Pieter van Lint (1609-1690) stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the rich tapestry of 17th-century Flemish Baroque art. A versatile artist, he excelled as a painter of historical and religious subjects, genre scenes, and portraits, and also contributed designs for tapestries. His career, forged in the bustling artistic hub of Antwerp and refined during a formative period in Rome, reveals an artist adept at synthesizing the robust dynamism of his native tradition with the classical ideals encountered in Italy. Van Lint's extensive oeuvre, characterized by its clarity, refined execution, and narrative depth, found appreciation not only in the Low Countries but also across Europe and even in the Spanish colonies, marking him as an artist of international reach.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

Born in Antwerp in 1609, Pieter van Lint emerged during a golden age for the city's artistic production, albeit one increasingly dominated by the towering figure of Peter Paul Rubens. Van Lint's formal training commenced under Artus Wolffort (1581-1641), a painter whose own style was indebted to an earlier generation, particularly Otto van Veen, who had been Rubens's teacher. Wolffort's workshop provided a solid grounding in the fundamentals of painting. During this period, it was common practice for aspiring artists to hone their skills by copying the works of established masters. Van Lint diligently followed this path, reportedly frequenting Antwerp's churches to study and replicate compositions by leading contemporaries like Rubens, as well as earlier influential figures such as Maerten de Vos and members of the prolific Francken family, likely including Frans Francken the Younger. This practice not only developed his technical facility but also exposed him to a variety of stylistic approaches and iconographic traditions.

In 1633, a pivotal year in his early career, Pieter van Lint was officially recognized as a master by the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke. Membership in this prestigious institution was a prerequisite for practicing independently as an artist in the city, allowing him to take on apprentices and accept commissions in his own right. His early works from this Antwerp period likely reflected the prevailing tastes, demonstrating a solid understanding of composition, anatomy, and the dramatic use of light and shadow characteristic of the Flemish Baroque. However, like many ambitious Northern European artists of his time, Van Lint recognized the profound importance of experiencing Italian art firsthand.

The Pivotal Italian Sojourn: Rome (1633-1640)

Shortly after becoming a master, around 1633 or perhaps slightly later, Van Lint embarked on the customary journey to Italy, a veritable rite of passage for artists seeking to immerse themselves in the masterpieces of antiquity and the Renaissance, as well as the vibrant contemporary art scene. He settled in Rome, which at that time was the undisputed center of the European art world, pulsating with the creative energies of artists like Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Francesco Borromini, and Pietro da Cortona, who were shaping the High Baroque. The classical ideals, revived and reinterpreted by artists such as Annibale Carracci and his followers like Domenichino, also held considerable sway, alongside the lingering, powerful influence of Caravaggio's naturalism and dramatic chiaroscuro.

During his Roman sojourn, which lasted until approximately 1640, Van Lint was highly productive. He secured a significant commission from Cardinal Domenico Ginnasi, the Bishop of Ostia. For the Ginnasi family chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo (though some sources indicate the commission was for the family's private chapel or another church under Ginnasi's patronage), he executed a series of frescoes depicting the "Legend of the True Cross." This project, involving large-scale narrative compositions, would have been a considerable undertaking, allowing him to demonstrate his skills in a medium highly valued in Italy. He also painted an altarpiece, The Adoration of the Magi, for the Cybo family chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo, further cementing his reputation in the city.

Beyond these major religious commissions, Van Lint also produced cabinet-sized paintings on religious and mythological themes, often on copper, a support favored for its smooth surface that allowed for fine detail. It was also in Rome that he engaged with the popular genre of Bambocciate – small-scale paintings depicting the everyday life of ordinary people, often peasants, street vendors, and revelers. This genre was pioneered by Dutch painter Pieter van Laer, nicknamed "Il Bamboccio," and his followers, known as the Bamboccianti. Van Lint's foray into this style demonstrates his versatility and responsiveness to prevailing artistic trends.

