The annals of art history are replete with celebrated masters whose lives and works have been meticulously documented and analyzed. Yet, alongside these luminaries exist countless other artists, individuals who contributed to the rich tapestry of their era but whose stories remain partially veiled, awaiting fuller discovery. Gustave Barrier, an artist presumed to have been active in France with a lifespan indicated as 1871 to 1953, appears to be one such enigmatic figure. While concrete biographical information and a comprehensive catalogue of his works are not widely accessible, the mention of specific art pieces attributed to him allows us to begin sketching a portrait, however incomplete, and to place him within the vibrant artistic milieu of his time.

The Challenge of Biographical Reconstruction

Pinpointing the precise details of Gustave Barrier's life presents a considerable challenge. Standard art historical databases and biographical dictionaries yield scant specific information for a painter named Gustave Barrier with the life dates 1871-1953. This scarcity itself is noteworthy, suggesting perhaps a career that was modest in public recognition, or one whose works primarily resided in private collections, or an artist active in a regional center away from the main currents of Paris, which dominated the French art scene.

The period of his supposed activity, spanning the late 19th and first half of the 20th century, was a time of unprecedented artistic upheaval and innovation in France. Artists were breaking from academic traditions, exploring new ways of seeing and representing the world. If Gustave Barrier was indeed born in 1871, he would have come of age during the zenith of Impressionism and the rise of Post-Impressionism. His formative years as an artist would have coincided with the emergence of Fauvism, Cubism, and subsequently Surrealism and various forms of abstraction. This dynamic environment offers a vast spectrum of potential influences and stylistic paths he might have pursued.

It is also crucial to distinguish Gustave Barrier from other individuals with similar surnames who were prominent in artistic or related fields, as confusion can easily arise. For instance, George Barbier (1882-1932) was a celebrated French illustrator, theatre and fashion designer, a prominent figure in the Art Deco movement. His elegant, stylized work is distinct and well-documented. Another figure, Auguste Barbier (1805-1882), was a 19th-century French poet, known for his satirical verse, whose connection to the visual arts might be through literary themes or collaborations, but he belongs to an earlier generation. There is also mention of a Dominique Barlier, a French printmaker active in the 19th century, primarily in Rome. These individuals, while bearing similar names, operate in different spheres or timeframes from the Gustave Barrier in question.

The name "Gustave Barrier" also appears in non-artistic contexts, such as a co-author or translator for the academic work "The exterior of the horse." This further complicates the search for the artist, highlighting the need to carefully sift through records. However, the critical piece of evidence affirming his identity as an artist comes from auction records listing works by a Gustave Barrier, specifically still life paintings.

Artistic Milieu: France from 1871 to 1953

To understand the potential artistic identity of Gustave Barrier, one must consider the world he inhabited. France, particularly Paris, was the undisputed capital of the art world during much of his lifetime.

The Legacy of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism:

Born in 1871, Barrier's childhood and youth would have been set against the backdrop of Impressionism's revolutionary impact. Artists like Claude Monet (1840-1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), and Edgar Degas (1834-1917) had already challenged the Salon system with their focus on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and color, and scenes of modern life.

By the time Barrier might have been embarking on artistic training, Post-Impressionism was in full swing. Figures such as Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), with his structured, analytical approach to form and space; Vincent van Gogh (1853-1990), with his expressive use of color and brushwork; Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), with his Synthetist style and exploration of primitivism; and Georges Seurat (1859-1891), with his scientific Pointillism, were all pushing the boundaries of painting in diverse directions. These movements fundamentally altered the course of Western art and would have been unavoidable influences or points of departure for any aspiring artist in France.

The Dawn of Modernism: Fauvism and Cubism:

As the 20th century began, the pace of innovation quickened. The Salon d'Automne of 1905 witnessed the explosive arrival of Fauvism, led by Henri Matisse (1869-1954) and André Derain (1880-1954). Their bold, non-naturalistic use of color, prioritizing emotional expression over descriptive accuracy, shocked many but signaled a new era of freedom.

Shortly thereafter, Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Georges Braque (1882-1963), fractured and reassembled objects and figures, challenging traditional perspective and representation. This intellectual and analytical approach had profound implications for the future of art. The development of Cubism, through its Analytic and Synthetic phases, opened doors to further abstraction.

