Jules Frederic Ballavoine stands as an intriguing, if somewhat enigmatic, figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. A Parisian by birth and training, he navigated the bustling art world of his time, achieving recognition within the established Salon system. Primarily known for his graceful depictions of young women, genre scenes, and historical subjects, Ballavoine's work embodies a particular aesthetic of the era, blending academic polish with a sensitivity to contemporary life and fashion. However, his legacy is complicated by significant uncertainty regarding his precise lifespan, with historical records offering conflicting dates for his birth and death.

Despite these biographical ambiguities, Ballavoine's identity as a French artist is undisputed. He was deeply rooted in the artistic milieu of Paris, the undisputed center of the Western art world during his active years. His participation in the Paris Salon, the most important official art exhibition of its time, confirms his engagement with the mainstream art establishment. His art, often characterized by its delicate execution and poetic sensibility, offers a window into the tastes and preoccupations of the Belle Époque.

The very dates of Ballavoine's existence remain a subject of debate among art historians, a peculiar situation for an artist who achieved a measure of success in his lifetime. Some sources place his birth in 1833 and his death in 1903. Others propose the dates 1845-1914, suggesting a slightly later period of activity. Yet another set of records indicates a lifespan from 1842 to 1901. This lack of consensus highlights the challenges in reconstructing the lives of artists who, while recognized, did not attain the level of fame that invites exhaustive documentation, unlike contemporaries such as Claude Monet or Auguste Rodin. These discrepancies inevitably affect our understanding of his career trajectory and his relationship to specific art movements.

Parisian Roots and Artistic Formation

Born in Paris, Jules Frederic Ballavoine grew up immersed in the city's vibrant cultural atmosphere. The latter half of the 19th century was a period of immense artistic ferment in the French capital, witnessing the decline of Neoclassicism, the rise and evolution of Realism, the revolutionary emergence of Impressionism, and the diverse currents of Post-Impressionism and Symbolism. It was within this dynamic environment that Ballavoine sought his artistic education.

Evidence suggests he received formal training, reportedly studying at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. This institution was the bastion of academic tradition, emphasizing rigorous drawing skills, the study of classical antiquity and Renaissance masters, and the hierarchy of genres, which placed historical painting at the apex. Training at the École would have provided Ballavoine with a solid foundation in anatomy, perspective, and composition, skills evident in the polished finish of many of his works.

However, specific details about his teachers or mentors at the École are scarce in readily available records. Unlike artists such as Henri Matisse, whose tutelage under Gustave Moreau is well-documented, or the Impressionists who often shared teachers like Charles Gleyre (though they later rebelled against his methods), Ballavoine's precise pedagogical lineage remains somewhat obscure. This lack of detail contributes to the difficulty in fully mapping his early influences and artistic development, separating him from figures whose formative years are more clearly understood.

The Paris Salon: Debut and Recognition

The Paris Salon was the essential arena for any ambitious artist in 19th-century France. Organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts for much of the century, it was an annual (or biennial) exhibition that could make or break careers. Acceptance into the Salon signified official approval and provided artists with crucial visibility, connecting them with critics, dealers, and potential patrons. Rejection, famously experienced by Édouard Manet with his "Déjeuner sur l'herbe," could lead to notoriety or marginalization.

Ballavoine successfully navigated this system. He made his debut at the Salon in 1877. This initial acceptance was a significant milestone, indicating that his work met the standards of the jury, which typically favored polished execution and conventional subject matter. His continued participation in the Salon throughout the following years demonstrates his commitment to engaging with the official art world, even as alternative exhibition venues, like the Impressionist exhibitions (held between 1874 and 1886), challenged the Salon's dominance.

His persistence paid off. In 1886, Ballavoine was awarded a medal at the Salon. Receiving such an honor was a mark of distinction, elevating his status and likely enhancing his reputation among collectors. This award suggests that his work resonated with the prevailing tastes of the time, finding favor with a jury that included established academic painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau or Jean-Léon Gérôme, known for their own highly finished, often idealized depictions. The medal solidified Ballavoine's position as a competent and recognized painter within the mainstream.