While in Rome, Van Lint naturally became part of the community of Netherlandish artists residing in the city. He is known to have associated with the Bentvueghels ("birds of a feather"), an informal society of mostly Dutch and Flemish painters, sculptors, and engravers. This group was notorious for its bohemian lifestyle and initiation rituals, but it also provided a crucial network of support and camaraderie for expatriate artists. Figures like Cornelis van Poelenburgh, Bartholomeus Breenbergh, and later Jan Baptist Weenix were part of this milieu. Van Lint also established a connection with Gaspar van Wittel, later known as Vanvitelli, who would become a renowned veduta or cityscape painter. It's plausible that Van Lint's exposure to the clear light and classical ruins of the Roman Campagna, often depicted by artists like Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, also left an impression on his developing style, tempering Flemish exuberance with a more ordered, classical sensibility.

Return to Antwerp and Mature Career

Around 1640, Pieter van Lint returned to his native Antwerp, his artistic vision enriched and his reputation enhanced by his Italian experiences. He re-established himself in the city's vibrant art scene, which, while still feeling the impact of Rubens (who died in 1640), also included prominent figures like Jacob Jordaens, Anthony van Dyck (though often abroad), Cornelis Schut, and Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert. In 1642, he married Elisabeth Willemyns, with whom he would have seven children, some of whom would continue the family's artistic lineage.

Upon his return, Van Lint continued to receive significant religious commissions. He painted altarpieces and other devotional works for churches and private patrons. One notable project involved frescoes for the Cybo family chapel, likely a continuation or a new phase of the patronage initiated in Rome. His style during this mature period reflects a sophisticated fusion: the rich colors, dynamic compositions, and palpable textures of the Flemish tradition were now often structured with a greater sense of classical balance and clarity, a legacy of his Italian years. His figures, while robust, often possess a grace and idealized quality that speaks to his study of both classical sculpture and Italian Renaissance and Baroque masters.

Beyond large-scale religious works, Van Lint was also a sought-after portrait painter. His abilities in this genre earned him international recognition, including commissions from the Danish court to paint portraits of King Christian IV and his family. These works would have required not only a keen ability to capture a likeness but also the skill to convey the sitter's status and authority through pose, costume, and setting. He also continued to produce smaller cabinet paintings, mythological scenes, and possibly further genre pieces, catering to the burgeoning market for art among the affluent bourgeoisie. His versatility extended to tapestry design, a highly valued art form in Flanders, contributing to the region's famed production.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Pieter van Lint's artistic style is best characterized as a harmonious blend of Flemish Baroque energy and Italianate classicism. From his Antwerp training, he inherited a love for rich, saturated colors, a tactile rendering of textures, and a capacity for dynamic, often emotionally charged, compositions. His figures are generally solid and well-modeled, conveying a sense of physical presence.

The years in Italy, however, introduced a strong classicizing element. This is evident in the clarity of his narratives, the often balanced and well-ordered arrangement of his compositions, and a certain idealization in the depiction of human figures, drawing inspiration from classical statuary and High Renaissance masters like Raphael, as well as contemporary classicists like Domenichino or Andrea Sacchi. He did not, however, fully abandon the dynamism of the Baroque; rather, he tempered it with a greater emphasis on structure and decorum. His use of light, while capable of creating dramatic effects, often serves to illuminate the scene clearly, defining forms and enhancing the narrative.

Thematically, Van Lint's oeuvre is dominated by religious subjects, drawn from both the Old and New Testaments, as well as the lives of saints. This focus reflects the enduring importance of the Catholic Church as a patron of the arts, particularly in the Southern Netherlands during the Counter-Reformation. His depictions often aim to be both doctrinally sound and emotionally engaging, encouraging piety and contemplation. Works like The Adoration of the Shepherds or scenes from the Passion of Christ would have been common.

Mythological subjects, often drawn from Ovid's Metamorphoses, also feature in his work, providing opportunities to depict the nude figure and explore themes of love, conflict, and transformation. His portraits, as mentioned, ranged from royal commissions to depictions of local dignitaries or fellow artists, showcasing his ability to capture individual character. The smaller genre scenes, influenced by the Bamboccianti, offered a lighter counterpoint, depicting everyday life with a keen observational eye.

