psychological depth, and their embodiment of a particular strand of intense Spanish piety.

Conclusion: The Master of Devotional Pathos

Luis de Morales, "El Divino," remains a compelling figure in the history of European art. Working from the relative isolation of Badajoz, he absorbed the major artistic currents of his time – the grace and technical innovations of the Italian Renaissance, the meticulous realism and emotional depth of Flemish painting – and forged them into a unique and powerful style. His unwavering focus on devotional subjects, particularly the suffering Christ and the sorrowful Virgin, resonated perfectly with the religious climate of Counter-Reformation Spain.

Through his simple, focused compositions, masterful use of light and shadow, delicate rendering of flesh, and unparalleled ability to convey profound pathos, Morales created intimate and intensely moving images designed for contemplation and prayer. While his range of subjects was narrow, his depth of feeling was immense. He stands as a master of devotional art, whose works continue to engage viewers with their technical brilliance and spiritual intensity. His legacy lies not only in his beautiful and haunting paintings but also in his demonstration of how provincial artists could absorb international influences and create a deeply personal and historically significant body of work, earning him a lasting place among the great masters of Spanish painting.