Artistic Style: Academicism, Realism, and Impressionist Whispers

Characterizing Ballavoine's style presents certain complexities, reflecting the eclectic nature of art during his era. His work is often situated within the broad category of academic painting, given his training and Salon participation. This is evident in the careful drawing, smooth finish, and often idealized representation of his subjects, particularly his female figures. The term "academic" in this context refers to art that adheres to the principles taught in the official academies, emphasizing tradition and technical skill.

However, his style is not purely academic in the mold of strict Neoclassicists like Jacques-Louis David from an earlier generation, or even the high academicism of Cabanel. There are elements that connect his work to Realism, particularly in his choice of contemporary genre subjects – scenes of everyday Parisian life, moments of quiet domesticity, or fashionable women engaged in leisure activities. This focus on the modern world aligns him, in theme at least, with Realists like Gustave Courbet, though Ballavoine generally avoided the overt social commentary or gritty portrayal of labor found in Courbet's work.

Intriguingly, some descriptions of his art suggest a fusion or influence of Impressionism and even Pointillism. This claim requires careful consideration. While Ballavoine was active during the height of Impressionism, his typical style does not fully embrace its core tenets – the broken brushwork, the emphasis on capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere en plein air, or the dissolution of form. However, he does demonstrate a clear interest in light and color. His palettes could be bright and vibrant, used to convey a sense of liveliness, or employ softer, more modulated tones for contemplative scenes. It's possible he absorbed certain aspects of the Impressionist approach to color and light without adopting their radical techniques wholesale, perhaps akin to painters like Alfred Stevens or James Tissot, who depicted modern life with academic precision but a heightened sensitivity to contemporary fashion and atmosphere.

The suggestion of Pointillism, the technique of applying small dots of color associated with Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, seems less likely to be a dominant feature of Ballavoine's main body of work, which generally favors smoother blending. However, it's conceivable that he experimented with different techniques or that certain passages in his paintings might exhibit a more broken application of color that observers interpreted through the lens of burgeoning Post-Impressionist methods. His style might be best described as a refined academic realism, softened by a poetic sensibility and occasionally brightened by an awareness of Impressionist color palettes.

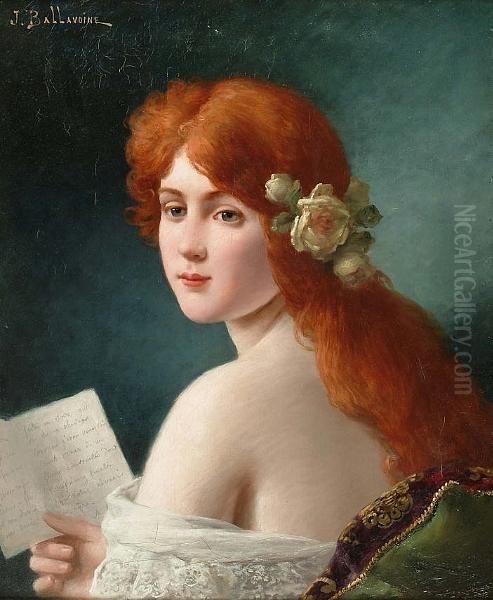

The Allure of the Parisian Woman

A recurring and perhaps the most characteristic theme in Jules Frederic Ballavoine's oeuvre is the depiction of young, elegant Parisian women. These figures are often shown in intimate domestic settings, during moments of leisure, or adorned in fashionable attire. They might be captured reading a letter, arranging flowers, gazing into a mirror, holding a fan, or simply presenting themselves to the viewer with a demure or engaging look. These works catered to a specific taste prevalent during the Belle Époque – a fascination with feminine beauty, grace, and the nuances of modern life.

His approach to these subjects was typically delicate and idealized. While grounded in realistic observation of costume and setting, his figures often possess a porcelain-like smoothness and an air of gentle refinement. This contrasts sharply with the more psychologically probing or socially critical depictions of women by contemporaries like Edgar Degas (with his dancers and laundresses) or Édouard Manet (with figures like Olympia or the barmaid at the Folies-Bergère). Ballavoine's women inhabit a world of comfort, elegance, and quiet contemplation.

