Mateo Cerezo the Younger, a name that resonates with the vibrant yet often tragically brief careers of many great artists, stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of Spanish Baroque painting. Active during a period of immense artistic fervor and innovation in Spain, Cerezo, despite his short life, carved out a distinct niche for himself, particularly noted for his deeply emotive religious scenes and his skilled, if less voluminous, contributions to still life painting. His work reflects the dynamic artistic environment of 17th-century Madrid, a melting pot of native traditions and potent foreign influences, primarily from Italy and Flanders.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Burgos

Mateo Cerezo was born in Burgos, a historically significant city in northern Spain, around 1637. His artistic journey began under the tutelage of his father, Mateo Cerezo the Elder (c. 1600–1675), a painter of local repute. This familial apprenticeship was a common mode of artistic training in early modern Europe, providing young aspirants with foundational skills in drawing, paint preparation, and compositional principles from an early age. Growing up in his father's workshop, the young Mateo would have been immersed in the practicalities of the painter's craft, likely assisting with commissions and absorbing the prevailing artistic tastes of Castile.

Burgos, while not the artistic epicenter that Madrid or Seville were at the time, possessed its own artistic traditions and would have exposed Cerezo to various religious artworks in local churches and monasteries. It is documented that he demonstrated remarkable artistic talent from a young age, a precocity that undoubtedly encouraged his father and set the stage for his eventual move to a more stimulating artistic environment. The elder Cerezo's guidance would have provided a solid, if perhaps somewhat conservative, grounding in the techniques and iconographies prevalent in provincial Spanish art.

The Madrid Apprenticeship: Under Juan Carreño de Miranda

Recognizing the need for more advanced training and exposure to the cutting edge of Spanish art, Mateo Cerezo relocated to Madrid around 1654. This move was a pivotal moment in his career. In the capital, he entered the prestigious workshop of Juan Carreño de Miranda (1614–1685). Carreño was a leading figure of the Madrid school, a highly respected painter who would later succeed Diego Velázquez as court painter to King Charles II.

Apprenticeship under Carreño provided Cerezo with invaluable opportunities. He would have learned from a master deeply connected to the royal court and its collections, which housed masterpieces by Titian, Peter Paul Rubens, and Anthony van Dyck, among others. Carreño himself was known for his elegant portraits, dynamic religious compositions, and his skill in fresco painting, often collaborating with Francisco Rizi. In Carreño's studio, Cerezo would have honed his technique, refined his understanding of color and composition, and been exposed to the sophisticated tastes of the Madrid art scene. The influence of Carreño is discernible in Cerezo's developing style, particularly in the elegance of his figures and the richness of his palette.

Emergence of a Distinctive Style

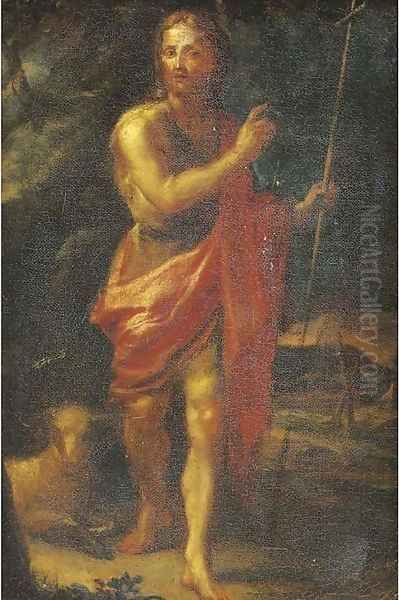

Following his apprenticeship, Mateo Cerezo began to forge his own artistic identity. While the imprint of his master, Carreño de Miranda, remained, Cerezo's work increasingly showcased his individual sensibilities. His style is characterized by a vibrant and often dramatic use of color, with a particular fondness for rich reds, blues, and yellows, often set against darker, atmospheric backgrounds—a technique that, while not strictly tenebrist in the manner of Caravaggio or early Jusepe de Ribera, certainly employed strong chiaroscuro for emotional impact.

