Giovanni Lanfranco stands as a pivotal figure in the transition from the late Mannerist and early Baroque styles fostered by the Carracci academy to the full-blown High Baroque aesthetic that would dominate Italian art in the 17th century. Born in Parma in 1582 and active primarily in his hometown, Rome, and Naples before his death in Rome in 1647, Lanfranco became renowned for his dynamic and illusionistic fresco decorations, particularly those adorning church domes. His work synthesized the structural solidity learned from the Carracci with the dramatic lighting of Caravaggio and, most significantly, the breathtaking spatial illusionism pioneered by Correggio, creating a powerful and influential style that left an indelible mark on the course of Baroque art.

Parma Roots and Early Training

Giovanni Lanfranco entered the world near Parma, a city already steeped in a rich artistic heritage, most notably that of Antonio Allegri da Correggio. Born the third son of Stefano and Cornelia Lanfranchi, young Giovanni showed an early aptitude for art. His talent did not go unnoticed. According to early biographers like Giovanni Pietro Bellori, Lanfranco initially served as a page in the household of Count Orazio Scotti in Piacenza. Recognizing the boy's artistic inclinations, Scotti arranged for him to study under the Bolognese master Agostino Carracci, who was then active in Parma, working for Duke Ranuccio I Farnese.

This apprenticeship, beginning around 1597/98 and continuing intermittently until Agostino's untimely death in 1602, was formative. Agostino, alongside his brother Annibale and cousin Ludovico Carracci, had spearheaded a reform movement in Italian painting, advocating a return to naturalism, clear composition, and the study of High Renaissance masters, reacting against the perceived artificiality of late Mannerism. Under Agostino's guidance, Lanfranco would have absorbed the fundamentals of drawing, composition, and the Carracci emphasis on life study. During this period, he likely worked alongside another promising student, Sisto Badalocchio, also from Parma, with whom he would later collaborate. An early display of his burgeoning skill was a painting of the Madonna and Saints, reportedly created when he was just sixteen and placed in the Church of Sant'Agostino in Piacenza, earning considerable praise.

The Move to Rome and the Carracci Workshop

Following Agostino Carracci's death in 1602, the Duke of Parma, Ranuccio I Farnese, recognizing Lanfranco's potential, sent him and Sisto Badalocchio to Rome to continue their training under Agostino's brother, the celebrated Annibale Carracci. This move placed Lanfranco at the very heart of the Italian art world, within one of the most influential workshops of the era. Annibale was then completing his masterpiece, the ceiling frescoes of the Galleria Farnese in the Palazzo Farnese, a landmark work that synthesized classical ideals with Venetian color and a vibrant naturalism.

Working under Annibale, Lanfranco joined a talented group of young artists who were assisting the master and absorbing his style. This circle included figures who would become major painters in their own right, such as Domenichino (Domenico Zampieri), Guido Reni, and Francesco Albani. Lanfranco participated in the decoration of the Farnese Palace and also contributed, alongside his colleagues, to the decoration of the Herrera Chapel in San Giacomo degli Spagnoli (completed around 1607). This period provided invaluable experience in large-scale fresco painting and exposed him to the monumental classicism and sophisticated narrative techniques favored by Annibale. The Carracci workshop emphasized rigorous drawing (disegno) and a balanced, ordered approach to composition, principles that would remain foundational even as Lanfranco developed his own distinct manner.

Forging an Independent Style: Correggio and Caravaggio

While deeply indebted to the Carracci, Lanfranco soon began to forge a more personal and dynamic style. A crucial catalyst was his deep admiration for the art of his fellow Parmese, Correggio. Correggio's revolutionary illusionistic dome frescoes in Parma Cathedral and San Giovanni Evangelista, with their swirling vortexes of figures ascending into heavenly light using dramatic foreshortening (di sotto in sù – "from below, upwards"), left a profound impression on Lanfranco. He saw in Correggio a path towards a more emotive, spatially complex, and visually overwhelming form of religious art than the more restrained classicism often favored by Annibale's immediate followers like Domenichino.

