Auguste Toulmouche stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. A painter celebrated in his time for his exquisitely detailed and charming depictions of Parisian women and their opulent domestic lives, Toulmouche carved a distinct niche for himself within the prevailing Academic tradition. His work, often categorized as genre painting or "costume painting," offers a fascinating window into the aspirations, aesthetics, and social mores of the French bourgeoisie, particularly during the Second Empire and early Third Republic. While the avant-garde movements like Impressionism would eventually overshadow Academic art in historical narratives, Toulmouche's enduring popularity during his lifetime and the continued appreciation for his technical skill and evocative scenes testify to his artistic merit and his keen understanding of his audience.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Nantes

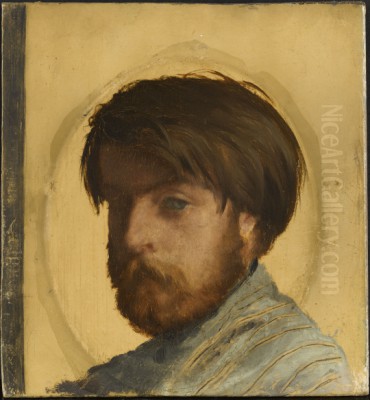

Auguste Toulmouche was born on September 21, 1829, in the bustling port city of Nantes, located in the Brittany region of France. Nantes, with its rich maritime history and vibrant cultural scene, provided an environment where artistic pursuits could be nurtured. His family background appears to have had an artistic inclination; it is believed that his uncle, a sculptor, may have provided some of his earliest exposure to the world of art and perhaps initial encouragement. This familial connection, though not extensively documented, could have played a role in steering young Auguste towards an artistic career.

His formal artistic education began locally. In 1841, at the tender age of twelve, Toulmouche commenced studies in design in his native Nantes. This foundational training would have equipped him with the basic principles of drawing and composition. Two years later, in 1843, he progressed to studying painting under a local portraitist named Biron. While details about Biron are scarce, this apprenticeship would have offered Toulmouche practical experience in oil painting techniques, color theory, and the art of capturing a likeness, skills that would prove invaluable in his later career. These formative years in Nantes laid the groundwork for his artistic development, instilling in him a discipline and a focus on craftsmanship.

Parisian Ambitions and the Atelier of Charles Gleyre

Like many aspiring artists of his generation, Toulmouche recognized that Paris was the undisputed center of the art world. In 1846, at the age of seventeen, he made the pivotal decision to move to the capital to further his artistic training and seek greater opportunities. This move marked a significant step in his journey, immersing him in the competitive and dynamic Parisian art scene.

Upon arriving in Paris, Toulmouche sought out the tutelage of a respected master. He gained entry into the independent studio of Charles Gleyre, a Swiss-born painter who had established himself as an influential teacher in Paris. Gleyre, himself a product of the Academic tradition, was known for his history paintings and mythological scenes, but also for fostering a relatively liberal environment in his studio compared to the more rigid official École des Beaux-Arts. Gleyre's atelier attracted a diverse group of students, some of whom would later become luminaries of the Impressionist movement.

Under Gleyre's guidance, Toulmouche received a thorough grounding in traditional French painting techniques. This would have included rigorous drawing practice from classical plaster casts, life drawing from the nude model, and studies in anatomy and perspective. Gleyre emphasized precision, a refined finish, and a strong compositional structure, all hallmarks of Academic art. It was in this environment that Toulmouche honed his skills, developing the meticulous attention to detail and the polished execution that would characterize his mature style. His time in Gleyre's studio was crucial, not only for the technical skills he acquired but also for the connections he began to make within the Parisian art community.

The Emergence of a Distinctive Style: Academicism and Genre Painting

Auguste Toulmouche's artistic output is firmly rooted in the Academic tradition that dominated French art for much of the 19th century. Academicism, championed by the powerful Académie des Beaux-Arts, prioritized historical and mythological subjects, idealized forms, meticulous finish, and adherence to established artistic conventions. While Toulmouche operated within this framework, he specialized in genre painting – scenes of everyday life – which, though considered lower in the hierarchy of genres than history painting, enjoyed immense popularity with the burgeoning middle and upper classes.

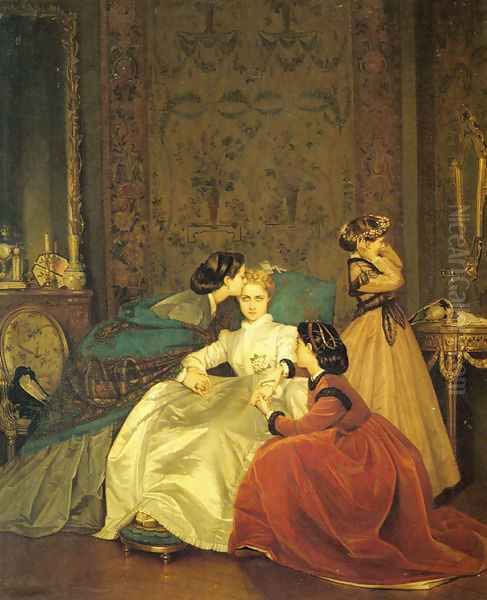

His particular focus became the depiction of elegant women in luxurious domestic interiors. These "costume paintings," as they were sometimes called, celebrated contemporary fashion, refined manners, and the comfortable, often sentimentalized, world of the Parisian bourgeoisie. Toulmouche's canvases are typically filled with rich fabrics, intricate patterns, fashionable attire, and carefully arranged decorative objects, all rendered with painstaking detail. His figures, invariably graceful and poised, are often engaged in quiet, contemplative activities: reading a letter, arranging flowers, lost in thought, or engaged in polite social interaction.

