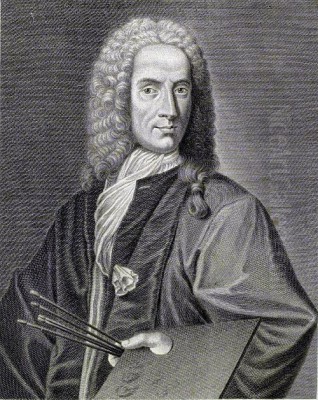

Antonio Zanchi (1631–1722) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of Italian Baroque painting, particularly within the rich artistic milieu of Venice during the Seicento. Born in Este, a town that had long been part of the Venetian Republic's territories, Zanchi's life and career would become inextricably linked with Venice, the city where he would hone his craft, achieve considerable fame, and leave an indelible mark through his powerful, often dramatically charged, canvases. His long life spanned a period of transition in Venetian art, and his work reflects both the enduring legacy of earlier masters and the evolving tastes of his time, particularly the penchant for dramatic intensity and emotional depth that characterized much of Baroque art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Venice

Antonio Zanchi's artistic journey began in his native Este, but like many aspiring artists of his era, he was drawn to Venice, the Serenissima, which remained a major artistic center despite its gradually waning political and economic power. In Venice, he immersed himself in a world steeped in artistic tradition, from the High Renaissance glories of Titian and Veronese to the dynamic energy of Tintoretto. His formal training involved apprenticeships with several painters. Early sources mention Giacomo Pedrali and Matteo Ponzone as his initial teachers.

Under Ponzone, it is noted that Zanchi was perhaps less directly influenced by the grand compositions of Tintoretto, suggesting an early inclination towards a different stylistic path. However, the most formative influence on the young Zanchi was undoubtedly Francesco Ruschi. Ruschi, himself a painter of considerable skill, played a crucial role in shaping Zanchi's artistic vocabulary. It was likely through Ruschi that Zanchi was more fully exposed to the burgeoning trends of Tenebrism and a heightened sense of realism, elements that would become hallmarks of his mature style. Ruschi's guidance helped Zanchi develop a keen sense for dramatic figural composition and the expressive potential of human anatomy and emotion.

The Embrace of Tenebrism and Key Influences

Zanchi's artistic development coincided with the widespread diffusion of Tenebrism, a style characterized by stark contrasts between light and shadow (chiaroscuro), often creating a sense of intense drama and focusing the viewer's attention on key elements of the composition. This style, pioneered by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio in Rome at the turn of the 17th century, had a profound impact across Italy and Europe. In Venice, Tenebrism found fertile ground, merging with the local tradition of rich color and dynamic composition.

Zanchi became a leading exponent of this "dark" style in Venice. His paintings often feature figures emerging from deep, shadowy backgrounds, illuminated by a strong, directional light source that sculpts their forms and heightens the emotional impact of the scene. This approach was particularly effective for the religious and mythological subjects he frequently depicted, allowing him to convey moments of intense spiritual revelation, suffering, or violence with visceral power.

Beyond Ruschi, Zanchi's style was also shaped by the work of other prominent artists. The Neapolitan painter Luca Giordano, known for his astonishing speed and versatility, and his dramatic, light-filled compositions, exerted an influence, particularly in Zanchi's handling of large-scale narrative scenes. Even more critical to the specific strain of Venetian Tenebrism that Zanchi practiced was the Genoese-born Giovanni Battista Langetti. Langetti, who was active in Venice from around 1650, was a master of depicting muscular, often tormented figures, frequently drawn from mythology or the Old Testament, rendered with a raw, almost brutal realism and dramatic chiaroscuro. Zanchi absorbed Langetti's intensity and focus on powerful anatomical representation, adapting it to his own narrative purposes. One might also see echoes of the earlier Spanish Tenebrist Jusepe de Ribera, whose work was influential in Naples and, through artists like Langetti, indirectly in Venice.

Mature Style: Drama, Realism, and Emotional Intensity

As Zanchi matured, his style solidified into a potent blend of dramatic composition, strong realism, and profound emotional depth. His figures are often characterized by their plasticity and a certain sculptural quality, their forms robust and their gestures emphatic. He paid close attention to anatomical detail, sometimes to the point of accentuating musculature or the signs of aging and suffering, lending a tangible reality to his subjects. The drapery in his paintings is often rendered with a characteristic sharpness, the folds deep and angular, contributing to the overall sense of dynamism and sometimes described as having an almost metallic quality.

A key feature of Zanchi's art is its theatricality. He was a master storyteller in paint, arranging his figures in complex, often crowded compositions that draw the viewer into the narrative. His use of light was not merely for modeling form but was a crucial expressive tool, highlighting faces, gestures, and key symbolic elements, while plunging other areas into shadow, thereby directing the viewer's emotional and intellectual response. This dramatic use of light and shadow was perfectly suited to the Counter-Reformation's emphasis on art that could move the faithful and inspire piety through vivid, emotionally engaging depictions of sacred stories.