Simultaneously, Lanfranco absorbed lessons from another giant of the Roman art scene: Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. While not directly associated with Caravaggio, Lanfranco could not ignore the powerful impact of his dramatic chiaroscuro (strong contrasts of light and shadow) and intense, often gritty, realism. Lanfranco began to incorporate a heightened sense of drama, dynamic movement, and strong lighting effects into his work, moving away from the more evenly lit and classically composed scenes typical of the core Carracci tradition. This fusion of Correggio's spatial illusionism and Caravaggio's dramatic intensity, built upon a Carraccesque foundation, became the hallmark of Lanfranco's mature style. Early independent commissions, such as decorations in the Palazzo Mattei and work for the Borghese family, began to showcase this evolving approach.

Master of the Roman Dome: Sant'Andrea della Valle

Lanfranco's breakthrough and arguably his most influential work came with the commission to decorate the massive dome of the Theatine church of Sant'Andrea della Valle in Rome. Secured around 1621 and completed between 1625 and 1627, the fresco depicts the Assumption of the Virgin (or Glory of Paradise). This vast composition marked a definitive arrival of the High Baroque ceiling style, directly challenging the more classical approach. Drawing explicitly on Correggio's Parma domes, Lanfranco created a swirling, ecstatic vortex of apostles, saints, and angels spiraling upwards towards the divine light, with the Virgin Mary ascending at the center.

The effect is one of overwhelming energy and boundless space, seemingly dissolving the physical architecture of the dome into a vision of heaven. The use of di sotto in sù is masterful, making the figures appear to float and tumble realistically within the celestial sphere. The vibrant color and dramatic lighting further enhance the scene's emotional impact. This work stood in stark contrast to the pendentives below the dome, which depicted the Four Evangelists and had been painted shortly before (1622-1627) by Lanfranco's contemporary and rival, Domenichino. Domenichino's figures are classically composed, stable, and clearly delineated, representing the more conservative, Raphaelesque tradition stemming from Annibale Carracci. The juxtaposition within the same church highlighted the diverging paths of Baroque painting, with Lanfranco championing a more dynamic, illusionistic, and emotionally charged aesthetic. The Sant'Andrea dome became a benchmark for large-scale ceiling decoration for decades to come.

High Baroque Commissions and Context

The success at Sant'Andrea della Valle solidified Lanfranco's position as a leading painter in Rome. He received numerous important commissions during this period. He contributed paintings to St. Peter's Basilica, including an altar painting (later replaced by a mosaic copy) of Christ Walking on the Water (the Navicella) for the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament, commissioned by Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini). He also painted frescoes depicting scenes from the life of Christ for the Chapel of the Crucifix (or Blessed Sacrament) in San Paolo fuori le Mura (St. Paul Outside the Walls) around 1621-1624, including the notable Moses and the Messengers from Canaan.

