Hans Burgkmair the Elder stands as one of the most significant and innovative artists of the German Renaissance. Active as both a painter and a prolific woodcut printmaker, he played a crucial role in transmitting Italian Renaissance ideals into the visual language of Northern Europe. Born in the imperial city of Augsburg in 1473 and dying there in 1531, Burgkmair's career coincided with a period of immense artistic, religious, and intellectual ferment. His extensive oeuvre, characterized by a vibrant synthesis of German tradition and Italianate humanism, left an indelible mark on the art of his time and continues to be a subject of scholarly interest.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Hans Burgkmair was born into an artistic family in Augsburg. His father, Thoman Burgkmair (c. 1444–1523), was a painter, providing young Hans with his initial exposure to the craft. Augsburg, at this time, was a wealthy and cosmopolitan Free Imperial City, a major trading hub with strong connections to Italy, making it a fertile ground for artistic exchange and innovation. This environment undoubtedly shaped Burgkmair's outlook and ambitions.

Seeking more advanced training, Burgkmair traveled to Colmar in Alsace around 1488. There, he became a pupil of the preeminent painter and engraver Martin Schongauer (c. 1448–1491). Schongauer was a master of late Gothic naturalism and refined engraving techniques, and his workshop was a leading center for artistic training in the Upper Rhine region. Although Schongauer died relatively soon after Burgkmair's arrival, the experience would have been formative, instilling in the young artist a strong foundation in draftsmanship and the graphic arts. Artists like Matthias Grünewald also likely passed through Schongauer's circle or were deeply influenced by his work, highlighting the importance of this master.

Italian Journeys and Renaissance Awakening

A pivotal period in Burgkmair's development was his journey, or possibly journeys, to Italy. While the exact dates and duration of his Italian sojourns are not definitively documented, the profound impact of Italian Renaissance art is undeniable in his subsequent work. It is generally believed he traveled to Italy sometime in the 1490s, possibly before establishing himself independently, and perhaps again around 1507.

During his time in Italy, Burgkmair would have encountered the revolutionary artistic developments firsthand. He was particularly influenced by the Venetian school, known for its rich color, atmospheric effects, and grand narrative compositions. The works of artists such as Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430–1516) and Vittore Carpaccio (c. 1460–1526) likely made a strong impression, with their sophisticated use of light, perspective, and humanistic portrayal of figures. He absorbed the classical motifs, the interest in human anatomy, and the principles of harmonious composition that were hallmarks of the Italian Renaissance. This exposure fundamentally transformed his artistic vision, moving him beyond the purely Gothic idiom.

Upon his return to Augsburg, Burgkmair was equipped with a new artistic vocabulary. He became a master in the Augsburg painters' guild in 1498, signifying his official status as an independent artist. He married Anna Allerley, and their son, Hans Burgkmair the Younger (1500–1562), would also become an artist, continuing the family tradition.

Master of the Woodcut: Innovation and Imperial Patronage

While a gifted painter, Hans Burgkmair the Elder achieved perhaps his most widespread fame and influence through his prodigious output of woodcuts, estimated to be around 700. He was a key figure in the flourishing of German printmaking, alongside contemporaries like Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553). Burgkmair, however, carved a unique niche for himself.

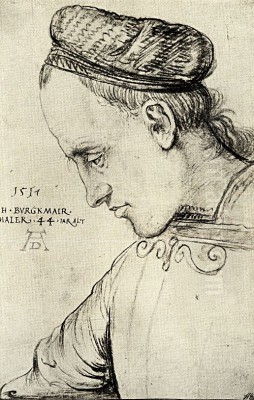

One of his most significant contributions was his pioneering work in chiaroscuro woodcuts. This technique involved using multiple blocks, typically a key block for the lines and one or more tone blocks inked in different colors or shades, to create effects of light, shadow, and volume, mimicking the appearance of wash drawings. His Emperor Maximilian I on Horseback (1508) and St. George and the Dragon (1508) are early and impressive examples of this technique, demonstrating a sophisticated understanding of tonal values. The Portrait of Johann Paumgartner (1512) is another celebrated chiaroscuro woodcut, showcasing his ability to capture individual likeness with graphic power.