Key Works and Their Characteristics

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné is a subject for ongoing scholarship, several works are consistently attributed to Pieter van Lint and exemplify his style.

His frescoes of the "Legend of the True Cross" for the Ginnasi in Rome, though perhaps not fully extant or easily accessible, represent a major undertaking in a demanding medium. Such narrative cycles required complex compositional skills and the ability to manage multiple figures in coherent and dramatic scenes.

Among his easel paintings, The Adoration of the Magi, painted for the Cybo Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome, would have showcased his ability to handle a traditional religious theme with grandeur and devotion, likely incorporating rich colors and a variety of expressive figures.

Other representative religious works often mentioned include The Beheading of St. John the Baptist, a dramatic subject favored in the Baroque period for its emotional intensity. Abraham's Sacrifice of Isaac is another powerful Old Testament scene he depicted, allowing for the portrayal of profound faith and divine intervention. Jesus and the Samaritan Woman at the Well offers a more contemplative New Testament narrative, focusing on dialogue and spiritual revelation. The Story of Lucretia, a classical theme of virtue and tragedy, would have allowed for a display of historical erudition and dramatic pathos.

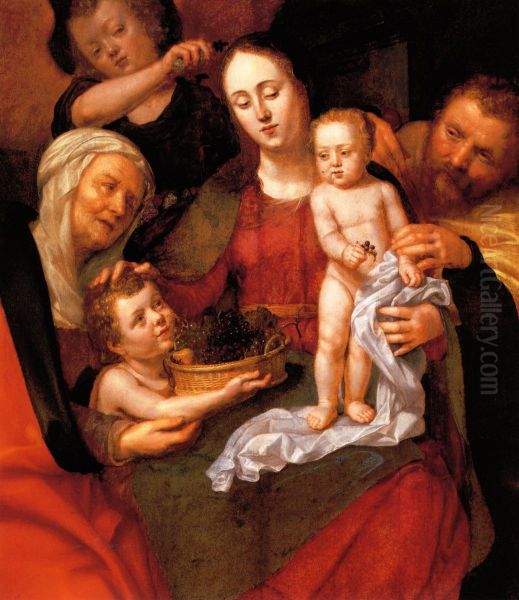

His smaller devotional paintings, often on copper, such as various depictions of the Holy Family or individual saints, are characterized by their meticulous detail, refined finish, and intimate piety. These were highly sought after for private devotion. The quality of his draughtsmanship is also evident in his preparatory drawings, which reveal his working process and compositional thinking. Many of his works, particularly religious scenes, were widely disseminated through prints made after his designs, further extending his influence.

Influence and Legacy

Pieter van Lint's influence during his lifetime was considerable, extending beyond the Southern Netherlands. His works were exported, often through Antwerp's active art market, to Spain, Italy, and even the Spanish colonies in Latin America. This international dissemination speaks to the appeal of his clear narratives, his skillful execution, and his successful fusion of Flemish and Italianate elements. His religious paintings, in particular, resonated with the devotional needs of the Counter-Reformation era.

He also played a role as a teacher. Among his documented pupils were Godfried Maes, Pieter van Mol (who also spent time in Paris), and Jan Baptist Wolfort (son of his own master, Artus Wolffort). Through his students, his stylistic tendencies and working methods would have been perpetuated.

However, in the centuries following his death, Pieter van Lint's distinct artistic personality became somewhat obscured. As with many talented artists who worked in the shadow of giants like Rubens or Van Dyck, some of his works were misattributed. Notably, a number of paintings, particularly those showing a strong Rubenesque influence combined with a certain classical restraint, were sometimes ascribed to Rubens himself in his earlier, more Italianate phase, or to other prominent contemporaries. It was not until the more systematic art historical scholarship of the 20th century, particularly from the 1970s onwards, that dedicated research began to disentangle his oeuvre and re-establish his significance as an independent master. This re-evaluation has led to a greater appreciation of his specific contributions to Flemish and European Baroque art.