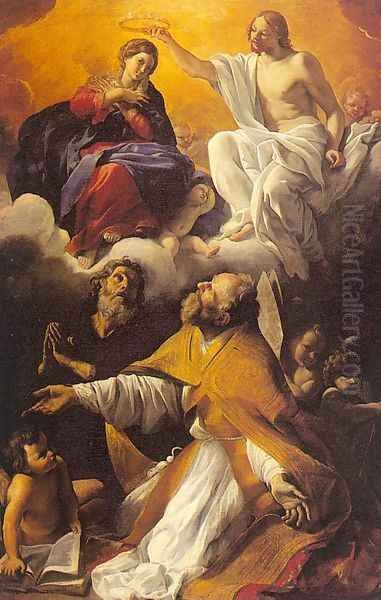

His work placed him at the forefront of the developing High Baroque style, alongside contemporaries like Pietro da Cortona, whose own spectacular ceiling fresco in the Palazzo Barberini (1633-1639) would further define the era's taste for grand illusionism. While Lanfranco's style was perhaps less overtly decorative than Cortona's, his focus on dramatic narrative and spatial depth was highly influential. He navigated the complex patronage systems of papal Rome, working for powerful families like the Borghese and Barberini, and religious orders like the Theatines. His ability to manage large-scale fresco projects efficiently made him a sought-after artist for major decorative cycles. He was also active in easel painting, producing altarpieces and devotional works characterized by the same dynamic energy and lighting found in his frescoes, such as The Stigmatization of Saint Francis of Assisi.

Navigating Rivalries in Rome

The artistic environment of 17th-century Rome was intensely competitive. Patronage was plentiful, but so were talented artists vying for the most prestigious commissions. Lanfranco found himself in direct competition not only with Domenichino but also with other leading figures like Guido Reni and Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri). The rivalry with Domenichino was particularly acute and sometimes bitter.

Beyond the stylistic differences evident at Sant'Andrea della Valle, the competition occasionally spilled into accusations. Lanfranco and his supporters were reportedly involved in criticizing Domenichino's acclaimed altarpiece, The Last Communion of St. Jerome (painted 1614), alleging it plagiarized an earlier work on the same theme by Agostino Carracci. While the extent of Lanfranco's personal involvement in spreading these rumors is debated by historians, the incident reflects the high stakes and intense pressures faced by artists. Lanfranco's success in securing the Sant'Andrea dome commission over Domenichino, despite the latter having already begun work on the pendentives, was a major coup achieved through skillful maneuvering and the appeal of his more dynamic, modern style to the patrons. This competitive spirit, while sometimes acrimonious, also spurred innovation and pushed artists to excel.

Dominating the Neapolitan Scene

Around 1634, Lanfranco moved to Naples, where he would spend over a decade (until 1646) and execute some of his most significant works. Naples was a major European metropolis and a vibrant artistic center, though its style had been heavily influenced by the tenebrism of Caravaggio (who had worked there) and his followers, notably the Spanish painter Jusepe de Ribera. Lanfranco brought the grand manner of Roman High Baroque fresco painting to the city, introducing a brighter palette and more complex illusionistic schemes than were typical of the prevailing Neapolitan Caravaggism.

His first major Neapolitan commission was the decoration of the dome of the Gesù Nuovo church (1634-35). However, his most prestigious and challenging project was the decoration of the dome of the Cappella del Tesoro di San Gennaro (Chapel of the Treasury of St. Januarius) in Naples Cathedral. This commission had previously been held by Domenichino, who died in 1641, allegedly amidst difficulties and possibly even threats from jealous local artists (the so-called "Cabal of Naples," though the extent and nature of this group are debated). Lanfranco took over and completed the stunning dome fresco depicting the Glory of Paradise between 1641 and 1643. He also painted frescoes in other major Neapolitan sites, including the Certosa di San Martino (Church and Choir Vaults, 1637-38) and the church of Santi Apostoli (Vaults, 1638-1646). His Neapolitan works often display an even greater luminosity and freedom of handling than his Roman frescoes, profoundly influencing the next generation of Neapolitan painters. He worked alongside prominent local artists like Massimo Stanzione, contributing significantly to the development of the Neapolitan Baroque.

Late Works and Return to Rome

Having dominated the Neapolitan fresco scene for over a decade, Lanfranco returned to Rome in 1646. Though nearing the end of his life, he remained active. One of his final significant commissions was for the apse of San Carlo ai Catinari, where he painted the Apotheosis of St. Charles Borromeo. His last documented painting is The Call of St. Matthew, executed in 1646 and housed in the Casa di Riparazione at the Palazzo Boschi.