Works like "Le Bouquet de Violettes" (The Bouquet of Violets) or "La Séance Interrompue" (The Interrupted Sitting), likely depicting an artist's model taking a break, exemplify this focus. They showcase his skill in rendering textures – the sheen of silk, the softness of feathers, the delicacy of flowers – and in capturing subtle expressions. These paintings were popular with bourgeois collectors who appreciated their charm, technical polish, and affirmation of contemporary ideals of femininity and domesticity. They align Ballavoine with other successful Salon painters who specialized in similar themes, creating images that were both aesthetically pleasing and socially reassuring.

Representative Works: Glimpses into Ballavoine's World

While the provided source material lamented the difficulty in identifying specific representative works, further investigation reveals several paintings frequently associated with Jules Frederic Ballavoine that exemplify his style and thematic concerns. Pinpointing definitive "masterpieces" remains challenging, as his reputation rests more on a consistent output of charming genre scenes and portraits rather than landmark individual works that redefined artistic practice.

"La Séance Interrompue" is often cited. It typically depicts a young woman, presumably an artist's model, in a state of partial undress within a studio setting, perhaps looking thoughtfully away or engaging with something outside the picture frame. The title suggests a narrative moment, adding a layer of gentle intrigue. The execution usually showcases Ballavoine's skill in rendering flesh tones, fabrics, and the studio environment with academic finesse.

"Le Bouquet de Violettes" is another characteristic example, often featuring a stylishly dressed young woman holding or admiring a small bouquet of violets. Violets carried symbolic meanings in the 19th century, often associated with modesty or remembrance. Such works combine portraiture with genre elements and still life, highlighting Ballavoine's versatility in handling different textures and details, from the woman's attire to the delicate flowers.

Other titles that appear associated with him include "Une Parisienne" (A Parisian Woman), "The Fan," "Young Woman with a Mirror," and portraits simply titled with the sitter's name or description. These works consistently revolve around his preferred subject matter: graceful women in moments of quietude or subtle social display. The painting "Apollo and Daphne," mentioned in the source material, suggests an excursion into mythological themes, common within academic training, but seems less typical of his more widely known output focused on contemporary life. These examples collectively paint a picture of an artist skilled in capturing the elegance and intimate moments of Belle Époque femininity.

The Artistic Climate of the Belle Époque

To fully appreciate Ballavoine's position, it's essential to consider the broader artistic context of the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Paris – the era often romanticized as the Belle Époque (roughly 1871-1914). This was a time of relative peace, prosperity, and technological innovation in France, fostering a vibrant cultural scene. The art world was particularly dynamic, characterized by the tension between the established academic tradition represented by the Salon and the rise of successive avant-garde movements.

Ballavoine operated primarily within the Salon system, alongside highly successful academic painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, whose idealized nudes and peasant girls were immensely popular, and Jean-Léon Gérôme, famous for his meticulously detailed historical and Orientalist scenes. Alexandre Cabanel, another pillar of the establishment, achieved enormous success with works like "The Birth of Venus," purchased by Napoleon III. These artists represented the official taste, emphasizing technical perfection, traditional subjects, and a smooth, highly finished style. Ballavoine's 1886 Salon medal places him firmly within this recognized sphere.

Simultaneously, the Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Berthe Morisot, had already challenged the foundations of academic art with their focus on light, color, modern subjects, and looser brushwork. Although initially met with critical hostility, Impressionism gained increasing acceptance during Ballavoine's active years. While Ballavoine did not adopt their revolutionary techniques, the Impressionists' interest in depicting contemporary urban life and leisure may have resonated with his own choice of genre subjects. Renoir's charming portraits of women and children, for instance, share a certain appeal with Ballavoine's work, though Renoir's technique is far looser and more focused on light effects.

Following the Impressionists came the Post-Impressionists, a diverse group including Georges Seurat, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Cézanne. Seurat's development of Pointillism offered a scientific approach to color that stands in stark contrast to Ballavoine's more traditional methods, making the claim of Pointillist influence on Ballavoine intriguing but requiring specific visual evidence. Gauguin's move towards Symbolism and Primitivism represented a radical departure from both academicism and Impressionism.