His compositions became more complex and dynamic, reflecting the prevailing Baroque taste for movement and theatricality. Cerezo demonstrated a remarkable ability to convey intense emotion, particularly in his religious paintings, where figures are often depicted in moments of spiritual ecstasy, profound suffering, or tender devotion. There's a palpable sensitivity in his brushwork, which could be both fluid and precise, capturing the texture of fabrics, the softness of flesh, and the intensity of a gaze. His early works show a clear debt to the Venetian colorism of Titian and the elegant dynamism of Flemish Baroque painters like Van Dyck, influences likely absorbed through studying works in the royal collections and those accessible through his master.

Key Thematic Concerns: Religious Devotion

The vast majority of Mateo Cerezo's oeuvre is dedicated to religious themes, a reflection of the profound piety of Counter-Reformation Spain and the primary source of artistic patronage from the Church and devout individuals. He painted numerous scenes from the life of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and various saints, often imbuing them with a deeply personal and accessible emotional quality.

One of his most recurrent and powerful subjects was the Penitent Magdalene. His depictions of Mary Magdalene, such as the version often referred to as Madonna of Magdala (though more accurately Penitent Magdalene), are celebrated for their blend of sensuous beauty and spiritual contrition. These works typically show the saint in a landscape or cave, scantily clad, with attributes like a skull, a crucifix, and a book, her eyes often turned heavenward in tearful repentance. Cerezo’s handling of this theme showcases his skill in rendering human anatomy, luxurious textures (like her flowing hair), and conveying profound pathos. These paintings resonated deeply with Baroque sensibilities, which emphasized repentance and the emotional experience of faith.

Another significant religious work is his Ecce Homo (Behold the Man). In these depictions, Cerezo focuses on the suffering Christ, crowned with thorns and presented to the crowd. He masterfully conveys Christ's physical torment and divine resignation, often using dramatic lighting and a rich, almost visceral application of paint for the wounds and blood, yet always maintaining a sense of dignity. The influence of Titian's similar compositions, and perhaps even Van Dyck's pathos, can be felt in these powerful images.

His Saint Dominic in Prayer is another example of his capacity for depicting intense spiritual devotion. Such works were crucial for altarpieces and private devotional contexts, aiming to inspire piety in the viewer through empathetic engagement with the saint's experience. Cerezo also undertook larger commissions, including altarpieces for various churches and convents, such as the reported works for the Convent of San Isabel in Madrid. These larger-scale projects would have demanded sophisticated compositional skills and the ability to manage multiple figures within a coherent narrative.

Mastery of Still Life Painting

While religious paintings formed the core of his output, Mateo Cerezo also demonstrated considerable talent in still life painting, or bodegón, a genre that flourished in Spain during the 17th century. Spanish still lifes, pioneered by artists like Juan Sánchez Cotán with his austere, almost mystical arrangements, and later developed by figures such as Juan van der Hamen y León and Francisco de Zurbarán (in his religious still lifes), often carried symbolic weight or simply celebrated the beauty of everyday objects.

Cerezo's still lifes, such as the Kitchen Still Life (Bodegón de cocina) or Still Life with Fish, are characterized by their rich textures, careful observation, and skillful rendering of light and shadow. These works often feature humble kitchen items, game, or fish, arranged in a manner that is both naturalistic and artfully composed. His ability to capture the glistening scales of fish, the rough texture of earthenware, or the sheen of metal objects was remarkable. Though fewer in number compared to his religious works, his still lifes are considered important contributions to the genre and demonstrate his versatility as an artist. They often possess a warmth and richness that distinguishes them from the more severe compositions of some of his predecessors. Some scholars note a connection in style or subject matter to the still lifes of Antonio Pereda y Salgado, another prominent Madrid artist known for his vanitas and kitchen scenes.

Notable Commissions and Representative Works

Throughout his relatively brief career, Mateo Cerezo produced a body of work that, while not as extensive as some of his longer-lived contemporaries, contains several masterpieces that secure his place in Spanish art history.

The Penitent Magdalene (various versions, including one in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, and others in Spanish collections like the Museo del Prado, Madrid) remains one of his most iconic subjects. These paintings are lauded for their delicate balance of sensuality and spirituality, their rich coloring, and the expressive rendering of the saint's emotional state.

