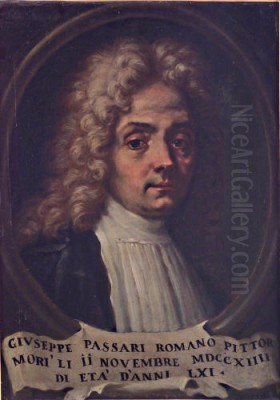

Giuseppe Passeri (1654–1714) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of late Baroque art in Rome. A painter and architect, he navigated the rich artistic currents of his time, absorbing the influences of his predecessors and contemporaries while forging a distinct, albeit often Marattesque, style. His career, predominantly based in Rome, was marked by prestigious commissions for ecclesiastical and private patrons, and his legacy is further cemented by his contributions as an art historian. This exploration delves into the life, artistic development, major works, and lasting impact of Giuseppe Passeri, placing him within the vibrant artistic milieu of 17th and early 18th-century Italy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Rome in 1654, Giuseppe Passeri was immersed in an artistic environment from a young age. His uncle, Giovanni Battista Passeri (c. 1610–1679), was not only a painter but also a respected biographer of artists, whose writings provide invaluable insights into the Roman art scene of the mid-17th century. It was under his uncle's initial guidance that Giuseppe likely received his foundational training in drawing and painting. This early exposure to both the practice and the history of art would have provided a solid grounding for the young artist.

However, the most decisive influence on Giuseppe Passeri's artistic trajectory came from his apprenticeship with Carlo Maratti (1625–1713). Maratti, or Maratta as he is often known, was the undisputed leading painter in Rome during the latter half of the 17th century and the early 18th century. His studio was a magnet for aspiring artists, and Passeri became one of his most devoted and successful pupils. Maratti's own style represented a classical and composed strand of Baroque, a reaction against the more exuberant and theatrical High Baroque of artists like Pietro da Cortona and Gian Lorenzo Bernini, favoring instead a grand manner rooted in the High Renaissance ideals of Raphael and the Bolognese classicism of Annibale Carracci.

Under Maratti, Passeri would have undergone rigorous training. This involved copying the works of his master and earlier masters, studying from life, and mastering the principles of composition, anatomy, and perspective. Maratti's emphasis on disegno (drawing and design) as the foundation of painting, combined with a refined sense of colore (color), deeply imprinted itself on Passeri. He learned to emulate Maratti's elegant figures, balanced compositions, and harmonious color palettes, becoming a proficient exponent of his master's style. The influence of artists revered by Maratti, such as Annibale Carracci, Guido Reni, and Nicolas Poussin, would also have been filtered through this tutelage, shaping Passeri's appreciation for classical clarity and idealized forms.

The Enduring Influence of Carlo Maratti

Carlo Maratti's dominance in the Roman art world cannot be overstated, and his influence on Giuseppe Passeri was profound and lifelong. Maratti's art was characterized by its grace, dignity, and technical polish. He championed a return to the classical ideals of the High Renaissance, particularly the art of Raphael, while infusing it with a Baroque sensibility for emotional expression and dynamic, yet controlled, compositions. This approach, often termed "Baroque Classicism," offered an alternative to the more dramatic and illusionistic styles of some of his contemporaries.

Passeri absorbed Maratti's methodology, including his meticulous preparatory process, which involved numerous drawings to refine poses and compositions. A specific technical trait Passeri adopted from Maratti was the extensive use of a red chalk or red wash underdrawing, often visible in his finished paintings and particularly evident in his preparatory sketches. This technique helped to establish the tonal values and structure of the composition before the application of color.

While Passeri was a faithful follower, he was not merely a slavish imitator. He developed his own subtle variations within the Marattesque idiom. Some scholars note a slightly softer modeling in Passeri's figures or a particular warmth in his color harmonies that distinguishes his work. Nevertheless, the stamp of Maratti's classicizing Baroque remained the bedrock of his artistic identity, ensuring his appeal to patrons who favored a more restrained and elegant form of religious and mythological painting. This connection to Maratti also provided Passeri with access to important circles of patronage and prestigious commissions.

Passeri's Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Baroque Dynamism and Classical Grace

Giuseppe Passeri's artistic style is best understood as a skillful fusion of the prevailing Baroque taste for dynamism and emotional intensity with an underlying classical structure and grace, largely inherited from Maratti. His figures, while often imbued with a sense of movement and expressive gesture, retain an idealized beauty and anatomical correctness rooted in classical principles. He avoided the extreme contortions or overwhelming theatricality found in some High Baroque works, opting instead for a more measured and harmonious presentation.