Other contemporaries relevant to Ballavoine's milieu include painters who navigated a path between academicism and modernism. James Tissot, a Frenchman who spent much of his career in London, painted elegant scenes of contemporary high society with meticulous detail, similar in subject matter to some of Ballavoine's work. The Belgian Alfred Stevens, working in Paris, also gained fame for his depictions of fashionable women in luxurious interiors, executed with exquisite technical skill. These artists, like Ballavoine, catered to the tastes of a wealthy bourgeoisie fascinated by depictions of modern elegance. Even naturalist painters like Jules Bastien-Lepage, while focusing on rural subjects with photographic realism, shared the era's general trend towards contemporary themes over purely historical or mythological ones favored by earlier academic generations. Ballavoine's career unfolded amidst this complex interplay of tradition and innovation.

Interactions with Contemporaries: A Quiet Presence

Despite operating within the bustling Parisian art scene and exhibiting at the Salon alongside many famous names, specific details about Jules Frederic Ballavoine's personal or professional relationships with other artists are notably scarce in historical accounts. The provided source material explicitly states that no information was found regarding collaborations or significant rivalries involving him.

This lack of documentation contrasts with the well-recorded friendships, alliances, and rivalries that characterized other artistic circles of the time. We know, for instance, about the close-knit group of early Impressionists who supported each other and exhibited together, facing shared critical opposition. The intense, sometimes fraught relationships between Post-Impressionist figures like Van Gogh and Gauguin are legendary. Even within the academic sphere, networks of teachers and students, patrons and protégés often left a clearer trace.

The absence of such records for Ballavoine might suggest several possibilities. He may have been a more private individual, less inclined to participate in the café culture or group activities that fostered documented interactions among other artists. Alternatively, his position as a competent but perhaps not leading figure might mean his relationships were simply not considered significant enough for extensive contemporary comment or later historical investigation. His focus seems to have been on consistently producing and exhibiting work that found a market, rather than engaging in the theoretical debates or artistic politics that often generated more historical noise.

Therefore, while we can place Ballavoine geographically and temporally alongside figures ranging from the arch-academic Gérôme to the revolutionary Monet, we cannot, based on current knowledge, detail specific instances of direct influence, collaboration, mentorship (beyond his likely École training), or professional competition. He remains a figure observed primarily through his work and his participation in the official Salon structure, rather than through a rich network of documented personal connections within the art world.

Later Life and Enduring Mysteries

The end of Ballavoine's life is shrouded in the same uncertainty as its beginning. The conflicting death dates – 1901, 1903, or 1914 – make it difficult to pinpoint the exact end of his career or his experiences in the early years of the 20th century. If he lived until 1914, he would have witnessed the emergence of Fauvism and Cubism, radical movements that completely overturned the artistic values his own work largely represented. If he died earlier, around the turn of the century, his career would have concluded firmly within the Belle Époque context.

Regardless of the precise date, his period of greatest activity seems to have been the last quarter of the 19th century and potentially the very beginning of the 20th. This was a time when the artistic landscape was rapidly changing. The Salon system, while still influential, was losing its absolute authority, challenged by independent exhibitions and the rise of private galleries promoting avant-garde art. The tastes of collectors were also diversifying.

The lack of detailed information about his later years, combined with the date discrepancies, contributes to his somewhat elusive status. Did his style evolve in response to the new artistic currents? Did his popularity wane as tastes shifted? Did he continue to exhibit regularly? These questions remain largely unanswered by easily accessible sources. His legacy is thus defined primarily by the body of work produced during his known active period, representing a particular facet of late 19th-century Parisian art that valued charm, elegance, and technical polish.

Market Presence and Collections: A Modest Legacy

Consistent with the general scarcity of detailed information surrounding his life and career, specific data on Jules Frederic Ballavoine's market performance during his lifetime and the current whereabouts of his major works in public or private collections is not readily available through standard art historical databases or the provided source material. We lack records of high-profile commissions, major patrons, or significant acquisitions by leading museums during his era.

However, this does not mean his work is entirely absent from the art market today. Paintings attributed to Jules Frederic Ballavoine appear periodically at auctions in Europe and North America. They typically fall into the category of 19th-century European academic and genre painting. While not commanding the astronomical prices of top-tier Impressionists or renowned academic masters like Bouguereau, his works generally find buyers and achieve respectable sums, reflecting their decorative appeal and competent execution.