His Ecce Homo paintings, found in collections such as the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest and the Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, are powerful testaments to his ability to portray suffering with both realism and profound dignity. The dramatic lighting and the focus on Christ's face and torso create an intensely intimate and moving image.

The Assumption of the Virgin, a theme popular in Baroque art, was also tackled by Cerezo. Such compositions allowed for dynamic arrangements of figures, swirling drapery, and a sense of heavenly ascent, all hallmarks of the High Baroque style.

Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata is another subject he explored, depicting the mystical experience of the popular saint with characteristic emotional intensity. The dramatic interplay of light and shadow would have been key to conveying the divine nature of the event.

His Saint Nicholas of Tolentino with Souls in Purgatory (mentioned in some sources) would have been a complex theological subject, requiring Cerezo to depict both the saintly intercessor and the suffering souls, a theme that gained prominence during the Counter-Reformation.

The Nativity or Pledge of the Passion (Natividad o Prenda de la Pasión) suggests a more complex iconographic program, possibly blending the joy of Christ's birth with premonitions of his future suffering, a common theological juxtaposition in Christian art. Cerezo's skill in imbuing scenes with multiple layers of meaning would have been crucial here.

Many of his works were destined for churches in Madrid and his native Burgos, as well as for private collectors. The dispersal of his works over time means that they are now found in various prestigious museums across Spain and internationally, including the Museo del Prado, the Museo Lázaro Galdiano in Madrid, the Museum of Burgos, and collections abroad.

Influences and Artistic Dialogue

Mateo Cerezo's artistic development was shaped by a confluence of influences. His initial training with his father provided the groundwork. The subsequent period with Juan Carreño de Miranda in Madrid was transformative, exposing him to the sophisticated courtly style and the rich artistic resources of the capital.

The influence of Venetian Renaissance masters, particularly Titian, is evident in Cerezo's rich color palette and his sensuous rendering of flesh and fabric. Titian's works were highly prized in the Spanish royal collection, and their impact on generations of Spanish painters, including Velázquez and Carreño, was profound. Cerezo clearly absorbed these lessons in colorism and expressive brushwork.

Flemish Baroque painting, especially the work of Anthony van Dyck, also left its mark. Van Dyck's elegant portraiture and his emotionally charged religious scenes, characterized by fluid lines and refined compositions, find echoes in Cerezo's style. The international character of the Madrid art scene, facilitated by diplomatic ties and the royal family's artistic patronage, meant that Flemish art was well-represented and influential.

Within the Spanish context, besides his master Carreño, Cerezo's work shows affinities with that of Antonio Pereda y Salgado (1611–1678). Pereda was known for his rich still lifes, vanitas paintings, and religious scenes, often characterized by a similar warmth of color and detailed realism. It's plausible that Cerezo was familiar with Pereda's work, as they were contemporaries in Madrid.

The overarching influence of Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), the giant of the Spanish Golden Age, also permeated the Madrid school. While Cerezo's style is distinct from Velázquez's more restrained naturalism and profound psychological depth, the high standards of painterly technique and sophisticated composition set by Velázquez undoubtedly challenged and inspired younger artists in the capital.

Francisco Herrera "el Mozo" (the Younger, 1622–1685), another prominent contemporary in Madrid known for his dynamic and colorful style, particularly in large-scale religious works and still lifes with fish, represents another point of comparison. Both artists contributed to the vibrant, late Baroque aesthetic that characterized the Madrid school after Velázquez. Some sources also mention a Francisco Vergés, possibly referring to a lesser-known contemporary or perhaps Francisco de Burgos Mantilla, a still-life specialist whose work Cerezo might have known.

Contemporaries and the Madrid School

The Madrid school of the mid-to-late 17th century was a dynamic environment. After the death of Velázquez in 1660, artists like Juan Carreño de Miranda and Francisco Rizi (1614–1685) became the dominant figures, particularly in royal and ecclesiastical commissions. Cerezo was part of this generation, contributing to the evolution of the Baroque style in the capital.

Carreño and Rizi often collaborated on large decorative schemes, including frescoes in churches and palaces, developing a style that was grand, colorful, and highly theatrical. While Cerezo is not primarily known for fresco work, the prevailing aesthetic of this "High Baroque" Madrid style—characterized by energetic compositions, rich colors, and emotive figures—is clearly reflected in his easel paintings.