His palette, while capable of richness, often leaned towards more somber tones, especially in his Tenebrist works, allowing the interplay of light and dark to take center stage. He showed a predilection for themes involving intense human experience – martyrdoms, miracles, scenes of plague and suffering, or dramatic mythological episodes. This focus on the "terribilità" or awesome power of his subjects resonated with the Baroque sensibility.

The Masterpiece: The Virgin Appears to the Plague Victims

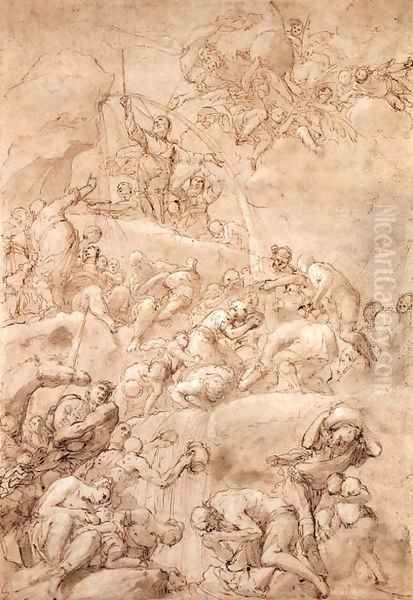

Among Zanchi's most celebrated and defining works is the monumental canvas, The Virgin Appears to the Plague Victims (also known as The Virgin Appears to the Plague-Stricken or The Plague of Florence). Painted around 1666, this powerful work is located on the main staircase of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Venice. This commission was particularly prestigious, as the Scuola Grande di San Rocco was one of Venice's most important lay confraternities, already famed for its magnificent cycle of paintings by Tintoretto.

Zanchi's painting depicts the horrors of a plague, likely referencing the devastating outbreak of 1630 that had ravaged Venice and other parts of Italy. The scene is one of profound suffering and desperation: bodies lie strewn across the foreground, figures writhe in agony, and survivors grieve or plead for divine intervention. Amidst this chaos, the Virgin Mary appears, accompanied by Saint Roch (the patron saint of plague sufferers and the titular saint of the Scuola), offering a beacon of hope and solace.

The painting is a tour-de-force of Zanchi's Tenebrist style. The dramatic chiaroscuro heightens the sense of tragedy and the miraculous nature of the apparition. The figures are rendered with a stark realism, their suffering palpable. Zanchi's skillful composition guides the viewer's eye through the complex scene, from the depths of human misery in the lower registers to the divine intervention above. The work is not only a testament to Zanchi's artistic prowess but also a poignant reflection of the anxieties and faith of his time. It stands as a quintessential example of Venetian Baroque art and is often cited as a cornerstone of the "tenebrosi" movement in the city. Its placement on the grand staircase ensured it would have a significant impact on all who entered the Scuola, serving as a powerful reminder of divine mercy in times of profound crisis.

Interestingly, Zanchi's work at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco was part of a larger decorative program. Another notable painting addressing the plague theme, Pietro Negri's The Madonna Saving Venice from the Plague of 1630, was also commissioned for the Scuola, and the two works offer a compelling comparison of how Venetian artists tackled such grave subjects.

Other Notable Commissions and Widespread Recognition

While The Virgin Appears to the Plague Victims is perhaps his most famous single work, Zanchi was a prolific artist who received numerous commissions throughout his long career. His reputation extended far beyond Venice, and he produced works for churches and private patrons in many other cities, including Padua, Treviso, Verona, Loreto, Bologna, Biella, Milan, and Bergamo. This geographical spread attests to his widespread recognition and the demand for his dramatic style.

In Venice itself, he executed important works for various churches. For instance, he created several large canvases depicting scenes from the life of the Virgin for the ceiling of the church of Santa Maria del Giglio (also known as Santa Maria Zobenigo). These works, filled with dynamic figures and celestial light, showcase his ability to handle complex, large-scale decorative schemes. He also contributed to the decoration of the Church of San Zaccaria and the Ospedaletto.

His subject matter was diverse, encompassing Old and New Testament scenes, lives of saints, and mythological narratives. Works like Abraham Teaching Astrology to the Egyptians, The Martyrdom of Saint Daniel of Padua, Moses Striking the Rock, and Alexander the Great and the Family of Darius demonstrate his versatility in handling different types of narrative and his consistent ability to imbue them with dramatic force. He was also a capable portraitist, though this genre formed a smaller part of his output.

Zanchi as an Educator and Theorist

Beyond his prolific output as a painter, Antonio Zanchi was also committed to the education of younger artists. He is recorded as having founded an academy in Venice, a common practice for established masters who wished to pass on their knowledge and maintain a workshop of assistants and pupils. While the specifics of his academy's curriculum are not fully known, it would undoubtedly have focused on drawing from life, studying the works of earlier masters, and mastering the principles of composition and perspective.

It is also mentioned that Zanchi wrote a manual intended for the instruction of young artists. Unfortunately, if such a manuscript was completed, it does not appear to have survived, or at least has not yet been widely identified. The existence of such a manual, however, points to Zanchi's intellectual engagement with his art and his desire to codify and transmit artistic principles, a characteristic shared by other artist-theorists of the Baroque period. His students would have included Francesco Trevisani, who later achieved fame in Rome, and Antonio Molinari, another significant Venetian painter whose style shows some affinities with Zanchi's dramatic approach.