Art Nouveau and Art Deco:

Concurrent with these avant-garde painting movements, decorative arts also flourished. Art Nouveau, with its organic, flowing lines, was prominent at the turn of the century, influencing artists like Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) in Austria and Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939) in Paris. This style gave way to Art Deco in the 1920s and 1930s, characterized by geometric forms, rich materials, and a sense of streamlined elegance. As mentioned, George Barbier was a master of the Art Deco style in illustration and design. While Gustave Barrier is identified as a painter of still lifes, the pervasive aesthetic of these decorative movements could have subtly informed his sense of composition or palette.

Between the Wars and Beyond: Surrealism and Continued Figuration:

The period between the World Wars saw the rise of Surrealism, heavily influenced by Freudian psychology, with artists like Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) and René Magritte (1898-1967) exploring the world of dreams and the subconscious. Simultaneously, many artists continued to work in figurative styles, sometimes inflected by modernism, sometimes adhering more closely to tradition. The "Return to Order" (Rappel à l'ordre) was a notable trend in the 1920s, where artists previously associated with the avant-garde adopted more classical approaches. Artists like André Dunoyer de Segonzac (1884-1974) or Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964) in Italy, a master of meditative still lifes, showed that figuration and modern sensibility were not mutually exclusive.

This rich and varied artistic landscape provided a complex array of choices for an artist like Gustave Barrier. He could have aligned himself with one of the avant-garde movements, remained a more traditional academic painter, or forged a personal style that synthesized various influences.

Gustave Barrier’s Known Works: A Glimpse Through Still Life

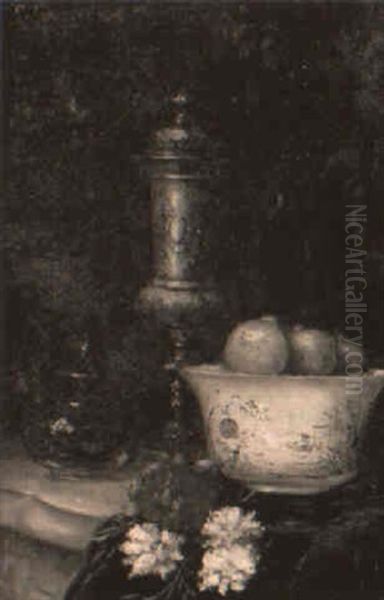

The most concrete evidence of Gustave Barrier's artistic practice comes from the titles of two works that have appeared in auction contexts: Nature morte aux citrons (Still Life with Lemons) and Nature morte à la coupe et à la louche (Still Life with Bowl and Ladle). These titles firmly place him within the venerable tradition of still life painting.

The genre of still life (nature morte, literally "dead nature," in French) has a long and distinguished history in European art. It gained prominence as an independent genre in the Netherlands during the 17th century with artists like Willem Kalf (1619-1693) and Clara Peeters (1594-c. 1657), who created lavish displays (pronkstilleven) or more modest "breakfast pieces." In France, Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699-1779) elevated still life to a high art form in the 18th century, imbuing humble domestic objects with quiet dignity and profound painterly skill. His work was admired by later artists, including Édouard Manet (1832-1883) and Cézanne.

Throughout the 19th century, still life continued to be a subject for academic painters as well as innovators. The Impressionists often included still life elements in their broader compositions or painted them as standalone subjects, exploring light and color. For Cézanne, still life was a crucial vehicle for his investigations into form, structure, and the nature of perception. His still lifes, with their carefully arranged fruits, pitchers, and drapery, are landmarks of modern art, demonstrating how the genre could be a site for radical formal experimentation. Van Gogh also produced powerful still lifes, such as his iconic "Sunflowers," charged with emotional intensity.

By choosing to paint still lifes, Gustave Barrier was engaging with this rich heritage. The titles Nature morte aux citrons and Nature morte à la coupe et à la louche suggest traditional subject matter. Lemons, with their vibrant yellow, have been a favorite motif for still life painters for centuries, offering a strong color accent and an interesting texture. Bowls and ladles are common domestic items, staples of the kitchen still life tradition popularized by Chardin.

Without visual access to these paintings, it is difficult to ascertain Barrier's specific style.