The collectors drawn to Ballavoine today likely appreciate the same qualities that made him successful in his own time: the nostalgic charm of the Belle Époque, the graceful depiction of feminine beauty, and the skillful rendering of textures and details. His paintings often appeal to those decorating in traditional styles or those specifically interested in the art of this period that falls outside the main narratives of modernism. While major museums may not prominently feature his work, it is plausible that examples exist in smaller regional museums or remain in private collections passed down through generations or acquired by enthusiasts of 19th-century genre painting. His market presence is thus modest but persistent, indicative of a durable, if secondary, reputation.

Critical Reception: Between Charm and Kitsch

Assessing the critical reception of Jules Frederic Ballavoine's work, both historically and currently, involves navigating terms like "academic," "charming," "poetic," and sometimes, more critically, "kitsch." His success at the Salon, culminating in the 1886 medal, indicates that he achieved positive recognition within the official art establishment of his time. His work evidently appealed to the prevailing tastes that valued technical skill, pleasing subject matter, and a certain degree of idealization. Critics aligned with the Academy likely praised his draftsmanship, compositional abilities, and the refined sentiment of his paintings.

However, from the perspective of the emerging modernist critique, which championed originality, emotional expression, and formal innovation, Ballavoine's work might have been seen as conventional or overly sentimental. The very qualities that made him popular with the Salon jury and bourgeois collectors – the smooth finish, the idealized beauty, the focus on pleasant themes – could be viewed negatively by those who valued the rougher authenticity of Courbet's Realism or the optical experiments of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists.

The label "kitsch," sometimes applied to works like his, refers to art considered overly sentimental, decorative, and lacking in genuine artistic depth, often produced for popular appeal. While perhaps harsh, this term reflects a critical viewpoint that prioritizes avant-garde innovation over traditional craftsmanship and popular charm. Yet, this perspective risks overlooking the genuine skill and artistic intent involved in creating such works. Ballavoine's paintings, while perhaps not groundbreaking, demonstrate considerable technical ability and a consistent aesthetic vision.

Today, art historians tend to view figures like Ballavoine with a more nuanced perspective. Rather than simply dismissing Salon painting as retrograde, there is greater interest in understanding the diversity of artistic production in the 19th century and appreciating the specific qualities and cultural significance of academic and genre painting. Ballavoine's work can be appreciated for its technical accomplishment, its reflection of Belle Époque tastes and ideals of femininity, and its inherent decorative charm, even if it does not occupy a central place in the narrative of art history's major developments.

Conclusion: An Elegant Enigma

Jules Frederic Ballavoine remains a figure of quiet elegance and persistent ambiguity in the annals of French art history. A Parisian through and through, he successfully navigated the competitive art world of the late 19th century, gaining recognition through the official Salon system. His artistic identity is firmly linked to his polished, often idealized depictions of young women, capturing the fashion, leisure, and intimate moments of the Belle Époque with considerable technical skill and a gentle, poetic sensibility.

His style, rooted in academic training, shows an awareness of contemporary life akin to Realism, and perhaps absorbed subtle influences from the Impressionist focus on light and color, though he never fully embraced avant-garde techniques. The conflicting accounts of his birth and death dates add a layer of mystery, complicating a precise understanding of his career arc and his relationship to the rapidly changing artistic currents of his time. Similarly, the scarcity of information regarding his specific teachers, patrons, or interactions with fellow artists leaves gaps in his biography.

While not a revolutionary figure who altered the course of art history like Monet, Degas, or Cézanne, Ballavoine represents a significant segment of artistic practice in his era – the competent, charming Salon painter who catered to and reflected the tastes of a prosperous bourgeoisie. His works, exemplified by titles like "La Séance Interrompue" and "Le Bouquet de Violettes," continue to find appreciation for their craftsmanship and nostalgic allure. He stands as a testament to the diversity of the Parisian art scene, a skilled practitioner whose elegant depictions of femininity offer a valuable, if sometimes overlooked, window onto the visual culture of the Belle Époque.