Burgkmair's skill attracted the attention of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, who became a major patron. The emperor, a keen propagandist, utilized the relatively new medium of printmaking to promote his image and legacy. Burgkmair was a leading contributor to several of Maximilian's ambitious print projects. The most famous of these is The Triumph of Maximilian I (begun c. 1512, largely completed by 1519, published 1526), a monumental series of 137 woodcuts depicting a vast triumphal procession. Burgkmair designed the largest portion of these prints, working alongside other prominent artists such as Albrecht Altdorfer (c. 1480–1538), Hans Schäufelein (c. 1480–c. 1540), Leonhard Beck (c. 1480–1542), and Dürer himself. Burgkmair's contributions are noted for their lively figures, rich ornamentation, and dynamic compositions, effectively conveying the splendor and power of the Emperor.

He also provided numerous woodcut illustrations for other imperial projects, including the chivalric romance Teuerdank (published 1517), which allegorically recounted Maximilian's journey to marry Mary of Burgundy, and the Weisskunig (The White King), an allegorical autobiography of the Emperor, for which Burgkmair created many designs (though it was not published until much later). These commissions solidified his reputation as one of the leading graphic artists in the German-speaking lands.

The Painter: Altarpieces, Portraits, and Frescoes

Alongside his printmaking activities, Hans Burgkmair maintained a successful painting practice. His painted works, like his prints, demonstrate a fusion of German expressive intensity with Italianate grace and monumentality.

He produced several significant altarpieces. The St. John Altarpiece (1518), created for the Dominican church in Augsburg and now in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich, showcases his mature style. Its central panel, St. John on Patmos, is a powerful and visionary depiction, with a dramatic landscape and a monumental figure of the evangelist. The wings feature scenes from the lives of saints, rendered with rich color and attention to narrative detail. Another important work is the Crucifixion Altarpiece (1519), also in Munich, which combines emotional intensity with a balanced, Renaissance-inspired composition. His Adoration of the Shepherds (Alte Pinakothek, Munich) and Seven Holy Helpers (Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe) further exemplify his skill in religious painting.

Burgkmair was also an accomplished portraitist. His double portrait, The Painter Hans Burgkmair and his Wife Anna (1529, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), is a remarkable work, offering an intimate yet dignified portrayal of the artist and his spouse. It reflects the growing self-awareness of artists during the Renaissance. Another notable portrait is A Young Man (Jicus der jungen Mann), also in Vienna, which captures the subject's personality with sensitivity.

He was involved in fresco projects as well. Notably, he collaborated with Hans Holbein the Elder (c. 1460–1524), another leading Augsburg painter and father of the more famous Hans Holbein the Younger, on a cycle of paintings depicting the seven basilicas of Rome for the Dominican convent of St. Catherine in Augsburg around 1501-1504. This collaboration highlights the vibrant artistic community in Augsburg, where artists often worked together on large-scale commissions. Other Augsburg artists of the period included Jörg Breu the Elder (c. 1475/80–1537), who also contributed to the artistic vibrancy of the city.

Thematic Diversity and Intellectual Engagement

Burgkmair's oeuvre is notable for its thematic diversity. Beyond traditional religious subjects and portraiture, he explored historical, mythological, and even ethnographical themes, reflecting the expanding intellectual horizons of the Renaissance.

His interest in history is evident in works like The Battle of Cannae (1529, Alte Pinakothek, Munich), part of a series of historical battle scenes commissioned by Duke Wilhelm IV of Bavaria. Burgkmair meticulously researched Roman armor and military formations, demonstrating a humanist concern for historical accuracy, a trait shared with artists like Andrea Mantegna in Italy.

Perhaps most strikingly, Burgkmair produced a series of woodcuts in 1508 titled The Peoples of Africa and India (also known as The King of Cochin series). These prints, based on accounts from Balthasar Springer's voyage to India, are among the earliest European depictions of people from these distant lands. While filtered through a European lens and containing fantastical elements, they represent a significant early attempt at ethnographical representation and reflect the era's burgeoning interest in the wider world, spurred by voyages of discovery.