Color was a key element in Passeri's art. He employed a rich and varied palette, often favoring warm tones and subtle gradations to achieve a sense of volume and depth. His handling of drapery was typically fluid and elegant, revealing the forms beneath while adding to the compositional rhythm. Like Maratti, Passeri was adept at creating compositions that were both complex and clear, guiding the viewer's eye through the narrative with well-placed figures and a balanced distribution of light and shadow.

His mastery of chiaroscuro, the dramatic interplay of light and dark, was essential to his style. While not as stark or tenebrous as the earlier Caravaggisti, Passeri used light to model forms, create atmosphere, and highlight the emotional or narrative focus of his scenes. This skillful manipulation of light contributed to the overall sense of vitality and presence in his paintings. His works often exhibit a refined sensibility, appealing to the sophisticated tastes of Roman patrons who appreciated both technical virtuosity and intellectual content. The influence of Bolognese masters like Domenichino, another proponent of classical ideals, can also be discerned in the clarity and emotional restraint of some of his compositions.

Major Commissions and Religious Works

The bulk of Giuseppe Passeri's oeuvre consists of religious paintings, including large-scale altarpieces and frescoes for churches in Rome and surrounding areas. The Counter-Reformation's emphasis on art as a tool for religious instruction and inspiration continued to fuel demand for such works, and Passeri, with his Marattesque credentials, was well-positioned to receive significant commissions.

He contributed to the decoration of several important Roman churches. Among these were altarpieces for St. Peter's Basilica (though his most cited work there, St. Peter Baptizing the Centurion, is in the baptistery chapel of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, which was adapted from the Baths of Diocletian, or sometimes attributed to the Basilica itself in broader terms of Vatican commissions), Santa Maria in Vallicella (also known as Chiesa Nuova, a major center of the Oratorian movement), San Francesco a Ripa, Santa Caterina da Siena a Magnanapoli, and Santa Croce in Gerusalemme. These commissions placed him in the company of other leading artists of the day and solidified his reputation.

His work for the Duomo (Cathedral) of Viterbo, which included ceiling frescoes, was a significant undertaking outside Rome. Unfortunately, these frescoes, depicting scenes from the life of Saint Lawrence, were destroyed during World War II, a loss to our understanding of his capabilities in large-scale decorative schemes. The surviving preparatory drawings and contemporary accounts, however, attest to their quality and importance. These projects required not only artistic skill but also the ability to manage large compositions and, in the case of frescoes, to work quickly and confidently on a monumental scale. His religious works typically convey a sense of piety and devotion, rendered with the characteristic elegance and clarity of his style.

Key Masterpieces: Expressions of Faith and Artistry

Among Giuseppe Passeri's most celebrated works, two stand out for their representative quality and artistic merit: Saint Peter Baptizing the Centurion Cornelius and The Holy Family.

Saint Peter Baptizing the Centurion Cornelius, often cited as being in the Vatican or associated with St. Peter's Basilica, is a powerful depiction of a pivotal moment from the Acts of the Apostles. The composition is dynamic yet ordered, with Saint Peter as the central figure, his gesture of baptism both authoritative and benevolent. The Roman centurion Cornelius and his household are shown with expressions of awe and reverence. Passeri masterfully handles the grouping of figures, the rendering of varied textures (from armor to flowing robes), and the use of light to emphasize the spiritual significance of the event. The work exemplifies the grand manner of painting, suitable for its sacred context, and showcases Passeri's ability to convey complex narratives with clarity and emotional impact, echoing the compositional strategies of masters like Raphael and Annibale Carracci.

The Holy Family, a more intimate subject, reveals another facet of Passeri's artistry. One notable version is housed in the Crocefisso Monastery in Fara in Sabina. Such paintings, intended for private devotion or smaller chapels, allowed for a focus on tender human emotion within a sacred context. Passeri typically portrays the Virgin Mary, Saint Joseph, and the Christ Child with a gentle grace and serene dignity. The interplay of gazes and gestures creates a sense of familial love and divine harmony. The colors are often warm and inviting, and the lighting soft, enhancing the devotional atmosphere. This work, and others like it, demonstrates Passeri's versatility in adapting his style to different scales and purposes, always maintaining a high level of technical refinement and expressive sensitivity. These works reflect the enduring appeal of the Holy Family theme, popularized by artists like Federico Barocci and later refined by the Carracci school.