Did he adopt a traditional, realistic approach, focusing on meticulous rendering and the play of light on surfaces, in the vein of the Dutch masters or Chardin?

Was his style influenced by Impressionism, with a concern for capturing the optical effects of light and color through broken brushwork?

Did he, like Cézanne, use still life as a means to explore underlying geometric forms and spatial relationships?

Or perhaps his work reflected later trends, perhaps a more Fauvist palette or a simplified, modern sensibility akin to some of Morandi's introspective compositions?

The period 1871-1953 allows for any of these possibilities. An artist working in the early part of this timeframe might lean towards late Impressionism or a more academic style, while someone active into the mid-20th century could have incorporated elements of Cubism, Fauvism, or even a subtle abstraction while remaining within the still life genre. The very choice of still life could indicate a temperament inclined towards contemplation, a focus on the formal qualities of painting, or an appreciation for the beauty of everyday objects.

Potential Artistic Affiliations and Influences

Given the lack of direct information about Gustave Barrier's training, exhibitions, or artistic circle, we can only speculate about his affiliations. If he trained in Paris, he might have attended the École des Beaux-Arts, which, despite the rise of the avant-garde, remained a bastion of academic tradition. Alternatively, he could have studied at one of the independent academies like the Académie Julian or the Académie Colarossi, which were more receptive to modern ideas and attracted students from around the world.

His choice of still life might suggest an affinity for artists who excelled in this genre. Beyond Chardin and Cézanne, he might have looked to contemporaries who specialized in or frequently painted still lifes. For example, Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904) was renowned for his exquisite floral still lifes, painted in a sensitive, realistic manner that also appealed to a modern sensibility. The Intimist painters Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) and Édouard Vuillard (1868-1940), though often associated with domestic interiors and figures, also produced remarkable still lifes that are integral to their compositions, characterized by rich color harmonies and decorative patterning. Barrier, as a contemporary of Bonnard and Vuillard, might have shared some of their sensibilities if his work leaned towards a more intimate and color-focused approach.

If Barrier's still lifes were more modern in execution, he might have been aware of the Cubist still lifes of Picasso, Braque, or Juan Gris (1887-1927), which deconstructed objects into geometric planes. Or, if his work possessed a vibrant chromatic intensity, the influence of Fauvist painters like Matisse or Derain could be considered. Matisse, throughout his long career, repeatedly returned to the still life, using it as a vehicle for his explorations of color, line, and decorative harmony.

The very fact that Barrier's known works are still lifes could also suggest a more independent path, perhaps an artist working somewhat outside the main exhibiting societies or avant-garde groups, focusing on a genre that allows for quiet study and personal expression without necessarily engaging with the more radical or public declarations of some modernist movements.

The Enigma of Gustave Barrier: A Legacy in Shadow

The case of Gustave Barrier underscores a common reality in art history: for every artist whose name becomes a household word, there are many others whose contributions are less visible. Their works may be held in private hands, their exhibition history may be limited, or they may have been overshadowed by more assertive or revolutionary contemporaries.

The dates 1871-1953 place Gustave Barrier squarely within one of the most fertile and transformative periods in the history of art, particularly in France. He would have witnessed the full flowering of modernism, from its Impressionist roots to the diverse movements of the early and mid-20th century. His choice of still life as a subject connects him to a long and respected tradition, one that has been continually revitalized by artists seeking to explore the fundamental elements of painting: form, color, light, and composition.

The two painting titles, Nature morte aux citrons and Nature morte à la coupe et à la louche, offer tantalizing but limited clues. They speak of an engagement with the tangible world, with the simple objects of daily life. Without further information or visual evidence of his work, it is challenging to paint a more complete picture of Gustave Barrier's artistic identity, his stylistic evolution, or his place within the broader currents of French art.

He remains an enigmatic figure, a name associated with a classic genre, active during a period of profound artistic change. Perhaps future research, the discovery of more works, or the emergence of archival material will shed further light on Gustave Barrier, allowing art historians to more fully appreciate his contribution and to move his story from the shadows into a clearer historical narrative. Until then, he serves as a reminder of the vast, often unrecorded, artistic activity that underpins the more visible peaks of art history, and the quiet dedication of artists who, like him, found their voice in the enduring language of painting.