Other notable painters active in Madrid during or around Cerezo's time included Claudio Coello (1642–1693), who would become a leading figure in the later part of the century, known for his monumental altarpieces like the Sagrada Forma in El Escorial. While Coello was slightly younger, their careers would have overlapped, and they shared the common influences of the Madrid school. José Antolínez (1635-1675) was another exact contemporary known for his rich color and depictions of the Immaculate Conception.

The artistic scene was competitive but also collaborative, with artists often influencing one another and responding to similar sources of patronage. The Church remained a primary patron, commissioning altarpieces, devotional paintings, and large narrative cycles. Private patrons also sought religious works for their homes and chapels, as well as portraits and still lifes.

Personal Life and Social Context

Details about Mateo Cerezo's personal life are somewhat scarce, as is common for many artists of this period unless they achieved exceptional fame or were involved in extensive documented litigation or contracts. However, some archival information has shed light on certain aspects.

It is recorded that Mateo Cerezo married Maria Fernanda Campuzano in Madrid in 1664. She was reportedly four years his junior and had been previously married to a Joseph Giménez, who had passed away. An interesting detail from their marriage contract, as noted by some researchers, is that Cerezo did not provide any significant property or dowry, which might suggest that, despite his talent and growing reputation, he was not in a particularly strong financial position at the time. Such contracts often provide glimpses into the socio-economic realities of artists. The mention of an "unusual" female confessional statement within the marriage contract hints at the complex social and religious customs of the era, though further details on this specific aspect are often specialized.

His connections to the Madrid court, primarily through his master Juan Carreño de Miranda, would have been crucial for his career. Access to courtly circles and the potential for royal or aristocratic patronage were highly sought after by artists. While Cerezo may not have achieved the status of a court painter himself due to his early death, his association with Carreño placed him within this influential sphere.

A Premature End: Untimely Death and Legacy

Mateo Cerezo's promising career was tragically cut short. He died in Madrid in 1666, at the young age of approximately 29. The cause of his early death is not definitively known, a common occurrence in historical records of this period. Such premature deaths were not uncommon, robbing the art world of talents that were still maturing.

Despite his short lifespan, Cerezo left a significant mark on Spanish Baroque art. His ability to synthesize various influences—the color of Titian, the elegance of Van Dyck, the dynamism of Carreño, and the emotional intensity characteristic of Spanish piety—into a personal and compelling style was remarkable. Had he lived longer, he might well have risen to become one of the leading figures of the late Spanish Baroque, alongside artists like Claudio Coello.

His works continued to be appreciated after his death. His paintings were sought after by collectors and served as models for later artists. The emotional directness and vibrant palette of his religious scenes, in particular, ensured their enduring appeal in a culture that valued devotional art.

Historical Assessment and Enduring Influence

Art historians today recognize Mateo Cerezo the Younger as a gifted and important painter of the Madrid school during the Spanish Golden Age. While perhaps overshadowed in popular consciousness by giants like Velázquez, Zurbarán, or Murillo, Cerezo holds a respected place among the second generation of Baroque masters who flourished in the capital.

His paintings are valued for their technical skill, their rich and harmonious coloring, and their profound emotional resonance. He excelled in conveying the drama and pathos of religious narratives, making them accessible and moving for the 17th-century viewer. His contributions to still life, though less numerous, are also acknowledged for their quality and their place within the strong Spanish bodegón tradition.

The study of Cerezo's work provides valuable insights into the artistic currents of mid-17th-century Madrid, a period of transition and continued artistic excellence. His ability to absorb and personalize diverse influences demonstrates the cosmopolitan nature of the Madrid art world, which, despite Spain's political and economic challenges, remained a vibrant center of creativity.

His legacy endures in the numerous paintings preserved in museums and collections worldwide, allowing contemporary audiences to appreciate the talent of this brilliant, albeit short-lived, star of the Spanish Baroque. Mateo Cerezo's art serves as a poignant reminder of a prodigious talent extinguished too soon, yet one whose light continues to shine through his captivating canvases. His work stands as a testament to the enduring power and beauty of the Spanish Baroque, an era of profound faith and extraordinary artistic expression.