Draughtsmanship: The Foundation of Passeri's Art

Giuseppe Passeri was a prolific and highly skilled draughtsman. Drawing, or disegno, was considered the intellectual and practical foundation of art in the Italian tradition, and Passeri's numerous surviving drawings attest to his mastery of this discipline. His drawings served various purposes: quick compositional sketches to explore initial ideas, detailed studies of individual figures or drapery, and more finished presentation drawings, known as modelli, for patrons.

A significant collection of his drawings, numbering over 1,100 sheets and representing perhaps two-thirds of his known graphic oeuvre, is preserved in the Museum Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf, Germany. This collection provides an invaluable resource for understanding his working methods and artistic development. His drawings are typically characterized by fluid lines, confident handling of anatomy, and a skillful use of chalk (often red or black, sometimes combined with white heightening on colored paper) and pen and ink with wash.

These preparatory studies reveal the meticulous care with which he approached his painted compositions. He would often explore multiple solutions for a figure's pose or the arrangement of a group before settling on the final design. His drawings, like those of his master Carlo Maratti, are not merely functional but possess an intrinsic aesthetic quality, admired for their spontaneity and technical brilliance. They connect him to a long line of Italian masters, from Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo to the Carracci and Guido Reni, who placed a high premium on draughtsmanship. The study of his drawings reveals an artist constantly refining his vision, working through problems of form and expression on paper before committing them to canvas or fresco.

Passeri as an Architect

While primarily known as a painter, Giuseppe Passeri was also active as an architect. In the Baroque period, it was not uncommon for artists to be proficient in multiple disciplines; figures like Gian Lorenzo Bernini excelled as sculptors, architects, and even painters and playwrights. Passeri's architectural activities are less well-documented and perhaps less extensive than his painting career, but they form an integral part of his artistic identity.

His training would have included the study of architectural principles, as perspective and the convincing depiction of architectural settings were essential for painters, especially those undertaking large-scale fresco decorations that often incorporated illusionistic architecture (quadratura). His involvement in architectural projects likely grew out of his work as a painter decorating interior spaces.

Specific architectural commissions attributed to Passeri are not as widely known as his paintings. However, his understanding of architectural design is evident in the settings he created within his pictorial compositions. He demonstrated a capacity for designing structures that were both classically proportioned and dynamically Baroque. This dual role as painter-architect allowed him to conceive of decorative schemes in a holistic manner, where painted elements and architectural frameworks were harmoniously integrated. His architectural endeavors, though perhaps secondary to his painting, underscore the breadth of his artistic talents and his engagement with the multifaceted creative environment of Baroque Rome, where artists like Francesco Borromini and Carlo Rainaldi were shaping the city's architectural fabric.

The Vite: Passeri as Historian and Biographer

Beyond his achievements as a painter and architect, Giuseppe Passeri made a lasting contribution to art history through his writings. He compiled a collection of biographies of artists, titled Vite de' Pittori, Scultori, ed Architetti che hanno lavorato in Roma, morti dal 1641 fino al 1673. This work followed in the tradition of earlier artist-biographers like Giorgio Vasari and his own uncle, Giovanni Battista Passeri.

Giuseppe Passeri's Vite was prepared for publication but only appeared posthumously in 1772, edited by Giovanni Ludovico Bianconi. The book covers artists who were active in Rome and died between 1641 and 1673, a period of intense artistic activity that saw the flourishing of the High Baroque. His accounts provide valuable information about the lives, works, and artistic personalities of figures such as Alessandro Algardi, Francesco Mochi, François Duquesnoy, Pietro da Cortona, Andrea Sacchi, and Salvator Rosa, among others.

As an artist himself, Passeri brought an insider's perspective to his biographical sketches. He often included anecdotes, critical assessments, and details about artistic practice that might have been overlooked by a lay historian. While, like all such historical sources, it needs to be read critically and cross-referenced with other documents, Passeri's Vite remains an indispensable primary source for scholars of 17th-century Roman art. It offers a window into the artistic debates, rivalries, and collaborations of the era, and reflects the contemporary understanding and appreciation of the artists he profiled. His decision to undertake this scholarly work demonstrates a deep engagement with the history and theory of art, complementing his practical achievements as a creator.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu in Rome

Giuseppe Passeri worked during a vibrant and competitive period in Roman art. The city was the undisputed center of the art world, attracting artists from all over Italy and Europe. Papal patronage, along with commissions from noble families and religious orders, fueled a constant demand for new art and architecture.