He also created works with moral and allegorical content, such as the woodcut series Three Good Jewish Women and Three Good Christians, catering to the didactic tastes of the time. An interesting anecdotal piece is a woodcut from 1516, commissioned to record the unusual birth of twins, an event also documented by a local artist named Matthäysen. This demonstrates the artist's role in chronicling contemporary events.

His friendship with the Augsburg humanist Conrad Peutinger (1465–1547), a renowned scholar, diplomat, and antiquarian, further underscores Burgkmair's engagement with the intellectual currents of his time. Peutinger was a key figure in Augsburg's cultural life and likely facilitated Burgkmair's access to classical texts and ideas, influencing the content and style of his work.

Artistic Style and Technical Prowess

Hans Burgkmair's artistic style is a compelling synthesis of Northern European traditions and Italian Renaissance innovations. From his German heritage, he retained a strong sense of line, a penchant for expressive detail, and a certain emotional directness. From Italy, he adopted a more monumental conception of form, an understanding of classical proportion and perspective, and a richer, warmer color palette, particularly evident in his paintings.

His compositions are often complex and dynamic, filled with figures and decorative elements, yet generally maintain a sense of clarity and balance. He demonstrated a keen interest in rendering textures, from shimmering silks to polished armor, and his landscapes, while often idealized, provide atmospheric settings for his narratives. In his paintings, such as the Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine, one can see a Northern figural type placed within a landscape that evokes the compositional strategies of Venetian artists like Giorgione (c. 1477/8–1510), albeit with a distinctly German sensibility.

In his woodcuts, Burgkmair displayed exceptional technical skill. He understood how to translate complex forms and tonal variations into the demanding medium of woodcut. His lines are vigorous and expressive, and his pioneering use of chiaroscuro added a new dimension of pictorial richness to printmaking, influencing subsequent generations of printmakers. He was not merely a designer who handed off his drawings to block cutters; he was deeply involved in the technical possibilities of the medium.

Later Life, Family, and Artistic Legacy

Hans Burgkmair the Elder remained active in Augsburg until his death in 1531. He ran a successful workshop and was a respected figure in the city's artistic and civic life. His son, Hans Burgkmair the Younger, followed in his footsteps as a painter and etcher, and they collaborated on projects such as the Turnierbuch (Tournament Book), a series of woodcuts depicting jousting scenes.

Burgkmair's influence was significant. He was a key conduit for Italian Renaissance ideas into Germany, adapting them to a Northern European context. His innovations in woodcut, particularly chiaroscuro, had a lasting impact on the development of printmaking. His work for Emperor Maximilian I helped to define the visual culture of the imperial court and disseminated his style widely. He influenced numerous artists, including, to some extent, the younger generation like Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8–1543), especially in the realm of decorative design and print.

Modern Research and Appreciation

For a period, Hans Burgkmair the Elder was somewhat overshadowed by his more famous contemporary, Albrecht Dürer. However, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized Burgkmair's unique contributions and his pivotal role in the German Renaissance. Exhibitions of his work and scholarly publications have shed new light on his diverse oeuvre and his artistic significance.

A notable example of this renewed interest was an international symposium held in 2014, "Hans Burgkmair and his Impact," which resulted in the publication of the volume Hans Burgkmair: Impact and Works. Such initiatives have helped to fill gaps in the understanding of German Renaissance art and to re-evaluate Burgkmair's position within it. His works are now prominently displayed in major museums worldwide, including the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, the Albertina in Vienna, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, among others.

His legacy is multifaceted: as an innovator in printmaking, a skilled painter who masterfully blended Northern and Southern European artistic currents, a chronicler of his time, and an artist who engaged with the burgeoning humanist culture of the Renaissance.

Conclusion

Hans Burgkmair the Elder was a transformative figure in German art. His willingness to embrace and adapt Italian Renaissance principles, combined with his mastery of both painting and the rapidly evolving medium of woodcut, set him apart. Through his prolific output, particularly his widely circulated prints and his contributions to Emperor Maximilian's grand projects, he played a vital role in shaping the visual landscape of the Northern Renaissance. His art, rich in color, dynamic in composition, and diverse in subject matter, continues to captivate and inform, securing his place as a leading master of his era. His ability to synthesize diverse influences while forging a distinct personal style marks him as a true innovator and a cornerstone of Renaissance art north of the Alps.