While his style was predominantly realistic in its depiction of material details, there was often an underlying idealism in his portrayal of his subjects and their environments. His women are almost always beautiful, their expressions serene or gently melancholic, and their surroundings impeccably tasteful. This blend of meticulous realism in execution and an idealized vision of contemporary life proved highly appealing to his patrons. Early in his career, around the 1850s, Toulmouche also briefly engaged with the Neo-Greek (Néo-Grec) movement, a sub-genre of Academic art inspired by classical antiquity, often featuring figures in classical or pseudo-classical settings. This influence can be seen in the clarity of form and the somewhat idealized features in some of his earlier works, likely reinforced by his training under Gleyre, who also explored classical themes.

Signature Themes and Narrative Charm

Toulmouche's paintings are more than just pretty pictures; they often possess a subtle narrative quality, inviting the viewer to speculate about the story behind the scene. A recurring theme is that of correspondence – women reading, writing, or receiving letters. These letters, often implied to be love letters or important news, introduce an element of romance, anticipation, or quiet drama. The expressions on the women's faces, their body language, and the surrounding details often provide clues to the emotional content of these missives.

Another common theme is courtship and romantic love, depicted through subtle gestures, shared glances, or symbolic elements within the composition. He also explored moments of quiet domesticity, capturing the intimate and private lives of his female subjects. His paintings often evoke a sense of tranquility, refinement, and emotional sensitivity. The interiors he depicted were not merely backdrops but active participants in the narrative, reflecting the taste, status, and personality of the inhabitants. From plush velvet drapes and ornate gilded mirrors to delicate porcelain and freshly cut flowers, every detail contributed to the overall atmosphere of cultivated elegance.

His meticulous rendering of fabrics – silks, satins, velvets, and lace – was particularly noteworthy. He captured the sheen, texture, and drape of these materials with remarkable skill, making the elaborate costumes a central feature of his art. This focus on fashion resonated deeply with his contemporary audience, who appreciated the depiction of the latest styles and the aspirational lifestyle they represented.

Notable Works and Their Reception

Throughout his career, Auguste Toulmouche produced a significant body of work, with several paintings achieving particular recognition and exemplifying his characteristic style.

One of his early successes was La Fille (The Girl), exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1852. This painting, depicting a young woman in a thoughtful pose, caught the attention of Emperor Napoleon III, who purchased it for his personal collection. This imperial patronage was a significant endorsement and helped to establish Toulmouche's reputation.

L'Attente (The Forbidden Fruit, also sometimes translated as Waiting), painted in 1865, is another well-known work. It depicts a young woman in a sumptuous interior, perhaps awaiting a suitor or contemplating a romantic entanglement. The rich details of her dress and the opulent setting are characteristic of Toulmouche's style. The title itself hints at a narrative of anticipation and perhaps a touch of societal constraint.

La Robe Bleue (The Blue Dress) is a quintessential Toulmouche, showcasing his mastery in rendering luxurious fabrics and capturing a moment of quiet elegance. The vibrant blue of the dress contrasts beautifully with the softer tones of the interior, drawing the viewer's eye to the central figure.

Other notable works include Un Après-midi Tranquille (A Quiet Afternoon), Dans la Bibliothèque (In the Library), Le Billet Doux (The Love Letter), and La Fiancée Hésitante (The Hesitant Fiancée). These titles themselves suggest the narrative and sentimental themes that pervaded his oeuvre. His paintings were regularly exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage.

Salon Success and Official Accolades

Toulmouche's career was marked by consistent success at the Paris Salon. He made his Salon debut in 1848 and continued to exhibit regularly throughout his life. His polished technique, appealing subject matter, and elegant compositions resonated with Salon juries and the public alike.

He received several prestigious awards for his work. In 1852, the same year Napoleon III purchased La Fille, he was awarded a third-class medal at the Salon. This was followed by a second-class medal in 1861. His achievements were also recognized at international exhibitions; he received a bronze medal at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris in 1878.

Perhaps the most significant official recognition of his artistic contributions came in 1870, when he was made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honour. This prestigious award, established by Napoleon Bonaparte, was a mark of high distinction and solidified his status as a respected member of the French artistic establishment. Such accolades not only brought him fame but also ensured a steady stream of commissions and sales, allowing him to enjoy a comfortable and successful career. His patrons included not only Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie but also wealthy industrialists and members of the Parisian haute bourgeoisie.