His son, Hendrik Frans van Lint (1684-1763), also became a notable painter. Hendrik, often nicknamed "Studio," specialized in Italianate landscapes, particularly views of Rome and its surroundings, in a style reminiscent of Claude Lorrain and Gaspar van Wittel, with whom his father had associated. This demonstrates a continuation of the family's artistic engagement with Italy. Another descendant, Michele Van Lint, is recorded as a sculptor and painter who later settled in Rome, further underscoring the family's artistic inclinations.

Van Lint's Circle: Contemporaries and Students

Understanding Pieter van Lint's place in art history requires acknowledging the network of artists with whom he interacted. His master, Artus Wolffort, provided his initial training. The towering presence of Peter Paul Rubens was an undeniable force in Antwerp, and Van Lint, like all his contemporaries, would have absorbed aspects of Rubens's dynamic style, even while forging his own path. Other Antwerp contemporaries included the prolific Jacob Jordaens, the elegant portraitist and religious painter Anthony van Dyck (though much of his career was spent abroad), and specialists in various genres like Frans Snyders (animals and still life) and Jan Brueghel the Elder and Younger (landscapes and flowers). More direct colleagues in history painting included Cornelis Schut, known for his energetic altarpieces, and Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert, who also worked in a classicizing Baroque style.

In Rome, his circle included the Bentvueghels, a diverse group of Northern artists. His association with Gaspar van Wittel was significant, as Van Wittel became a foundational figure in Italian view painting. The dominant Italian figures of the time, such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Pietro da Cortona, Andrea Sacchi, and the French classicists Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, formed the artistic environment in which Van Lint developed his Italianate tendencies.

His students, including Pieter van Mol, who later had a successful career in Paris, and Godfried Maes, carried his teachings forward. The fact that Jan Baptist Wolfort, the son of his own master, also studied with him suggests a respected position within the Antwerp artistic community.

Family and Artistic Dynasty

The Van Lint family demonstrated a notable artistic continuity. Pieter van Lint's marriage to Elisabeth Willemyns produced a large family. While not all his children pursued artistic careers, the most prominent was his son, Hendrik Frans van Lint. Born in Antwerp in 1684, Hendrik Frans moved to Rome around 1700 and remained there for the rest of his life, becoming a highly successful painter of vedute (cityscapes and topographical views). His meticulous, light-filled landscapes earned him the nickname "Studio" (study), possibly due to his detailed preparatory work. His style shows the clear influence of artists like Claude Lorrain and Gaspar van Wittel, the latter a known associate of his father. Hendrik Frans's success in this genre highlights how the family's connection to Italy and its artistic traditions was maintained and transformed in the next generation. The mention of Michele Van Lint as a sculptor and painter in Rome further suggests a persistent artistic vein within the family.

Conclusion: A Reappraised Master

Pieter van Lint emerges from the annals of art history as a highly skilled and versatile Flemish Baroque painter whose career successfully bridged the artistic worlds of Antwerp and Rome. His ability to absorb and synthesize diverse influences – the dynamism of his native Flemish tradition, the classical ideals encountered in Italy, and the popular genre conventions of his time – resulted in an oeuvre characterized by narrative clarity, refined execution, and considerable emotional depth.

While his fame may have been temporarily eclipsed by some of his more celebrated contemporaries, and his works sometimes misattributed, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized his distinct contribution. From grand religious frescoes and altarpieces to intimate devotional paintings, insightful portraits, and engaging genre scenes, Van Lint demonstrated a consistent level of quality and adaptability. His international patronage and the dissemination of his works attest to his contemporary appeal. As an artist who navigated the complex artistic currents of the 17th century with skill and intelligence, Pieter van Lint rightfully claims his place as an important master within the rich tradition of European Baroque painting. His legacy endures not only in his own diverse body of work but also through the artistic endeavors of his descendants, particularly his son Hendrik Frans, who carried the family's artistic engagement with Italy into the 18th century.