Giovanni Lanfranco died in Rome on November 30, 1647, at the age of 65. He left behind a substantial body of work that had significantly shaped the visual language of the Italian Baroque. His career trajectory, from Parma through the crucible of the Carracci workshop in Rome to his dominance in Naples and final return to Rome, mirrors the evolution and dissemination of Baroque style itself.

Signature Style and Techniques

Giovanni Lanfranco's artistic signature lies in his powerful synthesis of diverse influences into a coherent and dynamic Baroque style. His primary medium for large-scale works was fresco, a technique he mastered with remarkable skill and efficiency, allowing him to cover vast architectural surfaces. Key elements of his style include:

1. Correggesque Illusionism: His most defining characteristic, particularly in dome frescoes, was the use of di sotto in sù perspective to create breathtaking illusions of figures ascending or swirling within an infinite heavenly space, effectively dissolving the architectural boundary.

2. Dramatic Chiaroscuro: Influenced by Caravaggio, Lanfranco employed strong contrasts between light and shadow to heighten drama, model forms powerfully, and direct the viewer's eye.

3. Dynamic Composition: Rejecting static, classical arrangements, his compositions are typically characterized by energetic movement, swirling diagonals, and complex groupings of figures that convey intense emotion and activity.

4. Vibrant Color: While capable of somber tones, especially in some easel paintings, his frescoes often feature rich, vibrant colors that contribute to the overall spectacle and emotional intensity, particularly evident in his Neapolitan works.

5. Emotional Intensity: Whether depicting ecstatic saints, dramatic martyrdoms, or divine apparitions, Lanfranco imbued his figures with palpable emotion, engaging the viewer on a visceral level, in line with the persuasive goals of Counter-Reformation art.

6. Carraccesque Foundation: Underlying the dynamism and drama was a solid grounding in drawing and structure learned from the Carracci, which prevented his compositions from dissolving into chaos.

Enduring Legacy and Influence

Giovanni Lanfranco's impact on the development of Baroque art was profound and lasting. While he apparently did not run a large workshop or have many documented direct pupils in the way some contemporaries did, his influence was disseminated through the sheer power and visibility of his major works.

His Sant'Andrea della Valle dome became a foundational model for High Baroque ceiling painting in Rome and beyond, inspiring subsequent generations of artists tackling similar architectural challenges. Artists like Pietro da Cortona certainly looked to Lanfranco's example, even as they developed their own variations on grand ceiling decoration. Later masters of illusionistic ceiling painting, such as Andrea Pozzo, built upon the tradition that Lanfranco had so powerfully advanced.

In Naples, his impact was arguably even more direct and transformative. His introduction of Roman High Baroque grandeur, combined with a brighter palette and dynamic composition, offered a compelling alternative to the prevailing Caravaggism. He directly influenced the leading figures of the Neapolitan Baroque, including Luca Giordano, Francesco Solimena, and Mattia Preti. These artists absorbed Lanfranco's lessons in large-scale fresco decoration, dynamic movement, and dramatic lighting, integrating them into their own styles and ensuring the continuation of a vibrant Baroque tradition in Southern Italy well into the 18th century. Lanfranco is thus rightly considered not just a master in his own right, but a crucial catalyst in the evolution and spread of the Italian Baroque aesthetic.

Conclusion

Giovanni Lanfranco emerges from the historical narrative as a vital force in 17th-century Italian art. Trained in the reformist environment of the Carracci, he boldly synthesized their principles with the revolutionary spatial concepts of Correggio and the dramatic intensity of Caravaggio. His daring illusionistic dome frescoes, particularly the Assumption in Sant'Andrea della Valle, redefined the possibilities of architectural decoration and set a standard for the High Baroque. Through his prolific activity in Rome and Naples, he not only created masterpieces of dramatic religious art but also profoundly influenced his contemporaries and successors, particularly in the realm of large-scale fresco painting. As a master technician, a powerful visual storyteller, and a key innovator, Giovanni Lanfranco secured his place as one of the indispensable pioneers of the Italian Baroque.