Connections and Contemporaries: A Network of Artists

Auguste Toulmouche operated within a vibrant and evolving art world, and his career intersected with those of many other notable artists. His most significant connection was arguably with his teacher, Charles Gleyre. Gleyre's studio was a melting pot of talent, and among Toulmouche's fellow students, or those who passed through the studio around the same time, were figures who would go on to define Impressionism, such as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille.

Toulmouche's relationship with Claude Monet was particularly noteworthy. Not only did they share Gleyre as a teacher, but Toulmouche also became related to Monet by marriage. In 1861, Auguste Toulmouche married Marie Lecadre, who was a cousin of Monet. It is documented that Toulmouche played a role in advising the young Monet, encouraging him to join Gleyre's studio in the early 1860s. This guidance, coming from an established and successful Salon painter, would have been significant for Monet at that stage of his career. While their artistic paths diverged dramatically – Toulmouche remaining faithful to Academic principles and Monet pioneering Impressionism – this personal connection is an interesting footnote in art history.

Beyond Gleyre's circle, Toulmouche was a contemporary of other prominent Academic painters who specialized in genre scenes or elegant portrayals of modern life. Alfred Stevens, a Belgian painter active in Paris, was perhaps his closest rival and counterpart, also renowned for his sophisticated depictions of fashionable women in luxurious interiors. Their works share many thematic and stylistic similarities, and both catered to a similar clientele.

Other major figures of the Academic tradition during Toulmouche's era included Jean-Léon Gérôme, a fellow student of Gleyre (though slightly earlier) and a master of historical and Orientalist scenes; William-Adolphe Bouguereau, whose idealized nudes and peasant girls were immensely popular; and Alexandre Cabanel, another favorite of the Salon and official circles. While their subject matter often differed from Toulmouche's domestic scenes, they all represented the dominant artistic paradigm of the time.

Painters like James Tissot, a French artist who later worked in England, also explored themes of modern life and fashion, though often with a slightly different sensibility, sometimes incorporating more overt social commentary or a more narrative complexity. Carolus-Duran (Charles Auguste Émile Durand) was another contemporary, known for his society portraits and his influence as a teacher. The broader artistic milieu also included figures like Édouard Tourouze, a history and landscape painter, and Charles Émile Vacher de Tournemine, known for his genre scenes. Jean-Baptiste Jules Trayer was another portraitist and genre painter of the period. Toulmouche's success must be seen in the context of this competitive environment, where many artists vied for Salon recognition and patronage.

Critical Reception: Admiration and Detraction

During his lifetime, Auguste Toulmouche enjoyed considerable popularity and critical acclaim, particularly from conservative critics and the art-buying public. His technical proficiency, the charm of his subjects, and the aspirational quality of his scenes were widely admired. His paintings were seen as epitomes of good taste and refinement, perfectly suited to the drawing-rooms of the wealthy. The meticulous detail and polished finish were appreciated as hallmarks of skilled craftsmanship.

However, as the 19th century progressed and new artistic ideas began to challenge the dominance of Academicism, Toulmouche's work, like that of many of his Academic contemporaries, also faced criticism, particularly from proponents of Realism and, later, Impressionism. The writer and art critic Émile Zola, a staunch champion of Manet and the Impressionists, famously dismissed Toulmouche's idealized female figures as "delicious dolls" ("délicieuses poupées"). Zola and other progressive critics found such art to be superficial, overly sentimental, and lacking in genuine engagement with the realities of modern life. They favored art that was more challenging, innovative, and less concerned with conventional notions of beauty and propriety.

This divergence in critical opinion reflects the broader artistic debates of the era – the clash between tradition and modernity, between the established Salon system and the emerging avant-garde. While Toulmouche's art may not have possessed the revolutionary fervor of Courbet's Realism or the groundbreaking optical experiments of the Impressionists, it fulfilled a different, but equally valid, artistic and social function for its time. It provided pleasure, beauty, and a reflection of the idealized self-image of a significant segment of society.

Later Life, Legacy, and Enduring Appeal

Auguste Toulmouche continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life, maintaining his characteristic style and subject matter. He passed away in Paris on October 16, 1890, at the age of 61, leaving behind a substantial body of work.

In the decades following his death, as Impressionism and subsequent modernist movements came to dominate art historical narratives, Academic painters like Toulmouche were often relegated to the footnotes of art history, their work sometimes dismissed as merely decorative or anachronistic. However, in more recent times, there has been a renewed scholarly and public interest in 19th-century Academic art. Art historians have begun to re-evaluate these artists on their own terms, recognizing their technical skill, their cultural significance, and the specific aesthetic values they represented.

Today, Auguste Toulmouche's paintings are held in numerous public and private collections around the world, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nantes, and various museums in the United States, where his work was particularly popular among collectors. His paintings continue to be admired for their exquisite craftsmanship, their evocative portrayal of a bygone era, and their sheer visual charm. They offer valuable insights into the social history, fashion, and interior design of 19th-century Paris. For those interested in the art of the Second Empire, the intricacies of Academic painting, or the representation of women in art, Toulmouche's work remains a source of fascination and delight. He stands as a testament to an artist who, by understanding and catering to the tastes of his time, achieved remarkable success and left behind a legacy of elegance and refined beauty.