Forays into Stage Design

The theatricality inherent in Zanchi's paintings found another outlet in the burgeoning world of Venetian opera. In the 17th century, Venice was a leading center for public opera, and the visual spectacle of these productions was a key element of their appeal. Zanchi is known to have contributed to this field, notably by providing the design for the frontispiece illustration for the libretto of the opera Artemisia, composed by Francesco Cavalli with a libretto by Nicolò Minato, which premiered in Venice in 1657 (though some sources state 1656 for the illustration). This involvement, even if limited, underscores his connection to the broader cultural life of Venice and his aptitude for visual storytelling across different media. The dramatic compositions and heightened emotional states in his paintings would have translated well to the demands of stage design.

The Artistic Milieu and Contemporaries

Antonio Zanchi operated within a dynamic and competitive artistic environment in Venice. While the towering figures of the High Renaissance like Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto cast long shadows, the 17th century saw the emergence of new talents and stylistic trends. Besides his teacher Ruschi and the influential Langetti and Giordano, Zanchi's contemporaries included a diverse group of painters.

Francesco Maffei, for example, was another prominent Venetian painter known for his eccentric, highly individual style, characterized by rapid brushwork and elongated figures. Sebastiano Mazzoni was another distinctive voice, whose work often featured complex allegories and a somewhat quirky elegance. Pietro Liberi was known for his more sensual and decorative mythological and allegorical scenes. Later in Zanchi's life, younger artists like Gregorio Lazzarini (who would become the teacher of Giambattista Tiepolo) and the aforementioned Antonio Molinari were active, carrying Venetian painting towards the Rococo splendors of the 18th century. Even painters working in different genres, like the celebrated pastel portraitist Rosalba Carriera, contributed to the richness of the Venetian art scene during Zanchi's lifetime. Zanchi's robust, Tenebrist style provided a distinct and powerful alternative to some of the more decorative or classicizing trends of the period.

The Enigma of the Inquisition

An intriguing and somewhat mysterious episode reported in some accounts of Zanchi's life is his alleged expulsion from Venice by the Holy Office of the Inquisition. The details surrounding this event, including its precise date and the specific reasons for such a drastic measure, remain obscure. If true, it would have been a significant disruption to his career and personal life.

Speculation regarding the cause could range from unorthodox religious views (perhaps an openness to Reformation ideas, which the Venetian Republic, while Catholic, sometimes tolerated to a greater degree than Rome for pragmatic reasons) to aspects of his art being deemed inappropriate or challenging to authority. The dramatic, sometimes violent, and intensely human portrayal of sacred figures in Tenebrist art could, in some contexts, be viewed with suspicion. However, without more concrete evidence, this remains a shadowy part of his biography. Given his extensive and successful career in Venice, if an expulsion did occur, it may have been temporary, or the matter resolved. The inclusion of this detail in his biography adds a layer of intrigue to his persona.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Antonio Zanchi enjoyed a remarkably long life and career, continuing to paint into his old age. He died in Venice in 1722, at the venerable age of 91. By the time of his death, artistic tastes were already beginning to shift towards the lighter, more airy and decorative style of the Rococo, which would find its supreme Venetian exponent in Giambattista Tiepolo. However, Zanchi's impact, particularly his mastery of dramatic narrative and the emotional power of Tenebrism, remained significant.

His numerous altarpieces and large-scale narrative paintings in churches and public buildings throughout Venice and Northern Italy ensured his visibility for generations. He was a key figure in maintaining Venice's reputation as a major center for painting during the 17th century, a period sometimes seen as a decline from its Renaissance peak, but which in reality was a time of complex artistic evolution and enduring creativity. Zanchi and his Tenebrist contemporaries provided a vital link in the chain of Venetian artistic tradition, adapting international Baroque trends to the local context.

His influence can be seen in the work of his pupils and followers, who continued to explore the possibilities of dramatic lighting and emotional expression. While the overt darkness of Tenebrism would eventually give way to brighter palettes, the emphasis on dynamic composition and psychological intensity that Zanchi championed remained an important undercurrent in Venetian art.

Conclusion: A Force in Venetian Seicento Painting

Antonio Zanchi was more than just a competent painter of his time; he was a formidable artistic force who significantly shaped the character of Venetian painting in the latter half of the 17th century. His embrace of Tenebrism, infused with a Venetian sensibility for color and drama, resulted in works of compelling power and emotional resonance. From the harrowing depiction of plague in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco to his numerous altarpieces and mythological scenes, Zanchi consistently demonstrated a masterful ability to translate complex narratives into vivid, engaging visual experiences.

His role as an educator, his contributions to stage design, and his prolific output across a wide geographical area testify to his energy and the high regard in which he was held. While perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his Renaissance predecessors or Rococo successors, Antonio Zanchi remains a crucial figure for understanding the evolution of Baroque art in Venice, a master of shadow and light whose canvases continue to speak with undiminished dramatic intensity. His legacy is that of an artist who deeply understood the human condition, portraying its trials, tragedies, and moments of divine hope with profound artistic skill and conviction.