Passeri's primary artistic relationship was, of course, with his master, Carlo Maratti. Maratti's studio was a hub, and Passeri would have interacted with other pupils and assistants, such as Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari and Agostino Masucci, who also became successful painters in the Marattesque tradition. Beyond Maratti's immediate circle, Rome was teeming with talent. Figures like Giovanni Battista Gaulli, known as Baciccio, were renowned for their breathtaking illusionistic ceiling frescoes, such as the vault of the Gesù, offering a more dynamic and overtly theatrical Baroque style than Maratti's.

Other notable painters active in Rome during Passeri's lifetime or slightly preceding it, whose work contributed to the artistic climate, included Ciro Ferri (a principal pupil and follower of Pietro da Cortona), Luca Giordano (the prolific Neapolitan painter who also worked in Rome), and the French classicists Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, whose influence, particularly Poussin's, was deeply felt in the classicizing tendencies of artists like Maratti and Sacchi. The legacy of Caravaggio, though from an earlier generation, continued to resonate in the dramatic use of light and naturalism found in the works of some artists.

Passeri also had direct collaborations and interactions. For instance, records mention his association with Padre Sebastiano Resta, a renowned collector and connoisseur of drawings, indicating Passeri's integration into the scholarly and artistic networks of the city. He was a member of the Accademia di San Luca, Rome's prestigious academy of artists, which played a crucial role in artistic education and the regulation of the profession. His student, Giuseppe Ghezzi, also became a notable painter and was part of the same artistic lineage. This rich environment of masters, rivals, collaborators, and patrons shaped Passeri's career and the reception of his work.

Later Career, Legacy, and Posthumous Reputation

In his later career, Giuseppe Passeri continued to be a productive artist, fulfilling commissions and maintaining his reputation as a leading exponent of the Marattesque style. He remained active until his death in Rome in 1714. His influence extended through his students, most notably Giuseppe Ghezzi, who succeeded him in certain roles and continued to propagate a similar artistic vision.

Passeri's legacy is that of a highly competent and refined painter who successfully navigated the dominant artistic currents of his time. While he may not have been a radical innovator on the scale of a Caravaggio or a Bernini, he was a master of his craft, producing works of considerable beauty and technical skill. His adherence to the classical principles championed by Maratti ensured that his art possessed an enduring quality of elegance and order, which appealed to the prevailing tastes of the late Baroque and early Rococo periods.

After his death, Passeri's reputation, like that of many Baroque artists, experienced fluctuations. The rise of Neoclassicism in the later 18th century led to a general decline in the appreciation for Baroque art, which was often criticized for its perceived extravagance or lack of "noble simplicity." However, the 20th and 21st centuries have seen a renewed scholarly interest in the Baroque period, and artists like Passeri are now studied and appreciated for their contributions within their historical context.

His works are found in numerous churches in Rome, and his drawings are preserved in major museum collections, most notably the aforementioned holdings in Düsseldorf. His paintings occasionally appear on the art market, with auction records reflecting a steady, if not spectacular, appreciation for his work. For instance, a painting depicting Saint Philip Neri was sold at Christie's, indicating continued collector interest. His Vite ensures his place not only as an artist but also as a valuable chronicler of his artistic era.

Conclusion: A Refined Voice in Roman Baroque Painting

Giuseppe Passeri emerges from the annals of art history as a distinguished painter and a significant figure in the Roman art scene of the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Deeply influenced by his master, Carlo Maratti, he became a prominent exponent of the classical Baroque style, characterized by its elegance, clarity, and technical refinement. His prolific output, primarily consisting of religious commissions for Roman churches, demonstrates his mastery of composition, color, and draughtsmanship. Works like Saint Peter Baptizing the Centurion Cornelius and his various depictions of The Holy Family showcase his ability to convey both grand narratives and intimate devotional scenes with skill and sensitivity.

Beyond his painted oeuvre, Passeri's extensive body of drawings reveals the meticulous preparatory process and intellectual rigor that underpinned his art. His contributions as an architect, though less prominent, further highlight his versatility. Perhaps one of his most enduring legacies is his Vite de' Pittori, Scultori, ed Architetti, which provides an invaluable contemporary perspective on the artists who shaped the Roman Baroque.

While he operated largely within the stylistic framework established by Maratti, Giuseppe Passeri was more than a mere follower. He infused his work with a personal sensibility, contributing to the rich tapestry of Roman art during a period of extraordinary creativity. His dedication to the principles of disegno and his ability to synthesize Baroque dynamism with classical grace ensure his place as a respected master, whose works continue to be admired for their beauty, skill, and devout expression. He remains a testament to the enduring power of the Roman artistic tradition and a key figure for understanding the transition from the High Baroque to the later, more refined phases of the era.